The Italian economic miracle or Italian economic boom (Italian: il miracolo economico italiano or il boom economico italiano) is the term used by historians, economists, and the mass media[1] to designate the prolonged period of strong economic growth in Italy after World War II to the late 1960s, and in particular the years from 1958 to 1963.[2] This phase of Italian history represented not only a cornerstone in the economic and social development of the country—which was transformed from a poor, mainly rural, nation into a global industrial power—but also a period of momentous change in Italian society and culture.[3] As summed up by one historian, by the end of the 1970s, "social security coverage had been made comprehensive and relatively generous. The material standard of living had vastly improved for the great majority of the population."[4]

History

editAfter the end of World War II, Italy was in ruins and occupied by foreign armies, a condition that worsened the chronic development gap towards the more advanced European economies. However, the new geopolitical logic of the Cold War made possible that the former enemy Italy, a hinge-country between Western Europe and the Mediterranean, and now a new, fragile democracy threatened by the proximity of the Iron Curtain and the presence of a strong Communist party,[5] was considered by the United States as an important ally for the Free World, and therefore a recipient of the generous aid provided by the Marshall Plan, receiving $1.5 billion from 1948 to 1952. The end of the Plan, that could have stopped the recovery, coincided with the crucial point of the Korea War (1950–1953), whose demand for metal and other manufactured products was a further stimulus to the growth of every kind of industry in Italy. In addition, the creation in 1957 of the European Common Market, of which Italy was among the founder members, provided more investments and eased exports.

The above-mentioned highly favorable historical backgrounds, combined with the presence of a large and cheap stock of labour force, laid the foundations of a spectacular economic growth. The boom lasted almost uninterrupted until the "Hot Autumn's" massive strikes and social unrest of 1969–1970, that combined with the later 1973 oil crisis, gradually cooled the economy, which has never returned to its heady post-war growth rates. The Italian economy experienced an average rate of growth of GDP of 5.8% per year between 1951 and 1963, and 5.0% per year between 1964 and 1973.[8] Italian rates of growth were second only, but very close, to the West German rates, in Europe, and among the OEEC countries only Japan had been doing better.[9] In 1963, US President John F. Kennedy personally praised Italy's extraordinary economic growth at an official dinner with Italian President Antonio Segni in Rome, stating that "the growth of [...] nation's economy, industry, and living standards in the postwar years has truly been phenomenal. A nation once literally in ruins, beset by heavy unemployment and inflation, has expanded its output and assets, stabilized its costs and currency, and created new jobs and new industries at a rate unmatched in the Western world".[10]

Society and culture

editThe impact of the economic miracle on Italian society was huge. Fast economic expansion induced massive inflows of migrants from rural Southern Italy to the industrial cities of the North. Emigration was especially directed to the factories of the so-called "industrial triangle", the region placed between the major manufacturing centres of Milan and Turin and the seaport of Genoa. Between 1955 and 1971, around 9 million people are estimated to have been involved in inter-regional migrations in Italy, uprooting entire communities and creating large metropolitan areas.[14]

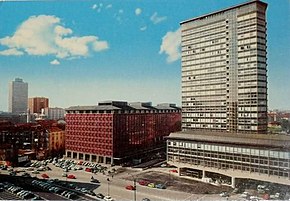

The needs of a modernizing economy and society created a great demand for new transport and energy infrastructures. Thousands of miles of railways and highways were completed in record times to connect the main urban areas, while dams and power plants were built all over Italy, often without regard for geological and environmental conditions. A concurrent boom of the real estate market, increasingly under pressure by strong demographic growth and internal migrations, led to the explosion of urban areas. Vast neighborhoods of low-income apartments and social housing were built in the outskirts of many cities, leading over the years to severe problems of congestion, urban decay and street violence. The natural environment was constantly under strain by unregulated industrial expansion, leading to widespread air and water pollution and ecological disasters like the Vajont Dam disaster and the Seveso chemical accident, until a green consciousness developed starting in the 1980s.

