Myxomatosis is a disease caused by Myxoma virus, a poxvirus in the genus Leporipoxvirus. The natural hosts are tapeti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis) in South and Central America, and brush rabbits (Sylvilagus bachmani) in North America. The myxoma virus causes only a mild disease in these species, but causes a severe and usually fatal disease in European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), the species of rabbit commonly raised for companionship and as a food source.

| Myxoma virus | |

|---|---|

| |

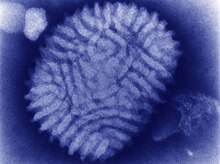

| Myxoma virus (transmission electron microscope) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Nucleocytoviricota |

| Class: | Pokkesviricetes |

| Order: | Chitovirales |

| Family: | Poxviridae |

| Genus: | Leporipoxvirus |

| Species: | Myxoma virus

|

Myxomatosis is an example of what occurs when a virus jumps from a species adapted to the virus to a naive host, and has been extensively studied for this reason.[1] The virus was intentionally introduced in Australia, France, and Chile in the 1950s to control wild European rabbit populations.[2]

Cause

editMyxoma virus is in the genus Leporipoxvirus (family Poxviridae; subfamily Chordopoxvirinae). Like other poxviruses, myxoma viruses are large DNA viruses with linear double-stranded DNA. Virus replication occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell. The natural hosts are tapeti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis) in South and Central America, and brush rabbits (Sylvilagus bachmani) in North America. The myxoma virus causes only a mild disease in these species, with signs limited to the formation of skin nodules.[3]

Myxomatosis is the name of the severe and often fatal disease in European rabbits caused by the myxoma virus. Different strains exist which vary in their virulence. The Californian strain, which is endemic to the west coast of the United States and Baja in Mexico, is the most virulent, with reported case fatality rates approaching 100%.[4] The South American strain, present in South America and Central America, is slightly less virulent, with reported case fatality rates of 99.8%. Strains present in Europe and Australia were originally introduced from South America but have become attenuated, with reported case fatality rates of 50–95%. While wild rabbits in Europe and Australia have developed some immunity to the virus, this is not generally true of pet rabbits.[5]

Transmission

editMyxomatosis is transmitted primarily by insects. The myxoma virus does not replicate in these arthropod hosts, but is physically carried by biting arthropods from one rabbit to another. In North America mosquitoes are the primary mode of viral transmission, and multiple species of mosquito can carry the virus.[6][7][8][9] In Europe the rabbit flea is the primary means of transmission.[10] Transmission via the bites of flies, lice, and mites have also been documented.[11][10] Outbreaks have a seasonal nature and are most likely to occur between August and November, but cases can occur year round.[12][13] Seasonality is driven by the availability of arthropod vectors and the proximity of infected wild rabbits.[14]

The myxoma virus can also be transmitted by direct contact. Infected rabbits shed the virus in ocular and nasal secretions and from areas of eroded skin. The virus may also be present in semen and genital secretions. Poxviruses are fairly stable in the environment and can be spread by contaminated objects such as water bottles, feeders, caging, or people's hands.[14] They are resistant to drying but are sensitive to some disinfectants.[15]

Pathophysiology

editA laboratory study in which European rabbits received intradermal injections of a South American strain of the myxoma virus demonstrated the following progression of disease. Initially the virus multiplied in the skin at the site of inoculation. Approximately two days following inoculation the virus was found in nearby lymph nodes, and at three days it was found in the bloodstream and abdominal organs. At approximately four days the virus was isolated from non-inoculated skin as well as from the testes. Slight thickening of the eyelids and the presence of virus in conjunctival fluid was detectable on day five. Testicular engorgement was noticed on day six.[16]

Clinical presentation: South American strains of myxomatosis

editThe clinical signs of myxomatosis depend on the strain of virus, the route of inoculation, and the immune status of the host. Signs of the classic nodular form of the disease include a subcutaneous mass at the site of inoculation, swelling and edema of the eyelids and genitals, a milky or purulent ocular discharge, fever, lethargy, depression, and anorexia.[14]

According to Meredith (2013), the typical time course of the disease is as follows:[3]

| Days after infection | Clinical signs |

|---|---|

| 2–4 | Swelling at site of infection |

| 4 | Fever |

| 6 | Swelling of eyelids, face, base of ears, and anogenital area |

| 6 | Secondary skin lesions, including red pinpoint lesions on eyelids and raised masses on body |

| 6–8 | Clear ocular and nasal discharge that becomes mucopurulent and crusting |

| 7–8 | Respiratory distress |

| 8–9 | Hypothermia |

| 10 | Complete closure of eyelids due to swelling |

| 10–12 | Death |

In peracute disease with a highly virulent strain, death may occur within 5 to 6 days of infection with minimal clinical signs other than the conjunctivitis. Death usually occurs between days 10 and 12.

