Minesweeper is a logic puzzle video game genre generally played on personal computers. The game features a grid of clickable tiles, with hidden "mines" (depicted as naval mines in the original game) scattered throughout the board. The objective is to clear the board without detonating any mines, with help from clues about the number of neighboring mines in each field. Variants of Minesweeper have been made that expand on the basic concepts, such as Minesweeper X, Crossmines, and Minehunt. Minesweeper has been incorporated as a minigame in other games, such as RuneScape and Minecraft's 2015 April Fools update.

The origin of Minesweeper is unclear. According to TechRadar, the first version of the game was 1990's Microsoft Minesweeper, but Eurogamer says Mined-Out by Ian Andrew (1983) was the first Minesweeper game. Curt Johnson, the creator of Microsoft Minesweeper, acknowledges that his game's design was borrowed from another game, but it was not Mined-Out, and he does not remember which game it is.

Gameplay

editMinesweeper is a puzzle video game.[1] In the game, mines (that resemble naval mines in the classic theme) are scattered throughout a board, which is divided into cells. Cells have three states: unopened, opened and flagged. An unopened cell is blank and clickable, while an opened cell is exposed. Flagged cells are those marked by the player to indicate a potential mine location.[2]

A player selects a cell to open it. If a player opens a mined cell, the game ends. Otherwise, the opened cell displays either a number, indicating the number of mines diagonally and/or adjacent to it, or a blank tile (or "0"), and all adjacent non-mined cells will automatically be opened. Players can also flag a cell, visualised by a flag being put on the location, to denote that they believe a mine to be in that place.[1] Flagged cells are still considered unopened, and a player can click on them to open them.[2] In some versions of the game when the number of adjacent mines is equal to the number of adjacent flagged cells, all adjacent non-flagged unopened cells will be opened, a process known as chording.[2]

Objective and strategy

editA game of Minesweeper begins when the player first selects a cell on a board. In some variants the first click is guaranteed to be safe, and some further guarantee that all adjacent cells are safe as well.[3] During the game, the player uses information given from the opened cells to deduce further cells that are safe to open, iteratively gaining more information to solve the board. The player is also given the number of remaining mines in the board, known as the minecount, which is calculated as the total number of mines subtracted by the number of flagged cells (thus the minecount can be negative if too many flags have been placed).[4]

To win a game of Minesweeper, all non-mine cells must be opened without opening a mine. There is no score, but there is a timer recording the time taken to finish the game. Difficulty can be increased by adding mines or starting with a larger grid. Most variants of Minesweeper that are not played on a fixed board offer three default board configurations, usually known as Beginner, Intermediate, and Expert, in order of increasing difficulty. Beginner is usually on an 8x8 or 9x9 board containing 10 mines, Intermediate is usually on a 16x16 board with 40 mines and expert is usually on a 30x16 board with 99 mines; however, there is usually an option to customise board size and mine count.[2]

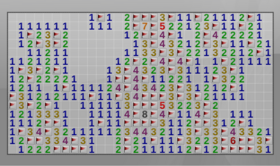

- An example beginner (9x9) difficulty Minesweeper game from start to solved state

History

editAccording to TechRadar, Minesweeper was created by Microsoft in the 1990s,[5] but Eurogamer commented that Minesweeper gained a lot of inspiration from a "lesser known, tightly designed game", Mined-Out by Ian Andrew for the ZX Spectrum in 1983.[6] According to Andrew, Microsoft copied Mined-Out for Microsoft Minesweeper.[6] The Microsoft version made its first appearance in 1990, in Windows Entertainment Pack, which was given as part of Windows 3.11.[6][1] The game was written by Robert Donner and Curt Johnson.[5][6] Johnson stated that Microsoft Minesweeper's design was borrowed from another game, but it was not Mined-Out, and he does not remember which game it was.[6] In 2001, a group called the International Campaign to Ban Winmine campaigned for the game's topic to be changed from landmines.[5] The group commented that the game "is an offence against the victims of the mines".[7] A later version, found present in Windows Vista's Minesweeper, offered a tileset with flowers replacing mines as a response.[5][1]

The game is frequently bundled with operating systems and desktop environments, including Minesweeper for IBM's OS/2, Microsoft Windows, KDE, GNOME and Palm OS.[8] Microsoft Minesweeper was included by default in Windows until Windows 8 (2012).[9] Microsoft replaced this with a free-to-play version of the game, downloadable from the Microsoft Store, which is "riddled with ads", according to How-To Geek.[9][1]

Variants

editVariants of Minesweeper have been made that expand on the basic concepts and add new game design elements. Minesweeper X is a clone of the Microsoft version with improved randomization and more statistics,[6][1] and is popular with players of the game intending to reach a fast time.[6] Arbiter and Viennasweeper are also clones, and are used similarly to Minesweeper X.[6] Crossmines is a more complex version of the game's base idea, adding linked mines and irregular blocks.[5] BeTrapped transposes the game into a mystery game setting.[5] There are several direct clones of Microsoft Minesweeper available online.[1]

Minesweeper Q was released in 2011 by the independent developer Spica[10] and is another clone of the Microsoft version available as a mobile and tablet app for iOS users. It includes quick flagging and quick open mode. Users also have the option to change their board appearance from the classic gray/mines to flowers or clouds. Because this version is limited to use on mobile and iPad it is not ideal for players aiming to reach a fast time.

