Penglai (Chinese: 蓬萊仙島; lit. 'Penglai Immortal[1] Island') is a legendary land of Chinese mythology. It is known in Japanese mythology as Hōrai.[2]

| Mount Penglai | |

|---|---|

"The Immortal Island of Penglai", by Chinese artist Yuan Jiang (1708), held by Palace Museum | |

| Genre | Chinese mythology |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Legendary island of immortals, Otherworld |

| Characters | The Eight Immortals |

| Mount Penglai | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

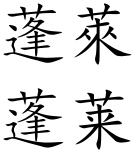

"Penglai" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蓬萊仙島 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蓬莱仙岛 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 蓬莱 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Location

editAccording to the Classic of Mountains and Seas, the mountain is located at the eastern end of Bohai Sea.[3] According to the pre-Qin mythology which retells the legend of Xu Fu presenting a memorial to the Qin Emperor in order to seek for the elixir of life, there are three godly mountains which are found in the Bohai sea where immortals reside; these mountains are Penglai, Fāngzhàng (方丈), and Yíngzhōu (瀛洲/瀛州).[4] Other islands where immortals reside are called Dàiyú (岱輿) and Yuánjiāo (員嬌).[5]

In the Illustrated Account of the Embassy to Goryeo in the Xuanhe Era (Chinese: 宣和奉使高麗圖經; Xuanhe fengshi Gaoli tujing), written in 1124 by Xu Jing (徐兢), Mount Penglai is located on an inhabited island which is found within the boundaries of Changguo prefecture and can be reached "after crossing thirty thousand leagues of the Weak Water".[6]

Various theories have been offered over the years as to the "real" location of these places, including Japan,[3] Nam-Hae (南海), Geo-Je (巨濟), Jejudo (濟州島) south of the Korean Peninsula, and Taiwan. Penglai, Shandong exists, but its claimed connection is as the site of departures for those leaving for the island rather than the island itself.[citation needed] In his work Taengniji (lit. "A Guide to Select Villages"), Yi Chung-hwan, a Joseon-period geographer, associated Mount Penglai with Korea's Mount Kumgang.[7]

In Chinese mythology

editIn a legend originating in the state of Qi during the pre-Qin period, immortals live in a palace called the Penglai Palace which is located on Mount Penglai.[3] In Chinese mythology the mountain is often said to be the base for the Eight Immortals (or at least where they travel to have a ceremonial meal), as well as the illusionist Anqi Sheng. Supposedly, everything on the mountain appears pure white, while its palaces are made from gold and silver, and jewels grow on trees. There is no agony and no winter; there are rice bowls and wine glasses that never become empty no matter how much people eat or drink from them; and there are enchanted fruits growing in Penglai that can heal any ailment, grant eternal youth, and even resurrect the dead.

Tradition holds that Qin Shi Huang, in search of immortality, sent several unsuccessful expeditions to find Penglai.[8]: 120 Legends tell that Xu Fu, one servant sent to find the island, found Japan instead, and named Mount Fuji as Penglai.

In Japanese mythology

editFrom the medieval periods onwards, Mount Penglai was believed by some Japanese people to be located in Japan where Xu Fu and Yang Guifei arrived and eventually decided to stay there for the rest of their lives.[3]

The presentation of Mt. Hōrai in Lafcadio Hearn's Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things differs from the earlier Chinese legend. This version rejects much of the fantastic and magical properties of Hōrai. In this version of the myth, Hōrai is not free from sorrow or death, and the winters are bitterly cold. Hearn's conception of Hōrai holds that there are no magical fruits that cure disease, grant eternal youth or raise the dead, and no rice bowls or wine glasses that never become empty; rather, Hearn's incarnation of the myth of Hōrai focuses more on the atmosphere of the place, which is said to be made up not of air but of "quintillions of quintillions" of souls. Breathing in these souls is said to grant one all of the perceptions and knowledge possessed by the ancient souls. The Japanese version also holds that the people of Hōrai are small fairies who have no knowledge of great evil, and whose hearts therefore never grow old.

In the Kwaidan there is some indication that the Japanese hold such a place to be merely a fantasy. It is pointed out that "Hōrai is also called Shinkiro, which signifies Mirage—the Vision of the Intangible".

See also

edit- Avalon

- Dilmun, paradise-island in the Epic of Gilgamesh

- Hōrai Valley

- Luggnagg, the island of the immortal struldbrugs in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels

- Penglai Pavilion

- Penglai, Shandong

- Shangri-La

- Tír na nÓg

References

edit- ^ The character 仙 literally refers to a Daoist holy person/immortal or a mythological being, but is often used to describe places which exhibit the qualities of these beings.

- ^ McCullough, Helen. Classical Japanese Prose, p. 570. Stanford Univ. Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8047-1960-8.

- ^ a b c d Ng, Wai-ming (2019). Imagining China in Tokugawa Japan : Legends, Classics, and Historical Terms. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-4384-7308-6. OCLC 1089524439.

- ^ Morio, Matsumoto (2006). A kaleidoscope of China. Yaping Guan, 官亚平. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she. p. 113. ISBN 7-5085-0997-8. OCLC 228035978.

- ^ Fabrizio Pregadio et al, The Encyclopedia of Taoism A-Z, vols 1&2, Routledge, 2008, p. 789.

- ^ Xu, Jing (2016). A Chinese traveler in medieval Korea : Xu Jing's illustrated account of the Xuanhe embassy to Koryo. Sem Vermeersch. Honolulu. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-8248-6683-9. OCLC 950971983.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kallander, George L. (2013). Salvation through dissent : Tonghak heterodoxy and early modern Korea. Honolulu. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-8248-3786-0. OCLC 859157560.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Reinders, Eric (2024). Reading Tolkien in Chinese: Religion, Fantasy, and Translation. Perspectives on Fantasy series. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781350374645.

- "Horai". Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (digital version @ sacred-texts.com). Retrieved February 22, 2006.