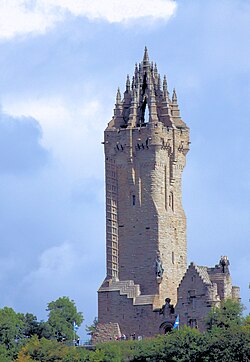

The National Wallace Monument (generally known as the Wallace Monument) is a 67 m (220 ft) tower on the shoulder of the Abbey Craig, a hilltop overlooking Stirling in Scotland.[1] It commemorates Sir William Wallace, a 13th- and 14th-century Scottish hero.[2]

| Wallace Monument | |

|---|---|

The tower in 2013 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Tower |

| Architectural style | Victorian Gothic |

| Location | Abbey Craig |

| Town or city | Stirling |

| Country | Scotland |

| Coordinates | 56°8′19″N 3°55′13″W / 56.13861°N 3.92028°W |

| Named for | William Wallace |

| Groundbreaking | 1861 |

| Completed | 1869 |

| Cost | £18,000 |

| Height | 67 m (220 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sandstone |

| Floor count | 4 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | John Thomas Rochead |

| Website | |

| nationalwallacemonument | |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Official name | Wallace Monument Abbey Craig |

| Designated | 4 November 1965 |

| Reference no. | LB41118 |

The tower is open to the public for an admission fee. Visitors approach by foot from the base of the crag on which it stands. On entry there are 246 steps to the final observation platform, with three exhibition rooms within the body of the tower. The tower is not accessible to disabled visitors.[2]

History

editThe tower was constructed following a fundraising campaign, which accompanied a resurgence of Scottish national identity in the 19th century. The campaign was begun in Glasgow in 1851 by Rev Charles Rogers, who was joined by William Burns. Burns took sole charge from around 1855 following Rogers' resignation. In addition to public subscription, it was partially funded by contributions from a number of foreign donors, including Italian national leader Giuseppe Garibaldi. The Victorian Gothic monument was created by architect John Thomas Rochead.[3]

The foundation stone was laid in 1861 by the Duke of Atholl in his role as Grand Master Mason of Scotland, with a short speech given by Sir Archibald Alison.[4] Abbey Craig, a volcanic crag above Cambuskenneth Abbey, was chosen for the location of the tower because it the location from which Wallace was said to have watched the gathering of the army of King Edward I of England just before the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297.

The sandstone tower, which is 67-metre (220-foot) tall, took eight years to build. It was completed in 1869 and cost £18,000[3] (about £1.8million in 2024).[5]

Visitor attraction

editThe monument is open to the general public. Visitors climb the 246-step spiral staircase to the viewing gallery inside the monument's crown, which provides expansive views of the Ochil Hills and the Forth Valley.

A number of artifacts believed to have belonged to Wallace are on display inside the monument, including the Wallace Sword, a 1.63 m (5 ft 4 in) longsword weighing almost three kilograms (seven pounds).[6] Inside is also a Hall of Heroes, a series of busts of famous Scots, effectively a small national Hall of Fame. The heroes[7] are Robert the Bruce, George Buchanan, John Knox, Allan Ramsay, Robert Burns,[8] Robert Tannahill, Adam Smith, James Watt, Sir Walter Scott, William Murdoch, Sir David Brewster, Thomas Carlyle,[9] Hugh Miller, Thomas Chalmers, David Livingstone, and W. E. Gladstone.[10] In 2017 it was announced that Mary Slessor and Maggie Keswick Jencks would be the first heroines to be celebrated in the hall.[11]

Sculptures of William Wallace

editThe original Victorian statue of Wallace stands on the corner of the monument and is by the Edinburgh sculptor David Watson Stevenson.[12]

Braveheart

editIn 1996 Tom Church carved a statue of Wallace called "Freedom", which was inspired by the film Braveheart.[13] It has the face of Mel Gibson, the actor who played William Wallace in the film. Church leased the statue to Stirling Council, who in 1997 installed it in the car park of the visitor centre at the foot of the craig.[13] The statue was deeply unpopular, being described as "among the most loathed pieces of public art in Scotland".[14] and was regularly vandalised[15] before being placed in a cage to prevent further damage. Plans to expand the visitor centre, including a new restaurant and reception, led to the unpopular statue's removal in 2008.[16] It was returned to Church, who, after an unsuccessful attempt to sell it at auction,[14] reportedly offered it to Donald Trump's Menie estate golf resort.[17] However, it remained in the garden of the sculptor's home, where it was incorporated into a replica of a castle, and with additions to it that included the head of the decapitated governor of York.[18] In April 2016, it was reported in local press that the statue might be moved to Ardrossan's old Barony Church.[19] In September 2021, it was moved to Glebe Park stadium in Brechin.[20]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Illustrated guide to Stirling and the national Wallace monument (9th ed.). Stirling: Mackay, Eneas. 1897. pp. 1–16.

- ^ a b "The National Wallace Monument". Your Stirling.

- ^ a b "DSA Building/Design Report: Wallace Monument". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ Logie: A Parish History, Menzies Fergusson, 1905

- ^ "What would goods and services costing £18000 in 1869 cost in April 2024?". www.bankofengland.co.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Scottish Wars of Independence". BBC Scotland. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Shearer's Stirling: historical and descriptive, with extracts from Burgh records and Exchequer Roll volumes, 1264 to 1529, view of Stirling in 1620, and an old plan of Stirling. Stirling: R.S. Shearer & Son. 1897. p. 114. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Harvey, William (1899). Robert Burns in Stirlingshire. Stirling: E. Mackay. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Masson, David (1891). Carlyle: the address delivered by David Masson on unveiling a bust of Thomas Carlyle in the Wallace Monument. Glasgow. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Hall of Heroes". National Wallace Monument. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "Scotland's Heroines – marking their place in history". National Wallace Monument. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "David Watson Stevenson RSA". sculpture.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b Kevin Hurley (19 September 2004). "They may take our lives but they won't take Freedom". Scotland on Sunday. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ a b "They may take our lives but they won't take Freedom".

- ^ "Wallace statue defaced". The Herald. 17 August 1998. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Wallace statue back with sculptor". BBC News. 16 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ Administrator, dailyrecord (23 April 2008). "Donald Trump to be given controversial William Wallace statue".

- ^ Bayer, Kurt (24 October 2009). "Sculptor's anger as thieves nick his Braveheart statue".

- ^ "Wallace statue and memorabilia to get new home in old Barony Church". Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald. 12 April 2016.

- ^ "Unveiling of Braveheart Statue". Brechin City FC. Retrieved 6 September 2021.