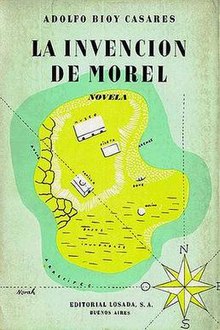

La invención de Morel (Latin American Spanish: [lajmbenˈsjon de moˈɾel]; 1940) — translated as The Invention of Morel or Morel's Invention — is a novel by Argentine writer Adolfo Bioy Casares. It was Bioy Casares' breakthrough effort, for which he won the 1941 First Municipal Prize for Literature of the City of Buenos Aires.[1] He considered it the true beginning of his literary career, despite being his seventh book. The first edition cover artist was Norah Borges, sister of Bioy Casares' lifelong friend, Jorge Luis Borges.

First edition dust jacket cover | |

| Author | Adolfo Bioy Casares |

|---|---|

| Original title | La invención de Morel |

| Translator | Ruth L. C. Simms |

| Cover artist | Norah Borges |

| Language | Spanish |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Publisher | Editorial Losada |

Publication date | 1940 |

| Publication place | Argentina |

Plot introduction

editA fugitive hides on a deserted island somewhere in Polynesia. Tourists arrive, and his fear of being discovered becomes a mixed emotion when he falls in love with one of them. He wants to tell her his feelings, but an anomalous phenomenon keeps them apart.

Plot summary

editThe fugitive starts a diary after tourists arrive on the desert island where he is hiding.[2] Although he considers their presence a miracle, he is afraid they will turn him in to the authorities. He retreats to the swamps while they take over the museum on top of the hill where he used to live. The diary described the fugitive as a writer from Venezuela sentenced to life in prison. He believes he is on the (fictional) island of Villings, a part of the Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu), but is not sure. All he knows is that the island is the focus of a strange disease whose symptoms are similar to radiation poisoning.

Among the tourists is a woman who watches the sunset every day from the cliff on the west side of the island. He spies on her and while doing so falls in love. She and another man, a bearded tennis player called Morel who visits her frequently, speak French among themselves. Morel calls her Faustine. The fugitive decides to approach her, but she does not react to him. He assumes she is ignoring him; however, his encounters with the other tourists have the same result. Nobody on the island notices him. He points out that the conversations between Faustine and Morel repeat every week and fears he is going crazy.

As suddenly as they appeared, the tourists vanish. The fugitive returns to the museum to investigate and finds no evidence of people being there during his absence. He attributes the experience to a hallucination caused by food poisoning, but the tourists reappear that night. They have come out of nowhere and yet they talk as if they have been there for a while. He watches them closely while still avoiding direct contact and notices more strange things. In the aquarium he encounters identical copies of the dead fish he found on his day of arrival. During a day at the pool, he sees the tourists jump to shake off the cold when the heat is unbearable. The strangest thing he notices is the presence of two suns and two moons in the sky.

He comes up with all sorts of theories about what is happening on the island, but finds out the truth when Morel tells the tourists he has been recording their actions of the past week with a machine of his invention, which is capable of reproducing reality. He claims the recording will capture their souls, and through looping they will relive that week forever and he will spend eternity with the woman he loves. Although Morel does not mention her by name, the fugitive is sure he is talking about Faustine.

After hearing that the people recorded on previous experiments are dead, one of the tourists guesses correctly they will die, too. The meeting ends abruptly as Morel leaves in anger. The fugitive picks up Morel's cue cards and learns the machine keeps running because the wind and tide feed it with an endless supply of kinetic energy. He understands that the phenomena of the two suns and two moons are a consequence of what happens when the recording overlaps reality — one is the real sun and the other one represents the sun's position at recording time. The other strange things that happen on the island have a similar explanation.

He imagines all the possible uses for Morel's invention, including the creation of a second model to resurrect people. Despite this he feels repulsion for the "new kind of photographs" that inhabit the island, but as time goes by he accepts their existence as something better than his own. He learns how to operate the machine and inserts himself into the recording so it looks like he and Faustine are in love, even though she might have slept with Alec and Haynes. This bothers him, but he is confident it will not matter in the eternity they will spend together. At least he is sure she is not Morel's lover.

On the diary's final entry the fugitive describes how he is waiting for his soul to pass onto the recording while dying. He asks a favor of the man who will invent a machine capable of merging souls based on Morel's invention. He wants the inventor to search for them and let him enter Faustine's consciousness as an act of mercy.

Characters

edit- The Fugitive: He is the only real person on the island as everybody else is part of the recording. The state of paranoia he reflects on the diary opens the possibility that he is hallucinating. He seems to be educated, yet he does not recall well Tsutomu Sakuma's final message (see "Allusions/references to actual history" below). He also ignores that Villings could not be part of Tuvalu because the islands of this archipelago are atolls. They are flat, barely above sea level, with no hills or cliffs, unlike Villings. His final speech indicates that he is a Venezuelan who is fleeing the law for political reasons.

- Faustine: She looks like a Gypsy, speaks French like a South American and likes to talk about Canada. She is inspired by silent film star Louise Brooks.

- Morel: He is the scientific genius who willingly leads a group of snobs to their death. The fugitive dislikes him out of jealousy, but in the end justifies his actions. His name is a salute to the analogous character of The Island of Doctor Moreau.

- Dalmacio Ombrellieri: He is an Italian rug merchant living in Calcutta (now Kolkata.) He tells the fugitive about the island and helps him get there.

