Memantine, sold under the brand name Namenda among others, is a medication used to slow the progression of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease.[10][11][8] It is taken by mouth.[10][8]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Axura, Ebixa, Namenda, others[1][2] |

| Other names | 1-Amino-3,5-dimethyladamantane; 3,5-Dimethyladamantan-1-amine; Dimethyladamantanamine; DMAA; D145; D-145 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604006 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | NMDA receptor antagonist |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100%[8][9] |

| Protein binding | 45%[8][9] |

| Metabolism | Minimal[9] |

| Metabolites | • Memantine glucuronide[8][9] • 6-Hydroxymemantine[8][9] • 1-Nitrosomemantine[8][9] |

| Elimination half-life | 60–80 hours[8][9] |

| Excretion | Urine (57–82% unchanged)[8][9] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.217.937 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

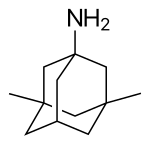

| Formula | C12H21N |

| Molar mass | 179.307 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include headache, constipation, sleepiness, and dizziness.[10][11] Severe side effects may include blood clots, psychosis, and heart failure.[11] It is believed to work by acting on NMDA receptors, working as a pore blocker of these ion channels.[8][10]

Memantine was first discovered in 1963.[8][12][13] It was approved for medical use in Germany in 1989, in the European Union in 2002, and in the United States in 2003.[13][10][14] It is available as a generic medication.[11] In 2022, it was the 150th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[15][16]

Medical uses

editAlzheimer's disease and dementia

editMemantine is used to treat moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease, especially for people who are intolerant of or have a contraindication to AChE (acetylcholinesterase) inhibitors.[17][18] One guideline recommends memantine or an AChE inhibitor be considered in people in the early-to-mid stage of dementia.[19]

Memantine has been associated with a modest improvement;[20] with small positive effects on cognition, mood, behavior, and the ability to perform daily activities in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease.[21][22] There does not appear to be any benefit in mild disease.[23]

Memantine when added to donepezil in those with moderate-to-severe dementia resulted in "limited improvements" in a 2017 review.[24] The UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued guidance in 2018 recommending consideration of the combination of memantine with donepezil in those with moderate-to-severe dementia.[25]

Radiation therapy

editMemantine has been recommended for use by professional organization consensus to prevent neurocognitive decline after whole brain radiotherapy.[26]

Adverse effects

editMemantine is, in general, well tolerated.[20] Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of people) include confusion, dizziness, drowsiness, headache, insomnia, agitation, and/or hallucinations. Less common adverse effects include vomiting, anxiety, hypertonia, cystitis, and increased libido.[20][27]

Like many other NMDA receptor antagonists, memantine behaves as a dissociative anesthetic at supratherapeutic doses.[28] Despite isolated reports, recreational use of memantine is rare due to the drug's long duration and limited availability.[28] Additionally, memantine seems to lack effects such as euphoria or hallucinations.[29]

Memantine appears to be generally well tolerated by children with autism spectrum disorder.[30]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

editGlutamatergic

editA dysfunction of glutamatergic neurotransmission, manifested as neuronal excitotoxicity, is hypothesized to be involved in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease. Targeting the glutamatergic system, specifically ionotropic glutamate NMDA receptors, offers a novel approach to treatment in view of the limited efficacy of existing drugs targeting the cholinergic system.[31]

Memantine is a low-affinity voltage-dependent uncompetitive antagonist at glutamatergic NMDA receptors.[32][33] By binding to the NMDA receptor with a higher affinity than Mg2+ ions, memantine is able to inhibit the prolonged influx of Ca2+ ions, particularly from extrasynaptic receptors, which forms the basis of neuronal excitotoxicity. The low affinity, uncompetitive nature, and rapid off-rate kinetics of memantine at the level of the NMDA receptor channel, however, preserves the function of the receptor at synapses, as it can still be activated by physiological release of glutamate following depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron.[34][35][36] The interaction of memantine with NMDA receptors plays a major role in the symptomatic improvement that the drug produces in Alzheimer's disease. However, there is no evidence as yet that the ability of memantine to protect against extrasynaptic NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity has a disease-modifying effect in Alzheimer's disease, although this has been suggested in animal models.[35]

Serotonergic

editMemantine acts as a non-competitive antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT3 receptor, with a potency similar to that for the NMDA receptor.[37] Many 5-HT3 receptor antagonists function as antiemetics, however the clinical significance of this anti-serotonergic activity of memantine in Alzheimer's disease is unknown.

