Sydney Conservatorium of Music

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2017) |

The Sydney Conservatorium of Music (SCM) — formerly the New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music, and known by the moniker "The Con" — is the music school of the University of Sydney. It is one of the oldest and most prestigious music schools in Australia, founded in 1915 by Belgian conductor and violinist Henri Verbrugghen.

Sydney Conservatorium of Music, as viewed from the Royal Botanic Gardens | |

Other name | The Con |

|---|---|

Former name | New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music |

| Type | Public Music school |

| Established | 1915 |

| Founders | |

Parent institution | University of Sydney |

Academic affiliation |

|

| Head of School and Dean | Anna Reid |

| Students | 1000 |

| Location | , , 33°51′48″S 151°12′52″E / 33.863455°S 151.214353°E |

| Website | sydney |

| |

Building details | |

| |

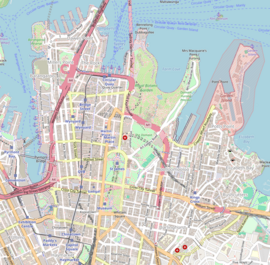

Location in Sydney central business district | |

| Former names | Stables for the First Government House |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Architectural style | Gothic Picturesque |

| Construction started | 9 August 1817 |

| Completed | 1820 |

| Client | Colonial Governor |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) | Chris Johnson |

| Renovating firm | NSW Government Architect with Daryl Jackson, Robin Dyke and Robert Tanner |

| References | |

| [1][2] | |

| Official name | Conservatorium of Music; Government House Stables; Governor's Stables |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Criteria | a., b., c., d., e., f., g. |

| Designated | 14 January 2011 |

| Reference no. | 1849 |

| Type | Stables |

| Category | Government and Administration |

The heritage-listed main building of the Conservatorium — the Greenway Building — is located within the Royal Botanic Gardens on Macquarie Street on the eastern fringe of the Sydney central business district. It also has teaching at the main campus of the University in Camperdown/Darlington, at the Seymour Centre and eventually the Footbridge Theatre.

The Greenway Building is also home to the community-based Conservatorium Open Academy and the Conservatorium High School. In addition to its secondary, undergraduate, post-graduate and community education teaching and learning functions, the Conservatorium undertakes research in various fields of music. The Building was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 14 January 2011.[1]

History

editThe land originally belonged to the Aboriginal people, called the "Eora", who lived around Sydney coast. They lived off the land by relying on its natural resources including the rich plants, birds, animals and marine life surrounding the Harbour within what is now the City of Sydney local government area the traditional owners are the Cadigal and Wangal bands of the "Eora". There is no written record of the name of their language spoken and currently, there are debates as to whether these people spoke a separate language or a dialect of the Dharug language.[1]

Governor Arthur Phillip arrived in 1788 with a pre-fabricated building which was assembled as his Government House, now partially on the current site of the Museum of Sydney and partially under Bridge Street. In its varied additions and permutations, it survived as the Sydney residence of the Governor until completion of the new Government House.[1]

Governor Lachlan Macquarie took control of the colony in 1810 using that building as his Sydney residence. On 18 March 1816, he reported that he had postponed any changes to convert Sydney Government House into adequate accommodation. He noted the poor condition of the building saying that "All the Offices, exclusive of being in a decayed and rotten State, are ill Constructed in regard to Plan and on Much too Small a Scale; they now exhibit a Most ruinous Mean, Shabby Appearance. No private Gentleman in the Colony is so Very ill Accommodated with Offices as I am at this Moment, Not having Sufficient Room to lodge a Very Small Establishment of Servants; the Stables; if possible, are still worse than the other Offices, it having been of late frequently Necessary to prop them up with Timber Posts to prevent it falling, or being blown down by the Winds." He noted that he wished to erect a new Government House and Offices in the Domain as soon as the Barracks was complete at the expense of the Police Fund.[3][1]

