MirrorMask is a 2005 British-American dark fantasy film designed and directed by Dave McKean, and written by Neil Gaiman from a story they developed together. Produced by The Jim Henson Company, the film stars Stephanie Leonidas, Jason Barry, Rob Brydon, and Gina McKee.

| MirrorMask | |

|---|---|

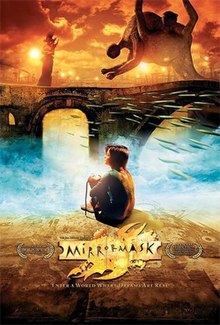

One-sheet promotional poster. | |

| Directed by | Dave McKean |

| Screenplay by | Neil Gaiman |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Simon Moorhead |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Tony Shearn |

| Edited by | Nicolas Gaster |

| Music by | Iain Ballamy |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Samuel Goldwyn Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $973,613[4] |

Gaiman and McKean worked on the film concepts over the course of two weeks at Jim Henson's family's home. Production took seventeen months on a budget of $4 million. Initially intended for the direct-to-video market,[2] MirrorMask premiered at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival before receiving a limited theatrical run in the United States on September 30, 2005. Critical reaction was mixed, with praise for the visuals but criticism towards the story and script.

Plot

editHelena Campbell works alongside her parents Joanne and Morris at their family circus, but desires to join real life. At the next performance, after a heated argument between mother and daughter, Joanne collapses and is taken to the hospital. While Helena stays with her grandmother, she learns that her mother requires an operation, and Helena can only blame herself for the situation.

That night, Helena wakes in a dream-like state and leaves her building to find a trio of performers outside. As they perform for her, a shadow encroaches on the area and two of the performers are consumed by it. The third, a juggler named Valentine, helps to quickly direct Helena to safety via magical flying books. She learns they are in the City of Light, slowly being consumed by shadows, causing its widely varied citizens to flee. Soon, Helena is mistaken for the Princess. She and Valentine are taken to the Prime Minister. He explains that the Princess from the Land of Shadows stole a charm from the White City, leaving their Queen of Light in a state of unnatural sleep and the City vulnerable to the Shadows. Helena notes the resemblance of the Queen and Minister to her mother and father, and offers to help recover the charm along with Valentine. They are unaware their actions are being watched by the Queen of Shadows, who has mistaken Helena for her daughter.

As they strive to stay ahead of the shadows, Helena and Valentine follow clues to the charm, called the "MirrorMask". Helena discovers that by looking through the windows of the buildings, she can see into her bedroom in the real world, through the drawings of windows that she created and hung on the wall of her room. She discovers that a doppelgänger is living there, behaving radically differently from her. The doppelgänger soon becomes aware of her presence in the drawings and begins to destroy them, causing parts of the fantasy world to collapse. Valentine betrays Helena to the Queen of Shadows in exchange for a large reward of jewels. The Queen's servants brainwash Helena into believing that she is the Princess of Shadows. Valentine has a change of heart and returns to the Queen's palace, helping Helena break the spell. They search the Princess' room, and Helena discovers the MirrorMask hidden in the mirror. They flee the castle with the charm.

As they escape to Valentine's flying tower, Helena realizes that her doppelgänger in the real world is the Princess of Shadows, who had used the MirrorMask to step through the windows in Helena's drawings. The Princess destroys the rest of the drawings, preventing Helena from returning, and Helena and Valentine disappear in the collapsed world. The Princess takes the drawings to the roof to disperse the shreds into the wind, but discovers one more drawing Helena had made on the back of the roof door. Helena successfully returns to reality, sending the Princess back to her realm. Simultaneously, the Queen of Light awakens and the two Cities are restored to their natural balance.

Helena is woken on the roof by her father, and they're overjoyed to hear that Joanne's operation is a success. Helena happily returns to work at the circus, where she becomes fascinated by a young man—heavily resembling Valentine—who aspires to be a juggler.