Cholinergic

editMemantine acts as a non-competitive antagonist of different neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) at potencies possibly similar to the NMDA receptor and 5-HT3 receptor, but this is difficult to ascertain with accuracy because of the rapid desensitization of nAChR responses in these experiments. It can be noted that memantine is an antagonist at α7 nAChR, which may contribute to initial worsening of cognitive function during early memantine treatment. α7 nAChR upregulates quickly in response to antagonism, which could explain the cognitive-enhancing effects of chronic memantine treatment.[38][39] It has been shown that the number of nicotinic receptors in the brain are reduced in Alzheimer's disease, even in the absence of a general decrease in the number of neurons, and nicotinic receptor agonists are viewed as interesting targets for anti-Alzheimer drugs.[40]

Dopaminergic

editMemantine was shown in a study to act as an agonist at the dopamine D2high receptor with equal or slightly higher affinity than to the NMDA receptors.[41] However, the relevance of this action may be negligible, as studies have shown very low affinity for binding to D2 receptors in general.[42]

Sigmaergic

editMemantine acts as an agonist of the sigma σ1 receptor with low affinity (Ki = 2.6 μM).[43] The consequences of this activity are unclear (as the role of sigma receptors in general is currently not very well understood). Due to this low affinity, therapeutic concentrations of memantine are most likely too low to have any sigmaergic effect as a typical therapeutic dose is 20 mg. However, excessive doses of memantine taken for recreational purposes many times greater than prescribed doses may indeed activate this receptor.[44]

Other actions

editMemantine does not appear to inhibit or induce several cytochrome P450 enzymes including CYP3A4/5, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP2C9.[8] It also does not inhibit CYP2A6 or CYP2E1.[9] However, it might have a small effect on CYP2B6.[8]

Pharmacokinetics

editAbsorption

editThe oral bioavailability of memantine is 100%.[8][9] Time to peak levels of memantine is 3 to 7 hours.[8][9] Food has no influence on the rate of absorption.[8][9] Memantine exposure is linear over a dose range of 10 to 40 mg.[8] Peak levels after a single 20 mg dose were found to be 24 to 29 μg/L (0.13–0.16 μmol/L or μM).[8] Steady-state levels of memantine with 20 mg/day are in the range of 0.5 to 1.0 μM.[9]

Distribution

editMemantine has a relatively high volume of distribution (Vd) of 9 to 11 L/kg.[8][9] It easily crosses biological membranes, is widely distributed throughout the body, and crosses the blood–brain barrier into the central nervous system.[9] The drug is transported across the blood–brain barrier by the organic cation transporter novel 1 (OCTN1).[8] The plasma protein binding of memantine is 45% and is described as very low and not clinically significant.[8][9] Because of its low plasma protein binding, it is unlikely to interact with other highly protein-bound drugs such as warfarin or digoxin.[9]

Metabolism

editMemantine does not undergo extensive metabolism.[9] It is negligibly metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzymes.[8][9] As a result, it has a decreased potential for drug interactions.[9] Metabolites of memantine include memantine glucuronide, 6-hydroxymemantine, and 1-nitrosomemantine, all of which show minimal activity as NMDA receptor antagonists.[8][9]

Elimination

editMemantine is eliminated primarily in urine, with 57 to 82% excreted in urine unchanged.[8][9] Its elimination half-life is 60 to 80 hours.[8][9] The renal clearance of memantine is dependent on urinary pH.[8][9] More alkaline urine slows the elimination of memantine, whereas more acidic urine accelerates its elimination.[8][9]

Chemistry

editMemantine, also known as 3,5-dimethyl-1-aminoadamantane (DMAA), is an adamantane derivative and is closely structurally related to amantadine (1-aminoadamantane) and other adamantane derivatives.[8][45][46][47]

History

editMemantine was first synthesized, patented, and described by Eli Lilly and Company in 1963 as an anti-diabetic agent, but it was ineffective at lowering blood sugar.[8][12][13][48][49] By 1972, it was discovered to have central nervous system (CNS) activity, and was developed by Merz for treatment of neurological diseases, such as Parkinson's disease.[8][12] Memantine was first studied in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease in 1986.[13][14] The drug was first marketed for dementia in 1989 in Germany under the name Axura.[8][14][12]

It was not discovered to act as an NMDA receptor antagonist until 1989, after clinical trials had initiated.[8][12][50] Prior to this, it was theorized to directly and/or indirectly modulate the dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic systems.[12][51][52][53] However, these actions were later realized to occur at 100-fold higher concentrations than those achieved therapeutically and hence are unlikely to be involved in its effects.[12][51][53]

In the United States, some CNS activities were discovered at Children's Hospital of Boston in 1990, and Children's licensed patents covering uses of memantine outside the field of ophthalmology to Neurobiological Technologies (NTI) in 1995.[54] In 1998, NTI amended its agreement with Children's to allow Merz to take over development.[55]

In 2000, Merz partnered with Forest to develop the drug for Alzheimer's disease in the United States under the brand name Namenda.[8][14] In 2000, Merz partnered with Suntory for the Japanese market and with Lundbeck for other markets including Europe;[56] the drug was originally marketed by Lundbeck under the name Ebixa.[14] Memantine was approved in the European Union in 2002 and in the United States in 2003.[8][13]

