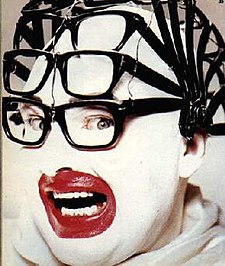

Leigh Bowery (26 March 1961 – 31 December 1994) was an Australian performance artist, club promoter, and fashion designer. Bowery was known for his conceptual, flamboyant, and outlandish costumes and makeup, as well as his (sometimes controversial) live performances.

Leigh Bowery | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 March 1961 |

| Died | 31 December 1994 (aged 33) Westminster, London, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1980–1994 |

| Spouse |

Nicola Bateman (m. 1994) |

Based in London for much of his adult life, he was a significant model and muse[1] for the English painter Lucian Freud. Bowery's friend and fellow performer Boy George said he saw Bowery's outrageous performances a number of times, and that it "never ceased to impress or revolt".[2][3]

Early life and years in London

editBowery was born and raised in Sunshine, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. From an early age, he studied music, played piano, and went on to study fashion and design at RMIT for a year.[4] He moved to London in 1980, saying, "I was so itchy to see new things and to see the world, that I just left."[5]

Bowery soon became part of the London club scene.[6] He became an influential and lively figure in the underground clubs of London and New York, as well as in art and fashion circles. He attracted attention by wearing outlandish and creative outfits, which he made himself. He became friends and flatmates with artist Gary Barnes (known as "Trojan") and David Walls. Bowery created costumes for them to wear, and the trio became known in the clubs as the "Three Kings".[7][8] Bowery often appeared in magazines and on television, including commercials for Pepe Jeans and Rifat Ozbek.[citation needed]

In 2005, the National Portrait Gallery of Australia acquired a portrait of Bowery in his fur coat by the photographer David Gwinnutt. In 2007, the National Portrait Gallery, London purchased Gwinnutt's portrait of Bowery and Trojan (Barnes), which also appears in the Violette Editions book.[citation needed]

Taboo club

editBowery was known as a club promoter, and created the club Taboo at Maximus in Leicester Square with promoter Tony Gordon in 1985.[9] Taboo became "the place to be" with long queues. Drugs, particularly ecstasy, became a part of the dancing scene for the attendees. The club was known for defying sexual convention, for embracing "polysexualism", for creating a wild atmosphere and for playing unexpected song selections. The DJs were Jeffrey Hinton, Rachel Auburn and Mark Lawrence. Regular guests included Boy George, George Michael, John Galliano, Judy Blame, Bodymap, Michael Clark, John Maybury, Cerith Wyn Evans.[10] Taboo lasted 18 months and closed in 1986.

Fashion and costume design

editAs a fashion designer, Bowery had several shows exhibiting his collections in London, New York and Tokyo. He influenced several designers and artists, and was known for wildly creative costumes, makeup, wigs and headgear, all of which combined to be striking and often kitschy.[11] He also designed costumes for the Michael Clark Dance Company. When that company performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1987, Bowery won a Bessie Award for his work on No Fire Escape in Hell.[11][12]

Performance artist

editAs a performance artist, Bowery enjoyed creating the costumes, and often shocking audiences. Working alongside Michael Clark, he would often have solo scenes in many of Clark's shows.[citation needed]

His first one-man installation was in 1988 for a week at the Anthony D'Offay Gallery in London. Hidden behind a two way mirror he would lay on a 19th Century divan, primping and preening himself at his own reflection, while the audience would watch sat on the floor from the other side. Each day he changed costumes and so visitors would often came back to see what he would be wearing next. Various traffic sounds would be played over the speaker system during the performance and there was a different smell every day, including bananas.[citation needed]

