This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

A cortical homunculus (from Latin homunculus 'little man, miniature human'[1][2]) is a distorted representation of the human body, based on a neurological "map" of the areas and portions of the human brain dedicated to processing motor functions, and/ or sensory functions, for different parts of the body. Nerve fibres—conducting somatosensory information from all over the body—terminate in various areas of the parietal lobe in the cerebral cortex, forming a representational map of the body.

Findings from the 2010s and early 2020s began to call for a revision of the traditional "homunculus" model and a new interpretation of the internal body map (likely less simplistic and graphic), and research is ongoing in this field.[3]

Types

editMotor homunculus

editA motor homunculus represents a map of brain areas dedicated to motor processing for different anatomical divisions of the body. The primary motor cortex is located in the precentral gyrus, and handles signals coming from the premotor area of the frontal lobes.[4]

Sensory homunculus

editA sensory homunculus represents a map of brain areas dedicated to sensory processing for different anatomical divisions of the body. The primary sensory cortex is located in the postcentral gyrus, and handles signals coming from the thalamus.[4]

The thalamus itself receives corresponding signals from the brain stem and spinal cord.

Arrangement

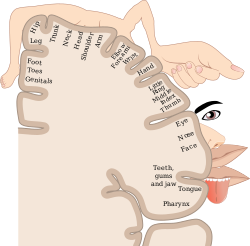

editAlong the length of the primary motor and sensory cortices, the areas specializing in different parts of the body are arranged in an orderly manner, although ordered differently than one might expect. The toes are represented at the top of the cerebral hemisphere (or more accurately, "the upper end," since the cortex curls inwards and down at the top), and then as one moves down the hemisphere, progressively higher parts of the body are represented, assuming a body that is faceless and has arms raised. Going further down the cortex, the different areas of the face are represented, in approximately top-to-bottom order, rather than bottom-to-top as before. The homunculus is split in half, with motor and sensory representations for the left side of the body on the right side of the brain, and vice versa.[5]

The amount of cortex devoted to any given body region is not proportional to that body region's surface area or volume, but rather to how richly innervated that region is. Areas of the body with more complex and/or more numerous sensory or motor connections are represented as larger in the homunculus, while those with less complex and/or less numerous connections are represented as smaller. The resulting image is that of a distorted human body, with disproportionately huge hands, lips, and face.

In the sensory homunculus, below the areas handling sensation for the teeth, gums, jaw, tongue, and pharynx lies an area for intra-abdominal sensation. At the very top end of the primary sensory cortex, beyond the area for the toes, it has traditionally been believed that the sensory neural networks for the genitals occur. However, more recent research has suggested that there may be two different cortical areas for the genitals, possibly differentiated by one dealing with erogenous stimulation and the other dealing with non-erogenous stimulation.[6][7][8]

Discovery

editWilder Penfield and his co-investigators Edwin Boldrey and Theodore Rasmussen are considered to be the originators of the sensory and motor homunculi. They were not the first scientists to attempt to objectify human brain function by means of a homunculus.[8] However, they were the first to differentiate between sensory and motor function and to map the two across the brain separately, resulting in two different homunculi. In addition, their drawings and later drawings derived from theirs became perhaps the most famous conceptual maps in modern neuroscience because they compellingly illustrated the data at a single glance.[8]

Penfield first conceived of his homunculi as a thought experiment, and went so far as to envision an imaginary world in which the homunculi lived, which he referred to as "if". He and his colleagues went on to experiment with electrical stimulation of different brain areas of patients undergoing open brain surgery to control epilepsy, and were thus able to produce the topographical brain maps and their corresponding homunculi.[8][9]

More recent studies have improved this understanding of somatotopic arrangement using techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).[10]

Representation

editPenfield referred to his creations as "grotesque creatures" due to their strange-looking proportions. For example, the sensory nerves arriving from the hands terminate over large areas of the brain, resulting in the hands of the homunculus being correspondingly large. In contrast, the nerves emanating from the torso or arms cover a much smaller area, thus the torso and arms of the homunculus look comparatively small and weak.

