Mount Tamalpais (/tæməlˈpaɪɪs/; TAM-əl-PY-iss; Miwok: Támal Pájiṣ), known locally as Mount Tam, is a peak in Marin County, California, United States, often considered symbolic of Marin County. Much of Mount Tamalpais is protected within public lands such as Mount Tamalpais State Park, the Marin Municipal Water District watershed, and National Park Service land, such as Muir Woods.

| Mount Tamalpais | |

|---|---|

Mount Tamalpais, viewed from the southeast | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,579 ft (786 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 2,456 ft (749 m)[1] |

| Listing | California county high points 55th |

| Coordinates | 37°55′45″N 122°34′40″W / 37.929088°N 122.577829°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Native name |

|

| Geography | |

| Location | Marin County, California, U.S. |

| Parent range | California Coast Ranges |

| Topo map | USGS San Rafael |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Sedimentary |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1830s by Jacob P. Leese (first recorded ascent)[2] |

| Easiest route | Railroad Grade fire trail |

Toponym

editThe name Tamalpais was first recorded in 1845. It comes from the Coast Miwok name for this mountain, támal pájiṣ, meaning "west hill".[3]

Various different folk etymologies also exist, but they are unsubstantiated. One holds that it comes from the Spanish Tamal país, meaning "Tamal country," Tamal being the name that the Spanish missionaries gave to the Coast Miwok people. Another holds that the name is the Coast Miwok word for "sleeping maiden" and is taken from a "Legend of the Sleeping Maiden"[4][5][6] Supposedly, the legend is that the mountain's contour reflects the reclining profile of a young Miwok girl who was saved from a rival tribe by the shuddering of the mountain.[5] However, this legend actually has no basis in Coast Miwok myth and is instead a piece of Victorian-era apocrypha.[6][7][8] The "Sleeping Lady" story was the creation of playwright Dan Totheroh, who wrote the first play performed at Mt. Tamalpais' Mountain Theater about Tamelpa, the Mountain Queen. Another suggests a tie to the Eurasian origins of the Miwoks, where "pais" means place and "tamal" is a tribe in Siberia.[9]

Geography

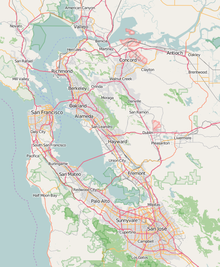

editMount Tamalpais is the highest peak in the Marin Hills, which are part of the Northern California Coast Ranges. The elevation at the West Peak, where a radar dome currently stands, is between 2,560 feet (780 m) and 2,578 feet (786 m)[10] It stood over 2,600 feet (792 m) before the summit was flattened for the radar dome construction.[citation needed] The East Peak is at 2,571 feet (784 m).[11] The mountain is clearly visible from parts of San Francisco and the East Bay.

The majority of the mountain is contained in protected public lands, including Mount Tamalpais State Park, Muir Woods National Monument, and the Mount Tamalpais Watershed. It adjoins the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (which in turn adjoins Point Reyes National Seashore) as well as several Marin County Open Space Preserves. This provides nearly 40 miles (64 km) of continuous publicly accessible open space. Some of the lower slopes of Mount Tamalpais fall within several cities and unincorporated communities of Marin County, including Mill Valley, Tamalpais-Homestead Valley, Stinson Beach, and Kentfield. These areas are generally developed, consisting of mostly low-density single-family homes.

Natural history

editGeology and soils

editLike the rest of the California Coast Ranges, Mount Tamalpais is the result of uplift, buckling, and folding of the North American Plate as it slides along the Pacific Plate near the San Andreas Fault zone.

In 2004, a team of Penn State geoscientists suggested that a blind thrust fault, like the one that caused the infamous Northridge earthquake, lies beneath Mount Tamalpais. This idea was partly based on the steepness of Mount Tamalpais and of nearby Bolinas Ridge, such steepness on the visible surface often being the result of blind thrust faults. Another reason for the suggestion was that the San Andreas Fault creeps more slowly south of Mount Tamalpais than it does in its sections north of Mount Tamalpais and in the Olema Valley, and that the existence of a blind thrust fault may explain the different creeping velocities. If a blind thrust fault does exist under Mount Tamalpais, and if it ruptures, it could be potentially devastating to the North Bay, San Francisco, and any other nearby locale resting on unstable earth and loose fill.[12]

Major Mount Tamalpais rockforms include serpentine, particularly evident in outcroppings near the summit and on the north side. A number of serpentine endemic plants grow in the serpentine soils in this part of the mountain.

