You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

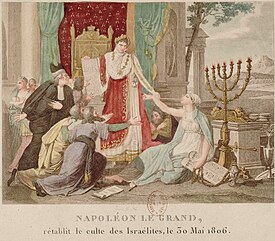

The first laws to emancipate Jews in France were enacted during the French Revolution, establishing them as citizens equal to other Frenchmen. In countries that Napoleon Bonaparte's ensuing Consulate and French Empire conquered during the Napoleonic Wars, he emancipated the Jews and introduced other ideas of liberty. He overrode old laws restricting Jews to reside in ghettos, removed the forced identification of Jews by their wearing the Star of David. In Malta, he ended the enslavement of Jews and permitted the construction of a synagogue there. He also lifted laws that limited Jews' rights to property, worship, and certain occupations.[1] In anticipation of a victory in the Holy Land that failed to come about, he wrote a proclamation published in April 1799 for a Jewish homeland there.[2]

In an effort to promote Jewish integration into French society, however, Napoleon also implemented several policies that eroded Jewish separateness. He restricted the practice of Jews lending money, in the Decree on Jews and Usury (1806), restricted the regions to which Jews were allowed to migrate, and required Jews to adopt formal names. He also implemented a series of consistories, which served as an effective channel utilised by the French government to regulate Jewish religious life.

Historians have disagreed about Napoleon's intentions in these actions, as well as his personal and political feelings about the Jewish community. Some[who?] have said he had political reasons but did not have sympathy for the Jews. His actions were generally opposed by the leaders of monarchies in other countries. After his defeat by the Coalition against France, a counter-revolution swept many of these countries and restored discriminatory measures against the Jews.

Napoleon's laws and the Jews

editThe French Revolution abolished religious persecution that had existed under the monarchy. The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen guaranteed freedom of religion and free exercise of worship, provided that it did not contradict public order. At that time, most other European countries implemented measures of religious persecution towards religious minorities. Many Catholic countries were intolerant and had established religious Inquisitions, sanctioning Jews and Protestants. In the tolerant Protestant-ruled Dutch Republic, Jews and Catholics did not have equal rights until it came under French dominance.

In the early 19th century, through his conquests in Europe, Napoleon spread the modernist liberal ideas of revolutionary France: equality before the law and the rule of law. Napoleon's attitudes towards the Jews have been interpreted in various ways by historians. He made statements both in support of and in opposition to Jews as a group and had that changed. In 1990, Orthodox Rabbi Berel Wein claimed that Napoleon was interested primarily in seeing the Jews assimilate, rather than prosper as a distinct community: "Napoleon's outward tolerance and fairness toward Jews was actually based upon his grand plan to have them disappear entirely by means of total assimilation, intermarriage, and conversion."[3]

Napoleon was concerned about the role of Jews as moneylenders, wanting to end that. The treatment of the Alsace Jews and their debtors was raised in the Imperial Council on 30 April 1806.[citation needed] His liberation of the Jewish communities in Italy (notably in Ancona in the Papal States) and his insistence on the integration of Jews as equals in French and Italian societies demonstrates that he distinguished between usurers (whether Jewish or not), whom he compared to locusts, and those Jews who accepted non-Jews as their equals.

In a letter to Jean-Baptiste Nompère de Champagny, Minister of the Interior on 29 November 1806, Napoleon wrote:

- [It is necessary to] reduce, if not destroy, the tendency of Jewish people to practice a very great number of activities that are harmful to civilisation and to public order in society in all the countries of the world. It is necessary to stop the harm by preventing it; to prevent it, it is necessary to change the Jews. [...] Once part of their youth will take its place in our armies, they will cease to have Jewish interests and sentiments; their interests and sentiments will be French.[4]

While insisting on the primacy of civil law over the military, Napoleon retained a deep respect and affection for the military as a profession. He often hired former soldiers in civilian occupations. Some French Jews served in the military.

Through his policies overall, Napoleon greatly improved the condition of the Jews in France and Europe. Starting in 1806, Napoleon passed a number of measures enhancing the position of the Jews in the French Empire[citation needed]. He accepted a representative group elected by the Jewish community, the Grand Sanhedrin, as their representatives to the French government.