Cast

edit- Stephanie Leonidas as Helena Campbell, a young circus performer and aspiring artist who is drawn into a mysterious world of masked people and monsters shortly after her mother is hospitalized. It is eventually revealed that the world she entered was created through her own drawings that she hung up on the walls of her room. Leonidas stated that she expected that filming would be difficult because most of the scenes were done with one or two other actors just with a bluescreen in the background, but also said that "it all came alive" for them when they started working.[5]

- Leonidas also portrays The Princess, Helena's parallel self and the Queen of Shadows' rebellious daughter. She uses the MirrorMask to switch places with Helena and hides it in her room. After escaping to the "real world", she takes advantage of her new freedom: dressing like a teenage punk, kissing boys, smoking, and arguing with Helena's father.

- Jason Barry as Valentine, a juggler who keeps describing himself as a "very important man". He is Helena's companion in the dream world, although he betrays Helena by handing over to the Queen of Shadows. He regrets this decision, however, and returns to rescue Helena. He is very proud of his tower, though he mentions that he had an argument with it and that they parted ways. As he and Helena are being pursued by the Queen of Shadows, he calls the tower to aid their escape by shouting an apology to it. When Helena reawakens in her world, she meets him again auditioning as a juggler for the circus.

- Rob Brydon as Morris Campbell, Helena's father. A juggler and ringmaster of his family circus, he is a gentle and kind man with an artistic temperament. He is frightened and overwhelmed by his wife's illness. Brydon also plays the Queen of Light's majordomo.

- Gina McKee as Joanne Campbell, Helena's mother. A circus acrobat and ticket-seller, Joanne collapses during a skit and is confined in the hospital shortly after having an argument with Helena. After a successful operation, Joanne recovers and returns to circus life with her family.

- McKee also plays The Queen of Shadows, a possessive mother who treats her daughter like a pet. She mistakes Helena for the Princess who has run away, but when Helena reveals who she is, the Queen does not care as long as she has a daughter.

- McKee also plays The Queen of Light, a kind ruler. She falls into a deep sleep when the MirrorMask is stolen from her, leaving her city vulnerable to the Shadows.

The film also features appearances by Dora Bryan and the voices of Stephen Fry, Lenny Henry, Robert Llewellyn, and others.

Production

editDevelopment

editExecutive producer Michael Polis mentioned that the idea of creating MirrorMask began when The Jim Henson Company and Sony Pictures expressed interest in making a film that would sell as well in video release as Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal based on the two films' consistent DVD sales in 1999. They had considered creating a prequel to Dark Crystal and sequels for Labyrinth, but decided that "it made the most sense to try and create something similar or in the spirit of those films and attribute it as a Jim Henson Company fantasy title."[2]

After being shown a short film directed by McKean, Lisa Henson contacted Gaiman in 2001 about the project, asking if McKean would be interested in directing and if Gaiman was interested in coming up with the story for the film. Gaiman agreed to write for the film if McKean agreed to direct.[2][6]

Production for the film took seventeen months, with a budget of $4 million.[7] Though limited by the $4 million budget, McKean viewed this as a good thing, saying "It's very good to have a box to fight against, and to know where your limitations are, because it immediately implies a certain kind of thing... a certain kind of shape... a certain approach to things."[8]

Setting

editAccording to McKean, the film's setting was originally in London, but that had opted to film it in Brighton at producer Simon Moorhead's suggestion. McKean described Brighton as "more bohemian, so that fits with the whole circus thing, with Helena's family", and that he liked the specific apartment building - Embassy Court - that they used because "it's very distinctive, imposing, it does have this character, but it also represents Helena's collapse and her disintegration into this other world and it's a potent symbol for her mother."[9]

Writing

editMcKean and Gaiman worked on the story and concepts for the film over a span of two weeks in February 2002 at the Henson's family home.[8][10] Gaiman stated that he wanted to do "a sort of Prince and Pauper idea. Something with a girl who was somehow split into two girls who became one at the end." He went on to say that he "had an idea of a girl who was part of a traveling theatre and her mother getting sick and having to go off the road", and mentioned that McKean preferred to have a circus over a theatre "because it was more interesting visually." McKean was the one who came up with the idea of the masks and the two mothers.[7] McKean said that Labyrinth provided something of a starting point for the project, and that he liked the "human element of that film," but that ultimately the story of MirrorMask was something that he and Gaiman came up with on their own.[9] Gaiman wrote the screenplay in February 2002,[11] and said that they always knew that it would be a coming of age story about a girl on a quest, but that later they learned "that it really was just the story of the relationship between a girl and her mother."[12]