Sales of the drug reached $1.8 billion for 2014.[8][57] The cost of Namenda was $269 to $489 a month in 2012.[58]

In February 2014, as the July 2015 patent expiration for memantine neared, Actavis, which had acquired Forest, announced that it was launching an extended release (XR) form of memantine that could be taken once a day instead of twice a day as needed with the then-current "immediate release" (IR) version, and that it intended to stop selling the IR version in August 2014 and withdraw the marketing authorization. This is a tactic to thwart generic competition called product hopping. However the supply of the XR version ran short, so Actavis extended the deadline until the fall. In September 2014 the attorney general of New York, Eric Schneiderman, filed a lawsuit to compel Actavis to keep selling the IR version on the basis of antitrust law.[59][60]

In December 2014, a judge granted New York State its request and issued an injunction, preventing Actavis from withdrawing the IR version until generic versions could launch. Actavis appealed and in May a panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the injunction, and in June Actavis asked that its case be heard by the full Second Circuit panel.[61][62] In August 2015, Actavis' request was denied.[63]

Society and culture

editRecreational use

editRecreational use of memantine at supratherapeutic doses has been reported.[64] It is a weak NMDA receptor antagonist and is reported to produce dissociative and phencyclidine (PCP)-like effects in animals and humans at sufficiently high doses.[64][65][66] Even therapeutic doses have been found to produce mild dissociative-like effects in clinical studies.[64] In any case, the very long duration of action of memantine (>40 hours) has likely limited its misuse potential.[64] Recreational use of the related drug amantadine has similarly been reported.[64]

A study examining self-reported use of memantine on the social network Reddit showed that the drug was used both recreationally and as a nootropic, but also that it was misused in various illnesses as self-medication without strong scientific basis.[67]

Brand names

editAs of August 2017, memantine is marketed under many brand names worldwide including Abixa, Adaxor, Admed, Akatinol, Alceba, Alios, Almenta, Alois, Alzant, Alzer, Alzia, Alzinex, Alzixa, Alzmenda, Alzmex, Axura, Biomentin, Carrier, Cogito, Cognomem, Conexine, Cordure, Dantex, Demantin, Demax, Dementa, Dementexa, Ebitex, Ebixa, Emantin, Emaxin, Esmirtal, Eutebrol, Evy, Ezemantis, Fentina, Korint, Lemix, Lindex, Lindex, Lucidex, Manotin, Mantine, Mantomed, Marbodin, Mardewel, Marixino, Maruxa, Maxiram, Melanda, Memabix, Memamed, Memando, Memantin, Memantina, Memantine, Mémantine, Memantinol, Memantyn, Memanvitae, Memanxa, Memanzaks, Memary, Memax, Memexa, Memigmin, Memikare, Memogen, Memolan, Memorel, Memorix, Memotec, Memox, Memxa, Mentikline, Mentium, Mentixa, Merandex, Merital, Mexia, Mimetix, Mirvedol, Modualz, Morysa, Namenda, Nemdatine, Nemdatine, Nemedan, Neumantine, Neuro-K, Neuroplus, Noojerone, Polmatine, Prilben, Pronervon, Ravemantine, Talentum, Timantila, Tingreks, Tonibral, Tormoro, Valcoxia, Vilimen, Vivimex, Witgen, Xapimant, Ymana, Zalatine, Zemertinex, Zenmem, Zenmen, and Zimerz.[1]

It is marketed in some countries as a combination drug with donepezil (memantine/donepezil) under the brand names Namzaric, Neuroplus Dual, and Tonibral MD.[1]

Research

editPsychiatric disorders

editMemantine has been studied and used off-label in the treatment of a variety of psychiatric disorders.[68] These include depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), substance misuse, pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs), and binge eating disorder (BED).[68] A 2008 systematic review concluded that although it was promising for such uses, memantine could not be recommended for such indications due to inadequate data.[68]

Memantine does not appear to be effective in the treatment of unipolar major depression or bipolar depression on the basis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, including a 2021 Cochrane review.[69][70][71][72][73] However, a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that memantine was significantly effective in the treatment of depressive symptoms in various psychiatric disorders, although with a very small effect size (Hedges' g = -0.17).[74]

There are likewise limited data to support memantine in the treatment of schizophrenia based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses.[75][76] However, a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis reported that memantine was effective in the treatment of the negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia with medium to large effect sizes.[77]

Parkinson's disease

editMemantine has been studied in the treatment of Parkinson's disease since the early 1970s.[13][12][78][79][80] Whereas the related drug amantadine is approved for the treatment of Parkinson's disease and has been since the early 1970s,[46] memantine is not approved for the treatment of Parkinson's disease as of 2024.[81] However, it has been said that memantine, along with amantadine, has been widely used as an antiparkinsonian agent since at least 1994.[78]

