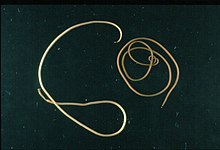

Nematomorpha (sometimes called Gordiacea, and commonly known as horsehair worms, hairsnakes,[1][2][3] or Gordian worms) are a phylum of parasitoid animals superficially similar to nematode worms in morphology, hence the name. Most species range in size from 50 to 100 millimetres (2.0 to 3.9 in), reaching 2 metres (79 in) in extreme cases, and 1 to 3 millimetres (0.039 to 0.118 in) in diameter. Horsehair worms can be discovered in damp areas, such as watering troughs, swimming pools, streams, puddles, and cisterns. The adult worms are free-living, but the larvae are parasitic on arthropods, such as beetles, cockroaches, mantises, orthopterans, and crustaceans.[4] About 351 freshwater species are known[5] and a conservative estimate suggests that there may be about 2000 freshwater species worldwide.[6] The name "Gordian" stems from the legendary Gordian knot. This relates to the fact that nematomorphs often coil themselves in tight balls that resemble knots.[7]

| Nematomorpha Temporal range: Possible Atdabanian Record

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Paragordius tricuspidatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Clade: | Nematoida |

| Phylum: | Nematomorpha Vejdovsky, 1886 |

| Orders and families | |

| |

Description and biology

editNematomorphs possess an external cuticle without cilia. Internally, they have only longitudinal muscle and a non-functional gut, with no excretory, respiratory or circulatory systems. The nervous system consists of a nerve ring near the anterior end of the animal, and a ventral nerve cord running along the body.[8]

Reproductively, they have two distinct sexes, with the internal fertilization of eggs that are then laid in gelatinous strings. Adults have cylindrical gonads, opening into the cloaca. The larvae have rings of cuticular hooks and terminal stylets that are believed to be used to enter the hosts. Once inside the host, the larvae live inside the haemocoel and absorb nutrients directly through their skin. Development into the adult form takes weeks or months, and the larva moults several times as it grows in size.[8]

The adults are mostly free-living in freshwater or marine environments, and males and females aggregate into tight balls (Gordian knots) during mating.[9][10]

In Spinochordodes tellinii and Paragordius tricuspidatus, which have grasshoppers and crickets as their hosts, the infection acts on the infected host's brain.[11] This causes the host insect to seek water and drown itself, thus returning the nematomorph to water.[9] P. tricuspidatus is also remarkably able to survive the predation of their host, being able to wiggle out of the predator that has eaten the host.[12] The nematomorpha parasite affects host Hierodula patellifera's light-interpreting organs so the host is attracted to horizontally polarized light. Thus the host goes into water and the parasite's lifecycle completes.[13] Many of the genes the parasites use for manipulating their host have been acquired through horizontal gene transfer from the host genome.[14]

There are a few cases of accidental parasitism in vertebrate hosts, including dogs,[15] cats,[16] and humans. Several cases involving Parachordodes, Paragordius, or Gordius have been recorded in human hosts in Japan and China.[17]

Community ecology

editOwing to their use of orthopterans as hosts, nematomorphs can be significant factors in shaping community ecology. One study conducted in a Japanese riparian ecosystem showed that nematomorphs can cause orthopterans to become 20 times more likely to enter water than non-infected orthopterans; these orthopterans constituted up to 60% of the annual energy intake for the Kirikuchi char. Absence of nematomorphs from riparian communities can thus lead to char predating more heavily on other aquatic invertebrates, potentially causing more widespread physiological effects.[18]

Taxonomy

editNematomorphs can be confused with nematodes, particularly mermithid worms. Unlike nematomorphs, mermithids do not have a terminal cloaca. Male mermithids have one or two spicules just before the end apart from having a thinner, smoother cuticle, without areoles and a paler brown colour.[19]