The then Secretary for the Colonies, Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst, soon responded, writing on 30 January 1817 that he needed to see a plan and estimate of costs before he could approve the erection.[4] In 1817, Macquarie resumed the sites of a bakehouse and mill on the proposed site. On 4 July 1817, he instructed a former convict, Francis Greenway, to prepare plans of offices and stables. Work commenced on the stables on 9 August 1817.[5] Macquarie replied to Bathurst on 12 December that he was disappointed with the lack of approval, but claimed that no construction had commenced due to heavy rains.[6] Macquarie laid the foundation stone for the stables on 16 December 1817.[7][1]

Though Francis Greenway was the designer, it was not solely his work. In December 1819, Greenway noted that Macquarie saw the elevation before work began, but that his wife Elizabeth Macquarie gave him details of the number of rooms needed so that he could make a suitable plan. By 1819, according to Greenway, the stables were virtually planned though the barn in the range had become a stable. It then held 30 horses plus the stallions in the octagonal Towers. He estimated the cost of the stables to be £9,000.[8] In a letter to the Australian of 28 April 1825, he identified Thornbury Castle as his model. A relative of Macquarie's wife, Archibald Campbell, had been a pioneer of the Gothic architectural style in the late 18th century when he erected Inveraray Castle and it may have had a greater influence on the design by Greenway.[9] Yet on 7 February 1821, Major Druitt reported that Governor Macquarie had not liked the ornamentation of the towers and the rich Cornish around the battlements.[10][1]

It was not until 24 March 1819 that Macquarie informed the Colonial Office that he had commenced building the stables, in contravention of a firm order from Bathurst. "I had so long Suffered such very great Inconvenience from the want of a Secure Stables for my Horses and decent sleeping places for my Servants, that I had been under the Necessity of building a regular Suite of Offices of this Description in a Situation Contiguous to and sufficiently Convenient for the present Old Government House, and also in one that will equally suit any New Government House that my Successors may he hereafter Authorised to Erect. These Stables are built on a Commodious tho" not expensive Plan, and I expect they will be Completed in about three Months hence.'[11] Horses were prized possessions and very valuable. They needed to be protected from the weather and made secure from thieves. Early in 1819 Lt John Watts was sent from England with plans and estimates, but these do not appear to have serviced.[12][1]

On 26 September 1819, Commissioner John Thomas Bigge arrived in the colony to report the effectiveness of transportation to NSW as a publishment for criminals. He was soon examining Macquarie's program of public works and his policy of fostering former criminals to fill positions of authority. Bigge objected to the construction of the stables in October 1819 but noted that the work was so far advanced that to halt it would be a waste.[13][1]

An 1820 plan held at the Mitchell Library is not a construction plan, but seem to show it in its finished state. It depicted the towers as accommodation for servants, plus a dairy next to one of the coach houses and accommodation for a dairy maid, cowman and lodge keeper.[14][1]

Architect Henry Kitchen was highly critical of the stables in evidence to Bigge on 29 January 1821 saying it was extravagant whilst not providing the accommodation needed. He described it as an "incorrect attempt in the style of the castellated Gothic" with an area 174 feet by 130 feet housing 28 horses, [plus coach houses cow house and servant's quarters.[15] The stables were complete in February 1821.[1]

Greenway is better known for his Georgian designs but he also created a number of buildings in the Gothic model. Of these, Forts Philip and Macquarie, Dawes Point Battery and the Parramatta Road Toll-gate have all been demolished. Only the Government House Stables survives of his Gothic buildings.[1][16]

After Macquarie's return to Britain in 1821, the Stables had mixed uses. On 25 May 1825, Governor Thomas Brisbane suggested to Earl Bathurst that the 'Gothic Building on the pleasantest side of the Scite of the Domain, which was intended for a Government Stables, is utterly useless at present from the great disproportion of the Establishment of the Government, may be advantageously improved into a Government residence.'[17] On 30 June 1825, Earl Bathurst permitted Governor Ralph Darling to erect a new Government House or to convert the Stables into one though the estimates of costs would have to be sent to Britain for approval.[18] Late in 1825, Brisbane had loaned the stables to the Australian Agricultural Company to temporarily house its livestock after it arrived.[1]

There are a number of artists' views of the stables. This derived from its position overlooking the harbour as part of a vista of Sydney. It also acknowledged the stables as a piece of Gothic architecture, both romantic and picturesque. Even more to the point, it highlighted its role as a "folly" in a managed landscape.[1]

The stables remained under utilised. Governor Richard Bourke sought approval in February 1832 to erect a new Government House near the stables by selling some of the Domain to raise funds.[19] He also suggested that rooms in the stables could accommodate some of the Government House servants.[20][1]

At an inquiry into the building of the new Government House in 1836, Colonel George Barney originally suggested converting the stables into offices but later changed his mind to recommend demolition. Construction of the new Government House from 1837 finally ensured that another building overshadowed the stables. After the erection of the New Government House, the stables were used to accommodate staff and horses.[1]

Panoramic views form the top of the Garden Palace Exhibition building taken in 1881 by Charles Bayliss are the only known views of the internal courtyard and layout of the stables.[21] Additions were made to the north side in the late 1870s or early 1880s.[1][22]

By about 1910, the building's role as a horse stables and staff accommodation was ending due to the increasing use of motor cars. In 1912 the government declared the building would become a museum whilst the Minister for Public Instruction suggested it as an Academy of Fine Arts but the proposal turned into a specialist Conservatorium of Music.[1]

From 1913 to 1915, work to convert it into a conservatorium to the design of R. Seymour Wells from the Government Architect's Office was undertaken, including the construction of a roof over the courtyard and the construction of a large auditorium. A new entrance of a cantilevered concrete awning was created and the former one removed. The windows and doors were altered considerably, though the castellated stuccoed exterior remained.[23] The conservatorium auditorium was officially opened on 6 April 1915.[24]Henri Verbrugghen was appointed as director on 20 May 1915 and teaching began on 6 March 1916.[25] The site was formerly dedicated with an area of 3 roods 20 perches for a conservatorium of music on 22 December 1916 but was revoked on 2 November 1917 for an enlarged area of 3 roods 31 perches.[26] The Conservatorium High School commenced in 1919.[1][27]

After consideration of various proposals to increase accommodation, the Carr Labor government decided to rebuild on the site in 1995. The enlarged building designed by NSW Government Architect Chris Johnson and the private partnership of Daryl Jackson, Robin Dyke and Robert Tanner was completed in 2001. Construction proceeded in tandem with a major archaeological investigation of the site of the extensions. Deep excavation around the original core of the building allowed the needs of accommodation be met while preserving views to the site. Technological solutions such as separating the building shell from the surrounding sandstone and resting much of the extensions on rubber pads allowed the special acoustic needs of the Conservatorium to be met despite its proximity to the Cahill Expressway and the underground railway line. The work won an Australian Award for Urban Design Excellence in 2002.[28][1]

Origins of the conservatorium

editIn 1915 the NSW Government under William Holman allocated £22,000 to the redevelopment of the stables into a music school. The NSW State Conservatorium of Music opened on 6 March 1916 under the directorship of the Belgian conductor and violinist Henri Verbrugghen, who was the only salaried staff member.[citation needed] The institution's stated aims were "providing tuition of a standard at least equal to that of the leading European Conservatoriums" and to "protect amateurs against the frequent waste of time and money arising from unsystematic tuition".[citation needed] The reference to European standards and the appointment of a European director was not uncontroversial at the time, but criticism soon subsided. By all accounts, Verbrugghen was hugely energetic: Joseph Post, later himself to be director, described him as "a regular dynamo, and the sort of man of whom you had to take notice the moment he entered the room".[citation needed] Enrolments in the first year were healthy with 320 "single-study" students and a small contingent of full-time students, the first diploma graduations occurring four years later. A specialist high school, the Conservatorium High School was established in 1918, establishing a model for music education across the secondary, tertiary, and community sectors which has survived to this day.[citation needed]

Verbrugghen's impact was incisive but briefer than had been hoped. When he put a request to the NSW Government that he be paid separate salaries for his artistic work as conductor of the orchestra (by then the NSW State Orchestra) and educational work as director of the conservatorium, the government withdrew its subsidies for both the orchestra and the string quartet that Verbrugghen had installed. He resigned in 1921 after taking the Conservatorium Orchestra to Melbourne and to New Zealand.

The conservatorium was home to Australia's first full-time orchestra, composed of both professional musicians and conservatorium students. The orchestra remained Sydney's main orchestra for much of the 1920s, accompanying many artists brought to Australia by producer J. C. Williamson, including the violinist Jascha Heifetz, who donated money to the Conservatorium library for orchestral parts. However, during the later part of the stewardship of Verbrugghen's successor, W. Arundel Orchard (director 1923–34), there were tensions with another emerging professional body, the ABC Symphony Orchestra, later to become the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, driven by the young, ambitious and energetic Bernard Heinze, Director-General of Music for the federal government's new Australian Broadcasting Commission.

In 1935, under Edgar Bainton (director 1934–48), the Conservatorium Opera School was founded, later performing works such as Verdi's Falstaff and Otello, Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Die Walküre, and Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande, among others. Under Sir Eugene Goossens (Director 1948–55), opera at the conservatorium made a major contribution to what researcher Roger Covell has described as " the most seminal years in the history of locally produced opera...". Although the most prominent musician to have held the post of director, Goossens' tenure was not without controversy.

Expansion and reforms

editUnder the direction of Rex Hobcroft (1972–82), the Conservatorium adopted the modern educational profile recognised today. Hobcroft's vision of a "Music University" was realised, in which specialised musical disciplines including both classical and jazz performance, music education, composition and musicology enriched each other.

In 1990, as part of the Dawkins Reforms, the Conservatorium amalgamated with the University of Sydney, and was renamed the Sydney Conservatorium of Music.

A 1994 review of the Sydney Conservatorium by the University of Sydney resulted in a recommendation that "negotiations with the NSW State Government about permanent suitable accommodation for the Conservatorium be pursued as a matter of urgency."[citation needed]

As in 1916, a wide range of sites were considered, many of them controversial. In May 1997, 180 years after Governor Macquarie laid the foundation stone for the Greenway Building, State Premier Bob Carr announced a major upgrade of the Conservatorium, with the ultimate goal of creating a music education facility equal to or better than any in the world. A team was assembled to work to that brief, resulting in a complex collaboration between various government departments (notably the Department of Education and Training and the Department of Public Works and Services), the Government Architect, US-based acoustic consultants Kirkegaard Associates, Daryl Jackson Robin Dyke Architects, the key users represented by the Principal and Dean of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, and the Principal of the Conservatorium High School, the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust and many others.[1][2]

Heritage listing

editThis article contains promotional content. (December 2022) |

As at 15 July 2009, the Conservatorium of Music is of State Heritage significance because the former Government House Stables is a notable example of Old Colonial Gothick architecture. It is a rare surviving example of the work of noted ex-convict architect Francis Greenway in the Old Colonial Gothick style. Greenway was instrumental in Macquarie accomplishing Macquarie's aim to transforming the fledgling colony into an orderly, well-mannered society and environment. It is the only example of a gothic building designed by Greenway still standing. The cost and apparent extravagance was one of the reasons Macquarie was recalled to Britain.[1]

The Conservatorium building also has strong associations with Macquarie's wife, Elizabeth, an influential figure in moulding the colony into a more ordered and stylish place under her husband and with the assistance of Greenway.[1]

Since the building was converted for use as a Conservatorium in 1916, it has been the core music education institution in NSW and has strong associations with numerous important musicians.[1]

Sydney Conservatorium of Music was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 14 January 2011 having satisfied the following criteria:[1]

- The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The Conservatorium of Music is of historic significance at a State level because when it was designed and built the building was a key element in Governor Lachlan Macquarie's grand vision to make Sydney into an attractive, well designed city. The design was a result of Macquarie's ideas with input from his wife Elizabeth and was executed by ex convict architect Frances Greenway. Greenway had a key role in implementing landmark elements of Macquarie's designs for churches and public buildings. The Stables was the first stage of Macquarie's plan for a New Government House and although this was not built, the Stables influenced the new Government House that was eventually built. After the building's conversion to the Conservatorium of Music it has been the principal music education institution in the State from 1916 onwards and continues to fulfil its role in the building originally modified for this purpose.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

The Conservatorium of Music is of State heritage significance through its association with Governor Lachlan Macquarie who commissioned the work, his wife Elizabeth who strongly influenced the design and ex convict architect Francis Greenway who designed the building. On 30 March 1816 Greenway was appointed as the colony's first "Civil Architect", the forerunning position to the Government Architect. In its role as the principal music education institution in NSW for many years it has strong and significant association with noted musicians and administrators such as Henry Verbrugghen and Eugene Goossens who were Directors of the Conservatorium.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The Conservatorium building is of aesthetic significance at a State level as it is a notable exemplar of the Old Colonial Gothick Picturesque style of architecture in Australia. In addition it is the only surviving example of this style of architecture designed by Francis Greenway. Its strong symmetry, battlemented parapet walls, squat towers, pointed arch and square headed openings, label moulded over windows make the building an aesthetically distinctive example of Old Colonial Gothick Picturesque style.[1]

The substantial size of the building for a stable, the use of the picturesque style and its location on the edge of the Governor's Domain demonstrate the ambition of Governor Macquarie in creating order and style in the town of Sydney. Once complete and lacking its accompanying new Government House, it was a landmark "folly" in a managed landscape inspiring young artists and adding a touch of romance to a colony seen by British eyes as devoid of legend and antiquity.[1]

The Conservatorium of Music continues to feature as a prominent landmark in the townscape and the Royal Botanic Gardens. It features as a focal point at the entry leading to Government House.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The Conservatorium of Music is of State heritage significance for its association with generations of noted Australian musicians. It was and continues to be a focus for musical activity attracting visiting performers to perform in the auditorium[1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The Conservatorium is of State heritage significance as its potential archaeological resource has not been exhausted despite extensive investigation. The results of archaeological investigations to date have revealed much about the early history and activity of the colony and many artefacts uncovered are displayed and interpreted in the new building.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Being the only surviving example of Francis Greenways design in the Old Colonial Gothic Picturesque style makes the Conservatorium of Music an rarity. It also appears to be the only extant stable block in the Sydney CBD which survives from the Macquarie period.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

The Conservatorium is of State heritage significance as a fine example of Old Colonial Gothic Picturesque and demonstrates the principal elements of this style in its strong symmetry, battlemented parapet walls, squat towers, pointed arch and square headed openings, label moulded over windows.[1]

Greenway Building

editThe Conservatorium of Music is a large building designed in the Early Colonial Gothic Picturesque style. Located on the western edge of the Royal Botanic Gardens, the building was originally designed to be the stables for the new Government House that Governor Macquarie hoped for but did not succeed in building. The stables were designed by Francis Greenway who was appointed as civil architect on 30 March 1816. Greenway may have taken some of his Gothic inspiration from his time working with John Nash in England, or from direction from Elizabeth Macquarie, who was well versed in architecture. Elizabeth's cousin too had been an English pioneer of the Gothic Revival design and his work influenced her husband Governor Macquarie in his attempts to give the young colony some order and style.[1]

The stables were designed as a castellated fort. As part of Macquarie's scheme was to transform Sydney into an attractive city, the stables were intended as part of a picturesque landscape suitable for a gentleman's residence that Macquarie envisaged around the Government House he wished to build. The construction is of masonry with a sandstone base below rendered walls. Squat towers mark the corners of the complex and divide the main elevation to mark the main entries to the building. The external walls are parapeted with battlements. The parapets to the towers have stylised machicolations below the cornice.[1]

Entries are through wide pointed arch openings on the north and south sides. Ground floor windows are pairs of three pane casement sashes below a topflight. Label moulds frame the top of the ground floor window openings. The first floor has smaller single sash windows, most directly below the cornice mouldings. Small single sash windows are in the towers. Some windows, probably the original and reconstructed windows have sandstone reveals and margins. Others have rendered reveals and margins. Some original sandstone reveals survive, primarily on the east side. The main entries to the former stables have pointed arch openings.[1]

The two storey ranges of rooms were arranged around a central courtyard. A few weals on the courtyard side of these ranges survive notably on the south side where they are left unrendered. The central courtyard was infilled and roofed over in 1913-1915 to house an auditorium as part of the conversion for the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. The new infill is a largely independent structure from the stables with rendered masonry walls supporting a hipped roof with ventilation gables at the east and west ends and topped by copper clad lanterns. Copper gutters are used with copper rainwater heads marked with the date 1914. Internally the building retains the general plan of the original with an outer ring of rooms around a corridor. The Verbruggen Hall is at the centre of the plan.[1]

Basement level additions in 2001 provide a landscaped court on the east and north sides of the building. A new entry structure to the south of the former stables building connects the original stables to the basement additions.[1]

Archaeological evidence of the roadway that led from First Government House to the stables has been conserved in the 2001 entry structure to the south of the original building. A water storage cistern dating from the 1790s remains in situ and the foundations of a c. 1800 mill and bakery owned by John Palmer remain under the floor of the Verbrugghen Hall. A collection of artefacts unearthed during the restoration works is housed in the conservatorium. The collection and in situ archaeology constitute part of this listing.[1]

History

editOriginally commissioned in 1815 as the stables for the proposed Government House, the oldest conservatorium building was designed by the convict architect Francis Greenway. Listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register[1] in the Gothic Picturesque architectural style with turrets, the building was described as a "palace for horses" and is a portrayal of the romantic vision of Governor Macquarie and the British architectural trends of the time. It is the only example of a gothic building designed by Greenway still standing. The cost and apparent extravagance was one of the reasons Macquarie was recalled to Britain. The stables, located close to picturesque Sydney Harbour, reflect the building techniques and the range of materials and skills employed during the early settlement era.[1]

At the time of its listing on the State Heritage Register, the building was given the following statement of significance:[1]

The Conservatorium of Music is of State Heritage Significance because the former Government House Stables is a notable example of Old Colonial Gothick architecture. It is a rare surviving example of the work of noted ex-convict architect Francis Greenway in the Old Colonial Gothick style. Greenway was instrumental in accomplishing Macquarie's aim to transform the fledgling colony into an orderly, well mannered society and environment. It is the only example of a gothic building designed by Greenway still standing. The cost and apparent extravagance was one of the reasons Macquarie was recalled to Britain.

The conservatorium building also has strong associations with Macquarie's wife, Elizabeth, an influential figure in moulding the colony into a more ordered and stylish place under her husband and with the assistance of Greenway.

Since the building was converted for use as a conservatorium in 1916, it has been the core music education institution in NSW and has strong associations with numerous important musicians.

— Statement of significance, New South Wales State Heritage Register.

Condition

editAlthough converted into a Conservatorium, a good deal of original fabric remains in a fair to good condition. Archaeological investigations that accompanied recent additions were extensive and included deep excavation around the building. Although subject to alteration to fit it out as a Conservatorium, a good deal of the original fabric remains extant and it is still perfectly legible as an Old Colonial Gothic building. Internally some of the original surfaces remain visible, though most have been covered to fit it out as a Conservatorium.[1]

Modifications and dates

edit- Cantilevered awning added to the west side 1913-1915, removed 2001

- Openings reconstructed 2001

- Conservatorium extended with basement rooms and new entry on south side 2001

- Upper floor openings in larger bays between towers added 2001

- Verbrugghen Hall refitted 2001

- West entry converted to window 2001

- Extensive deep excavation around the Conservatorium for extensions and archaeological excavation 1998 - 2001 removed most of the archaeological evidence from the immediate surrounds of the site.[1]

Centenary commissions

editTo mark the centenary of the Conservatorium in 2015, it commissioned 101 new works, the spread designed to represent those who have shaped music over the past 100 years. The first work in the series was John Corigliano's Mr Tambourine Man, based on the poetry of Bob Dylan, which was presented on 11 September 2009.[29]

Leadership

editThe past directors, principals and deans were:[30]

| Name | Title | Term start | Term end | Time in office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henri Verbrugghen | Director | 1916 | 1921 | ||

| W. Arundel Orchard | 1923 | 1934 | |||

| Edgar Bainton | 1934 | 1948 | |||

| Sir Eugene Goossens | 1948 | 1955 | |||

| Sir Bernard Heinze | 1957 | 1966 | |||

| Joseph Post | 1966 | 1971 | |||

| Rex Hobcroft | 1972 | 1982 | |||

| John Painter | 1982 | 1985 | |||

| John Hopkins | 1986 | 1991 | |||

| Ronald Smart | Principal | 1992 | 1994 | ||

| Ros Pesman | Acting Principal | 1994 | 1995 | ||

| Sharman Pretty | Principal and Dean | 1995 | 2003 | ||

| Professor Kim Walker | Dean & Principal | 2004 | 2011 | ||

| Karl Kramer | 2012 | 2015 | |||

| Professor Anna Reid | Head of School and Dean | 2015 | incumbent |

Students' Association

editBoth undergraduate and postgraduate students at the Conservatorium are represented politically and academically by the Conservatorium Students' Association. Founded in 1919 as the Conservatorium Students' Union, it oversees the majority of student culture for the school, and organises the annual Con Ball.

The Association manages the Common Room and two turrets (one for their office and the other for storage) at the back of the Greenway Building. Merchandise for the Conservatorium is also sold by the Association.

Elections for the Association occur annually in October, with the terms of the elected starting on 1 December. The current president is Alexander Poirier, the Vice-President is Cianna Walker, the Secretary is Theresa Xiao, and the Treasurer is Jacques Lombard.

Notable alumni

edit- Essie Ackland, contralto[31]

- Richard Bonynge, conductor[32]

- Alexander Briger, conductor

- Tony Buck, member of band The Necks

- Jorja Chalmers, saxophone and keyboards[33]

- Romola Costantino, piano[34]

- Carl Crossin, conductor, director of the Elder Conservatorium

- Iva Davies, frontman of band Icehouse

- Tania Davis, member of band Bond

- George Ellis, conductor, composer and orchestrator[35]

- Bryan Fairfax, conductor

- Richard Farrell, piano[34]

- Rhondda Gillespie, piano

- Julian Hamilton, band member of The Presets, The Dissociatives and Silverchair

- David Hansen, countertenor

- Michael Kieran Harvey, piano

- Erin Holland, Miss World Australia 2013

- Dulcie Holland, piano and composition

- Bryce Jacobs, film composer and guitarist

- Carmel Kaine, violin

- Constantine Koukias, composition

- Geoffrey Lancaster, fortepiano

- Indra Lesmana, Indonesian Jazz musician

- Cho-Liang Lin, violin

- Jade MacRae, voice

- Anthony Maydwell, harp

- Richard Meale, composition

- Nicholas Milton, conductor

- Sam Moran, former member of The Wiggles

- James Morrison, trumpeter

- Kim Moyes, band member of The Presets, The Dissociatives and Silverchair

- Muriel O'Malley, contralto and musical theatre actress[36]

- Margaret Packham Hargrave, poet, writer

- Geoffrey Parsons, piano

- Geoffrey Payne, trumpet

- Deborah Riedel, voice

- Kathryn Selby, piano

- Larry Sitsky, composition and piano

- Rai Thistlethwayte, lead singer of Thirsty Merc

- Katia Tiutiunnik, composer

- Richard Tognetti, violin

- Esme Tombleson (1917–2010), Member of Parliament in New Zealand, and multiple sclerosis advocate[37]

- Timmy Trumpet, DJ and producer

- Nathan Waks, cellist

- Christopher Willcock, composer of liturgical music

- Gerard Willems, piano

- Kim Williams, composition, clarinet

- Malcolm Williamson, composition and piano[34]

- Jamie Lee Wilson, singer-songwriter

- Rowan Witt, theatre and film actor

- Roger Woodward, piano, composition [34]

- Simone Young, conductor

Notable teachers

edit- Ole Bøhn, violin

- Winifred Burston, piano

- Edwin Carr, composition

- George De Cairos Rego (1858-1946) piano

- Ross Edwards, composition

- George Ellis, conducting

- Richard Goldner, viola

- Isador Goodman, piano

- Vladimir Gorbach, classical guitar

- Matthew Hindson, composition

- Kevin Hunt, jazz piano, composition

- Liza Lim, composition

- William Motzing, jazz

- Neal Peres Da Costa, historical performance

- Robert Pikler, violin and viola

- Goetz Richter, violin

- Daniel Rojas, composition

- Nancy Salas, piano and harpsichord

- Kathryn Selby, chamber music

- Natalia Sheludiakova, piano

- Lois Simpson, cello

- Howie Smith, jazz

- Paul Stanhope, composition

- Alexa Still, flute

- Alexander Sverjensky, piano[34]