In 1990 at the London club night 'Kinky Gerlinky' he introduced his signature 'Birthing' performance. Dressed as the drag performer Divine from 'Female Trouble' he appeared on stage in an oversized t-shirt, dark glasses and headscarf, looking huge and miming along to the film dialogue. Then suddenly, much to the audience's surprise, he drops onto his back and simulate 'giving birth' to his baby, a petite and naked young woman who was his friend, assistant and later wife Nicola Bateman.[2][3]She had been hidden for the first part of the performance by being strapped to Leigh's belly with her face in his crotch. Then she would slip out of her harness and appear to pop out of Bowery's belly, bursting through his tights, along with a lot of stage blood and links of sausages, while Bowery wailed. Bowery would then bite off the umbilical cord, hug his 'new' baby and the two would take a bow. Boy George said he saw it a number of times, and that it "never ceased to impress or revolt".[2][3] Bowery used this birthing performance during his live shows with Minty, with additional vomit in cups and urine involved.[citation needed]

In mid-1994 one of Bowery's last performances took place at the Fort Asperen Art Festival in Holland, where he and his assistant Nicola and bass player Richard Torry performed to a bemused crowd during the day and fully naked, Richard covered in bright blue balloons. Bowery hangs upside down singing into the microphone while Richard pulls him back and forth by the foot until the climax of the song and Bowery smashes himself through a plane of glass, cutting his body. The whole performance lasts 5 minutes.[citation needed]

Lucian Freud's model

editIn London in 1988, Bowery met the noted painter Lucian Freud in his club Taboo. They were introduced by a friend they had in common, the artist Cerith Wyn Evans. Freud had seen Bowery perform at Anthony d'Offay Gallery, in London. In Bowery's first public appearance in the context of fine art, Bowery posed behind a one-way mirror in the gallery dressed in the flamboyant costumes he was known for.

Bowery used his body and manipulation of his flesh to create personas. This involved almost masochistically taping his torso and piercing his cheeks with pins in order to hold masks, as well as wearing outlandish makeup. Freud said, "the way he edits his body is amazingly aware and amazingly abandoned". In return, Bowery said of Freud: "I love the psychological aspect of his work – in fact, I sometimes felt as if I had been undergoing psychoanalysis with him ... His work is full of tension. Like me, he is interested in the underbelly of things".[13]

Bowery posed for a number of large full-length paintings that are considered among Freud's best work. The paintings tend to exaggerate Bowery's 6-foot 3inch, 17-stone physique to monumental proportions. The paintings had a strong impact as part of Freud's exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1994. Freud said he found him "perfectly beautiful", and commented, "His wonderfully buoyant bulk was an instrument I felt I could use, especially those extraordinary dancer's legs". Freud noted that Leigh by nature was a shy and gentle man, and his flamboyant persona was in part a form of self-defence.[14][15][16][17]

Jonathan Jones, writing for The Guardian, describes Freud's portrait, Leigh Bowery (seated):[18]

Bowery is a character out of Renaissance art - perhaps Silenus, the companion of Dionysus. His flesh is a magnificent ruin, at once damaged and riotously alive. Who knew skin was so particoloured? To count the hues of even one of his feet is impossible: purple, grey, yellow, brown, the paint creamy, calloused, bulging. In a velvet chair tilted down towards us on the raked stage of the wooden studio floor, his mass looms up and dwarfs us. Walk close your eyes are probably the height of his penis. Bowery's violet-domed, wrinkly tube hangs between thighs marked with sinister spots or cuts his knees are massive. Bowery is a painted monument who quietly contemplates his existence inside this flesh.

Minty

editIn 1993, Bowery formed the Romo[19]/ art-pop[20] band Minty with friend knitwear designer Richard Torry, Nicola Bateman, and Matthew Glamorre.

In November 1994, Minty began a two-week-long show at London's Freedom Cafe, including audience member Alexander McQueen, but it was too much for Westminster City Council, who closed down the show after only one night. This was to be Bowery's last performance. The show was documented by photographer A.M. Hanson with imagery subsequently published in books about Bowery[21][22] and McQueen.[23][24]

Minty was a financial loss and represented a low point in Bowery's colourful career. After his death, the band continued under the leadership of Bateman and Glammore up until the release of album Open Wide. This 1997 album was released on Candy Records and featured the singles "Useless Man",[25] "Plastic Bag", "Nothing" and "That's Nice". A spin-off band called The Offset later formed including artist Donald Urquhart.[26]

