TAH molecule, also known as N-acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamate peptidase I (NAALADase I), NAAG peptidase, or prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the FOLH1 (folate hydrolase 1) gene.[5] Human GCPII contains 750 amino acids and weighs approximately 84 kDa.[6]

| FOLH1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | FOLH1, FGCP, FOLH, GCP2, GCPII, NAALAD1, NAALAdase, PSM, PSMA, mGCP, folate hydrolase (prostate-specific membrane antigen) 1, folate hydrolase 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 600934; MGI: 1858193; HomoloGene: 136782; GeneCards: FOLH1; OMA:FOLH1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TAH molecule | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reaction Scheme of NAAG Degradation by GCPII: GCPII + NAAG → GCPII-NAAG complex → Glutamate + NAA | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 3.4.17.21 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 111070-04-3 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

GCPII is a zinc metalloenzyme that resides in membranes. Most of the enzyme resides in the extracellular space. GCPII is a class II membrane glycoprotein. It catalyzes the hydrolysis of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) to glutamate and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) according to the reaction scheme to the right.[7][8]

Neuroscientists primarily use the term NAALADase in their studies, while those studying folate metabolism use folate hydrolase, and those studying prostate cancer or oncology, PSMA. All refer to the same protein glutamate carboxypeptidase II.

Discovery

editGCPII is mainly expressed in four tissues of the body, including prostate epithelium, the proximal tubules of the kidney, the jejunal brush border of the small intestine and ganglia of the nervous system.[6][9][10]

Indeed, the initial cloning of the cDNA encoding the gene expressing PSMA was accomplished with RNA from a prostate tumor cell line, LNCaP. PSMA was first detected in the LNCaP cell line using the murine monoclonal antibody 7E11-C5.3 (also known by the name capromab), generated from murine spleen cells treated with LNCaP cell membranes. However, 7E11-C5.3 exclusively targets an intracellular epitope of PSMA, thus only binding to dead or dying cells.[11][12] PSMA shares homology with the transferrin receptor and undergoes endocytosis but the ligand for inducing internalization has not been identified.[13] It was found that PSMA was the same as the membrane protein in the small intestine responsible for removal of gamma-linked glutamates from polygammaglutamate folate. This enables the freeing of folic acid, which then can be transported into the body for use as a vitamin. This resulted in the cloned genomic designation of PSMA as FOLH1 for folate hydrolase.[14]

- PSMA(FOLH1) + folate polygammaglutamate(n 1-7) → PSMA (FOLH1) + folate(poly)gammaglutamate(n-1) + glutamate continuing until releasing folate.

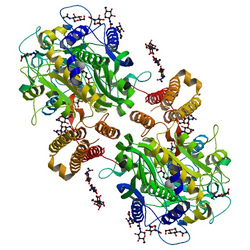

Structure

editThe three domains of the extracellular portion of GCPII—the protease, apical and C-terminal domains—collaborate in substrate recognition.[8] The protease domain is a central seven-stranded mixed β-sheet. The β-sheet is flanked by 10 α-helices. The apical domain is located between the first and the second strands of the central β-sheet of the protease domain. The C-terminal domain is an Up-Down-Up-Down four-helix bundle.[8] The apical, protease and C-terminal domains create a pocket that facilitates substrate binding.[15]: 14

The central pocket is approximately 2 nanometers in depth and opens from the extracellular space to the active site.[8] This active site contains two zinc ions. During inhibition, each acts as a ligand to an oxygen in 2-PMPA or phosphate. There is also one calcium ion coordinated in GCPII, far from the active site. It has been proposed that calcium holds together the protease and apical domains.[8] In addition, human GCPII has ten sites of potential glycosylation, and many of these sites (including some far from the catalytic domain) affect the ability of GCPII to hydrolyze NAAG.[6]