Although amantadine and memantine have fairly similar pharmacology, it has been said that memantine does not share the antidyskinetic effects of amantadine.[82][83] However, findings are conflicting, and some data suggest that memantine may also have antidyskinetic effects.[84][85][86] Similarly to amantadine and dopamine receptor agonists, memantine reverses haloperidol-induced catalepsy and monoamine depletion-induced sedation in animals.[82][87] Memantine has been found to reduce bradykinesia and resting tremor in people with Parkinson's disease.[82][83] Memantine and amantadine are said to have moderate anti-akinetic effects in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[78][88] The doses of memantine used for Parkinson's disease are about 5- to 10-fold lower than those of amantadine, which has been attributed to greater potency of memantine.[78]

As of 2022, a phase 3 clinical trial is studying the potential of memantine as disease-modifying treatment for Parkinson's disease that might slow progression of the disease.[89][90][91] It is specifically theorized to act by inhibiting cell-to-cell transmission of α-synuclein.[89][90]

Besides Parkinson's disease, memantine has been studied in the treatment of Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).[92][93][94]

Apathy

editApathy is a disorder of diminished motivation characterized by diminished interest and activity.[95][96] Systematic reviews and meta-analyses published from 2016 to 2022 have found that memantine is not effective in the treatment of apathy in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.[97][98][99] However, another 2022 review reported that it was effective.[100]

Long COVID

editMemantine, along with amantadine, is being studied and used off-label in the treatment long COVID.[101][102]

Catatonia

editMemantine, along with amantadine, has been reported to be effective in the treatment of catatonia in case reports and case series.[103][104][105]

Autism

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "International brands for memantine". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Schweizerischer Apotheker-Verein (2004). Index Nominum: International Drug Directory. Medpharm Scientific Publishers. p. 753. ISBN 978-3-88763-101-7. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Ebixa 10 mg film-coated tablets Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 13 December 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Namenda- memantine hydrochloride tablet; Namenda- memantine hydrochloride kit". DailyMed. 1 November 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Namenda XR- memantine hydrochloride capsule, extended release; Namenda XR- memantine hydrochloride kit". DailyMed. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Axura EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 May 2002. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Alam S, Lingenfelter KS, Bender AM, Lindsley CW (September 2017). "Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Memantine". ACS Chem Neurosci. 8 (9): 1823–1829. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00270. PMID 28737885.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Schmitt F, Ryan M, Cooper G (February 2007). "A brief review of the pharmacologic and therapeutic aspects of memantine in Alzheimer's disease". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 3 (1): 135–141. doi:10.1517/17425255.3.1.135. PMID 17269900.

- ^ a b c d e "Memantine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 303–304. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h del Río-Sancho S (2020). "Memantine and Alzheimer's disease". Diagnosis and Management in Dementia. Elsevier. pp. 511–527. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815854-8.00032-x. ISBN 978-0-12-815854-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Herrmann N, Li A, Lanctôt K (April 2011). "Memantine in dementia: a review of the current evidence". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 12 (5): 787–800. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.558006. PMID 21385152.

- ^ a b c d e Witt A, Macdonald N, Kirkpatrick P (February 2004). "Memantine hydrochloride". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 3 (2): 109–110. doi:10.1038/nrd1311. PMID 15040575. S2CID 2258982.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Memantine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Mount C, Downton C (July 2006). "Alzheimer disease: progress or profit?". Nature Medicine. 12 (7): 780–784. doi:10.1038/nm0706-780. PMID 16829947. S2CID 31877708.

- ^ NICE review of technology appraisal guidance 111 January 18, 2011 Alzheimer's disease - donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine (review): final appraisal determination Archived 21 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, McLachlan AJ, Etherton-Beer C (October 2016). "Medication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel". Internal Medicine Journal. 46 (10): 1189–1197. doi:10.1111/imj.13215. PMC 5129475. PMID 27527376.

- ^ a b c Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ^ McShane R, Westby MJ, Roberts E, Minakaran N, Schneider L, Farrimond LE, et al. (March 2019). "Memantine for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD003154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub6. PMC 6425228. PMID 30891742.

- ^ van Dyck CH, Tariot PN, Meyers B, Malca Resnick E (2007). "A 24-week randomized, controlled trial of memantine in patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer disease". Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 21 (2): 136–143. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318065c495. PMID 17545739. S2CID 25621202.

- ^ Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JP, McShane R (August 2011). "Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease". Archives of Neurology. 68 (8): 991–998. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.69. PMID 21482915. S2CID 18870666.

- ^ Chen R, Chan PT, Chu H, Lin YC, Chang PC, Chen CY, et al. (21 August 2017). Chen K (ed.). "Treatment effects between monotherapy of donepezil versus combination with memantine for Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 12 (8): e0183586. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1283586C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183586. PMC 5565113. PMID 28827830.

