The myenteric plexus (or Auerbach's plexus) provides motor innervation to both layers of the muscular layer of the gut, having both parasympathetic and sympathetic input (although present ganglion cell bodies belong to parasympathetic innervation, fibers from sympathetic innervation also reach the plexus), whereas the submucous plexus provides secretomotor innervation to the mucosa nearest the lumen of the gut.

| Myenteric plexus | |

|---|---|

The myenteric plexus from the rabbit. X 50. | |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | plexus myentericus, plexus Auerbachi |

| MeSH | D009197 |

| TA98 | A14.3.03.041 |

| TA2 | 6727 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

It arises from cells in the vagal trigone also known as the nucleus ala cinerea, the parasympathetic nucleus of origin for the tenth cranial nerve (vagus nerve), located in the medulla oblongata. The fibers are carried by both the anterior and posterior vagal nerves. The myenteric plexus is the major nerve supply to the gastrointestinal tract and controls GI tract motility.[1]

According to preclinical studies, 30% of myenteric plexus' neurons are enteric sensory neurons, thus Auerbach's plexus has also a sensory component.[2][3]

Structure

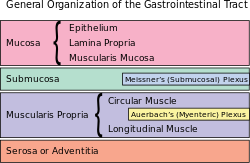

editA part of the enteric nervous system, the myenteric plexus exists between the longitudinal and circular layers of muscularis externa in the gastrointestinal tract. It is found in the muscles of the esophagus, stomach, and intestine.[citation needed]

The ganglia have properties similar to the central nervous system (CNS). These properties include presence of glia, interneurons, a small extracellular space, dense synaptic neuropil, isolation from blood vessels, multiple synaptic mechanisms and multiple neurotransmitters.

The myenteric plexus originates in the medulla oblongata as a collection of neurons from the ventral part of the brain stem. The vagus nerve then carries the axons to their destination in the gastrointestinal tract.[4]

They contain Dogiel cells.[5]

Function

editThe myenteric plexus functions as a part of the enteric nervous system (digestive system). The enteric nervous system can and does function autonomously, but normal digestive function requires communication links between this intrinsic system and the central nervous system. The ENS contains sensory receptors, primary afferent neurons, interneurons, and motor neurons. The events that are controlled, at least in part, by the ENS are multiple and include motor activity, secretion, absorption, blood flow, and interaction with other organs such as the gallbladder or pancreas. These links take the form of parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers that connect either the central and enteric nervous systems or connect the central nervous system directly with the digestive tract. Through these cross connections, the gut can provide sensory information to the CNS, and the CNS can affect gastrointestinal function. Connection to the central nervous system also means that signals from outside of the digestive system can be relayed to the digestive system: for instance, the sight of appealing food stimulates secretion in the stomach.[6]

Neurotransmitters

editThe enteric nervous system makes use of over 30 different neurotransmitters, most similar to those of the CNS such as acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin. More than 90% of the body's serotonin lies in the gut; as well as about 50% of the body's dopamine, which is currently being studied to further our understanding of its utility in the brain.[7] The heavily studied neuropeptide known as substance P is present in significant levels and may help facilitate the production of saliva, smooth muscle contractions, and other tissue responses.

Receptors

editSince many of the same neurotransmitters are found in the ENS as the brain, it follows that myenteric neurons can express receptors for both peptide and non-peptide (amines, amino acids, purines) neurotransmitters. Generally, expression of a receptor is limited to a subset of myenteric neurons, with probably the only exception being expression of nicotinic cholinergic receptors on all myenteric neurons. One receptor that has been targeted for therapeutic reasons has been the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT4) receptor. Activating this pre-synaptic receptor enhances cholinergic neurotransmission and can stimulate gastrointestinal motility.[8]

The enteric nervous system exhibits taste receptors similar to the ones in the tongue. The taste receptor TAS1R3 and the taste G protein gustducin are two of the most common. These receptors sense "sweetness" on the tongue and sense glucose in the enteric nervous system. These receptors help regulate the secretion of insulin and other hormones that are responsible for controlling blood sugar levels.[9]

Clinical significance

editHirschsprung's disease is a congenital disorder of the colon in which nerve cells of the myenteric plexus in its walls, also known as ganglion cells, are absent. Hirschsprung's disease is a form of functional low bowel obstruction due to failure of caudal migration of neuroblasts within developing bowel – this results in an absence of parasympathetic intrinsic ganglion cells in both Auerbach's and Meissner's plexuses. The distal large bowel from the point of neuronal arrest to the anus is continuously aganglionic. It is a rare disorder (1:5000), with prevalence among males being four times that of females.[10]

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus characterized by decrease in ganglion cell density in the myenteric plexus. The cause of the lesion is unknown.[11]

Myenteric plexi destruction has been found to be secondary to Chagas disease (T. cruzi infection sequelae). Destruction occurs in the esophagus, intestines, and ureters. This denervation can lead to secondary achalasia (lower esophageal sphincter will not open; loss of inhibitory neurons), megacolon, and megaureter, respectively.

