James Michael Curtis (March 27, 1943 – April 20, 2020), nicknamed "Mad Dog" or "the Animal," was an American professional football player for the Baltimore Colts, Seattle Seahawks, and Washington Redskins. He played a total of 14 seasons in the National Football League (NFL), running from 1965 to 1978.

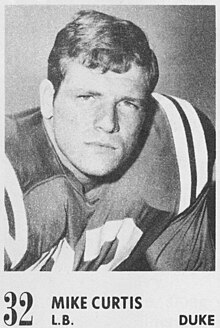

Curtis in 1970 | |||||||||||||

| No. 32 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position: | Linebacker | ||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||

| Born: | March 27, 1943 Rockville, Maryland, U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Died: | April 20, 2020 (aged 77) St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) | ||||||||||||

| Weight: | 232 lb (105 kg) | ||||||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||||||

| High school: | Richard Montgomery (Rockville, Maryland) | ||||||||||||

| College: | Duke | ||||||||||||

| NFL draft: | 1965 / round: 1 / pick: 14 | ||||||||||||

| AFL draft: | 1965 / round: 3 / pick: 21 | ||||||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Curtis was a four-time Pro Bowler, named to the squad in 1968, 1970, 1971, and 1974. Although sacks were not official during the time he played, Curtis was a good blitzer, recording 22½ sacks, and pass defender, picking off 25 passes. He was named the AFC Defensive Player of the Year in 1970 by a panel of 101 sportswriters.

Early life

editMike Curtis was born March 27, 1943, in Washington D. C. and grew up in Rockville, Maryland. He attended Richard Montgomery High School in Rockville, where he played football, tipping the scales at 195 pounds and playing fullback as a junior in 1959. He was named All Metro by the Washington Post in 1960.[1]

College career

editCurtis was offered a number of athletic scholarships to play college football, ultimately deciding to accept the offer of Duke University, located in Durham, North Carolina. He later recalled that he had enormous trouble with the adjustment, unhappy and homesick, and nearly flunking out of school due to a failure to apply himself academically.[2] Moreover, he was injured playing freshman football, hurting his knee and breaking a bone in his hand.[2]

A report card filled with three F grades, two Ds, and an A in physical education had an invigorating effect, Curtis noted in his 1972 memoir: "It was one of the best things that ever happened to me. I realized then that the most important thing in my life was to graduate from college. Nothing else, including football, was important."[3]

Curtis declined to fill his spring schedule with easy physical education classes, as suggested by the Duke athletic department, instead taking classes that put him on a degree track and attending summer school after his freshman year.[4] He changed his academic major from business to history to ease his path in the classroom.[4]

On the football field, Curtis played both sides of the ball — fullback on offense and middle linebacker on defense.[4] He was First Team All ACC twice, as a fullback and a linebacker.[5]

He suffered four knee injuries during the course of his college football career,[6] but became a member of Duke’s Athletic Hall of Fame, and was selected an All ACC Academic in 1963, an Academic All America, and an honorable mention All American in 1964.[5][1]

Professional career

editCurtis was drafted in the first round of the 1965 NFL draft by the Baltimore Colts, 14th overall,[1] originally slated as fullback. He was also drafted in the third round of the 1965 AFL Draft by the Kansas City Chiefs. Players had significant financial leverage in this period, with two teams competing for their services, and Curtis received a healthy two-year contract to play for the Colts. The deal paid him $15,000 for the 1965 season and $17,000 for 1966, plus a signing bonus of $22,000 — a total of $54,000 (about $535,000 in 2024) for two years.[7]

During his rookie season with the Colts, Curtis was listed third on the depth chart at fullback, playing behind Tony Lorick and Jerry Hill.[8] He was moved to outside linebacker by future hall of fame head coach Don Shula in 1966.[8][9] After being named first team All Pro in 1968[10] — a year in which the Colts led the NFL in scoring defense en route to winning the NFL Championship — he was moved to middle linebacker in 1969 where he was named second team All Pro behind Dick Butkus,[10] and he would be selected to the Pro Bowl for each of the next three years.[11] In the 1968 playoffs against Minnesota, he returned a fumble 60 yards for a touchdown.[10]

Curtis, Ray May, and Hall of Famer Ted "the Mad Stork" Hendricks formed a potent linebacking corps from 1970 to 1973,[1] helping the team to victory in January 1971 in Super Bowl V against the Dallas Cowboys. That 1970 season was one of Curtis' finest, in which he had five interceptions, including a key pick that set up the Colts' game-winning field goal in the championship game.[12] Many have said he should have been the Super Bowl V MVP for his last meeting interception, but the voting was already in on that award by that point in the game.[9] Future NFL hall of famer Chuck Howley instead won that accolade, still the only player from a losing team in the Super Bowl to be named MVP.[13]

Curtis was named the Colts' Most Valuable Player in 1974, and honor he twice received from his Colt teammates.[14][10] He was a team captain[10] for most of his Baltimore career. He was selected to the Pro Bowl four times between 1968 and 1974 — all years in which he wore the blue-and-white uniform of the Colts. He was AFC Defensive Player of the Year in 1970. He was uniquely named All-Pro at both middle linebacker and outside linebacker during his Colts career.[9]

Curtis' 1975 season was cut short on November 12 when he opted for surgery to repair cartilage in his left knee, which he had injured in a preseason game in early September.[15] Despite the objections of head coach Ted Marchibroda,[16] Curtis was left unprotected for the 1976 NFL Expansion Draft due to a personality conflict with general manager Joe Thomas. "I heard indirectly that I was in the expansion draft because Joe Thomas hated my guts," he said. "Thomas could have had a first-round draft choice or better for me if he had wanted it."[17]