- ^ "Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 20 June 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Vogelbaum MA, Brown PD, Messersmith H, Brastianos PK, Burri S, Cahill D, et al. (February 2022). "Treatment for Brain Metastases: ASCO-SNO-ASTRO Guideline". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 40 (5): 492–516. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.02314. PMID 34932393. S2CID 245385315.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee (2004). British National Formulary (47th ed.). London: BMA and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. ISBN 978-0-85369-584-4.

- ^ a b Morris H, Wallach J (2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 614–632. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ Swedberg MD, Ellgren M, Raboisson P (April 2014). "mGluR5 antagonist-induced psychoactive properties: MTEP drug discrimination, a pharmacologically selective non-NMDA effect with apparent lack of reinforcing properties". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 349 (1): 155–164. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.211185. PMID 24472725. S2CID 787751.

- ^ Elbe D (2019). Clinical handbook of psychotropic drugs for children and adolescents (Tertiary source). Boston, MA: Hogrefe. pp. 366–369. ISBN 978-1-61676-550-7. OCLC 1063705924.

- ^ Cacabelos R, Takeda M, Winblad B (January 1999). "The glutamatergic system and neurodegeneration in dementia: preventive strategies in Alzheimer's disease". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14 (1): 3–47. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199901)14:1<3::AID-GPS897>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 10029935. S2CID 12141540.

- ^ Rogawski MA, Wenk GL (2003). "The neuropharmacological basis for the use of memantine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease". CNS Drug Reviews. 9 (3): 275–308. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2003.tb00254.x. PMC 6741669. PMID 14530799.

- ^ Robinson DM, Keating GM (2006). "Memantine: a review of its use in Alzheimer's disease". Drugs. 66 (11): 1515–1534. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666110-00015. PMID 16906789. S2CID 212617566.

- ^ Xia P, Chen HS, Zhang D, Lipton SA (August 2010). "Memantine preferentially blocks extrasynaptic over synaptic NMDA receptor currents in hippocampal autapses". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (33): 11246–11250. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-10.2010. PMC 2932667. PMID 20720132.

- ^ a b Parsons CG, Stöffler A, Danysz W (November 2007). "Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system--too little activation is bad, too much is even worse". Neuropharmacology. 53 (6): 699–723. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.013. PMID 17904591. S2CID 6599658.

- ^ Lipton SA (October 2007). "Pathologically activated therapeutics for neuroprotection". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (10): 803–808. doi:10.1038/nrn2229. PMID 17882256. S2CID 34931289.

- ^ Rammes G, Rupprecht R, Ferrari U, Zieglgänsberger W, Parsons CG (June 2001). "The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel blockers memantine, MRZ 2/579 and other amino-alkyl-cyclohexanes antagonise 5-HT(3) receptor currents in cultured HEK-293 and N1E-115 cell systems in a non-competitive manner". Neuroscience Letters. 306 (1–2): 81–84. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)01872-9. PMID 11403963. S2CID 9655208.

- ^ Buisson B, Bertrand D (March 1998). "Open-channel blockers at the human alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 53 (3): 555–563. doi:10.1124/mol.53.3.555. PMID 9495824. S2CID 5865674.

- ^ Aracava Y, Pereira EF, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX (March 2005). "Memantine blocks alpha7* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors more potently than n-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in rat hippocampal neurons". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 312 (3): 1195–1205. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.077172. PMID 15522999. S2CID 17585264.

- ^ Gotti C, Clementi F (December 2004). "Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology". Progress in Neurobiology. 74 (6): 363–396. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.006. PMID 15649582. S2CID 24093369.

- ^ Seeman P, Caruso C, Lasaga M (February 2008). "Memantine agonist action at dopamine D2High receptors". Synapse. 62 (2): 149–153. doi:10.1002/syn.20472. hdl:11336/108388. PMID 18000814. S2CID 20494427.

- ^ "Memantine Ki values". PDSP Ki Database. UNC. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Peeters M, Romieu P, Maurice T, Su TP, Maloteaux JM, Hermans E (April 2004). "Involvement of the sigma 1 receptor in the modulation of dopaminergic transmission by amantadine". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (8): 2212–2220. doi:10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03297.x. PMID 15090047. S2CID 19479968.

- ^ "Pharms - Memantine (also Namenda) : Erowid Exp: Main Index". erowid.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Ragshaniya A, Kumar V, Tittal RK, Lal K (March 2024). "Nascent pharmacological advancement in adamantane derivatives". Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 357 (3): e2300595. doi:10.1002/ardp.202300595. PMID 38128028.

