Ned Kelly is a 1970 British-Australian biographical bushranger film. It was the seventh Australian feature film version of the story of 19th-century Australian bushranger Ned Kelly,[5] and is notable for being the first Kelly film to be shot in colour.

| Ned Kelly | |

|---|---|

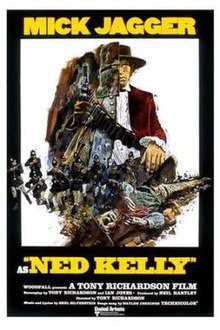

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tony Richardson |

| Screenplay by | Tony Richardson Ian Jones Uncredited: Alex Buzo[1] |

| Produced by | Neil Hartley |

| Starring | Mick Jagger |

| Cinematography | Gerry Fisher |

| Edited by | Charles Rees |

| Music by | Shel Silverstein |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | A$2.5 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $808,000 (Australia)[4] |

The film was directed by Tony Richardson, and starred Mick Jagger in the title role. Scottish-born actor Mark McManus played the part of Kelly's friend Joe Byrne. It was a British production, but was filmed entirely in Australia, shot mostly around Braidwood in southern New South Wales, with a largely Australian supporting cast.

Plot

editThis section needs an improved plot summary. (November 2024) |

Ned Kelly is forced by police persecution to become a bushranger. He robs several banks and is eventually captured after the Siege of Glenrowan. He is hanged in Melbourne.

Cast

edit- Mick Jagger as Ned Kelly

- Geoff Gilmour as Steve Hart

- Mark McManus as Joe Byrne

- McManus had previously played Dan Kelly in Ballad for One Gun (1963).

- Serge Lazareff as Wild Wright

- Peter Sumner as Tom Lloyd

- Ken Shorter as Aaron Sherritt

- James Elliott as Pat O'Donnell

- Clarissa Kaye as Mrs. Kelly

- Diane Craig as Maggie Kelly

- Sue Lloyd as Kate Kelly

- Alexi Long as Grace Kelly

- Ken Goodlet as Supt. Nicholson

- Goodlet had previously played Kelly in a 1960 telemovie.[6]

- Frank Thring as Judge Sir Redmond Barry

- Bruce Barry as George King

- Tony Bazell as Mr. Scott

- Allen Bickford as Dan Kelly

- Robert Bruning as Sgt. Steele

- Alexander Cann as McInnes

- Janne Wesley as Caitlyn

- Martyn Sanderson as Fitzpatrick

- John Laws as Kennedy

- Liam Reynolds as Lonigan

- Lindsay Smith as McIntyre

- John Gray as Stratton

- Gerry Duggan as Father O'Hea

- Nigel Lovell as Capt. Standish

- Reg Gorman as Bracken (uncredited)

Production

editDevelopment

editKarel Reisz and Albert Finney

editIn the early 1960s, Karel Reisz and Albert Finney announced plans to make a film about Ned Kelly from a screenplay by David Storey. Finney and Reisz flew to Australia in October 1962 and spent ten weeks picking locations and doing research.

In January 1963, it was reported the film would star Finney and Angela Lansbury.[7] The movie was meant to be Finney's next project after Tom Jones (1963) and filming was to start in March 1963.

The British arm of Columbia Pictures agreed to put up the entire budget. However, British labour union regulations required a mostly British crew, and the cost of putting them up in Australia put the budget beyond what Columbia were willing to pay. (Tom Jones had yet to be released.) Finney and Reisz went on to make Night Must Fall (1964) instead.[8]

Following this, Finney was still meant to make the film.[9] However, he and Reisz eventually dropped out.

Tony Richardson and Mick Jagger

editThe project passed on to Tom Jones director Tony Richardson, who wrote the script in collaboration with Ian Jones, a Melbourne writer and producer of TV drama and expert on Ned Kelly.[2] According to Kevin Brownlow, Ian McKellen was originally set to play the lead but the producers went for Mick Jagger.[10]

"I am taking this film very seriously", said Jagger at the time. "Kelly won't look anything like me. You wait and you'll see what I look like. I want to concentrate on being a character actor."[11]

During pre-production, other filmmakers announced their own Ned Kelly projects including Tim Burstall, Gary Shead and Dino de Laurentiis.[2]

Casting

editThe making of the film was dogged by problems; even before production began, Actors' Equity and some of Kelly's descendants protested strongly about the casting of Jagger in the lead role, and about the film's proposed shooting location in country New South Wales, rather than in Victoria, where the Kellys had lived.