Role in CNS disorders

editBecause the ENS is known as the "brain of the gut", due to its similarities with the CNS, researchers have been using colonic biopsies of Parkinson's patients to help better understand and manage Parkinson's disease.[12] PD patients are known to experience severe constipation due to GI tract dysfunction years before the onset of motor movement complications, which characterises Parkinson's disease.[13]

History

editLeopold Auerbach, a neuropathologist, was one of the first to further research the nervous system using histological staining methods.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ Human Anatomy and Physiology, Marieb & Hoehn, seventh edition[page needed]

- ^ Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Vol. 194: Sensory Nerves, Brendan J. Canning, Domenico Spina. Springer. Page 341.

- ^ Costa, M; Brookes, S. J.; Hennig, G. W. (2000). "Anatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous system". Gut. 47 (90004): iv15–9, discussion iv26. doi:10.1136/gut.47.suppl_4.iv15. PMC 1766806. PMID 11076898.

- ^ Mazzuoli, Gemma; Schemann, Michael (2012). "Mechanosensitive Enteric Neurons in the Myenteric Plexus of the Mouse Intestine". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e39887. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...739887M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039887. PMC 3388088. PMID 22768317.

- ^ Stach, W (1979). "Differentiated vascularization of Dogiel's cell types and the preferred vascularization of type I/2 cells within plexus myentericus (Auerbach) ganglia of the pig (author's transl)". Anatomischer Anzeiger. 145 (5): 464–73. PMID 507375.

- ^ Fujita, Shin; Nakanisi, Yukihiro; Taniguchi, Hirokazu; Yamamoto, Seiichiro; Akasu, Takayuki; Moriya, Yoshihiro; Shimoda, Tadakazu (2007). "Cancer Invasion to Auerbachʼs Plexus is an Important Prognostic Factor in Patients with pT3-pT4 Colorectal Cancer". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 50 (11): 1860–6. doi:10.1007/s10350-007-9072-8. PMID 17899273. S2CID 26109259.

- ^ Pasricha, Pankaj Jay (2 March 2011). "Stanford Hospital: Brain in the Gut - Your Health". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22.

- ^ Dickson, E. J.; Heredia, D. J.; Smith, T. K. (2010). "Critical role of 5-HT1A, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptor subtypes in the initiation, generation, and propagation of the murine colonic migrating motor complex". AJP: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 299 (1): G144–57. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00496.2009. PMC 2904117. PMID 20413719.

- ^ Margolskee, Robert F.; Dyer, Jane; Kokrashvili, Zaza; Salmon, Kieron S. H.; Ilegems, Erwin; Daly, Kristian; Maillet, Emeline L.; Ninomiya, Yuzo; Mosinger, Bedrich; Shirazi-Beechey, Soraya P. (2007). "T1R3 and gustducin in gut sense sugars to regulate expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter 1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (38): 15075–80. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415075M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706678104. JSTOR 25449086. PMC 1986615. PMID 17724332.

- ^ Tam, Paul K. H.; Garcia-Barceló, Mercè (2009). "Genetic basis of Hirschsprung's disease". Pediatric Surgery International. 25 (7): 543–58. doi:10.1007/s00383-009-2402-2. PMID 19521704. S2CID 27343466.

- ^ Storch, W. B.; Eckardt, V. F.; Wienbeck, M; Eberl, T; Auer, P. G.; Hecker, A; Junginger, T; Bosseckert, H (1995). "Autoantibodies to Auerbach's plexus in achalasia". Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France). 41 (8): 1033–8. PMID 8747084.

- ^ Shprecher, D. R.; Derkinderen, P. (2012). "Parkinson Disease: The Enteric Nervous System Spills its Guts". Neurology. 78 (9): 683, author reply 683. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824bd195. PMID 22371415.

- ^ Lebouvier, Thibaud; Neunlist, Michel; Bruley Des Varannes, Stanislas; Coron, Emmanuel; Drouard, Anne; n'Guyen, Jean-Michel; Chaumette, Tanguy; Tasselli, Maddalena; Paillusson, Sébastien; Flamand, Mathurin; Galmiche, Jean-Paul; Damier, Philippe; Derkinderen, Pascal (2010). "Colonic Biopsies to Assess the Neuropathology of Parkinson's Disease and Its Relationship with Symptoms". PLOS ONE. 5 (9): e12728. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512728L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012728. PMC 2939055. PMID 20856865.

External links

edit- Slide at ucla.edu

- Histology image: 49_09 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- Histology image: 21703loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 885