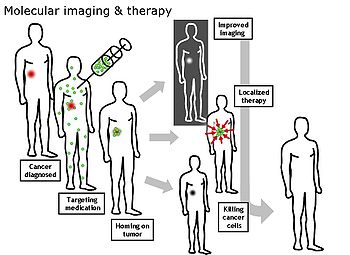

Molecular imaging is a field of medical imaging that focuses on imaging molecules of medical interest within living patients. This is in contrast to conventional methods for obtaining molecular information from preserved tissue samples, such as histology. Molecules of interest may be either ones produced naturally by the body, or synthetic molecules produced in a laboratory and injected into a patient by a doctor. The most common example of molecular imaging used clinically today is to inject a contrast agent (e.g., a microbubble, metal ion, or radioactive isotope) into a patient's bloodstream and to use an imaging modality (e.g., ultrasound, MRI, CT, PET) to track its movement in the body. Molecular imaging originated from the field of radiology from a need to better understand fundamental molecular processes inside organisms in a noninvasive manner.

The ultimate goal of molecular imaging is to be able to noninvasively monitor all of the biochemical processes occurring inside an organism in real time. Current research in molecular imaging involves cellular/molecular biology, chemistry, and medical physics, and is focused on: 1) developing imaging methods to detect previously undetectable types of molecules, 2) expanding the number and types of contrast agents available, and 3) developing functional contrast agents that provide information about the various activities that cells and tissues perform in both health and disease.

Overview

editMolecular imaging emerged in the mid twentieth century as a discipline at the intersection of molecular biology and in vivo imaging. It enables the visualisation of the cellular function and the follow-up of the molecular process in living organisms without perturbing them. The multiple and numerous potentialities of this field are applicable to the diagnosis of diseases such as cancer, and neurological and cardiovascular diseases. This technique also contributes to improving the treatment of these disorders by optimizing the pre-clinical and clinical tests of new medication. They are also expected to have a major economic impact due to earlier and more precise diagnosis. Molecular and Functional Imaging has taken on a new direction since the description of the human genome. New paths in fundamental research, as well as in applied and industrial research, render the task of scientists more complex and increase the demands on them. Therefore, a tailor-made teaching program is in order.

Molecular imaging differs from traditional imaging in that probes known as biomarkers are used to help image particular targets or pathways. Biomarkers interact chemically with their surroundings and in turn alter the image according to molecular changes occurring within the area of interest. This process is markedly different from previous methods of imaging which primarily imaged differences in qualities such as density or water content. This ability to image fine molecular changes opens up an incredible number of exciting possibilities for medical application, including early detection and treatment of disease and basic pharmaceutical development. Furthermore, molecular imaging allows for quantitative tests, imparting a greater degree of objectivity to the study of these areas. One emerging technology is MALDI molecular imaging based on mass spectrometry.[citation needed]

Many areas of research are being conducted in the field of molecular imaging. Much research is currently centered on detecting what is known as a predisease state or molecular states that occur before typical symptoms of a disease are detected. Other important veins of research are the imaging of gene expression and the development of novel biomarkers. Organizations such as the SNMMI Center for Molecular Imaging Innovation and Translation (CMIIT) have formed to support research in this field. In Europe, other "networks of excellence" such as DiMI (Diagnostics in Molecular Imaging) or EMIL (European Molecular Imaging Laboratories) work on this new science, integrating activities and research in the field. In this way, a European Master Programme "EMMI" is being set up to train a new generation of professionals in molecular imaging.

Recently the term molecular imaging has been applied to a variety of microscopy and nanoscopy techniques including live-cell microscopy, Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF)-microscopy, STimulated Emission Depletion (STED)-nanoscopy and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) as here images of molecules are the readout.

Imaging modalities

editThere are many different modalities that can be used for noninvasive molecular imaging. Each have their different strengths and weaknesses and some are more adept at imaging multiple targets than others.

Magnetic resonance imaging

editMRI has the advantages of having very high spatial resolution and is very adept at morphological imaging and functional imaging. MRI does have several disadvantages though. First, MRI has a sensitivity of around 10−3 mol/L to 10−5 mol/L which, compared to other types of imaging, can be very limiting. This problem stems from the fact that the difference between atoms in the high energy state and the low energy state is very small. For example, at 1.5 Tesla, a typical field strength for clinical MRI, the difference between high and low energy states is approximately 9 molecules per 2 million.[citation needed] Improvements to increase MR sensitivity include increasing magnetic field strength, and hyperpolarization via optical pumping, dynamic nuclear polarization or parahydrogen induced polarization. There are also a variety of signal amplification schemes based on chemical exchange that increase sensitivity.[1]

To achieve molecular imaging of disease biomarkers using MRI, targeted MRI contrast agents with high specificity and high relaxivity (sensitivity) are required. To date, many studies have been devoted to developing targeted-MRI contrast agents to achieve molecular imaging by MRI. Commonly, peptides, antibodies, or small ligands, and small protein domains, such as HER-2 affibodies, have been applied to achieve targeting. To enhance the sensitivity of the contrast agents, these targeting moieties are usually linked to high payload MRI contrast agents or MRI contrast agents with high relaxivities.[2] In particular, the recent development of micron-sized particles of iron oxide (MPIO) allowed to reach unprecedented levels of sensitivity to detect proteins expressed by arteries and veins.[3]