The phylum is placed along with the Ecdysozoa clade of moulting organisms that include the Arthropoda. Their closest relatives are the nematodes. The two phyla make up the group Nematoida in the clade Cycloneuralia. During the larval stage, the animals show a resemblance to adult kinorhyncha and some species of Loricifera and Priapulida, all members of the group Scalidophora.[20] The earliest Nematomorph could be Maotianshania, from the Lower Cambrian; this organism is, however, very different from extant species;[21] fossilized worms resembling the modern forms have been reported from mid Cretaceous Burmese amber dated to 100 million years ago.[22]

Relationships within the phylum are still somewhat unclear, but two classes are recognised. The five marine species of nematomorph are contained in Nectonematoida.[23] This order is monotypic containing the genus Nectonema Verrill, 1879: adults are planktonic and the larvae parasitise decapod crustaceans, especially crabs.[23] They are characterized by a double row of natotory setae along each side of the body, dorsal and ventral longitudinal epidermal cords, a spacious and fluid-filled blastocoelom and singular gonads.

The approximately 320 remaining species are distributed between two families,[24] within the monotypic class Gordioida. Gordioidean adults are free-living in freshwater or semiterrestrial habitats and larvae parasitise insects, primarily orthopterans.[23] Unlike nectonematiodeans, gordioideans lack lateral rows of setae, have a single, ventral epidermal cord and their blastocoels are filled with mesenchyme in young animals but become spacious in older individuals.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Heston, Joshua. "Horse Hair Snake". State of the Ozarks. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Troxell, W.H. (30 January 1903). "Erroneous Beliefs" (PDF). Emmitsburg Chronicle. No. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-09. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Ningewance, Pat (8–10 August 1996). "Naasaab Izhi-anishinaabebii'igeng conference report: a conference to find a common Anishinaabemowin writing system" (PDF). Toronto, Ontario: Literacy Ontario. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-22.

Girls, don't swim without pants or a hairsnake will enter you.

- ^ Hanelt, B.; Thomas, F.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A. (2005). "Biology of the phylum Nematomorpha". Advances in Parasitology. Vol. 59. pp. 243–305. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(05)59004-3. ISBN 9780120317592. PMID 16182867.

- ^ Zhang, Z.-Q. (2011). "Animal biodiversity: An introduction to higher-level classification and taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 7–12. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ^ Poinar Jr., G (January 2008). "Global diversity of hairworms (Nematomorpha: Gordiaceae) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 79–83. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9112-3. S2CID 37985613.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ^ a b Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 307–308. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ a b Thomas, F.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A.; Martin, G.; Manu, C.; Durand, P.; Renaud, F. (May 2002). "Do hairworms (Nematomorpha) manipulate the water seeking behaviour of their terrestrial hosts?" (PDF). Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 15 (3): 356–361. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.485.9002. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00410.x. S2CID 86278524. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. — according to Thomas et al., the "infected insects may first display an erratic behaviour which brings them sooner or later close to a stream and then a behavioural change that makes them enter the water", rather than seeking out water over long distances.

- ^ Schmidt-Rhaesa, Andreas (2002). "Two Dimensions of Biodiversity Research Exemplified by Nematomorpha and Gastrotricha". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 42 (3): 633–640. doi:10.1093/icb/42.3.633. PMID 21708759.

- ^ Thomas, F.; et al. (2003). "Biochemical and histological changes in the brain of the cricket Nemobius sylvestris infected by a manipulative parasite Paragordius tricuspudatus (Nematomorpha)". International Journal for Parasitology. 33 (4): 435–443. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00014-6. PMID 12705936.

- ^ Ponton, Fleur; Camille Lebarbenchon; Thierry Lefèvre; David G. Biron; David Duneau; David P. Hughes; Frédéric Thomas (April 2006). "Parasitology: Parasite survives predation on its host" (PDF). Nature. 440 (7085): 756. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..756P. doi:10.1038/440756a. PMID 16598248. S2CID 7777607.