Minesweeper was made part of RuneScape through a minigame called Vinesweeper.[6] The non-Japanese releases of Pokémon HeartGold and SoulSilver contained a variation of both Minesweeper and Picross.[11] The video game Minecraft released a version of Minesweeper in its 2015 April Fool's update.[12] The HP-48G graphing calculator includes a variant called "Minehunt", where the player has to move safely from one corner of the playfield to the other. The only clues given are how many mines are in the squares surrounding the player's current position.[13] Google search includes a version of Minesweeper as an easter egg, available by searching the game's name.[14]

A logic puzzle variant of minesweeper, suitable for playing on paper, starts with some squares already revealed. The player cannot reveal any more squares, but must instead mark the remaining mines correctly. Unlike the usual form of minesweeper, these puzzles usually have a unique solution. These puzzles appeared under the name "tentaizu" (天体図), Japanese for a star map, in Southwest Airlines' magazine Spirit in 2008–2009.[15]

-

A tentaizu puzzle

-

Online, non-rectangular

-

3D

-

Hexagonal

-

Triangular

-

Multiple mines in cells

-

Emoji minesweeper

Competitive play

editCompetitive Minesweeper players aim to complete the game as fast as possible. The players memorize patterns to reduce times.[1] Some players use a technique called the "1.5 click", which aids in revealing mines, while other players do not flag mines at all.[1] The game is played competitively in tournaments.[1] A community of dedicated players has emerged; this community was centralized on websites such as Minesweeper.info.[6] As of 2015, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the fastest time to complete all three difficulties of Minesweeper is 38.65 seconds by Kamil Murański in 2014.[1]

Computational complexity

editIn 2000, Sadie Kaye[16] published a proof that it is NP-complete to determine whether a given grid of uncovered, correctly flagged, and unknown squares, the labels of the foremost also given, has an arrangement of mines for which it is possible within the rules of the game. The argument is constructive, a method to quickly convert any Boolean circuit into such a grid that is possible if and only if the circuit is satisfiable; membership in NP is established by using the arrangement of mines as a certificate.[17] If, however, a minesweeper board is already guaranteed to be consistent, solving it is not known to be NP-complete, but it has been proven to be co-NP-complete.[18] In the latter case, however, minesweeper exhibits a phase transition analogous to k-SAT: when more than 25% squares are mined, solving a board requires guessing an exponentially-unlikely set of mines.[19] Kaye also proved that infinite Minesweeper is Turing-complete.[20]

See also

editReferences

editInline citations

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Edwards, Benj (8 October 2020). "30 Years of 'Minesweeper' (Sudoku with Explosions)". How-To Geek. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d "How To Play Minesweeper". Authoritative Minesweeper. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Minesweeper Strategy - First Click". Authoritative Minesweeper. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

Windows Vista introduced guaranteed openings [a cell with no adjacent mines] on the first click...

- ^ Leonhard, Woody (19 August 2009). Windows 7 All-in-One For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470550168 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Cobbett, Richard (5 May 2009). "The most successful game ever: a history of Minesweeper". TechRadar. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Every step you take: The story of Minesweeper". Eurogamer.net. 20 July 2014. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Blincoe, Robert. "Windows Minesweeper is an 'offence to mine victims'". www.theregister.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Team, Gamesver (10 May 2022). "Minesweeper (Game): 25 Fun / Interesting Facts (History, Stats,…)". Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b Edwards, Benj (18 July 2022). "Every Game Microsoft Ever Included in Windows, Ranked". How-To Geek. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Minesweeper Q details". www.metacritic.com. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Scullion, Chris (3 February 2010). "News: Pokémon HeartGold/SoulSilver mini-game revealed! - Official Nintendo Magazine". officialnintendomagazine.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Every Minecraft April Fools Joke (Including 2022)". ScreenRant. 7 May 2022. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "HP 48 Miscellaneous Games". www.hpcalc.org. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Sidhwani, Priyansh (6 October 2022). "How To Play Google Minesweeper". TechStory. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Minesweeper Puzzles Magazine". www.puzzle-magazine.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Dr Sadie Kaye MA PhD". birmingham.ac.uk. University of Birmingham. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Kaye, Richard (March 2000). "Minesweeper is NP-complete!". Mathematical Intelligencer. 22 (2): 9–15. doi:10.1007/BF03025367. ISSN 1866-7414. S2CID 122435790. Archived from the original on 15 August 2004. Retrieved 20 August 2004.

- ^ Scott, Allan; Stege, Ulrike; van Rooij, Iris (December 2011). "Minesweeper May Not Be NP-Complete but Is Hard Nonetheless". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 33 (4): 5–17. doi:10.1007/s00283-011-9256-x. S2CID 122506352.

- ^ Dempsey, Ross; Guinn, Charles (2020). "A Phase Transition in Minesweeper". arXiv:2008.04116 [cs.AI].

- ^ Kaye, Richard (31 May 2007). "Infinite versions of minesweeper are Turing complete" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

General references

edit- Adamatzky, Andrew (1997). "How cellular automaton plays Minesweeper". Applied Mathematics and Computation. 85 (2–3): 127–137. doi:10.1016/S0096-3003(96)00117-8.

- Lakshtanov, Evgeny; Oleg German (2010). "'Minesweeper' and spectrum of discrete Laplacians". Applicable Analysis. 89 (12): 1907–1916. arXiv:0806.3480. doi:10.1080/00036811.2010.505189. S2CID 17474183.

- Mordechai Ben-Ari (2018). Minesweeper is NP-Complete (PDF) (Report). Weizmann Institute of Science, Department of Science Teaching. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2019. — An open-access paper explaining Kaye's NP-completeness result.