Optical imaging

editThere are a number of approaches used for optical imaging. The various methods depend upon fluorescence, bioluminescence, absorption or reflectance as the source of contrast.[4]

Optical imaging's most valuable attribute is that it and ultrasound do not have strong safety concerns like the other medical imaging modalities.[citation needed]

The downside of optical imaging is the lack of penetration depth, especially when working at visible wavelengths. Depth of penetration is related to the absorption and scattering of light, which is primarily a function of the wavelength of the excitation source. Light is absorbed by endogenous chromophores found in living tissue (e.g. hemoglobin, melanin, and lipids). In general, light absorption and scattering decreases with increasing wavelength. Below ~700 nm (e.g. visible wavelengths), these effects result in shallow penetration depths of only a few millimeters. Thus, in the visible region of the spectrum, only superficial assessment of tissue features is possible. Above 900 nm, water absorption can interfere with signal-to-background ratio. Because the absorption coefficient of tissue is considerably lower in the near infrared (NIR) region (700-900 nm), light can penetrate more deeply, to depths of several centimeters.[5]

Near Infrared imaging

editFluorescent probes and labels are an important tool for optical imaging. Some researchers have applied NIR imaging in rat model of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), using a peptide probe that can binds to apoptotic and necrotic cells.[6] A number of near-infrared (NIR) fluorophores have been employed for in vivo imaging, including Kodak X-SIGHT Dyes and Conjugates, Pz 247, DyLight 750 and 800 Fluors, Cy 5.5 and 7 Fluors, Alexa Fluor 680 and 750 Dyes, IRDye 680 and 800CW Fluors. Quantum dots, with their photostability and bright emissions, have generated a great deal of interest; however, their size precludes efficient clearance from the circulatory and renal systems while exhibiting long-term toxicity.[citation needed].

Several studies have demonstrated the use of infrared dye-labeled probes in optical imaging.

- In a comparison of gamma scintigraphy and NIR imaging, a cyclopentapeptide dual-labeled with 111

In and an NIR fluorophore was used to image αvβ3-integrin positive melanoma xenografts.[7] - Near-infrared labeled RGD targeting αvβ3-integrin has been used in numerous studies to target a variety of cancers.[8]

- An NIR fluorophore has been conjugated to epidermal growth factor (EGF) for imaging of tumor progression.[9]

- An NIR fluorophore was compared to Cy5.5, suggesting that longer-wavelength dyes may produce more effective targeting agents for optical imaging.[10]

- Pamidronate has been labeled with an NIR fluorophore and used as a bone imaging agent to detect osteoblastic activity in a living animal.[11]

- An NIR fluorophore-labeled GPI, a potent inhibitor of PSMA (prostate specific membrane antigen).[12]

- Use of human serum albumin labeled with an NIR fluorophore as a tracking agent for mapping of sentinel lymph nodes.[13]

- 2-Deoxy-D-glucose labeled with an NIR fluorophore.[14]

It is important to note that addition of an NIR probe to any vector can alter the vector's biocompatibility and biodistribution. Therefore, it can not be unequivocally assumed that the conjugated vector will behave similarly to the native form.

Single photon emission computed tomography

editThe development of computed tomography in the 1970s allowed mapping of the distribution of the radioisotopes in the organ or tissue, and led to the technique now called single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

The imaging agent used in SPECT emits gamma rays, as opposed to the positron emitters (such as 18

F) used in PET. There are a range of radiotracers (such as 99m

Tc, 111

In, 123

I, 201

Tl) that can be used, depending on the specific application.

Xenon (133

Xe) gas is one such radiotracer. It has been shown to be valuable for diagnostic inhalation studies for the evaluation of pulmonary function; for imaging the lungs; and may also be used to assess rCBF. Detection of this gas occurs via a gamma camera—which is a scintillation detector consisting of a collimator, a NaI crystal, and a set of photomultiplier tubes.

By rotating the gamma camera around the patient, a three-dimensional image of the distribution of the radiotracer can be obtained by employing filtered back projection or other tomographic techniques. The radioisotopes used in SPECT have relatively long half lives (a few hours to a few days) making them easy to produce and relatively cheap. This represents the major advantage of SPECT as a molecular imaging technique, since it is significantly cheaper than either PET or fMRI. However it lacks good spatial (i.e., where exactly the particle is) or temporal (i.e., did the contrast agent signal happen at this millisecond, or that millisecond) resolution. Additionally, due to the radioactivity of the contrast agent, there are safety aspects concerning the administration of radioisotopes to the subject, especially for serial studies.

