Mnajdra (Maltese: L-Imnajdra) is a megalithic temple complex found on the southern coast of the Mediterranean island of Malta. Mnajdra is approximately 497 metres (544 yd) from the Ħaġar Qim megalithic complex. Mnajdra was built around the fourth millennium BCE; the Megalithic Temples of Malta are among the most ancient religious sites on Earth,[1] described by the World Heritage Sites committee as "unique architectural masterpieces."[2] In 1992 UNESCO recognized the Mnajdra complex and four other Maltese megalithic structures as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[3] In 2009, work was completed on a protective tent.[4]

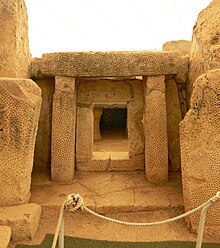

Niche at the Mnajdra South Temple | |

| Location | Qrendi, Malta |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°49′36″N 14°26′11″E / 35.82667°N 14.43639°E |

| Type | Temple |

| History | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Founded | c.3600 BC–c.3200 BC |

| Periods | Ġgantija phase Tarxien phase |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1840–1954 |

| Archaeologists | J. G. Vance Themistocles Zammit John Davies Evans |

| Condition | Well-preserved ruins |

| Ownership | Government of Malta |

| Management | Heritage Malta |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Heritage Malta |

| Part of | Megalithic Temples of Malta |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 132ter-003 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

| Extensions | 1992, 2015 |

| Area | 0.563 ha (60,600 sq ft) |

Design

editMnajdra is made of coralline limestone, which is much harder than the soft globigerina limestone of Ħaġar Qim. The main structural systems used in the temples are corbelling with smaller stones, and post and lintel construction using large slabs of limestone.

The cloverleaf plan of Mnajdra appears more regular than that of Ħagar Qim, and seems reminiscent of the earlier complex at Ggantija. The prehistoric structure consists of three temples, conjoined, but not connected: the upper, middle, and lower.[5][6]

The upper temple is the oldest structure in the Mnajdra complex and dates to the Ġgantija phase (3600-3200 BC).[7] It is a three-apse building, the central apse opening blocked by a low screen wall. The pillar-stones were decorated with pitmarks drilled in horizontal rows on the inner surface.[8]

The middle temple was built (or possibly rebuilt) in the late Tarxien phase (3150 – 2500 BC), the main central doorway of which is formed by a hole cut into a large piece of limestone set upright, a type of construction typical of other megalithic doorways in Malta. This temple appears originally to have had a vaulted ceiling, but only the base of the ceiling now remain on top of the walls [9] and, in fact, is the most recent structure. It is formed of slabs topped by horizontal courses.

The lowest temple, built in the early Tarxien phase, is the most impressive and possibly the best example of Maltese megalithic architecture. It has a large forecourt containing stone benches, an entrance passage covered by horizontal slabs, one of which has survived, and the remains of a possibly domed roof.[10] The temple is decorated with spiral carvings and indentations, and pierced by windows, some into smaller rooms and one onto an arrangement of stones.[7]

Functions

editThe lowest temple is astronomically aligned and thus was probably used as an astronomical observation and/or calendrical site.[11] On the vernal and the autumnal equinox sunlight passes through the main doorway and lights up the major axis. On the solstices sunlight illuminates the edges of megaliths to the left and right of this doorway.[12]

Although there are no written records to indicate the purpose of these structures, archaeologists have inferred their use from ceremonial objects found within them: sacrificial flint knives and rope holes that were possibly used to constrain animals for sacrifice (since various animal bones were found).[citation needed] These structures were not used as tombs since no human remains were found.[13] The temples contain furniture such as stone benches and tables that give clues to their use. Many artifacts were recovered from within the temples suggesting that these temples were used for religious purposes, perhaps to heal illness and/or to promote fertility.[11]

Calendar stone

editOne of the stones displays a lot of drilled holes arranged in different right-aligned rows that can be linked to several periods determined by the moon.[14]

| Row | Number of holes | Possible use |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | For the 19 years of the Metonic cycle (235 synodic, 255 draconic, 254 siderial month respectively 6940 days). After this period the moon has the same lunar phase and the same ecliptic latitude and the same ecliptic longitude (eg in the Golden Gate of the Ekliptic or in the equinox). |

| 2 | 16 (right) | For the 16 days from old moon (still visible) until full moon and the 13 days from full moon until next old moon, together 29 days, the number of full days within a synodic month (29.5 days). After this period the moon has the same lunar phase again. |

| 13 (left above) | ||

| 3 | 3 + 4 (right) = 7 |

For the 7 full days of a moon quarter (7.4 days) respectively of a week. |

| 3 (left) | For the 3 already completed moon quarters within the current month. | |

| 4 | 25 | For the 25 waxing or waning moons (each 14.8 days) within a tropical year (365.2 days). |

| 5 | 11 | For the 11 additional days in a tropical year (365.2 days) in comparison to twelve synodic month (354.4 days). |

| 6 | 24 + 1 = 25 |

For the 24 waxing respectively waning moons within twelve synodic month (354.4 days) plus an incomplete month until the end of the appropriate tropical year (365.2 days). |

| 7 | 53 | For the 53 weeks within a tropical year (365.2 days) respectively from a heliacal ascent or descent of the Pleiades (or stars) to the next one. |