Hydrology

editSince the steep slopes of Mount Tamalpais force out moisture from passing storms and/or fog, the mountain supports several year-round streams like Redwood Creek on the southern face of the mountain down into Muir Woods. The steep southeastern slopes of Mount Tamalpais drain to Arroyo Corte Madera del Presidio, which in turn discharges to Richardson Bay.

Climate

editWith its height, various faces, and proximity to the ocean and bay, the mountain contains many microclimates, ranging from cool and foggy in lower ocean-facing valleys with their redwood forests, to hot and dry on the manzanita slopes, cool and breezy at the summit, and shady on the heavily Douglas-fir-forested north slopes near Alpine Lake.

Annual precipitation[13] around Mount Tamalpais varies greatly from around 27.5–31.5 inches (700–800 mm) in the drier, eastern foothills to about 59 inches (1,500 mm) near the Bolinas Ridge, close to the Pacific Ocean. Both Mount Tamalpais and the Bolinas Ridge force moisture out of the air efficiently, since the air is cooled rapidly as it ascends the steep mountain faces and thus Mount Tamalpais's western part is heavily forested with tall redwoods and Douglas firs. The same fact holds for the steep, south-facing bowl canyon that Muir Woods is located in, with precipitation in Redwood Canyon at around 39.4–47.2 inches (1,000–1,200 mm).[14]

As in San Francisco, most of the annual precipitation falls during the winter months. During cold, wet winter storms, the mountain also regularly gets some snowfall, sometimes as much as 6 inches (15 cm) overnight, as observed in February 2001, March 2006, February 2011, February 2019, and February 2023.[15][16][17] The region sometimes gets hit with strong Pacific storms that may topple trees, and bring hurricane-force winds to exposed, barren areas like the Bolinas Ridge and the summit of Mount Tamalpais. In summer, the area gets almost no precipitation, except for fog drip[18] that occurs in Muir Woods, the Bolinas Ridge and the western end of Mount Tamalpais, where summer fog and oceanic breezes are more prevalent. In contrast, the eastern foothills, sheltered from the oceanic breezes and fog, are drier, since the foothills force little moisture out of the air. This leads to the fact that the eastern slopes contain only oak, pine, chaparral shrub, coastal sage scrub, grassland and sparse Douglas-fir forest. Coastal sage scrub also occurs on some of the exposed coastal slopes.

Temperatures on top of Mount Tamalpais are generally somewhat cooler than places next to the San Francisco Bay or the ocean due to elevation. In summer, however, the top of Mount Tamalpais may actually be warmer than the middle, foggy elevations due to a thermal inversion. The summer fog and breezes make locations on Mount Tamalpais, closer to the ocean, cooler than the blazing hot interior valleys.

Plant communities

editHardwood woodland types are generally subtypes of California oak woodland, including oak-bay-madrone forest, oak woodland, and oak savannah. Oak-bay-madrone forests are found in areas with moderate moisture and particularly favor north-facing slopes. They are dominated by one or more of three hardwood tree species – Coast Live Oak, California bay, and madrone. Coast live oak tends to be dominant in somewhat drier areas, while bay is more dominant in shadier, moister areas; madrone is abundant in certain soil types in both moist and dry spots. Oak woodlands are a more open-canopy forest dominated by coast live oak, while oak savannah has a completely open canopy and represents a mixture of coast live oak woodland and grassland.[19]

The great diversity of microclimates on Mount Tamalpais ensures a wide variety of plant communities as well. Plant communities on the mountain include various types of hardwood and coniferous forests, coastal scrub, chaparral, grassland, and wetland vegetation. Wholly or partially coniferous forest types are found in the moistest areas of Mount Tamalpais. Coast redwood forests are restricted to areas where the particular ecological needs of redwood are met: areas characterized by high overall moisture, low elevations below the fog line, and deep soils. Muir Woods is the most extensive and best-known redwood forest of the Mount Tamalpais area. Mixed evergreen forests of various combinations of tanoak, madrone, coast and canyon live oak, and Douglas-fir are found in moist areas on middle to high elevations on the mountain. Very moist areas of mixed evergreen forest may also include bay, redwood, and California torreya. Areas in which mixed evergreen forests are predominant include areas of Fairfax-Bolinas Road and Ridgecrest Boulevard and around Alpine Lake.[19]