Design

editPolis initially spoke to both McKean and Brian Froud, the concept artist for Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal.[2] The initial intention was to have McKean direct the film with Froud doing the designs, but Polis stated that it "made more sense" to have McKean do the designs seeing as he was the one directing the film.[2] Since they had a tight budget, McKean designed creatures who were comparatively simple.[9] He assigned entire sequences rather than tiny pieces to individual artists, so that the young professionals working on the film would have the creative opportunity to make part of it their own.[13] He worked with them very closely in a single room.[9] About the animators, he said that, "All but two were straight from art school and almost all from Bournemouth. We took half the class. They all knew each other already."[14] McKean says that one example of the spirit of the film is that they only had one peach during the filming of the scene where Valentine eats the future fruit.[13] Artist Ian Miller also contributed to the designs of trees and certain other objects in the film, and also provided some of the illustrations pinned to Helena's bedroom wall.[15]

Music

editThe music used in the film was composed by Iain Ballamy, McKean's friend whom he describes as "one of Europe's best sax players" and "a terrific composer." McKean stated that he "wanted a musical landscape that never quite settled on anywhere geographically or time-wise as well." He also noted that Ballamy has composed music for and performed in circuses before, and that "[h]e just seemed to be perfect for it." McKean said that they could not afford to have a full orchestra due to budget constraints, but that they commissioned several of Ballamy's contacts to help record the music. Digital recordings were used with the aid of Ashley Slater, but McKean stated that most of the instruments used were real. Swedish singer Josefine Cronholm provided the vocals for the songs used in the film. The circus band are musicians from Farmers Market.[7] The film's soundtrack, containing thirty tracks of background music and songs used in the film, was released by La-La Land Records in 2005.[16]

Release

editThe film was first screened at a high school, where it got a positive response. The film also received positive reactions when it was screened at the Sundance Film Festival.[11] The film was originally made for a direct-to-video release,[2] but had its limited theatrical release on September 30, 2005, in the United States.

The North American DVD was released on February 14, 2006.[17] The DVD contains additional content such as commentaries, interviews, behind-the-scenes clips, and an art gallery.[18] The film was listed as #31 on the Billboard Top DVD Sales chart the week of March 11, 2006.[19] Neil Gaiman commented that the DVD sold "better than expected" and that it was "gathering an audience".[20]

Reception

editBox office

editThe film earned a total domestic gross of $866,999, earning $126,449 on its opening weekend.[3]

Critical response

editThe film received mixed reactions from critics. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 54% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 89 reviews, with an average rating of 5.80/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "While visually dazzling, there isn't enough story to hang all the fancy effects on."[21] Metacritic gave the film a weighted average score of 55 out of 100 based on 27 reviews.[22]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film two out of four stars, praising the film's visual artistry but stating that there is "no narrative engine to pull us past the visual scenery", and that he "suspected the filmmakers began with a lot of ideas about how the movie should look, but without a clue about pacing, plotting or destination."[23] Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a rating of A−, saying that the film is a "dazzling reverie of a kids-and-adults movie, an unusual collaboration between lord-of-the-cult multimedia artist Dave McKean and king-of-the-comics Neil Gaiman (The Sandman)" and that it "has something to astonish everyone."[24] Stephen Holden of The New York Times described the film's look as "hazy, indistinct, sepia-tinted, overcrowded and flat", and that "its monochromatic panoramas are too busy and flat to yield an illusion of depth or to convey a feeling of characters moving in space." He went on to say that the film is "The embodiment of a cult film, one destined for a rich life on home video".[25] Desson Thomson of The Washington Post described the film as "so single-minded in its reach for fantasy, it becomes the genre's evil opposite: banality."[26]

Accolades

editThe film was nominated for the Golden Groundhog Award for Best Underground Movie,[27] other nominated films were Lexi Alexander's Green Street, Rodrigo García's Nine Lives, the award-winning baseball documentary Up for Grabs and Opie Gets Laid.[28]

Other media

editIn 2005, Tokyopop, in partnership with The Jim Henson Company, announced plans to publish a manga-style comic prequel to the film, which would center around the Princess' escape from the Dark Palace and how she acquired the MirrorMask.[29] The manga was reportedly canceled in 2007.[30]

A children's book based on the film, authored by Gaiman and illustrated by McKean, was published by HarperCollins Children's Books in September 2005.[31] An audiobook based on the children's book has also been released by HarperCollins in December 2005.[32] A book containing the film's complete storyboard and script as well as some photographs and archival text by Gaiman and McKean, titled The Alchemy of MirrorMask, was also published by HarperCollins in November 2005.[33]

The band The Crüxshadows wrote and performed "Wake the White Queen", which retells the story of MirrorMask. This track appears on the Neil Gaiman-inspired compilation album, Where's Neil When You Need Him?