Excavations and recent history

editThe excavations of the Mnajdra temples were performed under the direction of J.G. Vance in 1840, one year after the discovery of Ħagar Qim.[8] In 1871, James Fergusson designed the first plan of the megalithic structure. The plan was quite inaccurate and hence in 1901, Albert Mayr made the first accurate plan which was based on his findings.[15] In 1910, Thomas Ashby performed further investigations which resulted in the collection of the important archaeological material. Further excavations were performed in December 1949, in which two small statues, two large bowls, tools and one large spherical stone, which was probably used to move the temple's large stones, were discovered.[15]

The temple was included on the Antiquities List of 1925.[16]

Mnajdra was vandalized on 13 April 2001, when at least three people armed with crowbars toppled or broke about 60 megaliths, and inscribed graffiti on them. The attack was called "the worst act of vandalism ever committed on the island of Malta" by UNESCO.[17] The damage to the temples was initially considered irreparable,[18] but they were restored using new techniques making it difficult to tell where the megaliths had been damaged. The temples were reopened to the public in 2002.[19]

The 1, 2 and 5 cent Maltese euro coins, minted since 2008, bear a representation of the Mnajdra temples on their obverse side.

A protective shelter was constructed around Mnajdra (along with Ħaġar Qim) in 2009.

Contemporary interpretations

editAnthropologist Kathryn Rountree has explored how "Malta’s neolithic temples", including Ġgantija, "have been interpreted, contested and appropriated by different local and foreign interest groups: those working in the tourist industry, intellectuals and Maltese nationalists, hunters, archaeologists, artists, and participants in the global Goddess movement."[20]

One source from the early years of the twenty-first century speculates that the clover-shape of Mnajdra (presumably the Upper Temple) may represent "the present, past and future (or birth, life and death)", while the solar alignment could mean that "the Sun's Male-energy is also given an honored place in these temples", and that "mother earth was represented by statuettes while father sun was venerated through this temple alignment."[21]

Gallery

edit-

A total view of the structure

-

Ruins of the upper (oldest) temple

-

An important graffito representing a roofed megalithic temple found in Mnajdra

-

Solar angles

-

Map of the Mnajdra temple

-

Protective tent around the site

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Malta Temples and The OTS Foundation". Otsf.org. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ from the Reports of the 4th (1980) and the 16th (1992) Sessions of the Committee

- ^ "Megalithic Temples of Malta - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Prehistoric temples get futuristic roof". Times of Malta. 7 April 2009. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^ Gunther, Michael D. "Plan Of The Temple Complex At Mnajdra". art-and-archaeology.com.

- ^ "Mnajdra Temples, Malta". Sacred-destinations.com. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Heritage Malta". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Places of Interest - Mnajdra". Maltavoyager.com. 4 March 1927. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands" (PDF). Government of Malta. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra (2)". Beautytruegood.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Malta". Sacredsites.com. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Equinox at Mnajdra Temples » Chris and Marika's Online Journal". Chrisf.com.au. 22 September 2004. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Hypogeum, Tarxien & Malta as tip of Atlantis". Carnaval.com. 22 June 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Der Kalenderstein vom Tempel Mnajdra. Wikibook Die Himmelstafel von Tal-Qadi. Retrieved 2020-08-16

- ^ a b Alfie Guillaumier, Bliet u Rhula Maltin, Malta 1972

- ^ "Protection of Antiquities Regulations 21st November, 1932 Government Notice 402 of 1932, as Amended by Government Notices 127 of 1935 and 338 of 1939". Malta Environment and Planning Authority. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Director-General shocked by vandalism of megalithic Mnajdra Temple in Malta". UNESCO. 18 April 2001. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "Vandals cause 'irreparable' damage to Mnajdra temple". The Megalithic Portal. 16 April 2001. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Massa, Ariadne (11 April 2002). "Recent technique used in restoring Mnajdra temples". Times of Malta. MaltaMigration.com. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Rountree, Kathryn (2002). "Re-inventing Malta's neolithic temples: Contemporary interpretations and agendas". History and Anthropology. 13: 31–51. doi:10.1080/02757200290002879. S2CID 154790343 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "Malta's NeolithicTemples". www.carnaval.com. Retrieved 28 March 2021.