- ^ a b Danysz W, Dekundy A, Scheschonka A, Riederer P (February 2021). "Amantadine: reappraisal of the timeless diamond-target updates and novel therapeutic potentials". J Neural Transm (Vienna). 128 (2): 127–169. doi:10.1007/s00702-021-02306-2. PMC 7901515. PMID 33624170.

- ^ Morozov IS, Ivanova IA, Lukicheva TA (2001). "[Actoprotector and adaptogen properties of adamantane derivatives (a review)". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 35 (5): 235–238. doi:10.1023/A:1011905302667.

- ^ Gerzon K, Krumkalns EV, Brindle RL, Marshall FJ, Root MA (November 1963). "The adamantyl group in medicinal agents. I. Hypoglycemic N-arylsulfonyl-N'-adamantylureas". J Med Chem. 6 (6): 760–763. doi:10.1021/jm00342a029. PMID 14184942.

- ^ Elks J (2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer US. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Bormann J (August 1989). "Memantine is a potent blocker of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channels". Eur J Pharmacol. 166 (3): 591–592. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90385-3. PMID 2553441.

- ^ a b Parsons CG, Danysz W, Quack G (June 1999). "Memantine is a clinically well tolerated N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist--a review of preclinical data". Neuropharmacology. 38 (6): 735–767. doi:10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00019-2. PMID 10465680.

- ^ Wesemann W, Sontag KH, Maj J (1983). "Pharmakodynamik und Pharmakokinetik des Memantin" [Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of memantine]. Arzneimittelforschung (in German). 33 (8): 1122–1134. PMID 6357202.

- ^ a b Jackisch R, Link T, Neufang B, Koch R (1992). "Studies on the mechanism of action of the antiparkinsonian drugs memantine and amantadine: no evidence for direct dopaminomimetic or antimuscarinic properties". Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 320: 21–42. PMID 1284458.

- ^ "Form 10-KSB For the fiscal year ended June 30, 1996". SEC Edgar. 30 September 1996. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017. NTI-Children's license is included in the filing.

- ^ Delevett P (9 January 2000). "Cash is king, focus is queen". Silicon Valley Business Journal. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ Staff (15 August 2000). "Lundbeck signs memantine licensing agreement for Merz+Co". The Pharma Letter. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Namenda Sales Data". Drugs.com. February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Evaluating Prescription Drugs Used to Treat: Alzheimer's Disease. Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF). Consumer Reports Health. May 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Pollack A (15 September 2014). "Forest Laboratories' Namenda Is Focus of Lawsuit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Capati VC, Kesselheim AS (April 2016). "Drug Product Life-Cycle Management as Anticompetitive Behavior: The Case of Memantine". Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 22 (4): 339–344. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.4.339. PMC 10398055. PMID 27023687.

- ^ "Actavis Confirms Appeals Court Ruling Requiring Continued Distribution of Namenda IR". Actavis. 22 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Gurrieri V (9 June 2015). "Actavis, Others Plotted To Delay Generic Namenda, Suit Says". Law360. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ LoBiondo GA (12 August 2015). "Second Circuit Denies Petition for Actavis Rehearing | David Kleban". Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Morris H, Wallach J (2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Test Anal. 6 (7–8): 614–632. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ Heal DJ, Gosden J, Smith SL (November 2018). "Evaluating the abuse potential of psychedelic drugs as part of the safety pharmacology assessment for medical use in humans". Neuropharmacology. 142: 89–115. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.049. PMID 29427652.

- ^ Nicholson KL, Jones HE, Balster RL (May 1998). "Evaluation of the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus properties of the low-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate channel blocker memantine". Behavioural Pharmacology. 9 (3): 231–243. PMID 9832937. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Natter J, Michel B (September 2020). "Memantine misuse and social networks: A content analysis of Internet self-reports". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 29 (9): 1189–1193. doi:10.1002/pds.5070. PMID 32602152. S2CID 220270495.

- ^ a b c Zdanys K, Tampi RR (August 2008). "A systematic review of off-label uses of memantine for psychiatric disorders". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 32 (6): 1362–1374. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.01.008. PMID 18262702.

- ^ Dean RL, Hurducas C, Hawton K, Spyridi S, Cowen PJ, Hollingsworth S, et al. (September 2021). "Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults with unipolar major depressive disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9 (9): CD011612. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub3. PMC 8434915. PMID 34510411.

- ^ Kleeblatt J, Betzler F, Kilarski LL, Bschor T, Köhler S (May 2017). "Efficacy of off-label augmentation in unipolar depression: A systematic review of the evidence". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 27 (5): 423–441. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.03.003. PMID 28318897.

- ^ Kishi T, Matsunaga S, Iwata N (2017). "A Meta-Analysis of Memantine for Depression". J Alzheimers Dis. 57 (1): 113–121. doi:10.3233/JAD-161251. PMID 28222534.

- ^ Veronese N, Solmi M, Luchini C, Lu RB, Stubbs B, Zaninotto L, et al. (June 2016). "Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the efficacy and safety for multiple disease dimensions". J Affect Disord. 197: 268–280. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.034. PMID 27010579.

