You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Polish. (October 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

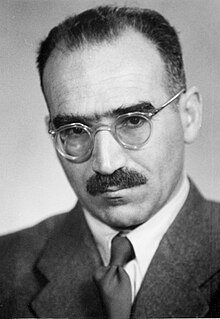

Aleksander Ford (born Mosze Lifszyc; 24 November 1908 in Kiev, Russian Empire – 4 April 1980 in Naples, Florida, U.S.) was a Polish film director and head of the Polish People's Army Film Crew in the Soviet Union during World War II. Following the war, he was appointed director of the Film Polski company.[1]

Aleksander Ford | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mosze Lifszyc November 24, 1908 |

| Died | April 4, 1980 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Occupation | Film director |

| Known for | Head of government-controlled Film Polski |

In 1948 he was appointed a professor of the National Film School in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa). Roman Polanski and Polish film director Andrzej Wajda were among his students. Amid an anti-Semitic purge in the communist party in Poland, Ford was stopped from preparing a film on the life of a Jewish educator.[2] Shortly afterwards he emigrated to Israel in 1968 and from there to the United States, going through Germany and Denmark. He took his own life in 1980 in Naples, Florida.[3]

Professional career

editFord made his first feature film, Mascot in 1930, after a year of making short silent films. He did not use sound until The Legion of the Streets (1932).[3]

In 1932 he directed one of the first movies made about the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine, "Sabra".[4]

When World War II began, Ford escaped to the Soviet Union and worked closely with Jerzy Bossak to establish a film unit for the Soviet-sponsored People's Army of Poland in the USSR. The unit was called Czołówka Filmowa Ludowego Wojska Polskiego (or simply Czołówka; spearhead).[3]

After the war, Ford was appointed head of the government-controlled Film Polski and held enormous sway over the country's entire film industry. In the process of accumulating power, he denounced a fellow film director Jerzy Gabryelski to the Soviet NKVD secret police, contentiously accusing him of "reactionary" and "antisemitic" views, which resulted in Gabryelski's arrest and torture.[5] Ford and a group of colleagues from the Polish Communist Party rebuilt most of the country's film production infrastructure. Roman Polanski wrote in his biography about them: "They included some extremely competent people, notably Aleksander Ford, a veteran party member, who was then an orthodox Stalinist. […] The real power broker during the immediate postwar period was Ford himself, who established a small film empire of his own." For the next twenty years, Ford served as a professor at the state-run National Film School in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa). He is perhaps best remembered for directing the first postwar documentary Majdanek - cmentarzysko Europy (Majdanek – the Cemetery of Europe) and the feature film Knights of the Teutonic Order (1960), based on a novel of the same name by Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz.[3]

Ford, a self-identified Communist, used his films to "express social messages on the screen," as in his documentaries: the award-winning Legion ulicy, (The Street Legion, 1932), Children Must Laugh (1936) and the postwar Eighth Day of the Week (1958) rejected by the communist party censors during the Polish October. Ford continued making films in Poland until the 1968 Polish political crisis. Accused of antisocialist activity and expelled from the Communist Party, Ford emigrated to Israel where he lived for the next two years. He later moved to Denmark and eventually settled in the United States. Ford made two more feature films, both of which were commercial and critical failures. In 1973, he made a film adaptation of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's novel The First Circle, a Danish-Swedish production that recounted the horrors of the Soviet gulag. In 1974 he made The Martyr, an English language, Israeli-German co-production based on the heroic story of Dr. Janusz Korczak. Blacklisted by the Polish communist government as a political defector, Ford became a non-person in contemporary discussions and analysis of Polish filmmaking. He committed suicide in a Florida hotel on 4 April 1980.[6]

Selected filmography

edit- The Martyr (1974)

- The First Circle (1973)

- The Doctor Speaks Out (1966)

- The First Day of Freedom (Pierwszy dzień wolności, 1964)

- Knights of the Teutonic Order (Krzyżacy, 1960)

- The Eighth Day of the Week (Ósmy dzień tygodnia, 1959)

- Five Boys from Barska Street (Piątka z ulicy Barskiej, 1954)

- Youth of Chopin (Młodość Chopina, 1952)

- Border Street (Ulica Graniczna, 1949)

- Majdanek: Cemetery of Europe (Majdanek - cmentarzysko Europy, 1945)

- Children Must Laugh (Droga młodych, original yiddish title: Mir kumen on, 1936)

- Granny Had No Worries (Nie miała baba kłopotu, 1935, co-directed with Michał Waszyński)

- Legion of the Streets (Legion Ulicy, 1932)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Richard Taylor, Nancy Wood, Julian Graffy, Dina Iordanova (2019). The BFI Companion to Eastern European and Russian Cinema. Bloomsbury. p. 1947. ISBN 978-1838718497.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Polish Film Producer Leaves Country when Film About Jew is Stopped Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 23 July 1969

- ^ a b c d Dr. Edyta Gawron, Department of Jewish Studies, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, "Contemporary history of Jews in Poland (1945-2005) – as Depicted in the Film." PDF file (direct download): 194.7 KB. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ Bar-Adon, Doron; et al. (2008). "A Hundred (and one) Years to the Birth of Pessah Bar-Adon" (in Hebrew).

- ^ Marek Chodakiewicz: After the Holocaust. Polish - Jewish relations 1944-1947.

- ^ Anna Misiak, "Politically Involved Filmmaker: Aleksander Ford and Film Censorship in Poland after 1945", Kinema, 2003

External links

edit- Aleksander Ford at IMDb

- Knights of the Teutonic Order - Aleksander Ford at Culture.pl