Curtis was selected by the Seattle Seahawks on March 30, 1976.[18] He started all 14 regular-season games during the Seahawks' inaugural campaign and was the team's first defensive captain.[19] The Seahawks returned him to right outside linebacker for the season and Curtis responded like a professional, finishing the year second on the team in tackles, with 107.[19]

After being supplanted by Ken Geddes on the depth chart prior to the start of the 1977 season, he was waived by the Seahawks on September 6. He signed with the Washington Redskins three days later.[20] He started 11 games in place of the injured Chris Hanburger in 1977, but only two of the 13 contests in which he played the following year. His intention to retire after the 1979 season was expedited before the campaign began when he was released by the Redskins on August 7.[21]

Curtis finished his career with 25 interceptions, 22 quarterback sacks, 10 fumble recoveries and scored four touchdowns; and was one of the most feared players of his era.[9][10] Green Bay Packers hall of fame quarterback Bart Starr said of Curtis, that if the feared hall of fame linebacker Dick Butkus was scary, Curtis was scarier. As a rookie on the Colts, he was even willing to confront team legend Johnny Unitas over a perceived lack of respect.[9]

Life after football

editCurtis married and had three children—two boys and a girl.[1]

A self-described "loner" who preferred his own company or that of his family, Curtis had a 44-acre farm near Leesburg, Virginia, purchased with his winner’s share of the proceeds of Super Bowl III.[22] He also owned a house in Rockville, Maryland, and invested a good part of his football income buying and selling real estate.[23]

Death and legacy

editCurtis struggled with memory loss late in life,[11] a condition associated with damage due to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease caused by repeated head injuries. He died peacefully, surrounded by loved ones on April 20, 2020, in St. Petersburg, Florida.[11] His family donated his brain to the Brain Injury Research Institute for examination in association with their ongoing study of CTE.[11]

Curtis is remembered for his role as a losing member of the Colts team in Super Bowl III, still regarded as one of the greatest upsets in NFL history. During the 1971 season, still active with the Colts, Curtis wrote a memoir of his career to date, Keep Off My Turf. In it he stated that the New York Jets, who upset the Colts that day, were lucky:

"Our team was twice as good as the Jets. Twice as good. There wasn't any comparison between the two teams. If [Jimmy] Orr and [Tom] Mitchell had been able to catch those two passes for touchdowns early in the game, it would have been a romp. We've beaten them every time we've played them since. That says something. But it still can't erase that day in the Super Bowl."[24]

He is also remembered more positively for his game-changing interception and return with little more than one minute left in Super Bowl V, setting up Colts kicker Jim O'Brien for the game-winning field goal.[11]

His friend and teammate, Colts center Bill Curry recalled of Curtis: "You really missed the thrill of getting to see a great NFL linebacker if you didn't see him play.... It was like watching the guy with the muscularity of a defensive tackle who could run like a corner. It was incredible to see him run people down. How could he do that? But he did it every day."[11] Curtis once ran the forty-yard dash in 4.3 seconds.[9]

There have been many who have asserted the position that Curtis should be in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, such as hall of famers Ted Hendricks, Joe Namath, Roger Staubach, Don Shula and others like Larry Brown.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Walker, Childs (April 20, 2020). "Mike Curtis, fiery Pro Bowl linebacker with Baltimore Colts, dies at 77". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved November 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Mike Curtis with Bill Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1972; pp. 42–43.

- ^ Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, p. 46.

- ^ a b "Mike Curtis (1981) - Duke Athletics Hall of Fame". Duke University. Retrieved November 3, 2024.

- ^ Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, p. 48.

- ^ Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, p. 53.

- ^ a b Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g Preston, Mike (October 25, 2019). "Former Baltimore Colts great Mike Curtis might finally get his much-deserved Hall of Fame nod". Baltimore Sun.

- ^ a b c d e f Gosselin, Rick (June 24, 2022). "State Your Case: Mike Curtis". Rick Gosselin. Retrieved November 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Childs Walker, ""A Player's Player": Curtis, A Four-time Pro Bowl Colts Linebacker, Dies at 77," Baltimore Sun, April 21, 2020, pp. D1–D2.

- ^ Dave Anderson, "Interception by Curtis Turning Point: Colts," New York Times, January 18, 1971.

- ^ "Chuck Howley of the Cowboys is the only Super Bowl MVP from a losing team. Now he's a Hall of Famer". AP News. August 1, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2024.

- ^ Barry Jones (ed.), ’75 Colts Media Guide. Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Colts Football Club, 1975; p. 23.

- ^ Deane McGowen, "People in Sports," New York Times, November 13, 1975.

- ^ Associated Press, "Winning Didn't Cure All the Ills in Baltimore," January 22, 1977.

- ^ "Feathering A Nest Of Seahawks," Sports Illustrated, May 24, 1976.

- ^ "N.F.L. Veterans Drafted," The New York Times, Wednesday, March 31, 1976. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Bob Condotta, "Mike Curtis, First Defensive Captain for Seattle Seahawks, Dies at Age 77," Seattle Times, April 20, 2020.

- ^ Leonard Shapiro, "Redskins Put Curtis On Roster," The Washington Post, September 10, 1977. Retrieved December 9, 2018

- ^ Associated Press, "Mike Curtis, 36, Cut by Redskins," New York Times, August 7, 1979.

- ^ Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Curtis and Gilbert, Keep Off My Turf, pp. 74–75.