Min (Ancient Egyptian: mnw),[1] also called Menas,[a] is an ancient Egyptian god whose cult originated in the predynastic period (4th millennium BCE).[2] He was represented in many different forms, but was most often represented in male human form, shown with an erect penis which he holds in his right hand and an upheld left arm holding a flail.

| Min | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

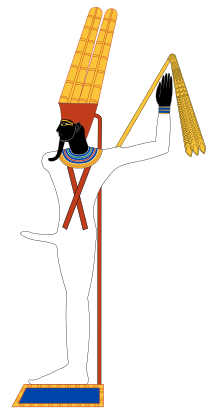

The dark-skinned fertility god Min, with an erect penis and a "flail" | ||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| |||

| Major cult center | Qift, Akhmim | |||

| Symbol | the lettuce, the phallus, the bull, the belemnite | |||

| Parents | Isis | |||

| Consort | Iabet Repyt Isis | |||

| Equivalents | ||||

| Greek | Pan, Priapus | |||

Myths and function

editMin's cult began and was centered around Coptos (Koptos) and Akhmim (Panopolis) of upper Egypt,[4] where in his honour great festivals were held celebrating his "coming forth" with a public procession and presentation of offerings.[2] His other associations include the eastern desert and links to the god Horus. Flinders Petrie excavated two large statues of Min at Qift which are now in the Ashmolean Museum and it is thought by some that they are pre-dynastic. Although not mentioned by name, a reference to "he whose arm is raised in the East" in the Pyramid Texts is thought to refer to Min.[5]

His importance grew in the Middle Kingdom when he became even more closely linked with Horus as the deity Min-Horus. By the New Kingdom he was also fused with Amun in the form of Min-Amun, who was also the serpent Irta, a kamutef (the "bull of his mother" - a god who fathers himself with his own mother.[6] The kamutf name is also used in reference to Horus-Min[7]). Min as an independent deity was also a kamutef of Isis. One of Isis's many places of cult throughout the valley was at Min's temple in Koptos as his divine wife.[8] Min's shrine was crowned with a pair of bull horns.[5]

As the central deity of fertility and possibly orgiastic rites, Min became identified by the Greeks with the god Pan. One feature of Min worship was the wild prickly lettuce Lactuca serriola – the domestic version of which is Lactuca sativa (lettuce) – which has aphrodisiac and opiate qualities and produces latex when cut, possibly identified with semen. He also had connections with Nubia. However, his main centers of worship remained at Coptos and Akhmim (Khemmis).[9]

Male deities as vehicles for fertility and potency rose to prevalence at the emergence of widespread agriculture. Male Egyptians would work in agriculture, making bountiful harvests a male-centered occasion. Thus, male gods of virility such as Osiris and Min were more developed during this time. Fertility was not associated with solely women, but with men as well, even increasing the role of the male in childbirth.[10] As a god of male sexual potency, he was honoured during the coronation rites of the New Kingdom, when the Pharaoh was expected to sow his seed—generally thought to have been plant seeds. At the beginning of the harvest season, his image was taken out of the temple and brought to the fields in the festival of the departure of Min, the Min Festival, when they blessed the harvest, and played games naked in his honour, the most important of these being the climbing of a huge (tent) pole. This four day festival is evident from the great festivals list at the temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu.[8][11]

Cult and worship in the predynastic period surrounding a fertility god was based upon the fetish of fossilized belemnite.[10] Later symbols widely used were the white bull, a barbed arrow, and a bed of lettuce, that the Egyptians believed to be an aphrodisiac. Egyptian lettuce was tall, straight, and released a milk-like sap when rubbed, characteristics superficially similar to the penis. Lettuce was sacrificially offered to the god, then eaten by men in an effort to achieve potency.[10] Later pharaohs would offer the first fruits of harvest to the god to ensure plentiful harvest, with records of offerings of the first stems of sprouts of wheat being offered during the Ptolemaic period.[10]

Civilians who were not able to formally practice the cult of Min paid homage to the god as sterility was an unfavorable condition looked upon with sorrow. Concubine figurines, ithyphallic statuettes, and ex-voto phalluses were placed at entrances to the houses of Deir el-Medina to honor the god in hopes of curing the disability.[10] Egyptian women would touch the penises of statues of Min in hopes of pregnancy, a practice still continued today.[10]

Appearance

editIn Egyptian art, Min is depicted as an anthropomorphic male deity with a masculine body, covered in shrouds, wearing a crown with feathers, and often holding his erect penis in his left hand and a "flail" that is possibly a stylised form of flail (referring to his authority, or rather that of the Pharaohs) in his upward facing right hand. Around his forehead, Min wears a red ribbon that trails to the ground, claimed by some to represent sexual energy. The legs are bandaged because of his chthonic force, in the same manner as Ptah and Osiris.[8] His skin was usually painted black, which symbolized the fertile soil of the Nile.[12][13][14]

Family

editIn Hymn to Min it is said:

Min, Lord of the Processions, God of the High Plumes, Son of Osiris and Isis, Venerated in Ipu...

Ejaculation legend

editThere have been controversial suggestions, by authors such as British journalist Jonathan Margolis, that the pharaoh was expected to demonstrate, as part of a Min festival, that he could ejaculate—and thus ensure the annual flooding of the Nile.[16] No hard evidence of this exists, according to Egyptologists Kara Cooney, professor of ancient Egyptian art and architecture at UCLA, and her colleague Jonathan Winnerman. This myth may have originated from a misinterpretation of a different festival.[17]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Ancient Greek: Μηνᾶς, romanized: Mēnâs, Greek pronunciation: [mɛː.nâːs]

References

edit- ^ Allen, James (2014). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-107-66328-2.

- ^ a b "Min". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2020. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 116

- ^ Alan., Lothian (2012). Ancient Egypt's myths and beliefs. Rosen Pub. ISBN 978-1-4488-5994-8. OCLC 748941784.

- ^ a b Frankfort, Henry (1978). Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature. University of Chicago Press. pp. 187–189. ISBN 978-0-226-26011-2.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 93. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ The Conflict of Horus and Set, J G Griffiths, 1960 page 49

- ^ a b c Christiane, Zivie-Coche (2004). Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-8014-4165-3. OCLC 845667204.

- ^ Manchip, White, J. E. (2013). Ancient Egypt: Its Culture and History. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22548-7. OCLC 868271431.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Najovits, Simson R. (2004). Egypt, trunk of the tree: a modern survey of an ancient land. Algora Pub. pp. 68, 93. ISBN 978-0-87586-222-4. OCLC 51647593.

- ^ "Festivals in the ancient Egyptian calendar". University College London. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- ^ Orlin, Eric (2015-11-19). Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62552-9.

- ^ Power, Mick (2012-01-06). Adieu to God: Why Psychology Leads to Atheism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-97995-1.

- ^ Sabbahy, Lisa K. (2019-04-24). All Things Ancient Egypt: An Encyclopedia of the Ancient Egyptian World [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-5513-9.

- ^ Bagnall, Director of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World Roger S. (2004). Egypt from Alexander to the Early Christians: An Archaeological and Historical Guide. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-796-2.

- ^ O : the intimate history of the orgasm (2004) by Margolis, Jonathan, p. 134. He seems to be based on an earlier collection of unusual sex practices.

- ^ "Egyptian pharaohs didn't masturbate into Nile".

Further reading

edit- McFarlane, Ann. (1995). The God Min to the End of the Old Kingdom. Australian Center for Egyptology. ISBN 9780856686788.

External links

edit- Site on Min, with some pictures Archived 2015-01-20 at the Wayback Machine