In conquered countries, he abolished laws restricting Jews to living in ghettos. In 1807, he designated Judaism as one of the official religions of France, along with Roman Catholicism (long the established state religion), Lutheran and Calvinist Protestantism (Huguenots, followers of the latter, had been severely persecuted by the monarchy in the late 17th and 18th centuries)[citation needed].

In 1808 Napoleon rolled back a number of reforms (under the so-called décret infâme, or Infamous Decree, of 17 March 1808), declaring all debts with Jews to be annulled, reduced or postponed. The Infamous Decree imposed a ten-year ban on any kind of Jewish money-lending activity. Similarly, Jews who were in subservient positions—such as a Jewish servant, military officer, or wife—were unable to engage in any kind of money-lending activity without the explicit consent of their superiors. Napoleon's goal in implementing the Infamous Decree of 1808 was to integrate Jewish culture and customs into those of France. By restricting money-lending activity, Jews would be forced to engage in other practices for a living. Likewise, in order to even engage in money-lending activity, the decree required Jews to apply for an annual license, granted only with the recommendation of the Jews' local consistory and with the surety of the Jews' honesty.[5] This caused so much financial loss that the Jewish community nearly collapsed.

On a different note, the Infamous Decree also placed heavy restrictions on the Jews' ability to migrate. The decree prevented the Jews from relocating to the regions of Alsace and required that Jews wishing to move to other regions of France to own or purchase land to farm. It also required them to refrain from engaging in any kind of money-lending activity (the law eventually placed these restrictions only on the Jews of the northeast). Likewise, the decree required Jews to serve in the French military, without any opportunity to provide a replacement.[5]

The last component of the Infamous Decree – established in July 1808 – required Jews to adopt formal names with which they would be addressed (before, Jews were often referred to as "Joseph son of Benjamin"). They were also prevented from selecting names of cities or names in the Hebrew Bible. Napoleon sought to integrate the Jewish people more fully into French society by establishing the guidelines they were required to follow in adopting names.[5] Napoleon ended these restrictions by 1811.

Historian Ben Weider argued that Napoleon had to be extremely careful in defending oppressed minorities such as Jews, because of keeping balance with other political interests, but says that the leader clearly saw the political benefit to his Empire in the long term in supporting them. Napoleon hoped to use equality as a way of gaining advantage from discriminated groups, like Jews or Protestants.

Both aspects of his thinking can be seen in an 1818 response to physician Barry O'Meara, his physician during his exile on St. Helena, asking why he pressed for the emancipation of the Jews:

- I wanted to make them leave off usury, and become like other men... by putting them upon an equality, with Catholics, Protestants, and others, I hoped to make them become good citizens, and conduct themselves like others of the community... as their rabbins explained to them, that they ought not to practise usury to their own tribes, but were allowed to do so with Christians and others, that, therefore, as I had restored them to all their privileges... they were not permitted to practise usury with me or them, but to treat us as if we were of the tribe of Judah. Besides, I should have drawn great wealth to France as the Jews are very numerous, and would have flocked to a country where they enjoyed such superior privities. Moreover, I wanted to establish an universal liberty of conscience.[6]

However, in a private letter to his brother Jérôme, dated 6 March 1808, Napoleon wrote the following:

- I have undertaken to reform the Jews, but I have not endeavoured to draw more of them into my realm. Far from that, I have avoided doing anything which could show any esteem for the most despicable of mankind.[7][non-primary source needed]

Napoleon's proclamation to the Jews of Africa and Asia

editDuring Napoleon's siege of Acre in 1799, Gazette Nationale, the main French newspaper during the French Revolution, published on 3 Prairial, (French Republican Calendar Year 7, equivalent to 22 May 1799) a short statement that:

"Bonaparte has published a proclamation in which he invites all the Jews of Asia and Africa to gather under his flag in order to re-establish the ancient Jerusalem. He has already given arms to a great number, and their battalions threaten Aleppo."[8]