- ^ Bartoli F, Cavaleri D, Bachi B, Moretti F, Riboldi I, Crocamo C, et al. (November 2021). "Repurposed drugs as adjunctive treatments for mania and bipolar depression: A meta-review and critical appraisal of meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 143: 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.018. PMID 34509090. S2CID 237485915.

- ^ Hsu TW, Chu CS, Ching PY, Chen GW, Pan CC (June 2022). "The efficacy and tolerability of memantine for depressive symptoms in major mental diseases: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials". J Affect Disord. 306: 182–189. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.047. PMID 35331821.

- ^ Andrade C (2017). "Memantine as an Augmentation Treatment for Schizophrenia: Limitations of Meta-Analysis for Evidence-Based Evaluation of Research". J Clin Psychiatry. 78 (9): e1307–e1309. doi:10.4088/JCP.17f11998. PMID 29178686.

- ^ Kishi T, Ikuta T, Oya K, Matsunaga S, Matsuda Y, Iwata N (August 2018). "Anti-Dementia Drugs for Psychopathology and Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 (8): 748–757. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyy045. PMC 6070030. PMID 29762677.

- ^ Zheng W, Zhu XM, Zhang QE, Cai DB, Yang XH, Zhou YL, et al. (July 2019). "Adjunctive memantine for major mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled trials". Schizophr Res. 209: 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.05.019. PMID 31164254.

- ^ a b c d Lange KW, Riederer P (1994). "Glutamatergic drugs in Parkinson's disease" (PDF). Life Sci. 55 (25–26): 2067–2075. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(94)00387-4. PMID 7997066.

- ^ Fischer PA, Jacobi P, Schneider E, Schönberger B (July 1977). "Die Wirkung intravenöser Gaben von Memantin bei Parkinson-Kranken" [Effects of intravenous administration of memantine in parkinsonian patients]. Arzneimittelforschung (in German). 27 (7): 1487–1489. PMID 332193.

- ^ Schneider E, Fischer PA, Clemens R, Balzereit F, Fünfgeld EW, Haase HJ (June 1984). "[Effects of oral memantine administration on Parkinson symptoms. Results of a placebo-controlled multicenter study]". Dtsch Med Wochenschr (in German). 109 (25): 987–990. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1069311. PMID 6734455.

- ^ "Memantine - Children's Medical Center Corporation/Merz Pharma". AdisInsight. 5 November 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ a b c Olivares D, Deshpande VK, Shi Y, Lahiri DK, Greig NH, Rogers JT, et al. (July 2012). "N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists and memantine treatment for Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and Parkinson's disease". Curr Alzheimer Res. 9 (6): 746–758. doi:10.2174/156720512801322564. PMC 5002349. PMID 21875407.

- ^ a b Merello M, Nouzeilles MI, Cammarota A, Leiguarda R (1999). "Effect of memantine (NMDA antagonist) on Parkinson's disease: a double-blind crossover randomized study". Clin Neuropharmacol. 22 (5): 273–276. PMID 10516877.

- ^ Gonzalez-Latapi P, Bhowmick SS, Saranza G, Fox SH (October 2020). "Non-Dopaminergic Treatments for Motor Control in Parkinson's Disease: An Update". CNS Drugs. 34 (10): 1025–1044. doi:10.1007/s40263-020-00754-0. PMID 32785890.

- ^ Onofrj M, Frazzini V, Bonanni L, Thomas A (2016). "Chapter 3 - Amantadine and antiglutamatergic drugs in the management of Parkinson's disease". In Gálvez-Jiménez N, Fernandez HH, Espay AJ, Fox SH (eds.). Parkinson's Disease: Current and Future Therapeutics and Clinical Trials. Cambridge medicine. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-107-05386-1. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Vidal EI, Fukushima FB, Valle AP, Villas Boas PJ (January 2013). "Unexpected improvement in levodopa-induced dyskinesia and on-off phenomena after introduction of memantine for treatment of Parkinson's disease dementia". J Am Geriatr Soc. 61 (1): 170–172. doi:10.1111/jgs.12058. PMID 23311565.

- ^ Danysz W, Gossel M, Zajaczkowski W, Dill D, Quack G (1994). "Are NMDA antagonistic properties relevant for antiparkinsonian-like activity in rats?--case of amantadine and memantine". J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 7 (3): 155–166. doi:10.1007/BF02253435. PMID 7710668.

- ^ Rabey JM, Nissipeanu P, Korczyn AD (1992). "Efficacy of memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, in the treatment of Parkinson's disease". J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 4 (4): 277–282. doi:10.1007/BF02260076. PMID 1388698.

