1968 New York City teachers' strike

The New York City teachers' strike of 1968 was a months-long confrontation between the new community-controlled school board in the largely black Ocean Hill–Brownsville neighborhoods of Brooklyn and New York City's United Federation of Teachers. It began with a one day walkout in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district. It escalated to a citywide strike in September of that year, shutting down the public schools for a total of 36 days and increasing racial tensions between blacks and Jews.

Thousands of New York City teachers went on strike in 1968 when the school board of the neighborhood, which is now two separate neighborhoods, fired nineteen teachers and administrators without notice. The newly created school district, in a heavily black neighborhood, was an experiment in community control over schools—those dismissed were almost all Jewish.

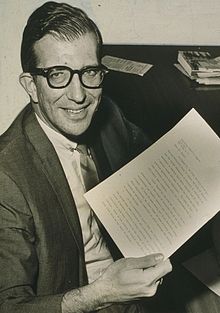

The United Federation of Teachers (UFT), led by Albert Shanker, demanded the teachers' reinstatement and accused the community-controlled school board of anti-semitism. At the start of the school year in September 1968, the UFT held a strike that shut down New York City's public schools for nearly two months, leaving a million students without schools to attend.

The strike pitted community against union, highlighting a conflict between local rights to self-determination and teachers' universal rights as workers.[1] Although the school district itself was quite small, the outcome of its experiment had great significance because of its potential to alter the entire educational system—in New York City and elsewhere. As one historian wrote in 1972: "If these seemingly simple acts had not been such a serious threat to the system, it would be unlikely that they would produce such a strong and immediate response."[2]

Background

editBrownsville

editFrom the 1880s through the 1960s, Brownsville was predominantly Jewish and politically radical. The Jewish population consistently elected socialist and American Labor Party candidates to the state assembly and was a strong supporter of unionized labor and collective bargaining. Margaret Sanger chose Brownsville as the site of America's first birth control clinic because she knew the community would be supportive.[3]

In 1940, blacks made up 6 percent of Brownsville's population, a portion that doubled over the next decade. Most of these new residents were poor and occupied the neighborhood's most undesirable housing.[4] Although the neighborhood was racially segregated, there was more public mixing and solidarity among blacks and Jews than could be found in most other neighborhoods.[5]

Around 1960, the neighborhood underwent a rapid demographic shift. Citing increased crime and their desire for social mobility, Jews left Brownsville en masse, to be replaced by more blacks and some Latinos. By 1970, Brownsville was 77 percent black and 19 percent Puerto Rican.[6] Furthermore, Brownsville was frequently ignored by black civil rights organizations such as the NAACP and Urban League[7] whose Brooklyn chapters were based in nearby Bedford-Stuyvesant and were overall less concerned with the issues of the lower income blacks who had moved into Brownsville, thus further isolating Brownsville's population. These changes corresponded to overall increases in segregation and inequality in New York City, as well as to the replacement of blue-collar with white-collar jobs.[8]

The newly black Brownsville neighborhood had few community institutions or economic opportunities. It lacked a middle class, and its residents did not own the businesses they relied upon.[9]

Schools

editWhites on the neighborhood's periphery lobbied with the school board against the building of a new school that would draw a racially diverse population. They were opposed by blacks, Latinos, and pro-integration whites, but nevertheless succeeded in functionally limiting the new school's racial makeup.[10]

In the years before the strike, Brownsville's schools had become extremely overcrowded, and students were attending in shifts.[11] Junior High School 271, which became the nexus of the strike, was constructed in 1963 to accommodate Brownsville's expanding population of youth. The school's performance was low from the outset, with most students testing below grade level in reading and math, and few advancing to the city's network of elite high schools.[12]

New York City's school system was controlled by the Central Board of Education, a large centralized bureaucracy.[13] It became clear to activists in the 1960s that the Central School Board was uninterested in pursuing mandatory integration; their frustration led them away from desegregation and into the struggle for community control.[14]

Teachers union

editBrownsville's teachers were members of the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), a new union local that had recently displaced the more leftist Teachers' Union (TU).[15][16] The TU, which contained active socialist and communist members, campaigned actively for racial equality, desegregation, and other radical political goals.[17]