Various kinds of scrub communities are also widespread. Low-elevation areas below the fog line with relatively low overall rainfall or thin soils are often the site of a northern coastal scrub community characterized by coastal sage-coyote brush association, with lesser amounts of poison-oak, bush monkeyflower, California blackberry, western bracken fern, and various species of grasses and forbs. Chaparral is predominant in areas characterized by thin, rocky soils and little moisture. Two main types of chaparral are found the mountain chamise chaparral and manzanita chaparral. Chamise is dominant in the hottest, most xeric areas of the mountain, particularly on south- and west-facing slopes, while manzanita is dominant in other xeric areas, particularly on east-facing slopes and forest borders. Areas of mixed chamise-manzanita chaparral occur in relatively more mesic areas; Ceanothus and dwarfed interior live oak may also predominate on such sites. Areas in which various kinds of chaparral communities are dominant include areas along Old Railroad Grade.[19]

Grassland areas are also common on Mount Tamalpais. Native perennial bunchgrass species were originally dominant, but most of these grasslands are now dominated by invasive annual grasses of European origin. Native grasslands, still found in a few isolated areas, are of two types. Northern coastal prairie is found below the fog line and is characterized by a Festuca-Danthonia association, while valley grassland, found in drier areas, is dominated by Nassella pulchra, with Elymus glaucus and Leymus triticoides also being common.[19]

Wetland vegetation types found on Mount Tamalpais include coastal riparian forests, wet meadows, and some marsh areas. Coastal riparian forest is predominant along the valley streams of Mount Tamalpais. Red and white alder (Alnus rubra and Alnus rhombifolia) and arroyo and yellow willow (Salix lasiolepis and S. lasiandra) are dominant in these types of woodland, with bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), box-elder (Acer negundo ssp. californicum), and California bay also being common.[19] Wet meadows are present in several high-elevation spots on the mountain,[20] while High Marsh represents a rare example of a marsh community on the mountain.

Serpentine soils have a high rate of endemism and are the site of several unique subtypes of the above plant communities. Serpentine grasslands are some of the few grasslands in which native perennial grasses are still relatively dominant. Serpentine chaparral forms a unique plant community, dominated by dwarfed leather oak (Quercus durata), Jepson ceanothus (Ceanothus jepsonii), Tamalpais manzanita (Arctostaphylos montana), and Sargent cypress (Cupressus sargentii). On the upper slopes of the mountain, small groves of Sargent cypress trees up to 50 feet (15 m) tall can be found in serpentine areas.[19]

Several species of endemic plants are found only on serpentine soils; these species may be widespread, but only occur on serpentine soils, or the may be more restricted, only growing in a few other places besides Mount Tamalpais, or may even be restricted just to Mount Tamalpais. The Mount Tamalpais thistle (Cirsium hydrophilum var. vaseyi), for example, is a rare variety of thistle known only from the serpentine seeps of the mountain.[21] The Mount Tamalpais jewelflower (Streptanthus batrachopus) is also limited to the area.

Wildlife

editMount Tamalpais provides one of the last remaining wildlife refuges in the Bay Area. Urbanization has invaded wildlife habitat, forcing many fauna in southern Marin County to retreat up onto Mount Tamalpais, Muir Woods, and the Bolinas Ridge. A wide variety of avifauna, amphibians, arthropods and mammals are found on Mount Tamalpais, including a number of rare and endangered species. Mt. Tamalpais and the neighboring Golden Gate Recreation Area together encompass over 115 square miles (298 square kilometers) of land, forming one of the largest preserved parklands located near a U.S. urban center.[citation needed]

History

editThe Coast Miwok are said to have believed that an evil witch dwelled at the top of Mount Tamalpais and therefore never set foot on the peak.[6]

Tamalpais was home to the Mount Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railway, also known as "The Crookedest Railroad in the World," a railroad which wound its way from downtown Mill Valley up to the mountain's East Peak, starting in 1896. An auto road was constructed to the peak as automobiles gained popularity in the 1920s. The 8-mile standard-gauge railroad used conventional rails but required mountain-climbing geared steam locomotives and operated from 1896 to 1930.[22][23]

Early wireless towers were constructed on the mountain in the early 20th century, only to be destroyed by one of the periodic hurricane-force windstorms.[citation needed]

In late November 1944, a US Navy plane crashed into the mountain after developing engine trouble shortly after takeoff from Alameda Naval Air Station. All eight aviators on board were killed.[24]

The U.S. Weather Bureau operated a weather station at the site of the now defunct Mill Valley Air Force Station for many years.