Penfield's homunculi are usually shown as 2-D diagrams. This is an oversimplification, as it cannot fully show the data set Penfield collected from his brain surgery patients. Rather than the sharp delineation between different body areas shown in the drawings, there is actually significant overlap between neighboring regions. The simplification suggests that lesions of the motor cortex will give rise to specific deficits in specific muscles. However, this is a misconception, as lesions produce deficits in groups of synergistic muscles. This finding suggests that the motor cortex functions in terms of overall movements as coordinated groups of individual motions.

The sensorimotor homunculi can also be represented as 3-D figures (such as the sensory homunculus sculpted by Sharon Price-James shown from different angles below), which can make it easier for laymen to understand the ratios between the levels of motor or sensory innervation of different body regions. However, these 3-D models do not illustrate which areas of the brain are associated with which parts of the body.

In a 2021 article by Haven Wright and Preston Foerder published in the peer-reviewed journal Leonardo entitled "The Missing Female Homunculus",[11] the authors revisit the history of the homunculus, shed light on current research in neuroscience on the female brain, and reveal what they believe to be the first sculpture of the female homunculus, done by the artist and first author Haven Wright, based on the current research available.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Definition of HOMUNCULUS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Homunculus | Meaning & Definition in UK English | Lexico.com". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Scientific American Dosenbach, NUF; How our team overturned the 90-year-old metaphor of a 'little man' in the brain who controls movement, April 21, 2023

- ^ a b Marieb, E.; Hoehn, K. (2007). Human Anatomy and Physiology (7th ed.). Pearson Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0805359091.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2007). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 544–6. ISBN 978-0073228044.

- ^ Covington, Jr., William Oates (2015-05-27). "Homunculus (Topographic) Diagram". willcov.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-03. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ^ Michels, L.; Mehnert, U.; Boy, S.; Schurch, B.; Kollias, S. (2009-08-10). "The Neurocritic: A New Clitoral Homunculus?". NeuroImage. 49 (1): 177–184. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.024. PMID 19631756. S2CID 11467584. Archived from the original on 2017-07-07. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ^ a b c d Cazala, Fadwa; Vienney, Nicolas; Stoléru, Serge (2015-03-10). "The cortical sensory representation of genitalia in women and men: a systematic review". Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology. 5: 26428. doi:10.3402/snp.v5.26428. PMC 4357265. PMID 25766001.

- ^ Penfield, Wilder; Boldrey, Edwin (1937). "Somatic Motor And Sensory Representation In The Cerebral Cortex Of Man As Studied By Electrical Stimulation". Brain. 60 (4): 389–443. doi:10.1093/brain/60.4.389.

- ^ Grodd, W.; Hülsmann, E.; Lotze, M.; Wildgruber, D.; Erb, M. (2001). "Sensorimotor mapping of the human cerebellum: fMRI evidence of somatotopic organization". Hum Brain Mapp. 13 (2): 55–73. doi:10.1002/hbm.1025. PMC 6871814. PMID 11346886.

- ^ Wright, Haven; Foerder, Preston (2021). "The Missing Female Homunculus". Leonardo. 54 (6): 1–8. doi:10.1162/leon_a_02012. S2CID 227275778.

External links

edit- Mole-ratunculus — an analog of a sensory homunculus for a mole-rat, from the paper:

- Catania, Kenneth C.; Remple, Michael S. (2002). "Somatosensory cortex dominated by the representation of teeth in the naked mole-rat brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (8): 5692–5697. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.5692C. doi:10.1073/pnas.072097999. PMC 122833. PMID 11943853. S2CID 8869228.

Fig. 3: ...This "mole-ratunculus" provides a graphic illustration of the cortical magnification of the incisors and head