The UFT held a philosophy of limited pluralism, according to which different cultures could maintain some individuality under the umbrella of an open democratic society. The union also championed individualist values and meritocracy.[18] Some called its policies 'race-blind' because it preferred to frame issues in terms of class.[19] The UFT contained a high proportion of Jews.[20]

Membership in the American Federation of Teachers, the national union of which the UFT is a part, had increased dramatically during the 1960s, as had the rate of teachers' strikes.[20]

In 1964, Bayard Rustin and Reverend Milton Galamison coordinated a citywide boycott of public schools to protest de facto segregation. Prior to the boycott, the organizers asked the UFT Executive Board to join the boycott or ask teachers to join the picket lines. The union, however, declined, promising only to protect from reprisals any teachers who participated. More than 400,000 New Yorkers participated in a one-day February 3, 1964, boycott, and newspapers were astounded both by the numbers of black and Puerto Rican parents and children who boycotted and by the complete absence of violence or disorder from the protestors. It was, a newspaper account accurately reported, "the largest civil rights demonstration" in American history, and, Rustin argued that "the movement to integrate the schools will create far-reaching benefits" for teachers as well as students. However, when protesters announced plans to follow up the February 3 boycott with a second one on March 16, the UFT declined to defend boycotting teachers from reprisals. Later, at the time of the 1968 school crisis, Brooklyn CORE leader Oliver Leeds and Afro-American Teachers Association President Al Vann would cite the UFT's refusal to support the 1964 integration campaign as proof that an alliance between the teachers' union and the black community was impossible.[21]

Black schools and teachers

editThe UFT's program for poor black schools was called "More Effective Schools". Under this program class sizes would shrink and teachers would double or triple up for individual classes. Although the UFT expected this program to be popular, it was challenged by the African-American Teachers Association (ATA; originally the Negro Teachers Association), a group whose founders in 1964 were also part of the UFT. The ATA felt that New York City's teachers and schools perpetuated a system of entrenched racism, and in 1966 it began campaigning actively for community control.[18] The UFT opposed both involuntary assignment and extra incentives for experienced teachers to come to poor schools.[22]

In 1967, the ATA opposed the UFT directly over the "disruptive child clause", a contract provision that allowed teachers to have children removed from classrooms and placed in special schools. The ATA argued that this provision exemplified and accelerated the system's overall racism. In the fall of 1967, the UFT held a two-week strike, seeking approval for the disruptive child clause; most of the ATA's members withdrew from the union. In February 1968, some ATA teachers helped to produce a tribute to Malcolm X that presented African music and dance, and glorified Black power; the UFT successfully asked that these teachers be disciplined.[18]

Community control

editIn the New York City school system, regulated by a civil service examination, only 8 percent of teachers and 3 percent of administrators were black.[23] Following Brown v. Board, 4,000 students in Ocean Hill–Brownsville were bused to white schools, where they complained of mistreatment.[24] Faith in the controllers of the school system sank lower and lower.[25]

Bolstered by the civil rights movement, but frustrated by resistance to desegregation, African Americans began to demand authority over the schools in which their children were educated. The ATA called for community-controlled schools, educating with a "Black value system" that emphasized "unity" and "collective work and responsibility" (as opposed to the "middle class" value of "individualism").[18] Leftist white allies, including teachers from the recently eclipsed Teachers Union, supported these demands.[26]

Mayor John Lindsay and wealthy business leaders, supported community control as a pathway to social stability.[23]) When in 1967 the Bundy Report, a creation of the Ford Foundation, recommended trying decentralization, the city decided to experiment in three areas—over the objections of some members of the white middle-classes, who disliked the ideological tendencies that black-controlled schools might embrace.[27]

The New York City Board of Education established the Ocean Hill–Brownsville area of Brooklyn as one of three decentralized school districts created by the city. In July 1967, the Ford Foundation issued Ocean Hill–Brownsville a $44,000 grant.[28] The new district operated under a separate, community-elected governing board with the power to hire administrators. If successful, the experiment could have led to citywide decentralization. While the local black population viewed it as empowerment against what it saw as an intransigent white bureaucracy, the teachers' union and other unions saw it as union busting—a reduction in the collective bargaining power of the union who would now have to deal with 33 separate, local bodies, rather than a central administration.[29]