The peak and its surrounding areas are the birthplace of mountain biking in the 1970s, where early mountain bikers such as Gary Fisher, Charlie Kelly, and Joe Breeze were active.

British philosopher Alan Watts owned a cabin on Mount Tamalpais later in his life where he ultimately died in his sleep of heart failure on November 16, 1973.[25]

On top of the East Peak is a fire lookout station, staffed during the summer months by volunteers with the Marin County Fire Department.

Recreation

editMount Tamalpais is a hiking, picnicking, mountain and road cycling, horseback riding, and hang-gliding destination for residents of the San Francisco Bay Area, with over 100 miles (160 km) of trails and fire roads. With numerous trailheads, a well-networked trail and road system, and hikes of greatly varying length and difficulty, the mountain offers a compelling range of attractions. Marin Municipal Water District maintains several reservoirs on the north slopes of Mount Tamalpais, including Alpine Lake, Kent Lake, Bon Tempe Lake, Phoenix Lake, and Lake Lagunitas.

The western slopes of the mountain descend to the Pacific Ocean at Stinson Beach. The annual Dipsea Race traverses the mountain from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach. Though backpack camping isn't allowed, walk-in camping exists at the Pantoll and Bootjack campgrounds. The historic Bootjack Campground was established in the early 1920s by the Tamalpais Conservation Corps, and the Civilian Conservation Corps further refined the campground facilities in the 1930s. Showing substantial signs of overuse, the campground was closed by State Parks in 1969. The Bootjack Campground and Trail were reopened on Thursday, June 5, 2014.[26]

Trailhead parking within Mt. Tamalpais State Park is available generally with a self-service fee ($8). The scenic Ridgecrest Blvd. running along the ridgeline between the Rock Spring trailhead and Fairfax-Bolinas Road, with panoramic views of the summit, Pacific, San Francisco, Bolinas, and Point Reyes, is featured in many automobile and other advertisements, as well as being the local hang-gliding launch point. Mount Tam is also home to the Edgewood Botanic Garden and to the Sidney B. Cushing Amphitheatre where Broadway musical productions are performed every year by the Mountain Play Association. Monthly astronomy viewings and lectures are held at Rock Spring and Mountain Theater April through October by Mt Tam Astronomy.

Hiking and mountain biking

editSince the Mount Tamalpais area contains large expanses of undeveloped, natural land, there are many trails and trailheads that criss-cross the area. Many of these trails are used by hikers and bikers seeking refuge from the urban landscape of the San Francisco Bay Area.[citation needed] Some of these trails, including the mountaintop or ridgetop trails, have views of the San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean. Other trails, usually lower elevation valley trails, lead into natural, dense groves of mature Douglas-fir and redwood trees, clear, open grassland, and shrublands. All roads leading to the many trailheads around Mount Tamalpais are usually open, but during fire season some of these roads may be closed due to high fire risk.

The many roads, paved and unpaved, that cross the Mount Tamalpais region are used by mountain bikers, especially on weekends. Mount Tamalpais played an instrumental role in the birth of mountain biking many years ago, with pioneer frame builders such as Tom Ritchey, Gary Fisher, and Joe Breeze setting up shops in nearby towns. There has been considerable controversy over trail access for mountain bikes, both in terms of environmental impact and the safety of other trail users. As a result, bicycles have been banned from the majority of narrow, single-track trails, though bicycles are still allowed on fire roads. The fire roads on Mt. Tam are mixed-use and they are commonly used as running, hiking, biking and horseback riding routes.[27]

The Dipsea Race, the oldest cross-country trail running race in the U.S., is held in the area and part of the trail traverses the mountain from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach.[28]

Theater

editBroadway musicals are performed outdoors, several times each summer, in the stone open air Cushing Memorial Amphitheatre on the southern side of Mt. Tam.[29]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Mount Tamalpais, California". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ^ Skolnick, Sharon; Lustgarten, Bernie (1989). Dreams of Tamalpais. San Francisco, CA: Last Gasp of San Francisco Press. ISBN 978-0-86719-357-2.

- ^ Callaghan, Catherine. (1970). Bodega Miwok Dictionary. University of California Publications in Linguistics 60.

- ^ "Mt. Tamalpais" Archived 2006-12-21 at the Wayback Machine by Kathleen Goodwin, Point Reyes Visions.