The human FOLH1 gene is positioned at the 11p11.12 locus of chromosome 11. The gene is 4,110 base pairs in length and composed of 22 exons. The encoded protein is a member of the M28 peptidase family. Orthologs of the human FOLH1 gene have also been identified in other mammals, including the 7 D3; 7 48.51 cM locus in mice.[16] The FOLH1 gene has multiple potential start sites and splice forms, giving rise to differences in membrane protein structure, localization, and carboxypeptidase activity based on the parent tissue.[6][17]

Enzyme kinetics

editThe hydrolysis of NAAG by GCPII obeys Michaelis–Menten kinetics.[15] Hlouchková et al. (2007) determined the Michaelis constant (Km) for NAAG to be 1.2*10−6 ± 0.5*10−6 M and the turnover number (kcat) to be 1.1 ± 0.2 s−1.[18]

Role in cancer

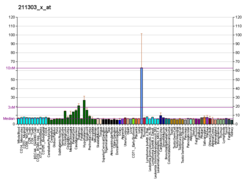

editHuman PSMA is highly expressed in the prostate, roughly a hundred times greater than in most other tissues. In some prostate cancers, PSMA is the second-most upregulated gene product, with an 8- to 12-fold increase over levels in noncancerous prostate cells.[19] Because of this high expression, PSMA is being developed as potential biomarker for therapy and imaging of some cancers.[20] In human prostate cancer, the higher expressing tumors are associated with quicker time to progression and a greater percentage of patients suffering relapse.[21][22] In vitro studies using prostate and breast cancer cell lines with decreased PSMA levels showed a significant decrease in the proliferation, migration, invasion, adhesion and survival of the cells.[23]

Imaging

editPSMA is the target of several nuclear medicine imaging agents for prostate cancer. PSMA expression can be imaged with gallium-68 PSMA or fluorine-18 PSMA for positron emission tomography.[24][25][26][27] This uses a radiolabelled small molecule that binds with high affinity to the extra-cellular domain of the PSMA receptor. Previously, an antibody targeting the intracellular domain (indium-111 capromabpentide, marketed as Prostascint) was used,[28] although detection rate was low.

In 2020, the results of a randomised phase 3 trial ("ProPSMA study")[29] was published comparing Gallium-68 PSMA PET/CT to standard imaging (CT and bone scan). This 300 patient study conducted at 10 study sites demonstrated superior accuracy of PSMA PET/CT (92% vs 65%), higher significant change in management (28% vs 15%), less equivocal/uncertain imaging findings (7% vs 23%) and lower radiation exposure (10 mSv vs 19 mSv). The study concludes that PSMA PET/CT is a suitable replacement for conventional imaging, providing superior accuracy, to the combined findings of CT and bone scanning. This new technology was approved by the FDA on Dec 1, 2020.[30] A dual-modality small molecule that is positron-emitting (18F) and fluorescent targets PSMA and was tested in humans. The molecule found the location of primary and metastatic prostate cancer by PET, fluorescence-guided removal of cancer, and detects single cancer cells in tissue margins.[31]

A Human-Derived, Genetic, Positron-emitting and Fluorescent (HD-GPF) reporter system uses a human protein, PSMA and non-immunogenic, and a small molecule that is positron-emitting (18F) and fluorescent for dual modality PET and fluorescence imaging of genome modified cells, e.g. cancer, CRISPR/Cas9, or CAR T-cells, in an entire mouse.[32]

Therapy

editPSMA can also be used as a target for treatment in unsealed source radiotherapy. Lutetium-177 is a beta emitter which can be combined with PSMA-targeting molecules to deliver treatment to prostate tumours.[33] A prospective phase II study demonstrated a response (as defined by reduction in PSA of 50% or more) in 64% of men.[34] Common side effects include dry mouth, dry fatigue, nausea, dry eyes and thrombocytopenia (reduction in platelets). A follow-up randomized phase II trial, the ANZUP TheraP trial, compared Lu-177 PSMA-617 radionuclide therapy to cabazitaxel chemotherapy, demonstrating superior response rates, lower toxicity and better patient-reported outcomes with Lu-177 PSMA(PMID 33581798). The results of randomised trial VISION trial were positive with 40% reduction in mortality and 5 months increase in survival. phase III VISION trial.[35][36]

Neurotransmitter degradation

editFor those studying neural based diseases, NAAG is one of the three most prevalent neurotransmitters found in the central nervous system[37] and when it catalyzes the reaction to produce glutamate it is also producing another neurotransmitter.[8] Glutamate is a common and abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system; however, if there is too much glutamate transmission, this can kill or at least damage neurons and has been implicated in many neurological diseases and disorders[37] therefore the balance that NAAG peptidase contributes to is quite important.