Jagger's girlfriend of the time, Marianne Faithfull, had come to Australia to play the lead female role (Ned's sister, Maggie), but their relationship was breaking up, and she took an overdose of sleeping tablets soon after arrival in Sydney.[12] She was hospitalised in a coma, but recovered and was sent home.[13] She was replaced by a then-unknown Australian actress, Diane Craig, then studying at NIDA.[14]

Filming

editShooting began on 12 July 1969 and took ten weeks. During production, Jagger was slightly injured by a backfiring pistol, the cast and crew were dogged by illness, a number of costumes were destroyed by fire, and Jagger's co-star, Mark McManus, narrowly escaped serious injury when a horse-drawn cart in which he was riding overturned during filming.

Unlike most film versions, this is the first Ned Kelly film to feature the writing of "The Cameron Letter", one of Kelly's lesser-known and rarely published letters that was written to Donald Cameron, a member of the Parliament of Victoria. The letter was Kelly's first attempt to gain public sympathy. However, Kelly's well-known letter, The Jerilderie Letter, is omitted from the film.[15]

Release

editReception

editThe film was poorly received at its opening, and is still regarded as one of Richardson's least successful efforts. It was effectively disowned by Richardson and Jagger, neither of whom attended the London premiere.[16] As late as 1980 Jagger claimed he had never seen the film.[17] Gerry Fisher's cinematography, however, has been praised for its craftsmanship – repoussoir[clarification needed], shadow, reflection and understated lighting – giving the film a melancholy feel.

Arthur Krim of United Artists later did an assessment of the film as part of an evaluation of the company's inventory:

When we programmed this picture we thought Mick Jagger would be a big personality with the younger audience. Unfortunately, his other film Performance came out just before Ned Kelly and failed. We have every belief that Ned Kelly will not do well either. In addition, Tony Richardson, the filmmaker handled the material in a very slow-paced manner and we have not been able to persuade him to make the cuts necessary to improve the film. This is again a case of programming a film in a time of much greater optimism about the size of the so-called youth orientated – particularly starring one of the new folk heroes.[18]

A.H. Weiler of The New York Times said,

Ned Kelly bears all the signs of dedicated movie-making. Unfortunately, Mr. Richardson's direction and script, on which he collaborated with Ian Jones, do not delve too deeply into character. Nor are the principals' motivations projected with relevance to untutored American viewers. Ned Kelly, with intrusive, explanatory songs by Shel Silverstein sung by Waylon Jennings, emerges as somewhat pretentious folk-ballad fare that often explains little more than its action. ... Filmed in lovely colors on authentic Australian locales, Ned Kelly shimmers fitfully with varied beauties. A homecoming dance to a wild Irish reel is memorable, as are horsemen racing on a wooded hillside and a bare knuckle, friendly fight at a village fair. Equally impressive is the iron armor devised by Kelly as protection against pursuers. But these are colorful vignettes that only touch on but do not fully reveal the drama or the history behind the events.[19]

Filmink argued "Jagger was known as a wild child rock star but in the film played Ned Kelly as this languid… uh… I’m not sure what Jagger played Kelly as, to be honest, but it was not the same guy who sang 'Sympathy for the Devil'."[20]

Box office

editNed Kelly grossed $808,000 at the box office in Australia,[21] which is equivalent to $7,716,400 in 2009 dollars.

Home media

edit| Title | Format | Feature | Discs | Region 1 (USA) | Region 2 (UK) | Region 4/B (Australia) | Special Features | Distributors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ned Kelly | DVD | Film | 1 | 7 July 2015 | 2008 | 2005

14 February 2009 (Re-Release) |

None | Shock Entertainment (Australia)

MGM Home Entertainment (UK) |

| Ned Kelly | Blu-Ray | Film | 1 | N/A | N/A | 8 October 2021 | New Audio Commentary by film scholar Adrian Martin (2021)

New Interviews about the making of the film (2021) Trailer |

Via Vision Entertainment |

Legacy

editIan Jones later wrote and produced (with his wife Bronwyn Binns) a mini-series on Kelly, The Last Outlaw, which aired on the Seven Network in 1980. Australian actor John Jarratt starred as Kelly.[22]

The actual body armour costume worn by Jagger is on display at the Queanbeyan City Library, New South Wales, and the initials "MJ" are scratched on the inside.[23] The head-piece, like its original, was stolen.

Soundtrack

editThe Ned Kelly soundtrack features music composed by Shel Silverstein and performed by Kris Kristofferson and Waylon Jennings and produced by Ron Haffkine, with one solo track sung by Jagger and one sung by Tom Ghent.