- ^ a b Hill, Allison (June 1997). "Legends of Mount Tam". SFGate Get Outside! Blog. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 12, 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Miwok and Rancho Days". San Anselmo Historical Museum. San Anselmo Historical Society. November 11, 2006. Archived from the original on November 12, 2006.

- ^ Robertson, David. (1991). Mt. Tamalpais: The Legendary Birth of a Holy Mountain. California History 70(2):146–161.

- ^ Skolnick, Sharon. (1989). Dreams of Tamalpais. San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 0-86719-357-3

- ^ Billiter, Bill (January 1, 1985). "3,000-Year-Old Connection Claimed : Siberia Tie to California Tribes Cited". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2014-11-28. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

Another word with current Siberian translation, he said, is Tamalpais, the name of the mountain that is a landmark in the San Francisco Bay Area. "Pais" means place, he said, and "tamal" is a word used to describe one of the Siberian tribes.

- ^ "Mount Tamalpais-West Peak, California". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ^ "Mount Tamalpais State Park" (PDF). California State Parks. Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ Davidson, Keay (December 16, 2004). "Sinister quake hazard may lurk beneath Mount Tam". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ San Francisco State University SFSU Bay Area Rainfall Map

- ^ Worldclimate.com Rainfall station at about 950 feet (290 m) elevation.

- ^ Davidsanger.com Photograph of snow on Mount Tamalpais.

- ^ Graff, Amy (February 5, 2019). "That's not Tahoe: Mt. Tam looks like a winter wonderland after snow dusting". SFGate. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ Lee, Jack (February 27, 2023). "Photos show the Bay Area blanketed in rare snow". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ Sightseeingworld.com Archived 2007-02-13 at the Wayback Machine Climate description of the local area.

- ^ a b c d e f Shufford WD, Timossi IC. (1989). Plant Communities of Marin County. Sacramento, CA: California Native Plant Society. ISBN 0-943460-15-8

- ^ Howell JT. (1970). Marin Flora (2nd ed). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00578-3 ISBN 0-520-05621-3

- ^ "California Native Plant Society: Cirsium hydrophilum var. vaseyi". Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ The Mount Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railway Archived 2006-12-14 at the Wayback Machine (website) by Don Hargraves.

- ^ Wurm, Ted and Graves, Al. (1983). The Crookedest Railroad in the World. ISBN 0-87046-063-3

- ^ "Mount Tamalpais Aircraft Crash Site: Mill Valley, California". www.atlasobscura.com. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Brown, Patricia Leigh, "Oasis for Resisting Status Symbols Just Might Get One", New York Times, January 25, 2012. Date in 1973 and cause of death not specified in this source. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- ^ Bootjack Campground and Trail reopening parks.ca.gov [dead link]

- ^ "Single-Track Trail Mix" Archived 2004-11-04 at archive.today by Gordy Slack, California Wild 53:2, Spring 2000.

- ^ "The Dipsea Race".

- ^ Mountainplay.org: The Mountain Play Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

Further reading

edit- Fairley, Lincoln. (1987). Mount Tamalpais: A History. San Francisco: Scottwall Associates. ISBN 0-942087-00-3 (hardbound), ISBN 0-942087-01-1 (paperback)

- Spitz, Barry. (1998). Tamalpais Trails. San Anselmo, CA: Potrero Meadow Publishing Co. ISBN 0-9620715-2-8

- Skolnick, Sharon. (1989) Dreams of Tamalpais. San Francisco, CA: Last Gasp of San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-86719-357-2

External links

edit- Mount Tamalpais State Park – official site

- Mount Tamalpais Watershed – official site

- Friends of Mt Tam – official cooperating association of the state park

- About Mt. Tam – information the site of the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative

- SFAA Tam Star Parties Information on monthly star-gazing and lecture series.

Video and photographs

edit- A Day in the Life of a Fire Lookout on Mt. Tam's East Peak, video by Gary Yost

- The Invisible Peak, a short documentary about Mt. Tam's West Peak by Gary Yost

- Mt. Tamalpais Sunrise to Moonset, time-lapse video by Gary Yost

- 2010 - Timelapse of fog rolling around Mt. Tamalpais, more video by Gary Yost

- CA State Parks Photo Slideshow: Mount Tamalpais SP

Hiking and cycling

edit- Mount Tamalpais State Park, Marin County Visitors Bureau