Potential therapeutic applications

editFunction in the brain

editGCPII has been shown to both indirectly and directly increase the concentration of glutamate in the extracellular space.[37] GCPII directly cleaves NAAG into NAA and glutamate.[7][8] NAAG has been shown, in high concentration, to indirectly inhibit the release of neurotransmitters, such as GABA and glutamate. It does this through interaction with and activation of presynaptic group II mGluRs.[37] Thus, in the presence of NAAG peptidase, the concentration of NAAG is kept in check, and glutamate and GABA, among other neurotransmitters, are not inhibited.

Researchers have been able to show that effective and selective GCPII inhibitors are able to decrease the brain's levels of glutamate and even provide protection from apoptosis or degradation of brain neurons in many animal models of stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and neuropathic pain.[8] This inhibition of these NAAG peptidases, sometimes referred to as NPs, are thought to provide this protection from apoptosis or degradation of brain neurons by elevating the concentrations of NAAG within the synapse of neurons.[37] NAAG then reduces the release of glutamate while stimulating the release of some trophic factors from the glia cells in the central nervous system, resulting in the protection from apoptosis or degradation of brain neurons.[37] It is important to note, however, that these NP inhibitors do not seem to have any effect on normal glutamate function.[37] The NP inhibition is able to improve the naturally occurring regulation instead of activating or inhibiting receptors that would disrupt this process.[37] Research has also shown that small-molecule-based NP inhibitors are beneficial in animal models that are relevant to neurodegenerative diseases.[37] Some specific applications of this research include neuropathic and inflammatory pain, traumatic brain injury, ischemic stroke, schizophrenia, diabetic neuropathy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as drug addiction.[37] Previous research has found that drugs that are able to reduce glutamate transmission can relieve the neuropathic pain, although the resultant side-effects have limited a great deal of their clinical applications.[38] Therefore, it appears that, since GCPII is exclusively recruited for the purpose of providing a glutamate source in hyperglutamatergic and excitotoxic conditions, this could be an alternative to avert these side-effects.[38] More research findings have shown that the hydrolysis of NAAG is disrupted in schizophrenia, and they have shown that specific anatomical regions of the brain may even show discrete abnormalities in the GCP II synthesis, so NPs may also be therapeutic for patients suffering with schizophrenia.[39] One major hurdle with using many of the potent GCPII inhibitors that have been prepared to date are typically highly polar compounds, which causes problems because they do not then penetrate the blood–brain barrier easily.[40]

Potential uses of NAAG peptidase inhibitors

editGlutamate is the “primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the human nervous system”,[37] participating in a multitude of brain functions. Overstimulation and -activation of glutamate receptors as well as “disturbances in the cellular mechanisms that protect against the adverse consequences of physiological glutamate receptor activation”[40] have been known to cause neuron damage and death, which have been associated with multiple neurological diseases.[37]

Due to the range of glutamate function and presence, it has been difficult to create glutamatergic drugs that do not negatively affect other necessary functions and cause unwanted side-effects.[41] NAAG peptidase inhibition has offered the possibility for specific drug targeting.

Specific inhibitors

editSince its promise for possible neurological disease therapy and specific drug targeting, NAAG peptidase inhibitors have been widely created and studied. A few small molecule examples are those that follow:[37]

- 2-PMPA and analogues

- Thiol and indole thiol derivatives

- Hydroxamate derivatives

- Conformationally constricted dipeptide mimetics

- PBDA- and urea-based inhibitors.

