Moroccan–American Treaty of Friendship

The Moroccan–American Treaty of Peace and Friendship, also known as the Treaty of Marrakesh,[1] was a bilateral agreement signed in 1786 that established diplomatic and commercial relations between the United States and Morocco.[2] It was the first treaty between the U.S. and an African, Muslim nation, and initiated what as of 2024[update] remains the longest unbroken diplomatic relationship in U.S. history.[3]

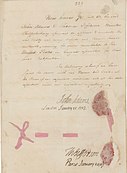

Moroccan–American Treaty of Friendship (Treaty of Marrakesh), 1786–1787 | |

| Signed | 28 June 1786, 15 July 1786 |

|---|---|

| Location | Marrakesh, Morocco |

| Original signatories | |

Nearly a decade before the treaty, on 20 December 1777, Moroccan Sultan Mohammed III, decreed that American ships could freely enter his kingdom's ports and enjoy safe passage through its waters; and became one of the first heads of state to publicly recognize U.S. independence during the American Revolutionary War.[4][5]

Following several overtures by the Sultan, and with the urging of John Adams, John Jay, and Benjamin Franklin, in 1785 the U.S. Congress authorized negotiations for a treaty with Morocco. American diplomat Thomas Barclay was chosen to represent the U.S., and with the aid and backing of Spain, met his Moroccan counterpart, Tahir Fannish, in Marrakesh in June 1786. The treaty was finalized within days of Barclay's arrival, sealed by Mohammed III, and signed by Thomas Jefferson and John Adams at their respective diplomatic posts in Paris and London; Congress ratified the treaty on 18 July 1787, which was to last fifty years.[6][7]

Background

editMuhammad III, or Sidi Muhammad bin Abdallah, came to power in 1757 and ruled until his death in 1790. Prior to his reign, Morocco had experienced 30 years of internecine battles, instability and turmoil. Sidi Muhammad transformed politics, the economy and society by prioritizing development of international trade and restoring power to the sultanate, which improved Morocco's standing internationally.[8] Central to his pursuit of international trade was the negotiation of agreements with foreign commercial powers. He began seeking one with the United States before the war with Great Britain had ended in 1783, and he welcomed Thomas Barclay's arrival to negotiate in 1786. The treaty signed by Barclay and the sultan and then by Jefferson and Adams was ratified by the Confederation Congress in 1787.[9] It was reaffirmed by the sultan in 1803, when the USS Constitution, Nautilus, New York, and Adams engaged in gunboat diplomacy as part of the First Barbary War. At the time, independent corsairs and pirates were using Morocco's ports as safe harbors between raids on American and European shipping. As of 2020[update], the treaty has withstood transatlantic stresses and strains for more than 235 years, which makes it the longest unbroken treaty relationship in United States history.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ History of the U.S. and Morocco - U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Morocco (usembassy.gov) " Also called the Treaty of Marrakech ..."

- ^ "History of the U.S. and Morocco". U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Morocco. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Ogot, General History of Africa, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla H.; Tull, James N. (June 1999). "Moroccan Sultan Sidi Muhammad Ibn Abdallah's Diplomatic Initiatives toward the United States, 1777–1786". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 143 (2): 233–265. JSTOR 3181936.

- ^ "History of the U.S. and Morocco". U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Morocco. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla H. and Richard S. Roberts, Thomas Barclay (1728–1793): Consul in France, Diplomat in Barbary. Lehigh University Press. 2008, pp. 158–223. ISBN 978-0-934223-98-0.

- ^ "US-Morocco: Longstanding Ties (Remarks by President Bush and King Hassan II); U.S. Department of State Dispatch". January 24, 2007.

- ^ B.A. Ogot, General History of Africa, Vol. V: Africa from the 16th to the 18th Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. pp. 231–232.

- ^ Roberts, Thomas Barclay (1728–1793)..., pp. 195–223

External links

edit- English text of the treaty from Yale's Lillian Goldman Law Library

- The Moroccan-American Treaty of Peace and Friendship, [28 June 1786]", Founders Online, National Archives

- "Long-time friends: a history of early U.S.-Moroccan relations 1777-1787" by Sherrill B. Wells, Embassy of the United States, Rabat, Morocco

- "Historical Background on United States - Morocco Relations", Embassy of the United States, Rabat, Morocco

- "Morocco-US relations", Embassy of the Kingdom of Morocco

- "Moroccan–U.S. Relations, 1750–1912", Moroccan American Trade and Investment Council

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State.