- ^ "Parasites manipulate praying mantis's polarized-light perception, causing it to jump into water". phys.org. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- ^ This Parasitic Worm ‘Steals’ Genes From Its Unsuspecting Host

- ^ Hong, Eui-Ju; Sim, Cheolho; Chae, Joon-Seok; Kim, Hyeon-Cheol; Park, Jinho; Choi, Kyoung-Seong; Yu, Do-Hyeon; Yoo, Jae-Gyu; Park, Bae-Keun (2015). "A Horsehair Worm, Gordius sp. (Nematomorpha: Gordiida), Passed in a Canine Feces". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 53 (6): 719–24. doi:10.3347/kjp.2015.53.6.719. PMC 4725239. PMID 26797439.

- ^ Saito, Y; Inoue, I; Hayashi, F; Itagaki, H (1987). "A hairworm, Gordius sp., vomited by a domestic cat". Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science. 49 (6): 1035–7. doi:10.1292/jvms1939.49.1035. PMID 3430914.

- ^ Yamada, Minoru; Tegoshi, Tatsuya; Abe, Niichiro; Urabe, Misako (2012). "Two Human Cases Infected by the Horsehair Worm, Parachordodes sp. (Nematomorpha: Chordodidae), in Japan and America". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 50 (3): 263–7. doi:10.3347/kjp.2012.50.3.263. PMC 3428576. PMID 22949758.

- ^ Sato, Takuya; Watanabe, Katsutoshi; Kanaiwa, Minoru; Niizuma, Yasuaki; Harada, Yasushi; Lafferty, Kevin D. (2011). "Nematomorph parasites drive energy flow through a riparian ecosystem". Ecology. 92 (1): 201–207. doi:10.1890/09-1565.1. hdl:2433/139443. ISSN 1939-9170. PMID 21560690. S2CID 20274754.

- ^ Bryant, Malcolm S.; Adlard, Robert D.; Cannon, Lester R.G. (2006). "Gordian Worms: Factsheet" (PDF). Queensland Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-22. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ Nematomorpha – Bumblebees

- ^ Sun, W.; Hou, X. (1987). "Early Cambrian worms from Chengjiang, Yunnan, China: Maotianshania gen. nov" (Paywall). Acta Palaeontologica Sinica. 26 (3): 299–305.

- ^ Poinar George; Ron Buckley (September 2006). "Nematode (Nematoda: Mermithidae) and hairworm (Nematomorpha: Chordodidae) parasites in Early Cretaceous amber". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 93 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2006.04.006. PMID 16737709.

- ^ a b c Pechenik, 'Biology of the Invertebrates, 2010, pg 457.

- ^ "Gordioidea". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

General and cited references

edit- Pechenik, Jan A. (2010). "Four Phyla of Likely Nematode Relatives". Biology of the Invertebrates (6th International ed.). Singapore: Mc-Graw Hill Education (Asia). pp. 452–457. ISBN 978-0-07-127041-0.

Further reading

edit- Baker GL, Capinera JL (1997). "Nematodes and nematomorphs as control agents of grasshoppers and locusts". Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada. 171: 157–211. doi:10.4039/entm129171157-1.

- Hanelt, B.; Thomas, F.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A. (2005). "Biology of the phylum Nematomorpha". Advances in Parasitology. Vol. 59. pp. 243–305. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(05)59004-3. ISBN 9780120317592. PMID 16182867.

- Poinar GO Jr (1991). "Nematoda and Nematomorpha". In Thorp JH, Covich AP (eds.). Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 249–283.

- Thorne G (1940). "The hairworm, Gordius robustus Leidy, as a parasite of the Mormon cricket, Anabrus simplex Haldeman". Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 30: 219–231.

External links

edit- Capinera, J. L. Horsehair Worms, Hairworms, Gordian Worms, Nematomorphs, Gordius spp. (Nematomorpha: Gordioidea). University of Florida IFAS. Published 1999, revised 2005.

- Nematomorph worm – Behavior modification of cricket by nematomorph worm. YouTube.

- Gordian worms discussed on RNZ Critter of the Week, 6 November 2015