Mildred Delores Loving (née Jeter; July 22, 1939 – May 2, 2008) and Richard Perry Loving (October 29, 1933 – June 29, 1975) were an American married couple who were the plaintiffs in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia (1967). Their marriage has been the subject of three movies, including the 2016 drama Loving, and several songs.[1][2] The Lovings were criminally charged with interracial marriage under a Virginia statute banning such marriages, and were forced to leave the state to avoid being jailed. They moved to Washington, D.C., but wanted to return to their home town. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), they filed suit to overturn the law. In 1967, the Supreme Court ruled in their favor, striking down the Virginia statute and all state anti-miscegenation laws as unconstitutional, for violating due process and equal protection of the law under the Fourteenth Amendment.[3] On June 29, 1975, a drunk driver struck the Lovings' car in Caroline County, Virginia. Richard was killed in the crash, at the age of 41. Mildred lost her right eye.[4]

Mildred and Richard Loving | |

|---|---|

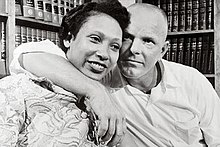

Mildred and Richard Loving in 1967 | |

| Born | Mildred Mildred Delores Jeter July 22, 1939 Central Point, Virginia, U.S. Richard Richard Perry Loving October 29, 1933 Central Point, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | Mildred May 2, 2008 (aged 68) Milford, Virginia, U.S. Richard June 29, 1975 (aged 41) Caroline County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Mildred Housewife Richard Construction worker |

| Known for | Plaintiffs in Loving v. Virginia (1967) |

| Children | 3 |

With the exception of a 2007 statement supporting LGBT rights, Mildred lived "a quiet, private life declining interviews and staying clear of the spotlight" after Loving and the death of her husband.[1][2][5] On the 40th anniversary of the decision, she stated: "I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard's and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight, seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That's what Loving, and loving, are all about."[2][6] Beginning in 2013, the case was cited as precedent in U.S. federal court decisions holding restrictions on same-sex marriage unconstitutional, including in the U.S. Supreme Court decision Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).[7]

Early life and marriage

editMildred Jeter was the daughter of Musial (Byrd) Jeter and Theoliver Jeter.[8] She was born and raised in the small community of Central Point in Caroline County, Virginia. Mildred identified culturally as Native American, specifically Rappahannock,[9] a historic and now a federally recognized tribe in Virginia. (She was reported to have Cherokee, Portuguese, and African American ancestry.)[10][11] She is often described as having Native American and African American ancestry.[12][13]

Richard Loving was the son of Lola (Allen) Loving and Twillie Loving. He was also born and raised in Central Point, where he became a construction worker after school.[14] He was European American, classified as white. His father's maternal grandfather, T. P. Farmer, fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.[15]

Caroline County adhered to the state's strict 20th-century Jim Crow segregation laws, but Central Point had been a visible mixed-race community since the 19th century.[12] Virginia's one-drop rule, codified in law in 1924 as the Racial Integrity Act, required all residents to be classified as "white" or "colored", refusing to use people's longstanding identification as Indian among several tribes in the state.

Richard's father worked for one of the wealthiest black men in the county for 25 years. Richard's closest companions were black (or colored, as was the term then), including those he drag-raced with and Mildred's older brothers. "There's just a few people that live in this community," Richard said. "A few white and a few colored. And as I grew up, and as they grew up, we all helped one another. It was all, as I say, mixed together to start with and just kept goin' that way."[16]

The two first met when Mildred was 11 and Richard was 17.[17] He was a family friend of her brothers. Years later, when she was in high school, they began dating. When Mildred was 18 she became pregnant and Richard moved into the Jeter household.[citation needed] They decided to marry in June 1958 and traveled to Washington, D.C., to do so.

At the time, interracial marriage was banned in Virginia by the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. Mildred later stated that when they married, she did not realize their marriage was illegal in Virginia but she later believed her husband had known it.[18]

After their marriage, the Lovings returned home to Central Point. They were arrested at night by the county sheriff who had received an anonymous tip,[19] and charged with "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth." They pled guilty and were convicted by the Caroline County Circuit Court on January 6, 1959. They were sentenced to one year in prison, suspended for 25 years on the condition that they leave the state. They moved to Washington, D.C., but missed their country town.