The French campaign in Egypt and Syria was eventually defeated by a combined Anglo-Ottoman force and he never carried out his alleged plan. Historian Nathan Schur in Napoleon and the Holy Land (2006) believes that Napoleon intended the proclamation for propaganda and to build support for his campaign among the Jews in those regions. Ronald Schechter believes that the newspaper was reporting a rumour, as there is no documentation that Napoleon contemplated such a policy.[9] The proclamation might have been intended to gain support from Haim Farhi, the Jewish advisor to Ahmed al Jazzar, the Muslim ruler of Acre, and to bring him over to Napoleon's side. Farhi commanded the defence of Acre on the field.[citation needed]

The idea itself may have originated from Thomas Corbet (1773–1804), an Anglo-Irish Protestant emigree who, as a member of the Society of United Irishmen, was an ally of the Republican regime, engaged in revolutionary activities against the Dublin Castle administration and served in the French Army.[10][11] His brother, William Corbet also served as a general in the French Army. In February 1799, he authored a letter to the French Directory, then under the leadership of Napoleon's patron Paul Barras.[10] In the letter he stated "I recommend you, Napoleon, to call on the Jewish people to join your conquest in the East, to your mission to conquer the land of Israel" saying, "Their riches do not console them for their hardships. They await with impatience the epoch of their re-establishment as a nation."[11] Dr. Milka Levy-Rubin, a curator at the National Library of Israel, has attributed Corbert's motivation to a Protestant Zionism based on premillennialist themes.[10] It is not known what Napoleon's direct response was to the letter, but he made his own proclamation three months later.

In 1940, historian Franz Kobler claimed to have found a detailed version of the proclamation from a German translation.[12] Kobler's claim was published in The New Judaea, the official periodical of the World Zionist Organization.[13] The Kobler version suggests that Napoleon was inviting Jews across the Mideast and North Africa to create a Jewish homeland.[14] It includes phrases such as "Rightful heirs of Palestine!" and "your political existence as a nation among the nations." These concepts have been more commonly associated with the Zionist movement, which developed in the late 19th century.[14]

Historians such as Henry Laurens, Ronald Schechter, and Jeremy Popkin believe that the German document, which has never been found, was a forgery, as Simon Schwarzfuchs asserted in his 1979 book.[15][16][17][18][19]

Rabbi Aharon Ben-Levi of Jerusalem also added his voice to the proclamation, calling on the Jews to enlist in Napoleon's army "to return to Zion as in the days of Ezra and Nehemiah" and rebuild the Temple. According to Mordechai Gichon, a military historian and archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, who summarised 40 years of research on the subject, Napoleon had an idea to establish a national home for the Jews in the Land of Israel, "Napoleon believed the Jews would repay his favours by serving French interests in the region," Gichon claimed. "After returning to France, all he was interested in when it came to the Jews was how to use them to reinforce the French nation," Gichon says. "Therefore, he tried to conceal the Zionist chapter of his past." On the other hand, Ze'ev Sternhell believes the entire story is nothing more than an oddity. "Napoleon's big contribution came, in fact, in form of promoting the incorporation of the Jews into French society."[20]

Reactions by major European powers

editRussian Emperor Alexander I objected to Napoleon's emancipation of the Jews and establishment of the Grand Sanhedrin. He vehemently denounced the liberties given to Jews and demanded that the Russian Orthodox Church protest against Napoleon's tolerant religious policy. He referred to the emperor in a proclamation as "the Anti-Christ" and the "Enemy of God". The Holy Synod of Moscow proclaimed: "In order to destroy the foundations of the Churches of Christendom, the Emperor of the French has invited into his capital all the Judaic synagogues and he furthermore intends to found a new Hebrew Sanhedrin ― the same council that the Christian Bible states, condemned to death (by crucifixion) the revered figure, Jesus of Nazareth."[citation needed] Alexander persuaded Napoleon to sign a 17 March 1808 decree restricting the freedoms accorded to the Jews. Napoleon expected in exchange that the tsar would help persuade the British to seek peace with France. Absent that, three months later, Napoleon effectively cancelled the decree by allowing local authorities to implement his earlier reforms. More than half of the French departments restored citizens' guaranteed freedoms to the Jews.[citation needed]