Other potential therapeutic applications

editNeuropathic and inflammatory pain

editPain cause by injury to CNS or PNS has been associated with increase glutamate concentration. NAAG inhibition reduced glutamate presence and could, thus, diminish pain.[37] (Neale JH et al., 2005). Nagel et al.[41] used the inhibitor 2-PMPA to show the analgesic effect of NAAG peptidase inhibitions. This study followed one by Chen et al.,[42] which showed similar results.[41]

Head injury

editSevere head injury (SHI) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) are widespread and have a tremendous impact. “They are the leading cause of death in children and young adults (<25 years) and account for a quarter of all deaths in the five to 15 years age group”.[43] Following initial impact, glutamate levels rise and cause excitotoxic damage in a process that has been well characterized.[37] With its ability to reduce glutamate levels, NAAG inhibition has shown promise in preventing neurological damage associated with SHI and TBI.

Stroke

editAccording to the National Stroke Association,[44] stroke is the third-leading cause of death and the leading cause of adult disability. It is thought that glutamate levels cause underlying ischemic damage during a stroke, and, thus, NAAG inhibition might be able to diminish this damage.[37]

Schizophrenia

editSchizophrenia is a mental disorder that affects 1% of people throughout the world.[45] It can be modeled by PCP in laboratory animals, and it has been shown that mGluR agonists have reduced the effects of the drug. NAAG is such an mGluR agonist. Thus, inhibition of the enzyme that reduces NAAG concentration, NAAG peptidase, could provide a practical treatment for reduction of schizophrenic symptoms.[37]

Diabetic neuropathy

editDiabetes can lead to damaged nerves, causing loss of sensation, pain, or, if autonomic nerves are associated, damage to the circulatory, reproductive, or digestive systems, among others. Over 60% of diabetic patients are said to have some form of neuropathy,[37] however, the severity ranges dramatically. Neuropathy not only directly causes harm and damage but also can indirectly lead to such problems as diabetic ulcerations, which in turn can lead to amputations. In fact, over half of all lower limb amputations in the United States are of patients with diabetes.[46]

Through the use of the NAAG peptidase inhibitor 2-PMPA, NAAG cleavage was inhibited and, with it, programmed DRG neuronal cell death in the presence of high glucose levels.[47] The researchers have proposed that the cause of this is NAAG's agonistic activity at mGluR3. In addition, NAAG also “prevented glucose-induced inhibition of neurite growth” (Berent- Spillson, et al. 2004). Overall, this makes GCPIII inhibition a clear model target for combating diabetic neuropathy.

Drug addiction

editSchizophrenia, as previously described, is normally modeled in the laboratory through a PCP animal model. As GCPIII inhibition was shown to possibly limit schizophrenic behavior in this model,[37] this suggests that GCPIII inhibition, thus, reduces the effect of PCP. In addition, the reward action of many drugs (cocaine, PCP, alcohol, nicotine, etc.) have been shown with increasing evidence to be related to glutamate levels, on which NAAG and GCPIII can have some regulatory effect.[37]

In summary, the findings of multiple drug studies to conclude that:[37]

- NAAG/NP system might be involved in neuronal mechanisms regulating cue-induced cocaine craving, the development of cocaine seizure kindling, and management of opioid addiction and alcohol consumptive behaviour. Therefore, NP inhibitors could provide a novel therapy for such conditions.

Other diseases and disorders

editNAAG inhibition has also been studied as a treatment against prostate cancer, ALS, and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease.[37]

References

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000086205 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000001773 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ O'Keefe DS, Su SL, Bacich DJ, Horiguchi Y, Luo Y, Powell CT, et al. (November 1998). "Mapping, genomic organization and promoter analysis of the human prostate-specific membrane antigen gene". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression. 1443 (1–2): 113–127. doi:10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00200-0. PMID 9838072.