In rabbits infected with attenuated, less virulent strains of the virus, the lesions seen are more variable and generally milder, and the time course is delayed and prolonged. Many rabbits will survive and the cutaneous lesions gradually scab and fall off, leaving scarring. A milder form of the disease is also seen in previously vaccinated domestic rabbits that have partial immunity. Vaccinated rabbits often present with localized scabbed lesions, frequently on the bridge of the nose and around the eyes, or multiple cutaneous masses over the body. They are often still bright and alert, and survive with nursing care.[3]

Respiratory signs are a common finding in rabbits that survive the first stages of myxomatosis. Mucopurulent nasal discharge occurs, leading to gasping and stertorous respiration with extension of the head and neck. Secondary bacterial pneumonia occurs in many cases. Chronic respiratory disease, such as nasal discharge, is common in surviving rabbits. Even in apparently recovered rabbits, it is not unusual to find lung lobes filled with fluid rather than air at necropsy.[14]

Since the 1970s an "amyxomatous" form of the disease has been reported in Europe which lacks the cutaneous nodules typical of myxomatosis. This form is clinically milder and generally nonlethal. Respiratory signs, including clear or purulent nasal discharge, predominate. Perineal edema, swollen eyelids, and purulent blepharoconjunctivitis are generally still present. This form has been observed in wild rabbits, but is significant mainly in farmed rabbits.[3]

Clinical presentation: North American strains of myxomatosis

editThe distribution of Myxomatosis in North America is limited to the brush rabbit’s native habitat, which extends from the Columbia River in Oregon to the north, the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains to the East, and the tip of the Baja California peninsula to the south.[3] The brush rabbit is the sole carrier of myxoma virus in North American because other native lagomorphs, including cottontail rabbits and hares, are incapable of transmitting the disease.[4][1] Clinical signs of myxomatosis depend on the strain of virus, the route of inoculation, and the immune status of the host. Cases of myxomatosis in northern California, southern California, Oregon, and Mexico are caused by different strains of myxoma virus, and symptoms vary. All North American strains are highly virulent, with close to 100% case fatality rates.

California

editA 1931 paper reported twelve cases of myxomatosis from Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Diego counties of California. Affected rabbits developed mucopurulent conjunctivitis and swelling of the nose, lips, ears, and external genitalia. Rabbits that survived for over a week developed cutaneous nodules on the face.[17]

A 2024 study found that myxomatosis caused by the MSW strain (California/San Francisco 1950) of the myxoma virus occurs regularly in the greater San Jose and Santa Cruz regions of California. Common physical examination findings included swollen eyelids, swollen genitals, fever, and lethargy. Swollen lips and ears and subcutaneous edema also occurred in some rabbits. Domesticated rabbits that spent time outdoors were at greater risk of acquiring the disease, and most of the cases occurred between August and October. It was postulated that that the number of cases brought to veterinarians underestimated the total number of cases, as sudden death was sometimes the first sign noted.[13]

Oregon

editA 1977 report from western Oregon described several cases of myxomatosis. The most common clinical signs observed were inflammation and swelling of the eyelids, conjunctiva, and anogenital region. Lethargy, fever, and anorexia were also observed. A single rabbit with confirmed myxomatosis eventually recovered.[18]

A 2003 report of a myxomatosis outbreak in western Oregon reported sudden death as a common finding. Also noted were lethargy, swollen eyelids, and swollen genital regions.[19]

Baja California

editA 2000 report from the Baja Peninsula in Mexico described two outbreaks of myxomatosis in 1993. Affected domestic rabbits developed skin nodules and respiratory symptoms.[20]

Diagnosis

editBecause the clinical signs of myxomatosis are distinctive and nearly pathognomonic, initial diagnosis is largely based on physical exam findings.[21][22][23] If a rabbit dies without exhibiting the classic signs of myxomatosis, or if further confirmation is desired, a number of laboratory tests are available.