In Austria, Chancellor Klemens von Metternich wrote, "I fear that the Jews will believe (Napoleon) to be their promised Messiah".[citation needed]

In Prussia, leaders of the Lutheran Church were extremely hostile to Napoleon's actions. Italian kingdoms were suspicious of his actions, although expressing less violent opposition. [citation needed]

The British government, which was at war with Napoleon, rejected the principle and doctrine of the Sanhedrin. Lionel Rothschild was elected as a Member of Parliament three times before he could take his seat in Parliament in 1858.[21]

Napoleon's legacy

editNapoleon had more influence on the Jews in Europe than detailed in his decrees. By breaking up the feudal castes of mid-Europe and introducing the equality of the French Revolution, he achieved more for Jewish emancipation than had been accomplished during the three preceding centuries. As part of recognising the Jewish community, he established a national Israelite Consistory in France. It was intended to serve as a centralising authority for Jewish religious and community life. Napoleon implemented several other regional consistories throughout the French Empire, as well, with the Israelite Consistory serving as the lead consistory; it had the responsibility of overseeing the various regional consistories. The regional consistories, in turn, oversaw the economic and religious aspects of Jewish life. The regional consistories consisted of a five-individual board, usually occupied by one (or in some cases two) rabbi, and the rest lay individuals who lived in the districts over which the consistory maintained jurisdiction. The Israelite Consistory in France consisted of three rabbis and two lay individuals. In charge of the Israelite Consistory (and the consistory system in general) was a 25-member board. The members of the board, all Jews, were appointed by the prefect, thus allowing the French government to regulate the system of consistories and, in turn, various aspects of Jewish life.[5] Similarly he established the Royal Westphalian Consistory of the Israelites. This served as a model for other German states until after the fall of Napoleon. Napoleon permanently improved the condition of the Jews in the Prussian Rhine provinces by his rule of this area.

Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Börne both recorded their sense of obligation to Napoleon's principles of action.[22] German Jews in particular have historically regarded Napoleon as the major forerunner of Jewish emancipation in Germany. When the government required Jews to select surnames according to the mainstream model, some are said to have taken the name of Schöntheil, a translation of "Bonaparte."[22] In the Jewish ghettos, legends about Napoleon's actions emerged.[22] Twentieth-century Italian author Primo Levi wrote that Italian Jews often chose Napoleone and Bonaparte as their given name to recognise their historic liberator.[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon: A Life. New York: Penguin Books 2015, 403

- ^ Darwish, Mahmoud Ahmed, and Huda Abdel Rahim Abdel Kadir. "Napoleon Bonaparte's Declaration for the Estbalishment for of the National Home for the Jews in Palestine". International Journal of Cultural Inheritance & Social Sciences ISSN: 2632-7597 3.6 (2021): 1-30.

- ^ Wein, Berel (1990). Triumph of Survival: The Story of the Jews in the Modern Era, 1650-1990. Jewish history, a trilogy, 3. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Shaar Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4226-1514-0. OCLC 933777867.

- ^ Napoleon’s Attempt to Destroy the Jews Retrieved 19 May 2024

- ^ a b c d Hyman, Paula (1998). The Jews of modern France. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520919297. OCLC 44955842.

- ^ O'Meara, Barry Edward (1822). "Napoleon in Exile". Internet Archive. London. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Napoleon, I (1898). "New letters of Napoleon I". Internet Archive. London, W. Heinemann. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Weider, Ben (1997). "Napoléon et les Juifs" (PDF). Congrès de la Société Internationale Napoléonienne, Alexandrie, Italie; 21-26 Juin 1997 (in French). Napoleonic Society. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

Bonaparte, Commandant en chef des Armées de la République Française en Afrique et en Asie, aux héritiers légitimes de la Palestin

- ^ Schechter, Ronald (2003). Obstinate Hebrews: Representations of Jews in France, 1715–1815. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520235571.