- Alec: He is a shy oriental wool dealer with green eyes. He could be the lover of either Faustine or Dora, or just their confidant. As with the rest of the people from the group, he sees Morel as a messianic figure.

"Péle", Pelegrina Pastorino, Lady's Fashion Catalogue, Spring Season Harrods editorial, March 1925 - Dora: She is a blonde woman with a big head, she looks German but speaks Italian and walks like she is at the Folies Bergère, she is a close friend of Alec and Faustine. The fugitive hopes that she, and not Faustine, is Alec's lover. He later considers her as Morel's love interest when he suspects Morel might not be in love with Faustine after all. Dora's character is inspired by Bioy's friend, the model "Péle".

- Irene: She is a tall woman with long arms and an expression of disgust that does not believe their exposure to the machine will kill them. The fugitive thinks that if Morel is neither in love with Faustine nor Dora, then he is in love with her.

- Old Lady: She is probably related to Dora, because they are always together. She is drunk the night of the speech, but the fugitive still considers she could be Morel's love interest in case he is not in love with any of the other women.

- Haynes: He is asleep at the time Morel is about to give his speech. Dora says he is in Faustine's bedroom and that no one will get him out of there because he is heavy. It is unknown why he is there, but the fugitive is not jealous of him. Morel gives the speech anyway.

- Stoever: He is the one who guesses they are all going to die. The other members of the group prevent him from following Morel when he leaves the aquarium. He calms down and the group's fanaticism towards Morel prevails over his own survival instinct.

Allusions/references

edit- Throughout the novel the fugitive cites the views of Thomas Robert Malthus on population control as the only way to prevent chaos if humanity uses Morel's invention to achieve immortality. He also wants to write a book entitled Praise to Malthus.

- Before he finds out the truth about the island, the fugitive cites Cicero's book De Natura Deorum as an explanation of the appearance of two suns in the sky.

- The tourists like to dance to the song "Tea for Two" from the Broadway musical No, No, Nanette. This foreshadows the fugitive's love for Faustine.

- While trapped in the machine's room the fugitive promises himself he will not die like the Japanese folk hero Tsutomu Sakuma, one of the victims of Japan's first submarine accident.

- About 19 minutes into Eliseo (Ernesto) Subiela's film Man Facing Southeast, the psychiatrist Dr. Denis reads aloud from La invención de Morel as he struggles to identify his patient.

- In Georges Perec's 1969 experimental novel A Void, insomniac Anton Vowl hallucinates an abridged and misremembered version of the plot of La invención de Morel. In the text the book is given the name La Croix du Sud (The Southern Cross) by Isidro Parodi/Honorio Bustos Domaicq - respectively the protagonist and pseudonymous author of Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi, a book written by Casares in collaboration with Borges.

Literary significance and criticism

editJorge Luis Borges wrote in the introduction: "To classify it [the novel's plot] as perfect is neither an imprecision nor a hyperbole." Mexican Nobel Prize winner in Literature Octavio Paz echoed Borges when he said: "The Invention of Morel may be described, without exaggeration, as a perfect novel." Other Latin American writers such as Julio Cortázar, Juan Carlos Onetti, Alejo Carpentier and Gabriel García Márquez[1] have also expressed their admiration for the novel.

Awards and nominations

edit- First Municipal Prize for Literature of the City of Buenos Aires, 1941

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

edit- In 1967 it was made into a French movie called L'invention de Morel.

- In 1974 it was made into an Italian movie called L'invenzione di Morel.

- In 1995 it was made into a puppet show featuring a real life actor as the fugitive.[4]

- The TV show Lost was partially based on "The Invention of Morel"; in Season 4, Episode 4, the character James 'Sawyer' Ford is seen reading the book.[5]

- In 2017 it had its world premiere as an opera (by Stewart Copeland) in a co-commission by Long Beach Opera and Chicago Opera Theater [6]

The 1961 movie Last Year at Marienbad has been attributed by many film critics[7][8] to be directly inspired by The Invention of Morel; however, screenwriter Alain Robbe-Grillet denied any influence of the book on the film (although Robbe-Grillet had read it and was familiar with Bioy Casares' work).[9]

References

edit- ^ a b "Southern Cone Literature: Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999)". Library.nd.edu. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ "Rosario, Felix M. "Writing and Paranoid Scrutiny in Adolfo Bioy Casares' The Invention of Morel"". Mester at UCLA. 2019. doi:10.5070/M3481041865. S2CID 214516989. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Playing in Peoria: The Invention of Morel". Nyrb.typepad.com. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ "Morel's Invention". Archived from the original on November 5, 2002. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "La invención de Morel". Animal Político. 12 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ "OPERA NEWS - The Invention of Morel". Operanews.com. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Beltzer, Thomas. "Last Year at Marienbad: An Intertextual Meditation – Senses of Cinema".

- ^ "The Invention of Morel". New York Review Books.

- ^ "The Invention of Marienbad: Resnais, Robbe-Grillet, Morel, and Adolfo Bioy Casares on the Left Bank". Bright Lights Film Journal. 14 August 2021.

External links

edit- Rosario, Felix M. Writing and Paranoid Scrutiny in Adolfo Bioy Casares' The Invention of Morel. Mester at UCLA, vol. 48, no. 1, 2019, pp. 23–42.

- The opening to The Invention of Morel in English

- Analysis of Ruth Simms' translation of The Invention of Morel

- Review by Seamus Sweeney on nthposition.com

- Review on waggish.org

- Essay on the novel

- English page about the 1996 installation