Tissues from rabbits suffering from myxomatosis show a number of changes on histopathology. Affected skin and mucous membranes typically show undifferentiated mesenchymal cells within a matrix of mucin, inflammatory cells, edema, and intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies. Spleen and lymph nodes are often affected by lymphoid depletion. Necrotizing appendicitis and secondary infections with gram-negative bacteria have also been described.[13][18][19]

The development of molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays has created faster and more accurate methods of myxoma virus identification.[24] PCR can be used on swabs, fresh tissue samples, and on paraffin-embedded tissue samples to confirm the presence of the myxoma virus and as well as to identify the viral strain.[25]

Other Testing

editOther means of diagnosing myxomatosis include immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and virus isolation. Immunohistochemistry can demonstrate the presence of myxoma virus particles in different cells and tissues of the body.[13][19] Negative-stain electron microscopic examination can be used to identify the presence of a poxvirus, although it does not allow specific verification of virus species or variants.[24] Virus isolation remains the "gold standard" against which other methods of virus detection are compared. Theoretically at least, a single viable virus present in a specimen can be grown in cultured cells, thus expanding it to produce enough material to permit further detailed characterization.[26]

Treatment

editAt present, no specific treatment exists for myxomatosis. Given that the mortality rate of North American strains of myxomatosis nears 100%, euthanasia is often recommended in the United States.[13] In other countries where less virulent strains are present and vaccines against the disease are available, supportive care may help rabbits to survive the infection. If treatment is attempted then careful monitoring is necessary to avoid prolonging suffering. Cessation of food and water intake, ongoing severe weight loss, or rectal temperatures below 37 °C (98.6 °F) are reasons to consider euthanasia.[14][27]

Prevention

editVaccination

editVaccines against myxomatosis are available in some countries. All are modified live vaccines based either on attenuated myxoma virus strains or on the closely related Shope fibroma virus, which provides cross-immunity. It is recommended that all rabbits in areas of the world where myxomatosis is endemic be routinely vaccinated, even if kept indoors, because of the ability of the virus to be carried inside by vectors or fomites. In group situations where rabbits are not routinely vaccinated, vaccination in the face of an outbreak is beneficial in limiting morbidity and mortality.[3] The vaccine does not provide 100% protection,[14] so it is still important to prevent contact with wild rabbits and insect vectors. Myxomatosis vaccines must be boostered regularly to remain effective, and annual vaccinations are usually recommended.[3]

In Europe and the United Kingdom a bivalent vectored vaccine called Nobivac Myxo-RHD[28] is available that protects against both myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease. This vaccine is licensed for immunization of rabbits 5 weeks of age or older, with onset of immunity taking approximately 3 weeks. Protection against myxomatosis and rabbit hemorrhagic disease has a duration of immunity for 12 months, and annual vaccination is recommended to ensure continued protection. The vaccine has been shown to reduce mortality and clinical signs of myxomatosis.[29]

Vaccination against myxomatosis is currently prohibited in Australia due to concerns that the vaccine virus could spread to wild rabbits and increase their immunity to myxomatosis. As feral rabbits in Australia already cause a great deal of environmental damage, this concern is taken seriously by the government.[30] Many pet rabbits in Australia continue to die from myxomatosis due to their lack of immunity.[31] There is at least one campaign to allow the vaccine for domestic pets.[32] The Australian Veterinary Association supports the introduction of a safe and effective myxomatosis vaccine for pet rabbits,[33] and the RSPCA of Australia has repeatedly called for a review of available myxoma virus vaccines and a scientific assessment of their likely impacts in the Australian setting.[34]

Although myxomatosis is endemic in parts of Mexico and the United States, there is no commercially available vaccine in either of these countries.

Other preventive measures

editIn locations where myxomatosis is endemic but no vaccine is available, preventing exposure to the myxoma virus is of vital importance. The risk of a pet contracting myxomatosis can be reduced by preventing contact with wild rabbits, and by keeping rabbits indoors (preferred) or behind screens to prevent mosquito exposure. Using rabbit-safe medications to treat and prevent fleas, lice, and mites is also warranted. New rabbits that could have been exposed to the virus should be quarantined for 14 days before being introduced to current pets.

Any rabbit suspected of having myxomatosis should be immediately isolated, and all rabbits in the area moved indoors. To prevent the virus from spreading further any cages and cage furnishings that have come into contact with infected rabbits should be disinfected, and owners should disinfect their hands between rabbits. Poxviruses are stable in the environment and can be spread by fomites but are highly sensitive to chemical disinfection; bleach, ammonia, and alcohol can all be used to deactivate myxoma virus.[35]

Reporting

editMyxomatosis is a reportable disease in California, the United States, and in Mexico.[36][37][38] Veterinarians and pet owners who see this disease are encouraged to report all cases to the relevant agencies. Without accurate data on myxomatosis in North America, vaccine manufacturers will underestimate the need for a vaccine and be reluctant to produce one.

Use as a population control agent

editMyxoma virus was the first virus intentionally introduced into the wild with the purpose of eradicating a vertebrate pest, namely the European rabbit in Australia and Europe. The long-term failure of this strategy has been due to natural selective pressures on both the rabbit and virus populations, which resulted in the emergence of myxomatosis-resistant animals and attenuated virus variants. The process is regarded as a classical example of host–pathogen coevolution following cross-species transmission of a pathogen.[39]

Australia

editEuropean rabbits were brought to Australia in 1788 by early English settlers. Initially used as a food source, they later became feral and their numbers soared. In November 1937, the Australian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research used Wardang Island to conduct its first field trials of myxomatosis, which established the methodology for the successful release of the myxoma virus throughout the country.[40]

In 1950, the SLS strain of myxoma virus from the South American tapeti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis) was released in Australia as a biological control agent against feral rabbits. The virus was at first highly lethal, with an estimated case fatality rate of close to 99.8%. Within a few years, however, this strain was replaced by less virulent ones, which permitted longer survival of infected rabbits and enhanced disease transmission. The virus created strong selection pressure for the evolution of rabbits resistant to myxomatosis. As rabbits became more resistant the viral strains responded by becoming less virulent.[5] Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus has also been used to control wild rabbit populations in Australia since 1995.[41]

Europe

editIn June 1952, Paul-Félix Armand-Delille, the owner of an estate in northwestern France, inoculated two wild rabbits with the Lausanne strain of myxoma virus.[42] His intention was to only eradicate rabbits on his property and town, but the disease quickly spread through Western Europe, Ireland and the United Kingdom.[1] Some dissemination of the virus clearly appeared deliberate, such as the introduction into Britain in 1953 and the introduction into Ireland in 1954.[43] Unlike in Australia, however, strenuous efforts were made to stop the spread in Europe. These efforts proved in vain. According to estimates, the wild rabbit population in the United Kingdom fell by 99%, in France by 90% to 95%, and in Spain by 95%. This in turn drove specialized rabbit predators, such as the Iberian lynx and the Spanish imperial eagle, to the brink of extinction.[44][45]

Myxomatosis not only decreased the wild rabbit population and the population of its natural predators, but also had significant impacts on the large rabbit-farming industry, which produced domestic rabbits for meat and fur.[46] The Lausanne strain of the myxoma virus causes the formation of large purple skin-nodules, a sign not seen in other strains. As happened in Australia, the virus has generally become less virulent and the wild rabbit populations more resistant subsequently.[1]

New Zealand

editThe introduction of myxomatosis into New Zealand in 1952 to control a burgeoning rabbit problem failed for lack of a vector.[47]

South America

editTwo pairs of European rabbits set free in 1936 at Punta Santa Maria resulted in an infestation that spread over the northern half of Tierra del Fuego. More rabbits were introduced in 1950 near Ushuaia by the Argentinian Navy and a private rabbit farmer. The rabbits quickly became pests, riddling the ground with holes and leaving it bare of grass. By 1953 the rabbit population numbered about 30 million. In 1954 Chilean authorities introduced a Brazilian strain of myxoma virus to Tierra del Fuego, which succeeded in bringing rabbits to very low population levels.[48]

Use as an evolutionary model

editGiven the importance of viral evolution to disease emergence, pathogenesis, drug resistance, and vaccine efficacy, it has been well studied by theoreticians and experimentalists. The introductions of myxoma virus into European rabbit populations in Australia and France created natural experiments in virulence evolution.[49] While initial viral strains were highly virulent, attenuated strains were soon recovered from the field. These attenuated strains, which allowed rabbits to survive longer, came to dominate because they were more readily transmitted. As the complete genome sequences of multiple myxoma strains have been published, scientists have been able to pinpoint exactly which genes are responsible for the changes in the myxoma virus's virulence and behavior.[50]

However, the evolution of the disease has proved to be increasingly complex and unpredictable, both among various strains of host, and among strains of the virus. Both in modes of resistance and of virulence, and in all countries in which the virus has been introduced for control of feral rabbits, the hosts and the pathogens have continually adapted in various ways to evolutionary challenges. Although current strains of myxomatosis do not provide sufficient control on their own, the disease remains a significant ecological factor in rabbit control, both in Australia and in other countries. For example, in spite of long-term concern in Australia especially, where the initial virulence of myxomatosis declined after a few decades in the field, rabbit evolution of resistance to the disease has not gone unchallenged. For some recent strains of the virus, as a case in point, selection for reduced inflammation prolongs virus replication, which enhances transmission and reduces suppression of the virus by the host's fever; it also may cause immunosuppression, which favors high virulence.[51] Studies continue, both in the contexts of rabbit control, and of the relevant evolutionary principles.

In culture

editMyxomatosis is referred to as "the white blindness" by the rabbit characters of the novel Watership Down (1972) by Richard Adams, and in the story a rabbit chief had driven out all rabbits who seemed to be afflicted. In one of the novel's folk tales about the rabbit hero El-ahrairah, the transmission of the disease is explained to him by the lord of the rabbit underworld, the Black Rabbit of Inle ("it is carried by the fleas in rabbits' ears; they pass from the ears of a sick rabbit to those of his companions").[52]

The sixth album of British band Radiohead, Hail to the Thief, contains a song "Myxomatosis". The disease is used as analogy to the journalist attention the band has. Thom Yorke has said:

"I remember my parents pointing out all these dead rabbits on the road when I was a kid. I didn’t know that much about the virus, or even how to spell it, but I loved the word. I loved the way it sounded."[53]

References

edit- ^ a b c Kerr, P; Liu, J; Cattadori, I; Ghedin, E; Read, A; Holmes, E (2015). "Myxoma Virus and the Leporipoxviruses: An Evolutionary Paradigm". Viruses. 7 (3): 1020–1061. doi:10.3390/v7031020. PMC 4379559. PMID 25757062.

- ^ Correa-Cuadros, JP; Flores-Benner, G; Muñoz-Rodríguez, MA; Briceño, C; Díaz, M; Strive, T; Vásquez, F; Jaksic, FM (2023). "History, control, epidemiology, ecology, and economy of the invasion of European rabbits in Chile: a comparison with Australia". Biological Invasions. 25 (2): 309–338. Bibcode:2023BiInv..25..309C. doi:10.1007/s10530-022-02915-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Meredith, A (2013). "Viral skin diseases of the rabbit". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (3): 705–714. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.05.010. PMID 24018033.

- ^ Silvers, L; Inglis, B; Labudovic, A; Janssens, PA; van Leeuwen, BH; Kerr, PJ (2006). "Virulence and pathogenesis of the MSW and MSD strains of Californian myxoma virus in European rabbits with genetic resistance to myxomatosis compared to rabbits with no genetic resistance". Virology. 348 (1): 72–83. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.007. PMID 16442580.

- ^ a b Kerr, PJ; Cattadori, IM; Rogers, MB; Fitch, A; Geber, A; Liu, J; Sim, DG; Boag, B; Eden, JS; Ghedin, E; Read, AF; Holmes, EC (2017). "Genomic and phenotypic characterization of myxoma virus from Great Britain reveals multiple evolutionary pathways distinct from those in Australia". PLOS Pathogens. 13 (3): e1006252. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006252. PMC 5349684. PMID 28253375.

- ^ Grodhaus, G; Regnery, DC; Marshall, ID (1963). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California. II. The experimental transmission of myxomatosis in brush rabbits (Sylvilagus bachmani) by several species of mosquitoes". Am J Hyg. 77: 205–212. PMID 13950625.

- ^ Marshall, ID; Regnery, DC; Grodhaus, G (1963). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California I. Observations on two outbreaks of myxomatosis in coastal California and the recovery of myxoma virus from a brush rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani)". American Journal of Epidemiology. 77 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120310.

- ^ Regnery, DC; Marshall, ID (1971). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California. IV. The susceptibility of six leporid species to Californian myxoma virus and the relative infectivity of their tumors for mosquitoes". American Journal of Epidemiology. 94 (5): 508–513. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121348. PMID 5166039.

- ^ Regnery, DC; Miller, JH (1972). "A myxoma virus epizootic in a brush rabbit population". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 8 (4): 327–331. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-8.4.327. PMID 4634525.

- ^ a b Ross, J; Tittensor, AM; Fox, AP; Sanders, MF (1989). "Myxomatosis in farmland rabbit populations in England and Wales". Epidemiology and Infection. 103 (2): 333–357. doi:10.1017/s0950268800030703. PMC 2249516. PMID 2806418.

- ^ Bertagnoli, S; Marchandeau, S (2015). "Myxomatosis". Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 34 (2): 539–556. doi:10.20506/rst.34.2.2378. PMID 26601455.

- ^ Farrell, S; Noble, PJM; Pinchbeck, GL; Brant, B; Caravaggi, A; Singleton, DA; Radford, AD (2020). "Seasonality and risk factors for myxomatosis in pet rabbits in Great Britain". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 176: 104924. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.104924. PMID 32114004.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, HS; Biswell, E; Kiupel, M; Ossiboff, RJ; Brust, K (2024). "Epidemiologic, clinicopathologic, and diagnostic findings in pet rabbits with myxomatosis caused by the California MSW strain of myxoma virus: 11 cases (2022–2023)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 262 (9): 1–11. doi:10.2460/javma.24.02.0139. PMID 38788762.

- ^ a b c d e f Kerr, P (2013). "Viral Infections of Rabbits". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (2): 437–468. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.02.002. PMC 7110462. PMID 23642871.

- ^ "Disinfection". The Center for Food Security and Public Health. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Fenner, F; Woodroofe, GM (1953). "The pathogenesis of infectious myxomatosis: the mechanism of infection and the immunological response in the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)". The British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 34 (4): 400–411. PMC 2073564. PMID 13093911.

- ^ Kessel, JF; Prouty, CC; Meyer, JW (1931). "Occurrence of infectious myxomatosis in southern California". Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 28 (4): 413–414. doi:10.3181/00379727-28-5342.

- ^ a b Patton, NM; Holmes, HT (1977). "Myxomatosis in domestic rabbits in Oregon". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 171 (6): 560–562. PMID 914688.

- ^ a b c Löhr, CV; Kiupel, M; Bildfell, RJ (2005). "Outbreak of myxomatosis in domestic rabbits in Oregon: pathology and detection of viral DNA and protein". Veterinary Pathology. 42 (5): 680–729. doi:10.1177/030098580504200501.

- ^ Licón Luna, RM (2000). "First report of myxomatosis in Mexico". J Wildl Dis. 36 (3): 580–583. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-36.3.580. PMID 10941750.

- ^ Kerr P (2013). "Myxomatosis". In Mayer, J; Donnelly, TM (eds.). Clinical Veterinary Advisor: Birds and Exotic Pets. Elsevier Saunders. pp. 398–401.

- ^ Smith MV (2023). "Urogenital diseases". In Smith, MV (ed.). Textbook of Rabbit Medicine (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 314–331.

- ^ Girolamo ND; Selleri P (2021). "Disorders of the urinary and reproductive systems". In Quesenberry, KE; Orcutt, CJ; Mans, C; Carpenter, JW (eds.). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents (4th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 201–219.

- ^ a b MacLachlan, J (2017). Fenner's Veterinary Virology, 5th Edition. Elsevier. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ^ Albini, S; Sigrist, B; Güttinger, R; Schelling, C; Hoop, RK; Vögtlin, A (2012). "Development and validation of a Myxoma virus real-time polymerase chain reaction assay". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 24 (1): 135–137. doi:10.1177/1040638711425946. PMID 22362943.

- ^ MacLachlan, J (2017). Fenner's Veterinary Virology, 5th Edition. Elsevier. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ^ Wolfe, AM; Rahman, M; McFadden, DG; Bartee, EC (2018). "Refinement and successful implementation of a scoring system for myxomatosis in a susceptible rabbit ( Oryctolagus cuniculus ) Model". Comparative Medicine. 68 (4): 280–285. doi:10.30802/AALAS-CM-18-000024. PMC 6103426. PMID 30017020.