- ^ a b c "New exhibition shows letter advising Jewish state in Israel". Ynet News. 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b "The perils of religious mysticism". Irish Democrat. 29 December 2002.

- ^ Kobler, Franz (1940). Napoleon and the restoration of the Jews to Palestine. The New Judaea.

- ^ "The Menorah Journal". Intercollegiate Menorah Association. 37. New York: 388. 1949.

- ^ a b Schwarzfuchs, Simon (1979). "Napoleon, the Jews and the Sanhedrin". Routledge.

- ^ Schwarzfuchs, Simon (1979). Napoleon, the Jews and the Sanhedrin. Routledge. pp. 24–26.

- ^ Laurens, Henry, Orientales I, Autour de l'expédition d'Égypte, pp.123–143, CNRS Éd (2004), ISBN 2-271-06193-8

- ^ Schechter, Ronald (14 April 2003). Obstinate Hebrews: Representations of Jews in France, 1715-1815. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92935-7.

- ^ Mufti, Aamir R. (10 January 2009). Enlightenment in the Colony. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400827664.

- ^ Jeremy D. Popkin (1981). "Zionism and the Enlightenment: The "Letter of a Jew to His Brethren"". Jewish Social Studies. 43: 113–120.

The supposed German manuscript original has never surfaced, and the authenticity of this text is dubious at best. ... The French press of the period is full of spurious flews reports...

- ^ "Herzl Hinted at Napoleon's Zionist Past'". Haaretz Daily Newspaper. April 2004.

- ^ Roberts, Napoleon: A Life, p. 403

- ^ a b c Jacobs, Joseph. "NAPOLEON BONAPARTE". JewishEncyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

Further reading

edit- Berkovitz, Jay R. "The Napoleonic Sanhedrin: Halachic Foundations and Rabbinical Legacy." CCAR JOURNAL 54.1 (2007): 11.

- Brenner, Michael, Vicki Caron, and Uri R. Kaufman, eds.Jewish Emancipation Reconsidered 2003.

- Cooper, Levi. "Napoleonic freedom of worship in law and art." Journal of Law and Religion 34.1 (2019): 3-41.

- Darwish, Mahmoud Ahmed, and Huda Abdel Rahim Abdel Kadir. "Napoleon Bonaparte's Declaration for the Establishment for of the National Home for the Jews in Palestine". International Journal of Cultural Inheritance & Social Sciences ISSN: 2632-7597 3.6 (2021): 1-30.

- Goodman, Mark. "Napoleon, the Tzars, and the Emancipation of Jewry in Continental Europe". International Journal of Russian Studies 10.2 (2021).

- Kohn, Hans. "Napoleon and the Age of Nationalism." The Journal of Modern History 22.1 (1950): 21-37.

- Newman, Aubrey. "Napoleon and the Jews." European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe 2.2 (1967): 25-32.

- Renard, Nils. "Being a Jewish Soldier in the Grande Armée: The Memoirs of Jakob Meyer during the Napoleonic Wars (1808–1813)." Zutot 19.1 (2022): 55-69.

- Schwarzfuchs, Simon. Napoleon, the Jews, and the Sanhedrin. Philadelphia 1979.

- Taieb, Julien. "From Maimonides to Napoleon: The True and the Normative." Global Jurist 7.1 (2007).

- Tozzi, Christopher. "Jews, soldiering, and citizenship in revolutionary and Napoleonic France." The Journal of Modern History 86.2 (2014): 233-257.

- Trigano, Shmuel. "The French Revolution and the Jews." Modern Judaism (1990): 171-190.

- Weider, Ben. "Napoleon and the Jews." The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society 1.2 (1998).

- Woolf, Stuart. "French civilization and ethnicity in the Napoleonic Empire." Past & Present 124 (1989): 96-120.

External links

edit- Napoleon and the Jews

- Labyrinthe. Atelier interdisciplinaire (a journal in French) published in 2007 a special issue dealing with the topic: Les Juifs contre l'émancipation. De Babylone à Benny Lévy.