At the same time, the doubling of Italian GDP between 1950 and 1962[15] had a massive impact on society and culture. Italian society, largely rural and excluded from the benefits of modern economy during the first half of the century, was suddenly flooded with a huge variety of cheap consumer goods, such as automobiles, televisions and washing machines. From 1951 to 1971, average per capita income in real terms trebled, a trend accompanied by significant improvements in consumption patterns and living conditions. In 1955, for instance, only 3% of households owned refrigerators and 1% washing machines, while by 1975 the respective figures were 94% and 76%. In addition, 66% of all homes had come to possess cars.[16] In 1954 the national public broadcasting RAI began a regular television service.

Criticism

editThe pervasive influence of the mass media and consumerism on society in Italy has often been fiercely criticized by intellectuals like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Luciano Bianciardi, who denounced it as a sneaky form of homogenization and cultural decay. Popular movies like Il Sorpasso (1962) and I Mostri (1963) by Dino Risi, Il Boom (1963) by Vittorio De Sica and C'eravamo tanto amati (1974) by Ettore Scola all stigmatized selfishness and immorality that they believed characterized the miracle's roaring years.

See also

edit- Economic history of Italy

- Economic miracle

- Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale

- Japanese economic miracle

- La Dolce Vita (1960)

- Post–World War II economic expansion

- Spanish miracle

- Wirtschaftswunder

- Years of Lead, the period of unrest following the Italian economic miracle

References

edit- ^ Life, November 24, 1967 (p.48)

- ^ Nicholas Crafts, Gianni Toniolo (1996). Economic growth in Europe since 1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 441. ISBN 0-521-49627-6.

- ^ David Forgacs, Stephen Gundle (2013). Mass culture and Italian society from fascism to the Cold War. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21948-0.

- ^ Italy, a difficult democracy: a survey of Italian politics by Frederic Spotts and Theodor Wieser

- ^ Michael J. Hogan (1987). The Marshall Plan: America, Britain, and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947–1952. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-521-37840-0.

- ^ "2008/107/1 Computer, Programma 101, and documents (3), plastic / metal / paper / electronic components, hardware architect Pier Giorgio Perotto, designed by Mario Bellini, made by Olivetti, Italy, 1965–1971". www.powerhousemuseum.com. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ "Cyber Heroes: Camillo Olivetti". Hive Mind. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Nicholas Crafts, Gianni Toniolo (1996). Economic growth in Europe since 1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 428. ISBN 0-521-49627-6.

- ^ Ennio Di Nolfo (1992). Power in Europe? II: Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy, and the Origins of the EEC 1952–57. Berlin: de Gruyter. p. 198. ISBN 3-11-012158-1.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (July 1, 1963). Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. (eds.). "290 - Remarks at a Dinner Given in His Honor by President Segni". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ Tagliabue, John (11 August 2007). "Italian Pride Is Revived in a Tiny Fiat". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Cappellieri, Alba. "Brionvega. A brief history of the black box". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ "Hollywood in Rome". harpersbazaar.com. 9 December 2019.

- ^ Paul Ginsborg (2003). A history of contemporary Italy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 219. ISBN 1-4039-6153-0.

- ^ Kitty Calavita (2005). Immigrants at the margins. Law, race and exclusion in Southern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0521846633.

- ^ Poverty and Inequality in Common Market Countries edited by Victor George and Roger Lawson

Further reading

edit- Nardozzi, Giangiacomo. "The Italian" Economic Miracle"." Rivista di storia economica (2003) 19#2 pp: 139-180, in English

- Rota, Mauro. "Credit and growth: reconsidering Italian industrial policy during the Golden Age." European Review of Economic History (2013) 17#4 pp: 431–451.

- Tolliday, Steven W. "Introduction: enterprise and state in the Italian'economic miracle'." Enterprise and Society (2000) 1#2 pp: 241–248.