Positron emission tomography

editPositron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear medicine imaging technique which produces a three-dimensional image or picture of functional processes in the body. The theory behind PET is simple enough. First a molecule is tagged with a positron emitting isotope. These positrons annihilate with nearby electrons, emitting two 511 keV photons, directed 180 degrees apart in opposite directions. These photons are then detected by the scanner, which can estimate the density of positron annihilations in a specific area. When enough interactions and annihilations have occurred, the density of the original molecule may be measured in that area. Typical isotopes include 11

C, 13

N, 15

O, 18

F, 64

Cu, 62

Cu, 124

I, 76

Br, 82

Rb, 89

Zr and 68

Ga, with 18

F being the most clinically utilized. One of the major disadvantages of PET is that most of the probes must be made with a cyclotron. Most of these probes also have a half life measured in hours, forcing the cyclotron to be on site. These factors can make PET prohibitively expensive. PET imaging does have many advantages though. First and foremost is its sensitivity: a typical PET scanner can detect between 10−11 mol/L to 10−12 mol/L concentrations.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Gallagher, F.A. (2010). "An introduction to functional and molecular imaging with MRI". Clinical Radiology. 65 (7): 557–566. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2010.04.006. ISSN 0009-9260. PMID 20541655.

- ^ Shenghui, Xue; Jingjuan Qiao; Fan Pu; Mathew Cameron; Jenny J. Yang (17 Jan 2013). "Design of a novel class of protein-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents for the molecular imaging of cancer biomarkers". Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 5 (2): 163–79. doi:10.1002/wnan.1205. PMC 4011496. PMID 23335551.

- ^ Gauberti M, Montagne A, Quenault A, Vivien D (2014). "Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of brain-immune interactions". Front Cell Neurosci. 8: 389. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00389. PMC 4245913. PMID 25505871.

- ^ Weissleder R, Mahmood U (May 2001). "Molecular imaging". Radiology. 219 (2): 316–33. doi:10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma19316. PMID 11323453.

- ^ Kovar JL, Simpson MA, Schutz-Geschwender A, Olive DM (August 2007). "A systematic approach to the development of fluorescent contrast agents for optical imaging of mouse cancer models". Anal. Biochem. 367 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2007.04.011. PMID 17521598. as PDF Archived February 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Acharya, B; Wang, K; Kim, IS; Kang, W; Moon, C; Lee, BH (2013). "In vivo imaging of myocardial cell death using a peptide probe and assessment of long-term heart function". Journal of Controlled Release. 172 (1): 367–73. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.08.294. PMID 24021357.

- ^ Houston JP, Ke S, Wang W, Li C, Sevick-Muraca EM (2005). "Quality analysis of in vivo near-infrared fluorescence and conventional gamma images acquired using a dual-labeled tumor-targeting probe". J Biomed Opt. 10 (5): 054010. Bibcode:2005JBO....10e4010H. doi:10.1117/1.2114748. PMID 16292970.

- ^ Chen K, Xie J, Chen X (2009). "RGD-human serum albumin conjugates as efficient tumor targeting probes". Mol Imaging. 8 (2): 65–73. doi:10.2310/7290.2009.00011. PMC 6366843. PMID 19397852. Archived from the original on 2014-03-26.

- ^ Kovar JL, Johnson MA, Volcheck WM, Chen J, Simpson MA (October 2006). "Hyaluronidase expression induces prostate tumor metastasis in an orthotopic mouse model". Am. J. Pathol. 169 (4): 1415–26. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.060324. PMC 1698854. PMID 17003496.

- ^ Adams KE, Ke S, Kwon S, et al. (2007). "Comparison of visible and near-infrared wavelength-excitable fluorescent dyes for molecular imaging of cancer". J Biomed Opt. 12 (2): 024017. Bibcode:2007JBO....12b4017A. doi:10.1117/1.2717137. PMID 17477732. S2CID 39806507.

- ^ Zaheer A, Lenkinski RE, Mahmood A, Jones AG, Cantley LC, Frangioni JV (December 2001). "In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of osteoblastic activity". Nat. Biotechnol. 19 (12): 1148–54. doi:10.1038/nbt1201-1148. PMID 11731784. S2CID 485155.

- ^ Humblet V, Lapidus R, Williams LR, et al. (2005). "High-affinity near-infrared fluorescent small-molecule contrast agents for in vivo imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen". Mol Imaging. 4 (4): 448–62. doi:10.2310/7290.2005.05163. PMID 16285907.

- ^ Ohnishi S, Lomnes SJ, Laurence RG, Gogbashian A, Mariani G, Frangioni JV (2005). "Organic alternatives to quantum dots for intraoperative near-infrared fluorescent sentinel lymph node mapping". Mol Imaging. 4 (3): 172–81. doi:10.1162/15353500200505127. PMID 16194449.

- ^ Kovar JL, Volcheck W, Sevick-Muraca E, Simpson MA, Olive DM (January 2009). "Characterization and performance of a near-infrared 2-deoxyglucose optical imaging agent for mouse cancer models". Anal. Biochem. 384 (2): 254–62. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2008.09.050. PMC 2720560. PMID 18938129. as PDF Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine