This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2009) |

A porter, also called a bearer, is a person who carries objects or cargo for others. The range of services conducted by porters is extensive, from shuttling luggage aboard a train (a railroad porter) to bearing heavy burdens at altitude in inclement weather on multi-month mountaineering expeditions. They can carry items on their backs (backpack) or on their heads. The word "porter" derives from the Latin portare (to carry).[1]

The use of humans to transport cargo dates to the ancient world, prior to domesticating animals and development of the wheel. Historically it remained prevalent in areas where slavery was permitted, and exists today where modern forms of mechanical conveyance are impractical or impossible, such as in mountainous terrain, or thick jungle or forest cover.

Over time, slavery diminished and technology advanced, but the role of porter for specialized transporting services remains strong in the 21st century. Examples include bellhops at hotels, redcaps at railway stations, skycaps at airports, and bearers on adventure trips engaged by foreign travelers.

Expeditions

editPorters, frequently called Sherpas in the Himalayas (after the ethnic group most Himalayan porters come from), are also an essential part of mountaineering: they are typically highly skilled professionals who specialize in the logistics of mountain climbing, not merely people paid to carry loads (although carrying is integral to the profession). Frequently, porters/Sherpas work for companies who hire them out to climbing groups, to serve both as porters and as mountain guides; the term "guide" is often used interchangeably with "Sherpa" or "porter", but there are certain differences. Porters are expected to prepare the route before and/or while the main expedition climbs, climbing up beforehand with tents, food, water, and equipment (enough for themselves and for the main expedition), which they place in carefully located deposits on the mountain. This preparation can take months of work before the main expedition starts. Doing this involves numerous trips up and down the mountain, until the last and smallest supply deposit is planted shortly below the peak. When the route is prepared, either entirely or in stages ahead of the expedition, the main body follows. The last stage is often done without the porters, they remaining at the last camp, a quarter mile or below the summit, meaning only the main expedition is given the credit for mounting the summit. In many cases, since the porters are going ahead, they are forced to freeclimb, driving spikes and laying safety lines for the main expedition to use as they follow. Porters (such as Sherpas for example), are frequently local ethnic types, well adapted to living in the rarified atmosphere and accustomed to life in the mountains. Although they receive little glory, porters or Sherpas are often considered among the most skilled of mountaineers, and are generally treated with respect, since the success of the entire expedition is only possible through their work. They are also often called upon to stage rescue expeditions when a part of the party is endangered or there is an injury; when a rescue attempt is successful, several porters are usually called upon to transport the injured climber(s) back down the mountain so the expedition can continue. A well known incident where porters attempted to rescue numerous stranded climbers, and often died as a result, is the 2008 K2 disaster. Sixteen Sherpas were killed in the 2014 Mount Everest ice avalanche, inciting the entire Sherpa guide community to refuse to undertake any more ascents for the remainder of the year, making any further expeditions impossible.

History

editHuman adaptability and flexibility led to the early use of humans for transporting gear. Porters were commonly used as beasts of burden in the ancient world, when labor was generally cheap and slavery widespread. The ancient Sumerians, for example, enslaved women to shift wool and flax.

In the early Americas, where there were few native beasts of burden, all goods were carried by porters called Tlamemes in the Nahuatl language of Mesoamerica. In colonial times, some areas of the Andes employed porters called silleros to carry persons, particularly Europeans, as well as their luggage across the difficult mountain passes. Throughout the globe porters served, and in some areas continue to, as such littermen, particularly in crowded urban areas.

Many great works of engineering were created solely by muscle power in the days before machinery or even wheelbarrows and wagons; massive workforces of workers and bearers would complete impressive earthworks by manually lugging the earth, stones, or bricks in baskets on their backs.

Porters were very important to the local economies of many large cities in Brazil during the 1800s, where they were known as ganhadores. In 1857, ganhadores in Salvador, Bahia, went on strike in the first general strike in the country's history.[2]

Contribution to mountain climbing expeditions

editThe contributions of porters can often go overlooked. Amir Mehdi was a Pakistani mountaineer and porter known for being part of the team which managed the first successful ascent of Nanga Parbat in 1953, and of K2 in 1954 with an Italian expedition. He, along with the Italian mountaineer Walter Bonatti, are also known for having survived a night at the highest open bivouac - 8,100 metres (26,600 ft) - on K2 in 1954.[3] Fazal Ali, who was born in the Shimshal Valley in Pakistan North, is – according to the Guinness Book of World Records – the only man ever to have scaled K2 (8611 m) three times, in 2014, 2017 and 2018, all without oxygen, but his achievements have gone largely unrecognised.[4]

Today

editPorters are still paid to shift burdens in many third-world countries where motorized transport is impractical or unavailable, often alongside pack animals.

The Sherpa people of Nepal are so renowned as mountaineering porters that their ethnonym is synonymous with that profession. Their skill, knowledge of the mountains and local culture, and ability to perform at altitude make them indispensable for the highest Himalayan expeditions.

Porters at Indian railway stations are called coolies, a term for unskilled Asian labourer derived from the Chinese word for porter.

Mountain porters are also still in use in a handful of more developed countries, including Slovakia (horský nosič) and Japan (bokka, 歩荷). These men (and more rarely women) regularly resupply mountain huts and tourist chalets at high-altitude mountain ranges.[5][6][7][8]

In North America

editCertain trade-specific terms are used for forms of porters in North America, including bellhop (hotel porter), redcap (railway station porter), and skycap (airport porter).

The practice of railroad station porters wearing red-colored caps to distinguish them from blue-capped train personnel with other duties was begun on Labor Day of 1890 by an African-American porter in order to stand out from the crowds at Grand Central Terminal in New York City.[9] The tactic immediately caught on, over time adapted by other forms of porters for their specialties.[10]

Photos

edit-

An Indian Railways porter

-

Porters at a ford on the Sakawa River, near Odawara

-

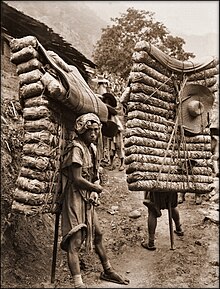

Nepali porters on Annapurna Circuit

-

Porter carrying luggage over a pedestrian bridge in Venice

-

Porter on Mount Kilimanjaro

-

Mountain and porters in Nepal

See also

edit- Head-carrying

- Kayayei (Ghanaian term for a female porter)

- Human-powered transport

- Land transport

- Portage

- Tumpline

References

edit- ^ The Concise Dictionary of English Etymology, p. 363

- ^ Reis, João José (May 1997). "'The Revolution of the Ganhadores': Urban Labour, Ethnicity and the African Strike of 1857 in Bahia, Brazil". Journal of Latin American Studies. 29 (2). Translated by H. Sabrina Gledhill. Cambridge University Press: 355–393. doi:10.1017/S0022216X9700477X. JSTOR 158398. S2CID 55955013.

- ^ "Bonatti e il K2, la vera storia". nationalgeographic.it. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ hermesauto (2018-11-04). "Foreign climbers claim the glory, but Pakistani porters remain the unsung masters of the mountains". The Straits Times. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- ^ Slovak mountain porters are a dying breed. The Slovak Spectator. Spectator.sme.sk. 30 June 2008.

- ^ Article with news on Slovak mountain porters. The Slovak Spectator. Spectator.sme.sk. 30 June 2008.

- ^ Sloboda pod nákladom. Trailer for a documentary on the Slovak mountain porter tradition, by Pavol Barabáš and K2 Studio. K2 Studio official Vimeo account.

- ^ Japanese mountain chalet porter Masato Hagiwara in action. YouTube.com. 28 September 2018.

- ^ Drake, St. Clair; Cayton, Horace R. (1970). Black Metropolis. University of Chicago Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-226-16234-8.

- ^ Railway Progress. 1950. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Herinneringen aan Japan, 1850–1870: Foto's en Fotoalbums in Nederlands Bezit ('s-Gravenhage : Staatsuitgeverij, 1987), pp. 106–107, repr.

- New York Public Library, s.v. "Beato, Felice", cited 21 June 2006.