- ^ a b c d Barinka C, Sácha P, Sklenár J, Man P, Bezouska K, Slusher BS, Konvalinka J (June 2004). "Identification of the N-glycosylation sites on glutamate carboxypeptidase II necessary for proteolytic activity". Protein Science. 13 (6): 1627–1635. doi:10.1110/ps.04622104. PMC 2279971. PMID 15152093.

- ^ a b Rojas C, Frazier ST, Flanary J, Slusher BS (November 2002). "Kinetics and inhibition of glutamate carboxypeptidase II using a microplate assay". Analytical Biochemistry. 310 (1): 50–54. doi:10.1016/S0003-2697(02)00286-5. PMID 12413472.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mesters JR, Barinka C, Li W, Tsukamoto T, Majer P, Slusher BS, et al. (March 2006). "Structure of glutamate carboxypeptidase II, a drug target in neuronal damage and prostate cancer". The EMBO Journal. 25 (6): 1375–1384. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600969. PMC 1422165. PMID 16467855.

- ^ Sácha P, Zámecník J, Barinka C, Hlouchová K, Vícha A, Mlcochová P, et al. (February 2007). "Expression of glutamate carboxypeptidase II in human brain". Neuroscience. 144 (4): 1361–1372. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.022. PMID 17150306. S2CID 45351503.

- ^ Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Zhang S, Terracciano L, Sauter G, Chadhuri A, Herrmann FR, Penetrante R (March 2007). "Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) protein expression in normal and neoplastic tissues and its sensitivity and specificity in prostate adenocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical study using multiple tumour tissue microarray technique". Histopathology. 50 (4): 472–483. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02635.x. PMID 17448023. S2CID 23454712.

- ^ Troyer, John K.; Feng, Qi; Beckett, Mary Lou; Wright, George L. (January 1995). "Biochemical characterization and mapping of the 7E11-C5.3 epitope of the prostate-specific membrane antigen". Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 1 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1016/1078-1439(95)00004-2. PMID 21224087.

- ^ Israeli RS, Powell CT, Fair WR, Heston WD (January 1993). "Molecular cloning of a complementary DNA encoding a prostate-specific membrane antigen". Cancer Research. 53 (2): 227–230. PMID 8417812.

- ^ Goodman OB, Barwe SP, Ritter B, McPherson PS, Vasko AJ, Keen JH, et al. (November 2007). "Interaction of prostate specific membrane antigen with clathrin and the adaptor protein complex-2". International Journal of Oncology. 31 (5): 1199–1203. doi:10.3892/ijo.31.5.1199. PMID 17912448.

- ^ Pinto JT, Suffoletto BP, Berzin TM, Qiao CH, Lin S, Tong WP, et al. (September 1996). "Prostate-specific membrane antigen: a novel folate hydrolase in human prostatic carcinoma cells". Clinical Cancer Research. 2 (9): 1445–1451. PMID 9816319.

- ^ a b Rakhimbekova A (2021). Structure-assisted development of a continuous carboxypeptidase assay (PDF) (Diploma thesis). Prague: Charles University. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Folh1 folate hydrolase 1 [Mus musculus (house mouse)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ O'Keefe DS, Bacich DJ, Heston WD (2001). "Prostate Specific Membraen Antigen". In Simons JW, Chung LW, Isaacs WB (eds.). Prostate cancer: biology, genetics and the new therapeutics. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 307–326. ISBN 978-0-89603-868-4.

- ^ Hlouchová K, Barinka C, Klusák V, Sácha P, Mlcochová P, Majer P, et al. (May 2007). "Biochemical characterization of human glutamate carboxypeptidase III". Journal of Neurochemistry. 101 (3): 682–696. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04341.x. PMID 17241121.

- ^ O'Keefe DS, Bacich DJ, Heston WD (February 2004). "Comparative analysis of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) versus a prostate-specific membrane antigen-like gene". The Prostate. 58 (2): 200–210. doi:10.1002/pros.10319. PMID 14716746. S2CID 25780520.