In 2020, Open Wide was re-issued by Candy Records in association with The state51 Conspiracy, while "Useless Man" received a remix by Boy George and a new promo video directed by Torry and Glammore.[20]

Personal life

editAlthough Bowery was openly gay, he married his long-time female companion Nicola Bateman on 13 May 1994 in Tower Hamlets, London, in "a personal art performance". Although he had been HIV positive for six years, very few of those who knew him guessed that; he typically explained his public absence by saying he had gone to Papua New Guinea.[27]

His wife did not know that Bowery had HIV until he was admitted to hospital in late November 1994. He died seven months after their marriage, on New Year's Eve 1994 (the date has been disputed by his father, who says he actually died in the early hours of New Year's Day, 1995),[28] from an AIDS-related illness at the Middlesex Hospital, Westminster, London, five weeks after his admission.[29] Lucian Freud paid for Bowery's body to be repatriated to Australia.

Taboo, the musical

editBoy George was the creative force, the lyricist and performer in the musical Taboo, which was loosely based on Bowery's club. The musical was produced in 2002 on the West End in London, and then opened on Broadway. As a performer, Boy George played Bowery.[30]

In an interview conducted by Mark Ronson for Interview Magazine Boy George said that Bowery would sometimes speak with a posh English accent, and one didn't always know if he was sincere or mocking: He seemed to be "in character" at all times. Bowery decorated his flat in a style that was similar to the way he dressed, with Star Trek-themed wallpaper, mirrors and a large piano. He was a ringleader of misbehaviour, and with his club, he created a place where there were no rules. In the clubs at the peak of his fame, he would distort his body in various ways so that he would appear deformed, or pregnant or with breasts. Bowery once said, "Flesh is my most favourite fabric".[3]

In popular culture

editBowery influenced other artists and designers including Meadham Kirchhoff, Alexander McQueen, Lucian Freud, Vivienne Westwood, Boy George, Antony and the Johnsons, Lady Gaga, John Galliano, Scissor Sisters, David LaChapelle, Lady Bunny, Acid Betty, Shea Couleé, and Charles Jeffrey plus numerous Nu-Rave bands and nightclubs in London and New York City.[citation needed]

Bowery was the main inspiration for the Tranimal drag movement, which emphasised an animalistic and post-modern take on drag.[31][32]

Bowery was the subject of a contemporary dance, physical theatre and circus show in August 2018 at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, put on by Australian choreographer Andy Howitt.[9][33]

Publications

edit- Leigh Bowery Verwandlungskünstler, editor Angela Stief, published by Piet Meyer Verlag, Vienna, (2015); ISBN 978-3-90579-931-6

- Leigh Bowery Looks, by Leigh Bowery, Fergus Greer, published by Thames & Hudson Ltd; New Ed edition (2005); ISBN 0-500-28566-7

- Leigh Bowery Looks by Leigh Bowery, Fergus Greer, published by Violette Editions (2006); ISBN 1-900-82827-8

- Leigh Bowery, Violette Editions, London, (1998), ISBN 978-1-90082-804-8

- Take a Bowery: The Art and (larger Than) Life of Leigh Bowery, Retrospective catalogue, Gary Carsley, Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney (MCA) Sydney, Australia (2003), ISBN 1875632905, ISBN 978-1875632909

- Leigh Bowery: Fabulous Master of Disguise, Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney (MCA)/Darian Zam Publishing, Sydney, Australia (2003), Tate Modern/Darian Zam Publishing, London, England (2025).

