Miguel Boyer (5 February 1939 – 29 September 2014) was a Spanish economist and politician, who served as minister of economy, treasury and commerce from 1982 to 1985.

Miguel Boyer | |

|---|---|

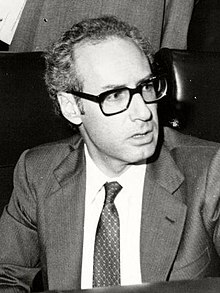

Miguel Boyer in 1983 | |

| Minister of Economy, Treasury and Commerce | |

| In office 1 December 1982 – 6 July 1985 | |

| Prime Minister | Felipe González |

| Preceded by | Jaime García Añoveros |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Solchaga |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Miguel Boyer Salvador 5 February 1939 St. Jean de Luz, France |

| Died | 29 September 2014 (aged 75) Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Political party | Socialist Party |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Complutense University of Madrid |

Early life and education

editBoyer was born in St. Jean de Luz, France, on 5 February 1939.[1] He was a graduate of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid where he studied economics.[2] He also received a degree in physics from the same university.[3]

Career

editBoyer worked at different banks and institutions.[4] He served as the director of planning for the Unión Explosivos Río Tinto and later as a senior economist at the Bank of Spain.[5][6] He became the deputy director of the national industrial institute and then its director in 1974.[1] Next he worked at the state-owned hydrocarbons institute.[5] He was one of the Ibercorp shareholders.[7]

Boyer joined the Socialist Party as part of its social democrat wing in 1960.[1][8] He helped Felipe González to form a faction in the party in the mid-1970s.[9] Boyer was a member of the Congress of Deputies, representing Jaén Province, and economic spokesperson of the party.[10] He and Carlos Solchaga were the architects of the party's economy policy.[4]

Boyer was appointed minister of economy, treasury and commerce to the first cabinet of Felipe González on 2 December 1982.[4][11] In 1985, he developed a tax act that enabled people to avoid tax on saving interest if they invested in insurance accounts.[12] During his term he was regarded as the most powerful member of the cabinet.[13][14] However, in a cabinet reshuffle in July 1985 Boyer was removed from office and was succeeded by Carlos Solchaga in the post.[13][15] It was speculated that Boyer was forced to resign due to his clash with Deputy Prime Minister Alfonso Guerra.[13][14] In addition, Boyer attempted to increase his power in the cabinet and demanded to assume the post of second vice prime minister, also leading to his forced resignation.[16]

Shortly after leaving office Boyer was named as the chief executive of the Banco Exterior de Espana and next of the investment company, Cartera Central.[17] In 1986, he was named as a member of the Abragam committee that oversaw the future structure of the CERN.[18][19] Until 1999 he served as a senior manager at the Spanish construction group FCC.[20] From July 1999 to January 2005, he was the chairman of CLH, a Spanish fuel distribution company.[20] In May 2010, Boyer was appointed board member to the Hispania Racing Team.[21] He also assumed the post of finance director and advisor to the team.[22] On 20 May 2010, he was also named as the independent member of the board of directors of Red Electrica Corporacion SA.[3] In addition, he served as the head of Urbis.[23]

Controversy

editIn February 1992, Boyer and Mariano Rubio, former governor of the Bank of Spain, were accused of fraud and share-price manipulation in relation to the Ibercorp.[7][24] Boyer was not sentenced, but Rubio was sentenced to jail.[24]

Views

editIn the 1970s, Boyer supported self-managing socialism.[25] However, later he became known for his orthodox, moderate and pragmatic approach to economy.[26] Despite being a member of the socialist government, he adopted neo-liberal views of economy when he was minister.[16] In addition, he and his successor Carlos Solchaga did not fit into the party's projected socialist mould.[27] They both implemented economic policies based the orthodox liberal ideas, and the social outcomes of these policies were largely neglected.[28] Their priority was to reduce inflation, using steps to control the money supply, which reinforced the high levels of interest and a strong currency.[27] Although Boyer's policy decreased the rate of inflation and government spending, Spain experienced the Europe's highest unemployment rate at about 20%.[29] Boyer also encouraged the economic integration of Spain into the European Union.[30]

Personal life and death

editBoyer divorced his first wife, gynecologist Elena Arnedo, to wed a socialite, Isabel Preysler, in 1987.[31] Boyer's first wife, Elena Arnedo, was the cousin of Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo.[5] Isabel Preysler was the former spouse of the singer Julio Iglesias and Carlos Falcó, 5th Marquess of Griñón.[32] They had a daughter, Ana Boyer.[31] Boyer had also a son and a daughter with his first wife.[33][34]

Boyer died of a pulmonary embolism after being admitted to the Ruber International Hospital in Madrid on 29 September 2014.[35][36] He was 75.[36]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Eamonn J. Rodgers; Valerie Rodgers, eds. (1999). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Spanish Culture. London; New York: Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-415-13187-2.