- ^ Wang X, Yin L, Rao P, Stein R, Harsch KM, Lee Z, Heston WD (October 2007). "Targeted treatment of prostate cancer". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 102 (3): 571–579. doi:10.1002/jcb.21491. PMID 17685433. S2CID 46594564.

- ^ Perner S, Hofer MD, Kim R, Shah RB, Li H, Möller P, et al. (May 2007). "Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression as a predictor of prostate cancer progression". Human Pathology. 38 (5): 696–701. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2006.11.012. PMID 17320151.

- ^ Ross JS, Sheehan CE, Fisher HA, Kaufman RP, Kaur P, Gray K, et al. (December 2003). "Correlation of primary tumor prostate-specific membrane antigen expression with disease recurrence in prostate cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (17): 6357–6362. PMID 14695135.

- ^ Zhang Y, Guo Z, Du T, Chen J, Wang W, Xu K, et al. (June 2013). "Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA): a novel modulator of p38 for proliferation, migration, and survival in prostate cancer cells". The Prostate. 73 (8): 835–841. doi:10.1002/pros.22627. PMID 23255296. S2CID 35257177.

- ^ Maurer T, Eiber M, Schwaiger M, Gschwend JE (April 2016). "Current use of PSMA-PET in prostate cancer management". Nature Reviews. Urology. 13 (4): 226–235. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2016.26. PMID 26902337. S2CID 2448922.

- ^ Fendler WP, Eiber M, Beheshti M, Bomanji J, Ceci F, Cho S, et al. (June 2017). "68Ga-PSMA PET/CT: Joint EANM and SNMMI procedure guideline for prostate cancer imaging: version 1.0". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 44 (6): 1014–1024. doi:10.1007/s00259-017-3670-z. PMID 28283702. S2CID 5882407.

- ^ Ekmekcioglu Ö, Busstra M, Klass ND, Verzijlbergen F (October 2019). "Bridging the Imaging Gap: PSMA PET/CT Has a High Impact on Treatment Planning in Prostate Cancer Patients with Biochemical Recurrence-A Narrative Review of the Literature". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 60 (10): 1394–1398. doi:10.2967/jnumed.118.222885. PMID 30850500.

- ^ Zippel C, Ronski SC, Bohnet-Joschko S, Giesel FL, Kopka K (January 2020). "Current Status of PSMA-Radiotracers for Prostate Cancer: Data Analysis of Prospective Trials Listed on ClinicalTrials.gov". Pharmaceuticals. 13 (1): E12. doi:10.3390/ph13010012. PMC 7168903. PMID 31940969.

- ^ Virgolini I, Decristoforo C, Haug A, Fanti S, Uprimny C (March 2018). "Current status of theranostics in prostate cancer". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 45 (3): 471–495. doi:10.1007/s00259-017-3882-2. PMC 5787224. PMID 29282518.

- ^ Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJ, Tang C, Vela I, Thomas P, et al. (April 2020). "Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study". Lancet. 395 (10231): 1208–1216. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30314-7. PMID 32209449. S2CID 214609500.

- ^ "FDA Approves First PSMA-Targeted PET Imaging Drug for Men with Prostate Cancer". fda.gov. 1 December 2020.

- ^ Aras O, Demirdag C, Kommidi H, Guo H, Pavlova I, Aygun A, et al. (October 2021). "Small Molecule, Multimodal, [18F]-PET and Fluorescence Imaging Agent Targeting Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen: First-in-Human Study". Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. 19 (5): 405–416. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2021.03.011. PMC 8449790. PMID 33879400.

- ^ Guo H, Kommidi H, Vedvyas Y, McCloskey JE, Zhang W, Chen N, et al. (July 2019). "A Fluorescent, [18F]-Positron-Emitting Agent for Imaging Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Allows Genetic Reporting in Adoptively Transferred, Genetically Modified Cells". ACS Chemical Biology. 14 (7): 1449–1459. doi:10.1021/acschembio.9b00160. PMC 6775626. PMID 31120734.