Discography

editMinty

editAlbum

edit- Open Wide (Candy Records, CAN 2LP/CAN 2CD, LP/CD, 1997)[34]

All tracks are written by Minty

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Procession" | 4:53 |

| 2. | "Minty" | 3:56 |

| 3. | "That's Nice" | 3:27 |

| 4. | "Plastic Bag" | 3:35 |

| 5. | "Useless Man" | 4:21 |

| 6. | "Homage (Duet For Piano And Wineglass)" | 1:28 |

| 7. | "Manners Mean" | 2:20 |

| 8. | "King Size" | 4:32 |

| 9. | "Hold On" | 3:26 |

| 10. | "Nothing" | 3:46 |

| 11. | "Homme Aphrodite (Part 1)" | 3:34 |

| 12. | "Homme Aphrodite (Part 2)" | 2:46 |

| 13. | "Dream" | 1:28 |

| 14. | "Art?" | 4:22 |

| 15. | "Jeremy" | 3:53 |

Singles

edit| Year | Title (Format) | Tracks | (Label) Cat# |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Useless Man (CD, Maxi) | "Useless Man" | (Candy Records) CAN 1CD[34] |

| 1995 | Plastic Bag (CD, Maxi) | "Plastic Bag", "Minty (Live)" | (Sugar) SUGA6CD[34] |

| 1996 | That's Nice (CD, Single) | "That's Nice" | (Sugar) SUGA 10CD[34] |

| 1997 | Nothing (CD) | "Nothing", "Carol Ginger Baker" | (Candy Records) CAN3CD[34] |

All singles also included multiple remixes of the lead tracks.[34]

The Offset

editCompilation album

edit- The Offset Presents Minty – It's A Game - Part I (Poppy Records, POPPYCD6, 1997)[34]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "It's A Game - Part I (Radio Edit)" | Minty | 3:27 |

| 2. | "Isadora Grand Prix" | That Donald, Donald Urquhart | 1:42 |

| 3. | "Glug Glug Car" | Sexton Ming, Billy Childish | 3:23 |

| 4. | "Extract" | Neil Kaczor | 1:59 |

| 5. | "It's A Game - Part I (12" Version)" | Minty | 7:32 |

Partial videography

edit- Hail the New Puritan (1985–6), Charles Atlas

- Because We Must (1987), Charles Atlas

- Generations of Love (1990), Baillie Walsh for Boy George

- Unfinished Sympathy (1991), Art Director for Massive Attack single[35]

- Teach (1992), Charles Atlas

- A Smashing Night Out (1994), Matthew Glamorre

- Death in Vegas (1994), Mark Hasler

- Performance at Fort Asperen (1994)

- Flour (single screen version) (1995), Angus Cook

- U2: Popmart - Live from Mexico City (1997), Dancer during 'Lemon Mix'

- Read Only Memory (estratto) (1998), John Maybury

- “Wigstock: The documentary” (1995), Lady Bunny

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Ellen, Barbara (20 July 2002). "Leigh Bowery, ideal husband". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Richardson, John. "Postscript; Leigh Bowery". The New Yorker. 16 January 1995.

- ^ a b c d Mark Ronson (19 December 2008). "Taboo". Interview Magazine.

- ^ Bowery, Leigh. Hannover, Kunstverein, editor. Zechlin, René, ed. Stuffer, Ute, ed. Leigh Bowery. Kehrer Publications (2008) ISBN 978-3-86828-033-3

- ^ Jillian Burt 'Night Owl Spreads His Wings' Melbourne Age 11 February 1987 p. 18

- ^ "Leigh Bowery, 33, Artist and Model". The New York Times. 7 January 1995.

- ^ "Leigh Bowery, 33, Artist and Model". The New York Times. 7 January 1995.

- ^ "Leigh Bowery Photographed in The Art Room". Getty Images. 1 January 1983. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ a b Cochrane, Lauren (13 August 2018). "Sex, sin and sausages: the debauched brilliance of Leigh Bowery". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Bowery, Leigh. Hannover, Kunstverein, editor. Zechlin, René, ed. Ute StufferLeigh, Ute, ed. Leigh Bowery. Kehrer Publications (2008) ISBN 978-3-86828-033-3

- ^ a b Iain R Webb (1 November 2015). "The night I put Leigh Bowery on the catwalk – and he stole the show". The Guardian.

- ^ Barbara Ellen (20 July 2002). "Leigh Bowery, ideal husband". The Guardian.

- ^ Elizabeth Manchester (March 2003). "Lucian Freud, Leigh Bowery (1991)". Tate Britain.