Rhody McCoy, the new superintendent of the board, began working as a substitute teacher in 1949. He worked in the city's public school system ever since, as a teacher and then principal of a special needs school.[30] He told the New York Times he was gentle but ambitious, and eager to change schools for neglected children.[31] Some described him as a militant follower of Malcolm X,[32][33] and the UFT opposed the board's decision to appoint him in July 1967.[34] McCoy often frequented a mosque Malcolm X preached at and often visited the preacher's home.[35] McCoy was reported to be influenced by the Harold Cruise book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual and to believe Jews had too much influence in the civil rights movement.[36] McCoy nominated Herman Ferguson as the principal of JHS 271. Ferguson had penned an article in The Guardian in which he wrote his ideal school would have lessons on "instructions in gun weaponry, gun handling, and gun safety" as survival skills in a hostile society. The nomination was withdrawn.[35]

Curriculum and school environment

editEducational stratification in elementary schools was reduced significantly, with fewer grades being issued and one school even eliminating grade levels altogether. The curriculum began incorporating black and African history and culture, and some schools began offering instruction in Swahili and African counting. Additionally, one school with a large Puerto Rican student population became entirely bilingual.

Reports on the 1967–1968 school year were generally positive.[37] Visitors, students, and parents who supported the schools raved about the shift to student-focused education.[38]

However, the district still relied on the school board for funding, and many of its requests (e.g., for a telephone and new library books) were reportedly met slowly if at all.[39]

Teachers were taken aback by the level of control exercised by the school board, and many objected to the board's new policies concerning personnel and curriculum. The UFT opposed the new principals and denounced the Ocean Hill–Brownsville curriculum, saying that awareness of one's racial heritage would not be helpful in the job market.[18]

Personnel

editOnce created, the new administration of Ocean-Hill Brownsville began to select principals from outside the approved civil service list.[18] The schools appointed a racially diverse set of five new principals—including New York City's first Puerto Rican principal—winning broad support from the community but angering some teachers.[40]

In April 1968, the administration sought additional control over personnel, finance, and curriculum.[41] When the city did not grant these powers, the district's parents initiated a boycott of the schools.[42] The boycotts coincided with unrest due to the April 4 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[43][44] During disturbances in JHS 271 three teachers were injured.[35]

On May 9, 1968, the administration requested the transfer of 13 teachers and 6 administrators from Junior High School 271. The governing board accused these workers of attempting to sabotage the project.[45][46] All received short letters similar to the following, sent to teacher Fred Nauman:[47]

Dear Sir,

The governing board of the Ocean Hill–Brownsville Demonstration School District has voted to end your employment in the schools of the District. This action was taken on the recommendation of the Personnel Committee. This termination of employment is to take effect immediately.

In the event you wish to question this action, the Governing Board will receive you on Friday, May 10, 1968, at 6:00 P.M., at Intermedia School 55, 2021 Bergen Street, Brooklyn, New York.

You will report Friday morning to Personnel, 110 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, for reassignment.

- Sincerely,

- Rev C. Herbert Oliver, Chairman

- Ocean Hill–Brownsville Governing Board

- Rody A. McCoy

- Unit Administrator

This unilateral decision violated the rules of the union's contract.[48] The teachers were nearly unanimously Jewish. One black teacher included on the list, seemingly by accident, was quickly reinstated.[32] In total, 83 workers were dismissed from the Ocean Hill–Brownsville district.[49]

Parents in Brownsville generally supported the governing board.[39][50] Outsiders appreciated the black school board's attempt to regain control over its own school system.[32]

Shanker called the dismissals "a kind of vigilante activity" and said the schools had neglected due process. The Board of Education urged the teachers to ignore the letters.[45] Mayor John Lindsay issued a statement countermanding the district's decision and condemning "anarchy and lawlessness".[51] The dismissals were also condemned by the American Jewish Congress.[52]

Strikes

editMay

editWhen the teachers tried to return to the school, they were blocked by hundreds of community members and teachers who supported the administration's decision. One sign displayed in the window of the occupied school read, "Black people control your schools".[53] (At the same time, other teachers were staying off the job as per UFT instructions.)