They were frustrated by their inability to travel together to visit their families in Virginia, and by social isolation and financial difficulties in Washington, D.C. In 1964, after their youngest son was hit by a car in the busy streets, they decided they needed to move back to their home town, and they filed suit to vacate the judgment against them so they would be allowed to return home.[20]

Supreme Court case

editIn 1964,[20] Mildred Loving wrote in protest to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Kennedy referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union.[19]

The ACLU filed a motion on the Lovings' behalf to vacate the judgment and set aside the sentence, on the grounds that the statutes violated the Fourteenth Amendment. This began a series of lawsuits and the case ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court. On October 28, 1964, when their motion still had not been decided, the Lovings began a class action suit in United States district court. On January 22, 1965, the district court allowed the Lovings to present their constitutional claims to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. Virginia Supreme Court Justice Harry L. Carrico (later Chief Justice) wrote the court's opinion upholding the constitutionality of the anti-miscegenation statutes and affirmed the criminal convictions.

The Lovings and ACLU appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Lovings did not attend the oral arguments in Washington, but their lawyer, Bernard S. Cohen, conveyed a message from Richard Loving to the court: "[T]ell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."[21]

The case, Loving v. Virginia, was decided unanimously in the Lovings' favor on June 12, 1967. The Court overturned their convictions, dismissing Virginia's argument that the law was not discriminatory because it applied equally to and provided identical penalties for both white and black persons. The Supreme Court ruled that the anti-miscegenation statute violated both the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Lovings returned to Virginia after the Supreme Court decision.

Later life

editThe Lovings had two children together: Donald Lendberg Loving (October 8, 1958 – August 2000) and Peggy Loving (born c. 1960). Mildred's oldest, Sidney Clay Jeter (January 27, 1957 – May 2010), was born in Caroline County prior to her relationship with Richard. He lived with the Lovings. Each of the children married and had their own families. At the time of her death, Mildred had eight grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren.[22]

After the Supreme Court ruled on the case in 1967, the couple moved with their children back to Central Point, Virginia, where Richard built them a house. This was their home for the rest of their lives.

Mildred said she considered her marriage and the court decision to be "God's work". She supported everyone's right to marry whomever they wished.[23] In 1965, while the case was pending, she told the Washington Evening Star, "We loved each other and got married. We are not marrying the state. The law should allow a person to marry anyone he wants."[18]

On June 12, 2007, Mildred issued a statement on the 40th anniversary of the Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court decision.[6]

She concluded:

My generation was bitterly divided over something that should have been so clear and right. The majority believed that what the judge said, that it was God's plan to keep people apart, and that government should discriminate against people in love. But I have lived long enough now to see big changes. The older generation's fears and prejudices have given way, and today's young people realize that if someone loves someone they have a right to marry.

Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don't think of Richard and our love, our right to marry, and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the "wrong kind of person" for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people's religious beliefs over others. Especially if it denies people's civil rights.

I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard's and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That's what Loving, and loving, are all about.

Deaths

editOn June 29, 1975, a drunk driver struck the Lovings' car in Caroline County, Virginia.[4] Richard was killed in the crash, at age 41. Mildred lost her right eye.

Mildred died of pneumonia on May 2, 2008, in Milford, Virginia, at age 68. Her daughter, Peggy Loving Fortune, said, "I want [people] to remember her as being strong and brave, yet humble—and believ[ing] in love."[18]

The final sentence in Mildred Loving's obituary in the New York Times notes her statement to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia:[24] "A modest homemaker, Loving never thought she had done anything extraordinary. 'It wasn't my doing,' Loving told the Associated Press in a rare interview [in 2007]. 'It was God's work.'"[25]

Legacy

edit- Mr. and Mrs. Loving, a 1996 film starring Lela Rochon, Timothy Hutton and Ruby Dee, written and directed by Richard Friedenberg. It aired on the Showtime network. According to Loving, "Not much of it was very true. The only part of it right was I had three children."[26]

- Phyl Newbeck (2004). Virginia Hasn't Always Been for Lovers. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2528-4.

- June 12 has become known as Loving Day in the United States, an unofficial holiday celebrating interracial marriages.

- The Loving Story (2011), an HBO-produced documentary which was screened at many film festivals, including Silverdocs Documentary Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, and Full Frame Documentary Film Festival. The film includes rare interviews, photographs and film shot during the time.

- Loving, a 2016 film by Jeff Nichols inspired by The Loving Story, starring Joel Edgerton as Richard Loving and Ruth Negga as Mildred Loving.