Dark Horse Comics released a number of MirrorMask related merchandise in 2005. Three PVC figure sets, which included three figures per set, were released from May to June 2005. These sets included figures of characters such as Helena, Valentine, the Dark Queen, as well as figures of minor characters like the Librarian and the Small Hairy Guy.[34][35][36] A journal made to look like the Really Useful Book, which provided aid for Helena in the film, was released in July 2005,[37] and a seven-inch tall bust of the Dark Queen was released in August 2005.[38]

References

edit- ^ "Jim Henson Pictures". Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weiland, Jonah (August 6, 2004). "Putting on the "MirrorMask": Executive Producer Michael Polis on the Film". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ a b "MIRRORMASK". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2009-07-25. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ "MirrorMask (2005) - Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ^ Epstein, Daniel Robert. "Stephanie Leonidas of MirrorMask". UGO.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2005. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ Flanagan, Mark (September 9, 2005). "Neil Gaiman Interview (page 2)". About.com. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ a b c Khouri, Andy (September 15, 2005). "The "MirrorMask" Interviews: Neil Gaiman & Dave McKean". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ a b P., Ken (7 Feb 2005). "An Interview with Dave McKean (page 3)". IGN. News Corporation. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ a b c d Holmes, Kevin. "Dave McKean talks to Close-Up Film About MirrorMask". close-upfilm.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ^ Rogers, Troy. "Neil Gaiman Interview". UGO.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2006. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ a b Brevet, Brad (2005-01-31). "INTERVIEW: Neil Gaiman Talks 'MirrorMask' and More". RopeofSilicon.com. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ^ Wilkinson, Amber. "Behind The MirrorMask". Eye For Film. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ^ a b Simon Moorhead et al. (2006). MirrorMask. Bonus Features: Making of MirrorMask (DVD). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.

- ^ Carnevale, Rob. "Mirrormask - Dave McKean interview". IndieLondon.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ^ McKean, Dave; Gaiman, Neil (2006). MirrorMask (DVD commentary). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.

- ^ "MirrorMask". La-La Land Records. Archived from the original on 2009-09-17. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ Swindoll, Jeff (February 13, 2006). "DVD Review: MirrorMask". Monsters and Critics. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ "MirrorMask - About the DVD". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ "Top DVD Sales Mirrormask". Billboard. Retrieved 2009-07-02.[dead link]

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (May 31, 2006). "Gremlin rules". NeilGaiman.com. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ "Mirrormask (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. 30 September 2005. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "MirrorMask Reviews". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 30, 2005). "'MirrorMask' all image, little substance". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (September 28, 2005). "MirrorMask (2005)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (September 30, 2005). "A Teenager's Phantasmagoric Journey to Her Own Identity". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ Thomson, Desson (September 30, 2005). "A Mere Reflection". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ von Busack, Richard (March 8, 2006). "Sunnyvale". Metroactive. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ^ Tyler, Joshua (January 10, 2006). "Shatner Gets His Own Award". Cinema Blend. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ^ "Tokyopop Press Release". 2005-07-19. Archived from the original on 2009-09-12. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ "Ask the Editors: Any news about the Mirrormask manga?". 2007-08-06. Archived from the original on 2009-09-12. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ "MirrorMask (children's edition)". HarperCollinsChildrens.com. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "MirrorMask Unabridged CD". HarperCollins. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "The Alchemy of MirrorMask". HarperCollins. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "MirrorMask PVC Set #1". Dark Horse. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "MirrorMask PVC Set #2". Dark Horse. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "MirrorMask PVC Set #3". Dark Horse. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "DHorse Deluxe Journal: MirrorMask Really Useful Journal". Dark Horse. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "MirrorMask: Dark Queen Bust". Dark Horse. Retrieved 2009-06-11.