Track listing

edit- Waylon Jennings – "Ned Kelly"

- "Such is Life"

- Mick Jagger – "The Wild Colonial Boy"

- "What Do You Mean I Don’t Like"

- Kris Kristofferson – "Son of a Scoundrel"

- Waylon Jennings – "Shadow of the Gallows"

- "If I Ever Kill"

- Waylon Jennings – "Lonigan's Widow"

- Kris Kristofferson – "Stoney Cold Ground"

- "Ladies and Gentlemen"

- Kris Kristofferson – "The Kelly's Keep Comin'"

- Waylon Jennings – "Ranchin' in the Evenin'"

- "Say"

- Waylon Jennings – "Blame it on the Kellys"

- Waylon Jennings – "Pleasures of a Sunday Afternoon"

- Tom Ghent – "Hey Ned"

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ pg 250 of "The Ned Kelly Encyclopaedia" by Justin Corfield

- ^ a b c Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998 p251

- ^ Davis, Ivor (10 August 1969). "Movies: Richardson, Jagger Feuding Down Under With Aussies". Los Angeles Times. p. 16.

- ^ 'Australian Films At the Australian Box office' Film Victoria Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine accessed 28 September 2012

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (24 July 2019). "50 Meat Pie Westerns". Filmink.

- ^ Essay "Films on Ned Kelly" by Justin Corfield, and published in "The Ned Kelly Encyclopaedia" (2003)

- ^ "FILMLAND EVENTS: Dunne Will Script 'Agony and Ecstasy'". Los Angeles Times. 14 January 1963. p. C12.

- ^ Alexander Walker, Hollywood England: The British Film Industry in the Sixties, Stein and Day, 1974 p 146-147

- ^ HOWARD THOMPSON (24 April 1963). "LANDAU CO. BUYING 2 FILM THEATERS: 'Quality' U.S. Films Set for 57th Street Properties Sites Sought 'Night Must Fall' Remake 2 Arrivals Today". The New York Times. p. 33.

- ^ Welsh, James Michael & Tibbetts, John C. The Cinema of Tony Richardson: Essays and Interviews SUNY Press, 1999, p. 38

- ^ "IT'S MICK ("NED KELLY") JAGGER". The Australian Women's Weekly. 23 July 1969. p. 18. Retrieved 18 September 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Paphides, Pete (6 March 2009). "Marianne Faithfull makes peace with her past – Times Online". The Times. London. Retrieved 19 July 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Whatever happened to MARIANNE FAITHFULL?". The Australian Women's Weekly. 25 February 1976. p. 20. Retrieved 18 September 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "STARS IN DIANE'S EYES". The Australian Women's Weekly. 30 July 1969. p. 12. Retrieved 18 September 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ http://www.kellygang.asn.au/people/peC/cameronDMLA.html Archived 30 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine at http://www.kellygang.asn.au/people/peC/cameronDMLA.html

- ^ 'Ned Kelly: How Mick Jagger Almost Ruined the Australian Icon', International Business Times, 1 sept 2011 accessed 18 September 2011

- ^ "Mick and the Stones [?]". The Australian Women's Weekly. 27 August 1980. p. 166 Supplement: FREE Your TV Magazine. Retrieved 18 September 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ quoted in Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company that Changed the Film Industry, Wisconsin Press, 1987 p 313-314

- ^ A.H. Weiler, "Jagger as Outlaw" Review, 8 October 1970

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (23 April 2023). "Barry Humphries – The First Proper Film Star of the Australian Revival". Filmink.

- ^ "Film Victoria // supporting Victoria's film television and games industry" (PDF). Film Victoria. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ "Ne[?]elly[?]isfit or murderer?". The Australian Women's Weekly. 8 October 1980. p. 24 Supplement: FREE Your TV Magazine. Retrieved 18 September 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Queanbeyan City Council". qcc.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

External links

edit- Ned Kelly at IMDb

- Ned Kelly at AllMovie

- Ned Kelly at Rotten Tomatoes

- Ned Kelly is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Ned Kelly (1970 film) at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Ned Kelly Archived 2 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine at Mickjagger.com

- Ned Kelly at Oz Movies

- Gaunson, Stephen (2010), ‘International Outlaws: Ned Kelly, Tony Richardson and the International co-production’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, Special Issue: ‘Australian International Pictures’, (eds) Adrian Danks and Constantine Verevis, 4.3, p. 253-263

- Geoff Stanton, 'Like a Rolling Stone: The Untold Story of the Kelly Gang' at From the Barrellhouse 25 April 2011