- ^ "José Luis Sampedro: Economist who became an inspiration for Spain's anti-austerity movement". The Independent. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Red Electrica Corporacion SA (REE.MC)". Reuters. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Omar G. Encarnación (2008). Spanish Politics: Democracy After Dictatorship. Cambridge: Polity. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-7456-3992-5.

- ^ a b c Richard Wigg (February 1983). "Socialism in Spain: A Pragmatic Start". The World Today. 39 (2): 63. JSTOR 40395475.

- ^ "Spain's pragmatic socialism finds management types in key posts". The Christian Science Monitor. 14 October 1983. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Spain's Insiders in Insider Scandal". The New York Times. 23 May 1992. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ James M. Markham (1 December 1982). "Spain's new leader outlines cautious plans to parliament". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Dennis Kavanagh, ed. (1998). "González Márquez, Felipe". A Dictionary of Political Biography. Who's Who in Twentieth-Century World Politics. Oxford: OUP. p. 191. ISBN 978-0192800350.

- ^ "Euphoria turns to moderation as Spain's Socialists face reality of power". The Christian Science Monitor. 1 November 1982. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Francisco Comín (2007). "Reaching a political consensus: The Moncloa pacts, joining the European Union and the rest of the journey". In Jorge Martínez-Vázquez; José Félix Sanz Sanz (eds.). Fiscal Reform in Spain: Accomplishments and Challenges. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-78254-271-1.

- ^ John Gibbons (1999). Spanish Politics Today. Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7190-4946-0.

- ^ a b c "Spanish Premier Airs Out Cabinet, Replaces 6". Chicago Tribune. Madrid. 5 July 1985. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b Edward Schumacher (5 July 1985). "Spain's leader drops top aides in a big shuffle". The New York Times.

- ^ John Gillingham (2003). European Integration, 1950-2003: Superstate Or New Market Economy?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-521-01262-1.

- ^ a b Otto Holman (2012). Integrating Southern Europe: EC Expansion and the Transnationalization of Spain. London; New York: Routledge. p. 1965. ISBN 978-1-134-80356-9.

- ^ Paul Heywood (1 October 1995). "Sleaze in Spain". Parliamentary Affairs. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Herwig Schopper; James Gillie (2024). Herwig Schopper Scientist and Diplomat in a Changing World. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 150–151. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-51042-7_7. ISBN 978-3-031-51041-0.

- ^ Herwig F. Schopper (2009). Lep: The Lord of the Collider Rings at CERN 1980-2000: The Making, Operation and Legacy of the World's Largest Scientific Instrument. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-540-89301-1.

- ^ a b "Repsol YPF to replace Boyer at helm of CLH". El Pais. 13 January 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Hispania forms new board of directors". GP Update. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Alex Duff (27 May 2011). "Formula 1 Team Uses 175-Mile-Per-Hour Rolling Billboard to Find Sponsors". Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Miguel Boyer leaves the ICU and evolves "very satisfactory"". Nasdaq Report News. 11 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ a b Hayley Rabanal (2011). Belén Gopegui: The Pursuit of Solidarity in Post-transition Spain. Woodbridge: Tamesis. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-85566-233-9.

- ^ Juliá Santos (1990). "The ideological conversion of the leaders of the PSOE, 1976-1979". In Lannon Frances; Preston Paul (eds.). Élites and power in twentieth-century Spain. Essays in honour of Sir Raymond Carr. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198228806.

- ^ John Williamson (1994). The Political Economy of Policy Reform. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-88132-195-1.

- ^ a b Jose Amodia (1994). "A victory against all the odds: The declining fortunes of the Spanish Pocialist Party". In Richard Gillespie (ed.). Mediterranean Politics. London: Pinter Publishers Ltd. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8386-3609-1.

- ^ Richard Gillespie (1992). "Factionalism in the Spanish Socialist Party" (PDF). Working Papers Barcelona (59). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Spain's Finance Minister Quits Amid Major Cabinet Reshuffle". Los Angeles Times. 5 July 1985. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ Richard Gillespie; Fernando Rodrigo; Jonathan Story, eds. (1995). "Western alignment: Spain's security policy". Democratic Spain: Reshaping External Relations in a Changing World. London: Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-415-11325-0.

- ^ a b Robby Tantingco (10 December 2012). "The Kapampangan girl Julio Iglesias loved before". Sun Star. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "The Beautiful Women of the Philippines". Angelfire. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Ex-economy minister Miguel Boyer dies in hospital". Gnomes. 29 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ "Así ha quedado repartida la herencia de Miguel Boyer: su hija Laura ha renunciado a su parte". El Mundo (in Spanish). 27 October 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Mor als 75 anys l'exministre socialista Miguel Boyer per una embòlia pulmonar". 324 (in Spanish). 29 September 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Miguel Boyer Dies at 75 Years Old in Madrid". Getty Images. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

External links

edit- Media related to Miguel Boyer at Wikimedia Commons