- ^ "Nobivac Myxo RHD". MSD Animal Health. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Nobivac Myxo RHD Data Sheet". European Medicine Agency. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "A Statement from the Chief Veterinary Officer (Australia) on myxomatosis vaccine availability in Australia". Australian Government Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "The Rabbit Sanctuary Myxomatosis Hotline". Myxomatosis. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Myxo Campaign". Myxomatosis. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Myxomatosis vaccination of pet rabbits". Australian Veterinary Association. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Why can't I vaccinate my rabbit against Myxomatosis?". Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Delhon, Gustavo (2022). "Poxviridae". Veterinary Microbiology. pp. 522–532. doi:10.1002/9781119650836.ch53. ISBN 978-1-119-65075-1.

- ^ "List of Reportable Conditions for Animals and Animal Products" (PDF). Animal Health Branch. California Department of Food and Agriculture. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Reportable Diseases, Infections, and Infestations List" (PDF). National Animal Health Reporting System. USDA Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Myxomatosis" (PDF). General Directorate of Animal Health, Mexico. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ MacLachlan, J (2017). Fenner's Veterinary Virology, 5th Edition. Elsevier. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ^ "Rabbits around a waterhole at the enclosed trial site at Wardang Island, 1938". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Mahar JE, Read AJ, Gu X, Urakova N, Mourant R, Piper M, Haboury S, Holmes EC, Strive T, Hall RN (January 2018). "Detection and Circulation of a Novel Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus in Australia". Emerg Infect Dis. 24 (1): 22–31. doi:10.3201/eid2401.170412. PMC 5749467. PMID 29260677.

- ^ Davis, J. "Darwin's rabbit is revealing how the animals became immune to myxomatosis". Natural History Museum. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Bartrip, P (2008). Myxomatosis: A History of Pest Control and the Rabbit. London, UK: Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-1845115722.

- ^ Gil-Sánchez, JM; McCain, EB (2011). "Former range and decline of the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) reconstructed using verified records". Journal of Mammalogy. 92 (5): 1081–1090. doi:10.1644/10-MAMM-A-381.1.

- ^ Sánchez, B. "Action plan for the Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti) in the European Union" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Cadogan, S (23 March 2017). "How a thriving food industry faded away to nothing in the 1960s". The Irish Examiner. Cork. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Gumbrell, RC (1986). "Myxomatosis and rabbit control in New Zealand". New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 34 (4): 54–55. doi:10.1080/00480169.1986.35282. PMID 16031265.

- ^ Jaksic, F (1983). "Rabbit and Fox Introductions in Tierra del Fuego: History and Assessment of the Attempts at Biological Control of the Rabbit Infestation". Biological Conservation. 26 (4): 369–370. Bibcode:1983BCons..26..367J. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(83)90097-6.

- ^ Bull, JJ; Lauring, AS (2014). "Theory and Empiricism in Virulence Evolution". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (10): e1004387. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004387. PMC 4207818. PMID 25340792.

- ^ Burgess, HM; Mohr, I (2016). "Evolutionary clash between myxoma virus and rabbit PKR in Australia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (15): 3912–3914. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.3912B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1602063113. PMC 4839419. PMID 27035991.

- ^ Kerr, PJ; Cattadori, IM; Sim, D; Liu, J; Holmes, EC; Read, AF (2022). "Divergent Evolutionary Pathways of Myxoma Virus in Australia: Virulence Phenotypes in Susceptible and Partially Resistant Rabbits Indicate Possible Selection for Transmissibility". Journal of Virology. 96 (20): e0088622. doi:10.1128/jvi.00886-22. PMC 9599488. PMID 36197107.

- ^ Cassidy, A (2019). Vermin, Victims and Disease: British Debates Over Bovine Tuberculosis and Badgers. Springer Nature. p. 178. ISBN 9783030191863.

- ^ "Myxomatosis". citizeninsane.eu. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

Further reading

edit- Deane, C.D. (1955). "Note on myxomatosis in hares". Bulletin of the Mammal Society of the British Isles. 3: 20. OCLC 1224626693.

- Fenner, Frank; Ratcliffe, F.N. (1965). Myxomatosis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521049917.