- "The Loving Kind" is a song written by country/folk singer-songwriter Nanci Griffith. It was included in Griffith's 2009 album "The Loving Kind"

References

edit- ^ a b Lopez, Tyler (February 14, 2014). "The Simple Justice of Marriage Equality in Virginia". Slate Magazine. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

The legacy of Loving v. Virginia weighs heavily on the pages of Judge Wright Allen's opinion, which opens with a quote from Mildred Loving—who was a vocal supporter of same-sex marriage—before discussing the case at hand.

- ^ a b c Holland, Brynn (October 28, 2018). "Mildred and Richard: The Love Story that Changed America". HISTORY. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

Mildred lived a quiet, private life declining interviews and staying clear of the spotlight. She did, however, make a rare exception in June of 2007. On the 40th anniversary of the Loving v. Virginia ruling... [the] devoutly religious Mildred issued a statement that read, in part, "I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people's religious beliefs over others. Especially if it denies people's civil rights." There is little doubt about Mildred and Richard's legacy.

- ^ Loving v. Virginia 388 U.S. 1 (1967)

- ^ a b "Richard P. Loving; In Land Mark Suit; Figure in High Court Ruling on Miscegenation Dies". The New York Times. July 1, 1975.

- ^ Dominus, Susan (December 24, 2008). "The Color of Love". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Freedom To Marry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 14-556, 576 U.S. ___ (2015)

- ^ "Mildred Loving obituary". Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ Coleman, Arica L. (June 10, 2016). "What You Didn't Know About Loving v. Virginia". Time. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Lawing, Charles B. "Loving v. Virginia and the Hegemony of 'Race'" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Dionne (June 10, 2007). "Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Staples, Brent (May 14, 2008). "Loving v. Virginia and the Secret History of Race". Opinion. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ D, Elle. "Mildred Loving's Grandson Reveals She Didn't Identify, and Hated Being Portrayed, as Black American". bglh-marketplace. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Lavender, Abraham (2014). "Loving, Richard (1933–1975), and Mildred Loving (1939–2008)". In Chapman, Roger; Ciment, James (eds.). Culture Wars in America: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices (2nd ed.).

- ^ Coleman, Arica L. (November 4, 2016). "The White and Black Worlds of 'Loving v. Virginia'". Time. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "The Loving Couple". The Attic. November 16, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Robert A. Pratt (2015). "Crossin the Color Line: A Historical Assessment and Personal Narrative of Loving v. Virginia". In Weisberg, D. Kelly; Appleton, Susan Frelich (eds.). Modern Family Law: Cases and Materials (6 ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer. p. 135.

- ^ a b c "Matriarch of racially mixed marriage dies". MSNBC. May 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Martin, Douglas (May 6, 2008). "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Mildred Loving, Key Figure in Civil Rights Era, Dies". PBS NewsHour. May 6, 2008.

- ^ Sheppard, Kate (February 13, 2012). "'The Loving Story': How an Interracial Couple Changed a Nation". Mother Jones. Also quoted in "Loving v. Virginia (1967)". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ^ Malhotra, Noor (November 17, 2020). "Where Are Richard and Mildred Loving's Children Now?". The Cinemaholic. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Walker, Dionne (June 9, 2007). "40 years of interracial marriage: Mildred Loving reflects on breaking the color barrier". The Standard-Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (May 6, 2008). "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

Mildred Loving, a black woman whose anger over being banished from Virginia for marrying a white man led to a landmark Supreme Court ruling overturning state miscegenation laws, died on May 2 at her home in Central Point, Va. She was 68.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (May 6, 2008). "Quiet Va. Wife Ended Interracial Marriage Ban". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Walker, Dionne (June 10, 2007). "Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back". USA Today. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

External links

edit- Joanna Grossman, "The Fortieth Anniversary of Loving v. Virginia: The Personal and Cultural Legacy of the Case that Ended Legal Prohibitions on Interracial Marriage", Findlaw commentary

- under Virginia's anti-miscegenation law. David Margolick, "A Mixed Marriage's 25th Anniversary of Legality", New York Times, June 12, 1992

- June 12, 2007 "Loving Day statement by Mildred Loving" Archived October 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ABC News: "A Groundbreaking Interracial Marriage; Loving v. Virginia at 40.", ABC News interview with Mildred Jeter Loving; video clip of original 1967 broadcast, accessed June 14, 2007

- "Mr. & Mrs. Loving". IMDb.

- Lovingday.org

- "A Stance for Love" Archived February 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Bain Journal