- ^ a b Grosso Jasutkar H, Oh SE, Mouradian MM (January 2022). "Therapeutics in the Pipeline Targeting α-Synuclein for Parkinson's Disease". Pharmacol Rev. 74 (1): 207–237. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.120.000133. PMC 11034868. PMID 35017177.

- ^ a b McFarthing K, Rafaloff G, Baptista M, Mursaleen L, Fuest R, Wyse RK, et al. (2022). "Parkinson's Disease Drug Therapies in the Clinical Trial Pipeline: 2022 Update". Journal of Parkinson's Disease. 12 (4): 1073–1082. doi:10.3233/JPD-229002. PMC 9198738. PMID 35527571.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT03858270 for "Inhibition of α-synuclein Cell-cell Transmission by NMDAR Blocker, Memantine" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Ballard C, Kahn Z, Corbett A (October 2011). "Treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia". Drugs Aging. 28 (10): 769–777. doi:10.2165/11594110-000000000-00000. PMID 21970305.

- ^ Szeto JY, Lewis SJ (2016). "Current Treatment Options for Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease Dementia". Curr Neuropharmacol. 14 (4): 326–338. doi:10.2174/1570159x14666151208112754. PMC 4876589. PMID 26644155.

- ^ Wang HF, Yu JT, Tang SW, Jiang T, Tan CC, Meng XF, et al. (February 2015). "Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's disease dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 86 (2): 135–143. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-307659. PMID 24828899.

- ^ Marin RS, Wilkosz PA (2005). "Disorders of diminished motivation". J Head Trauma Rehabil. 20 (4): 377–388. doi:10.1097/00001199-200507000-00009. PMID 16030444.

- ^ Chong TT, Husain M (2016). "The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology and treatment of apathy". Motivation - Theory, Neurobiology and Applications. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 229. pp. 389–426. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2016.05.007. ISBN 978-0-444-63701-7. PMID 27926449.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Sepehry AA, Sarai M, Hsiung GR (May 2017). "Pharmacological Therapy for Apathy in Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Can J Neurol Sci. 44 (3): 267–275. doi:10.1017/cjn.2016.426. PMID 28148339.

- ^ Harrison F, Aerts L, Brodaty H (November 2016). "Apathy in Dementia: Systematic Review of Recent Evidence on Pharmacological Treatments". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 18 (11): 103. doi:10.1007/s11920-016-0737-7. PMID 27726067.

- ^ Andrade C (February 2022). "Methylphenidate and Other Pharmacologic Treatments for Apathy in Alzheimer's Disease". J Clin Psychiatry. 83 (1). doi:10.4088/JCP.22f14398. PMID 35120284.

- ^ Azhar L, Kusumo RW, Marotta G, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N (February 2022). "Pharmacological Management of Apathy in Dementia". CNS Drugs. 36 (2): 143–165. doi:10.1007/s40263-021-00883-0. PMID 35006557.

- ^ Müller T, Riederer P, Kuhn W (February 2023). "Aminoadamantanes: from treatment of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease to symptom amelioration of long COVID-19 syndrome?". Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 16 (2): 101–107. doi:10.1080/17512433.2023.2176301. PMID 36726198.

- ^ Frontera JA, Guekht A, Allegri RF, Ashraf M, Baykan B, Crivelli L, et al. (November 2023). "Evaluation and treatment approaches for neurological post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: A consensus statement and scoping review from the global COVID-19 neuro research coalition". J Neurol Sci. 454: 120827. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2023.120827. PMID 37856998.

- ^ Beach SR, Gomez-Bernal F, Huffman JC, Fricchione GL (September 2017). "Alternative treatment strategies for catatonia: A systematic review". Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 48: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.06.011. PMID 28917389.

- ^ Obregon DF, Velasco RM, Wuerz TP, Catalano MC, Catalano G, Kahn D (July 2011). "Memantine and catatonia: a case report and literature review". J Psychiatr Pract. 17 (4): 292–299. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000400268.60537.5e. PMID 21775832.

- ^ Graziane J, Davidowicz E, Francis A (2020). "Can Memantine Improve Catatonia and Co-occurring Cognitive Dysfunction? A Case Report and Brief Literature Review". Psychosomatics. 61 (6): 759–763. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.026. PMID 32665151.

- ^ Parr J (January 2010). "Autism". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2010. PMC 2907623. PMID 21729335.

- ^ Hong MP, Erickson CA (August 2019). "Investigational drugs in early-stage clinical trials for autism spectrum disorder". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 28 (8). Informa UK Limited: 709–718. doi:10.1080/13543784.2019.1649656. PMID 31352835. S2CID 198967266.

Further reading

edit- Lipton SA (April 2005). "The molecular basis of memantine action in Alzheimer's disease and other neurologic disorders: low-affinity, uncompetitive antagonism". Current Alzheimer Research. 2 (2): 155–165. doi:10.2174/1567205053585846. PMID 15974913.