On May 15, 300 police officers, including at least 60 in plainclothes, cordoned off the school (making five arrests), effectively breaking the parent blockade and allowing the teachers to return. The city's Board of Education and the Ocean Hill–Brownsville board both announced on the same day that the schools would close.[54]

From May 22–24, 350 UFT members stayed out of school in protest.[55][56] On June 20, these 350 strikers were also dismissed by the governing board.[57] Under the terms of the decentralization agreement, the teachers were returned to the control of the New York City public school system, where they sat idle in the school district offices.

September through November

editA series of citywide strikes at the start of the 1968 school year shut down the public schools for a total of 36 days. The union defied the new Taylor Law to go out on strike, and more than a million students were not able to attend school during strike days.

On September 9, 93 percent of the city's 58,000 teachers walked out. They agreed to return two days later after the Board of Education ordered the reinstatement of the dismissed teachers, but walked out again on September 13, once it became clear that the Board could not enforce this decision.[58]

Reactions

editBlack leadership

editThe NAACP announced support for the strike even though community control deviated from the official integrationist agenda.[59]

The strike did have support from black leaders Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, who had gained prominence in the labor movement as well as within the civil rights movement. Rustin and Randolph were shunned from the black community due to their position.[32]

Dissent within the UFT

editNot all UFT teachers supported the strike, and some actively opposed it with 1,716 union delegates opposing the strike and 12,021 supporting.[60] A statistical study published in 1974 found that teachers—white and Black—of Black students were significantly more likely to oppose the strike.[20] A coalition of black and Puerto Rican UFT members, supported by members of other local unions, released a statement supporting Ocean Hill–Brownsville and opposing the strike.[61]

Immediate effects

editOn schools

editIn Ocean Hill–Brownsville

editStudents and teachers returned to a chaotic atmosphere in the fall. Classes were held despite UFT picket lines outside.

Schools ran more smoothly in the Ocean Hill–Brownsville neighborhood than elsewhere, due to the fact that system was less reliant on the striking teachers and keys to the buildings.[62][63] The board hired new teachers to replace the strikers, including many local Jews, in an effort to prove that the district was not antisemitic.[2] The district's third graders were shown to have fallen from four months behind before community control to twelve months behind after it. The reading skills of the district's eighth graders were shown to have barely improved by the end of their time in ninth grade.[64]

When the original teachers were restored to their posts at JHS 271, students refused to attend their classes.[49][65] New York School Superintendent Bernard E. Donovan attempted to close schools in the district and to remove McCoy and most of the principals. When they refused to vacate their positions, Donovan called in the police.[49] The returning teachers were told to go to an auditorium to meet with Unit Administrator McCoy. When they arrived they were threatened and bullets were thrown at them by audience members, a pregnant teacher was punched in the stomach as she left the auditorium.[35]

In New York City at large

editStriking teachers were in and out of school during the first weeks of the year, affecting over one million students.[63]

Superintendent Donovan ordered many schools locked; in many places, people smashed windows and broke locks to re-enter their school buildings (sealed by union janitors sympathetic to the strike).[29] Some camped on school grounds overnight to prevent further lockouts by janitors and custodians. Some were arrested on trespassing charges.[63]

Other parents sent their children to Ocean Hill–Brownsville because the schools there were operational. Most of these outside students were black but some were white; some came long distances to attend the community–controlled schools.[66]

Racism and antisemitism

editShanker was routinely branded a racist, and many African-Americans accused the UFT of being 'Jewish-dominated'. A Puerto Rican group in the Ocean Hill–Brownsville neighborhood burnt Shanker in effigy.[63]

Shanker and some Jewish groups attributed the original firing of the teachers to antisemitism.[67] During the strike, the UFT distributed an official pamphlet called "Preaching Violence Instead of Teaching Children in Ocean Hill-Brownsville", citing a lesson that advocated Black separatism.[18] Shanker distributed 500,000 copies of a pamphlet some of his members found behind the schools in dispute worded "The Idea Behind This Program is Beautiful, But When the Money Changers Heard About It, They Took Over, As is Their Custom in the Black Community"[36]

On December 26, on radio station WBAI, Julius Lester interviewed Leslie Campbell, a history teacher, who read a poem written by one of his students entitled "Antisemitism: Dedicated to Albert Shanker" that began with the words "Hey, Jewboy, with that yarmulke on your head / You pale-faced Jew boy – I wish you were dead." The poem then goes on to say the author is sick about hearing about the Holocaust because it lasted only 15 years compared to the 400 years blacks had been suffering. Lester suggested he read that particular poem. Campbell asked Lester "Are you crazy?". Lester replied "No. I think it's important for people to know the kinds of feelings being aroused in at least one child because of what's happening in Ocean Hill-Brownsville."[68][69][70] The union filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission and tried to get Campbell fired. The incident further divided the black and Jewish Communities.[36]