- ^ Hauser, Kitty. "Leigh Bowery and Lucian Freud: the model and the artist". The Australian. 4 July 2015

- ^ Richardson, John. "Postscript; Leigh Bowery". The New Yorker. 16 January 1995.

- ^ MacDonell, Nancy. In the Know: The Classic Guide to Being Cultured and Cool. Penguin (2007) ISBN 978-1-44061-976-2

- ^ Darren Coffield (2013). Factual Nonsense: The Art and Death of Joshua Compston. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-78088-526-1.

- ^ Jonathan Jones (18 November 2000). "Leigh Bowery (Seated), Lucian Freud (1990)". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Minty feature by Everett True, Romo special feature, Melody Maker 25 November 1995 page 11

- ^ a b "Legendary Art Pop Icons Minty Reissue Open Wide |". Rockshotmagazine.com. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Robert Violette; Leigh Bowery (1998). Leigh Bowery. Violette Editions. ISBN 978-3-86828-033-3.

- ^ Leigh Bowery Verwandlungskünstler, ed: Angela Stief (Piet Meyer Verlag) 2015

- ^ Alexander McQueen The Life and The Legacy, Judith Watt (Harper Design) 2012

- ^ Alexander McQueen Blood Beneath the Skin, Andrew Wilson (Simon & Schuster) 2015

- ^ "minty - useless man (2020 reissue) - resident". Resident-music.com. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Urquhart, Donald (February 2009). "Back in the Gay". Out. ISSN 1062-7928.

- ^ Phillip Hoare (5 January 1995). "Obituaries Leigh Bowery". The Independent. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Michael Winkler (21 September 2017). "A Dilettante's 31 Dot Points on the Unveiling of the Bowery Theatre, St Albans". Meanjin. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017.

- ^ Ian Parker (26 February 1995). "A Bizarre Body of Work | The night-clubs of Eighties London were full of posers; none could pose like Leigh Bowery, who died on New Year's Eve. Outrageous, absurd, tormented, he wanted to turn himself into an art-form. Did he eventually succeed? line standfirst". The Independent. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Charles Spencer (31 January 2002). "Mad About the Boy". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Romano, Tricia (1 December 2009). "How to Become a Tranimal". BlackBook. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Clifton, Jamie (26 June 2012). "Why Be a Tranny When You Can Be a Tranimal?". Vice. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ "Sunshine Boy". Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Minty discography". Discogs.

- ^ "Leigh Bowery Filmography". bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

Further reading

edit- Posthumous New York exhibition prospectus

- Sharkey, Alix. "Saturday Night: Born in Sunshine, died in London". The Independent.

- (IMDB) The Legend of Leigh Bowery, directed by Charles Atlas. 2002, US/France, 88 mins duration

- Tilley, Sue (1999). Leigh Bowery: The Life and Times of an Icon. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-69311-8.

- Leigh Bowery by Robert Violette, published by Violette Editions (London, July 1998).ISBN 978-1-90082-804-8

- Audio

- Video

External links

edit- Michael Winkler. "The Great Unknown Melburnian | A tribute to the prodigious Leigh Bowery" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2014.

- Michael Winkler (21 September 2017). "A Dilettante's 31 Dot Points on the Unveiling of the Bowery Theatre, St Albans". Meanjin. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017.

- Gottschalk, Karl-Peter (1995). "Goodbye to the Boy from Sunshine". Archived from the original on 7 April 2004.

- "Online memorial to Leigh Bowery, Derek Jarman and others". DeadInEngland.webs.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019.

- "The Legacy of Leigh Bowery by friend Donald Urquhart". SHOWstudio. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011.

- "Taboo in London". Albemarle of London - Ticket Agency. Archived from the original on 23 October 2006.

- Grant Steven Holmes (September 2016). "Isn't It Queer: | Exploring Spaces, People and Aesthetics of the Queer Cultural Movement" (PDF). University of Huddersfield. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 January 2019.

- Portraits of Leigh Bowery at the National Portrait Gallery, London