- Ernest Truman[38][39]

- Carl Vine, composition

- Mark Walton, woodwind, performance

- Gordon Watson, piano

- Fred Werner (active 1909-1915)

- Wanda Wiłkomirska, violin

- Gerard Willems, piano

- Daniel Yeadon, chamber music and historical performance

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as "Conservatorium of Music". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01849. Retrieved 14 October 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ a b "Conservatorium of Music Including Interior and Grounds". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ HRA, 1, 9, p 70-71

- ^ HRA, 1,9, p 205

- ^ BT 27 p 6499

- ^ HRA, 1, 9. p718-719

- ^ HRA 1, 10, p813

- ^ Ritchie, 1971, vol 2, p 130, 132-133

- ^ Kerr and Broadbent, 1980, 941

- ^ BT 27 p 6306-6307

- ^ HRA, 1,10, p97

- ^ BT 19, p2966-2969

- ^ BT 19, p 2966-2969

- ^ ML VI/PUB/GOVS/1 120, 1820

- ^ Ritchie 1971, vol 2, p 141

- ^ Kerr and Broadbent, 1980, p 40

- ^ HRA, 1, 11, p 617

- ^ HRA, 1, 12, p 9

- ^ HRA, 1, 16, p539-540

- ^ HRA 1, 16, p 786

- ^ Casey and Lowe Vol. 1. 2002. pp 83–84

- ^ Casey and Lowe, Vol. 1 pp 85–86

- ^ Karskens, 1989, pp. 128-130.

- ^ Karskens, 1989 p144

- ^ Casel and Lowe Vol 1, 2002, p 96

- ^ NSWGG, 2 Nov 1917, 0 5994

- ^ Casey and Lowe, Vol2, 2002, p 98

- ^ http://www.music,usyd.edu.au/friends/visit.shtml [dead link]

- ^ Limelight, August 2009, p. 9

- ^ History of the Con

- ^ Moignard, Kathy (1993). "Ackland, Essie Adele (1896–1975)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 13. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- ^ "Richard Bonynge AC CBE". Melba Recordings. 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ "Living the dream". The University of Sydney. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e ADB:Alexander Sverjensky

- ^ Gregory Blaxell (31 July 2013). "Maestro conductor George Ellis serves up Greek treats in Ryde Hunters Symphony Orchestra concert". Northern District Times. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "A Gifted Queensland Artists". The Catholic Press. 17 June 1926. p. 45.

- ^ Gustafson, Barry (1986). The First 50 Years : A History of the New Zealand National Party. Auckland: Reed Methuen. p. 348. ISBN 0-474-00177-6.

- ^ "Truman, Ernest Edwin Philip (1869–1948)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "Truman, Ernest | the Dictionary of Sydney".

Sources

edit- Government House Stables. 1820.

- Broadbent, James; Hughes, Joy (1979). Francis Greenway Architect.

- Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd (2002). Archaeological Investigation Site Macquarie St Sydney, Vol 1: History and Archaeology.

- Collins, D. (2001). Sounds from the Stables: The story of Sydney's Conservatorium.

- Group State Projects NSW DPWS (1997). Conservation Management Plan - Sydney Conservatorium of Music formerly the Stables to Government House.

- Higginbotham, Edward (1992). Archaeological Report.

- Ireland, Tracy (1998). Archaeological Report.

- Karskens, Grace (1989). "The House on the Hill: the Conservatorium and First Class Music". In Coltheart, Lenore (ed.). Significant Sites: History and Public Works in NSW.

- Kerr, Joan; Broadbent, James (1980). Gothick Taste in the Colony of NSW.

- Attribution

- This Wikipedia article contains material from Conservatorium of Music, entry number 1849 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

External links

edit- Sydney Conservatorium of Music

- Daryl Jackson Robin Dyke

- Andrew Robson (2014). "Percy Grainger at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music [1935]". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2015.[CC-By-SA]