Some members of the school community, as well as the New York Civil Liberties Union,[71] accused Shanker of playing up antisemitism to win sympathy and support.[72][73]

Of the district's new hires, 70 percent were neither Hispanic nor black, and half of these were Jewish.[71]

Resolution

editThe strike ended on November 17, when the New York State Education Commissioner asserted state control over the Ocean Hill–Brownsville district.[18] The dismissed teachers were reinstated, three of the new principals were transferred, and the trusteeship ran the district for four months.[74]

The conflict at Ocean Hill–Brownsville smoldered after the end of the strike. Eight people charged with harassing strikers counter-sued the city, alleging that law enforcement had been discriminatory and excessive.[75] In 1969 some charged that the schools underwent "a purge of militant black teachers".[76] When school opened in September 1969, the school district shut itself down for a day in protest of new regulations that deprived it of further autonomy.[77]

Aftermath

editIn the following weeks, hostility continued between the returning teachers and their students and replacement teachers. During the week of December 2 disorders by black students were reported in schools in four of the five of the city's boroughs as well in the New York City Subway. They were said to be instigated by a rally held by the City Wide Student Strike committee organized by Sonny Carson and JHS 271 teacher Leslie Campbell.[35]

Shanker emerged from the strike a figure of national prominence.[78] He was jailed for 15 days in February 1969 for sanctioning the strikes, in contravention of New York's Taylor Law. The Ocean Hill–Brownsville district lost direct control over its schools; other districts never gained control over their schools.[23]

The UFT crippled the ATA during the 1970s through a lawsuit, filed under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, accusing the ATA of excluding white teachers. The UFT also sought to cut off the ATA's sources of funding and remove its leaders from the school system.[18]

Residents of Brownsville continued to feel neglected by the city, and in 1970 some staged the "Brownsville Trash Riots".[79] When the schools agreed to impose a standardized reading test in 1971, its scores had fallen.[38]

The strike badly divided the city and became known as one of John Lindsay's "Ten Plagues".[29] Scholars have agreed with Shanker's assessment that "the whole alliance of liberals, blacks and Jews broke apart on this issue. It was a turning point in this way." The strike created a serious rift between white liberals, who supported the teachers' union, and blacks who wanted community control. The strike made it clear that these groups, previously allied in the Civil Rights Movement and the labor movement, would sometimes come into conflict.[24] Some groups allied with the civil rights movement and Black Liberation struggles moved towards the creation of independent African Schools, including The East's Uhuru Sasa Shule in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

According to historian Jerald Podair, these events also pushed New York's Jewish population into accepting an identity of whiteness, further polarizing race relations in the city. He argues that the shift in coalitions after the 1968 strike pushed New York City to the political right for decades to come—in part because race came to eclipse class as the main axis of social conflict.[23] The events surrounding the strike were a factor in the decision by Meir Kahane to form the Jewish Defense League.[36][80][81]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Green, Philip (Summer 1970). "Decentralization, Community Control, and Revolution: Reflections on Ocean Hill-Brownsville". The Massachusetts Review. 11 (3). The Massachusetts Review, Inc.: 415–441. JSTOR 25088003.

- ^ a b Gittell, Marilyn (October 1972). "Decentralization and Citizen Participation in Education". Public Administration Review. 32 (Curriculum Essays on Citizens, Politics, and Administration in Urban Neighborhoods): 670–686. doi:10.2307/975232. JSTOR 975232.

How fundamental was this effort at institutional change? At a minimum it attacked the structure on the delivery of services and the allocation of resources. At a maximum it potentially challenged the institutionalization of racism in America. It seriously challenged the "merit" civil service system which had become the main- stay of the American bureaucratic structure. It raised the issue of accountability of public service professionals and pointed to the distribution of power in the system and the inequities of the policy output of that structure. In a short three years, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville districts and IS 201, through such seemingly simple acts as hiring their own principals, allocating larger sums of money for the use of paraprofessionals, transfer- ring or dismissing teachers, and adopting a variety of new educational programs, had brought all of these issues into the forefront of the political arena.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, pp. 33–37.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 84.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Podair 2004, pp. 10–11: "The years after 1945 in New York were dominated by urban renewal. High-rise office buildings and white-collar employees began to replace tenement factories and working-class New Yorkers. These were also years in which centralization as an operational and philosophical tenet of municipal governance went virtually unchallenged in city life."