- ^ Emmett L, Willowson K, Violet J, Shin J, Blanksby A, Lee J (March 2017). "Lutetium 177 PSMA radionuclide therapy for men with prostate cancer: a review of the current literature and discussion of practical aspects of therapy". Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences. 64 (1): 52–60. doi:10.1002/jmrs.227. PMC 5355374. PMID 28303694.

- ^ Violet J, Sandhu S, Iravani A, Ferdinandus J, Thang SP, Kong G, et al. (June 2020). "Long-Term Follow-up and Outcomes of Retreatment in an Expanded 50-Patient Single-Center Phase II Prospective Trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Theranostics in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 61 (6): 857–865. doi:10.2967/jnumed.119.236414. PMC 7262220. PMID 31732676.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT03511664 for "VISION: An International, Prospective, Open Label, Multicenter, Randomized Phase 3 Study of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in the Treatment of Patients With Progressive PSMA-positive Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Wester HJ, Schottelius M (July 2019). "PSMA-Targeted Radiopharmaceuticals for Imaging and Therapy". Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 49 (4): 302–312. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2019.02.008. PMID 31227053. S2CID 155790848.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Zhou J, Neale JH, Pomper MG, Kozikowski AP (December 2005). "NAAG peptidase inhibitors and their potential for diagnosis and therapy". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 4 (12): 1015–1026. doi:10.1038/nrd1903. PMID 16341066. S2CID 21807952.

- ^ a b Zhang W, Murakawa Y, Wozniak KM, Slusher B, Sima AA (September 2006). "The preventive and therapeutic effects of GCPII (NAALADase) inhibition on painful and sensory diabetic neuropathy". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 247 (2): 217–223. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.052. PMID 16780883. S2CID 11547550.

- ^ Ghose S, Weickert CS, Colvin SM, Coyle JT, Herman MM, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE (January 2004). "Glutamate carboxypeptidase II gene expression in the human frontal and temporal lobe in schizophrenia". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300304. PMID 14560319.

- ^ a b Kozikowski AP, Nan F, Conti P, Zhang J, Ramadan E, Bzdega T, et al. (February 2001). "Design of remarkably simple, yet potent urea-based inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (NAALADase)". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 44 (3): 298–301. doi:10.1021/jm000406m. PMID 11462970.

- ^ a b c Nagel J, Belozertseva I, Greco S, Kashkin V, Malyshkin A, Jirgensons A, et al. (December 2006). "Effects of NAAG peptidase inhibitor 2-PMPA in model chronic pain - relation to brain concentration". Neuropharmacology. 51 (7–8): 1163–1171. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.018. PMID 16926034. S2CID 21499770.

- ^ Chen SR, Wozniak KM, Slusher BS, Pan HL (February 2002). "Effect of 2-(phosphono-methyl)-pentanedioic acid on allodynia and afferent ectopic discharges in a rat model of neuropathic pain". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 300 (2): 662–667. doi:10.1124/jpet.300.2.662. PMID 11805230. S2CID 8121145.

- ^ Tolias C, Wasserberg J (2002). "Critical decision making in severe head injury management". Trauma. 4 (4): 211–221. doi:10.1191/1460408602ta246oa. S2CID 72178402.

- ^ "What is Stroke". National Stroke Association. Archived from the original on 2006-05-16. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "Schizophrenia". National Mental Health Information Center. Archived from the original on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "Diabetic Neuropathies: The Nerve Damage of Diabetes". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. 2009. Archived from the original on 2005-01-13. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ Berent-Spillson A, Robinson AM, Golovoy D, Slusher B, Rojas C, Russell JW (April 2004). "Protection against glucose-induced neuronal death by NAAG and GCP II inhibition is regulated by mGluR3". Journal of Neurochemistry. 89 (1): 90–99. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2003.02321.x. hdl:2027.42/65724. PMID 15030392. S2CID 7892733.

External links

edit- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: M20.001[permanent dead link]

- Protein Data Bank: Protein Data Bank

- Glutamate+carboxypeptidase+II at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q04609 (Glutamate carboxypeptidase 2) at the PDBe-KB.