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 19: "Ocean Hill–Brownsville's social ills were a by-product of its boxed-in economic status. A contemporary observer was blunt: 'Brownsville has no middle class. ... There are no resident doctors, no resident lawyers; Negroes own less than 1 percent of the businesses.'"

- ^ Pritchett 2002, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 221.

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 19: "Reading and math scores were among the lowest in the city, with 73 percent of its pupils below grade level in reading and 85 percent in math. In a typical graduating class, only 2 percent went to the city's specialized high schools, which required applicants to pass written entrance examinations and served as feeders to major universities and the city colleges."

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 23: "The culture of centralization may have been more entrenched in New York's public education system more than anywhere else in the city. By the early 1960s, the system had become a classic example of top-heavy bureaucracy."

- ^ Podair 2004, pp. 32–33: "Given a choice between angering politically potent white voters or a marginalized black community, the board, predictably, took the path of least resistance. By 1966, with the campaign to integrate the city's public school at a dead end, Galamison, EQUAL, and New York's civil rights activists searched for new goals and strategies."

- ^ The UFT won the right to represent NYC teachers for the purpose of collective bargaining in 1961: Kelly, Mark (December 18, 1961). "N.Y. Teachers Pick AFL-CIO Union: Vote Results". Christian Science Monitor. p. 11. ProQuest 143064304.

Hereafter, when the 43,500 public schoolteachers of this city want to negotiate with the Board of Education regarding salary, pension, and other working rights, they will do so through the United Federation of Teachers, AFL–CIO.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 223.

- ^ Johnson, Lauri (Summer 2004). "A Generation of Women Activists: African American Female Educators in Harlem, 1930–1950". The Journal of African American History. 89 (3, "New Directions in African American Women's History"). Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.: 223–240. doi:10.2307/4134076. JSTOR 4134076. S2CID 144188669.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Podair, Gerald (Spring 1994). "White Values, "Black" Values: The Ocean Hill-Brownsville Controversy and New York City Culture, 1965–1975". Radical History Review. 1994 (59): 36–59. doi:10.1215/01636545-1994-59-36.

- ^ Perlstein, Daniel H. (2004). "Race, Class, and the Triumph of Teacher Unionism". Justice, justice : schools politics and the eclipse of liberalism. New York: P. Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-6787-0.

- ^ a b c Ritterband, Paul (Spring 1974). "Ethnic Power and the Public Schools: The New York City School Strike of 1968". Sociology of Education. 47 (2). American Sociological Association: 251–267. doi:10.2307/2112107. JSTOR 2112107.

- ^ Daniel Perlstein "The dead end of despair: Bayard Rustin, the 1968 New York school crisis, and the struggle for racial justice"

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Podair, Jerald E. (October 5–7, 2001). "The Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis: New York's Antigone" (PDF). Like Strangers: Blacks, Whites and New York City's Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis. CUNY Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave., @ 34th St.: Conference on New York City History. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Childs, Andrew Geddings (August 21, 2008). Ocean Hill-Brownsville and the Change in American Liberalism (M.A.). Florida State University DigiNole Commons. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Gittell, Marilyn (1968). "Community Control of Education". Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science. 29 (1. Urban Riots: Violence and Social Change): 60–71. doi:10.2307/3700907. JSTOR 3700907.

- ^ Podair 2004, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Podair 2004, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 229.

- ^ a b c "John Lindsay's Ten Plagues". Time. November 1, 1968. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 3.

- ^ "Ambitious' Educator: Rhody Arnold McCoy Jr". The New York Times. May 14, 1968. p. 44. ProQuest 118398846.

- ^ a b c d Kahlenberg, Richard D. (April 25, 2008). "Ocean Hill-Brownsville, 40 Years Later". Chronicle of Higher Education. ProQuest 214661029.

- ^ Maeder, Jay (June 1, 2001). "Absolute Control". NY Daily News. Retrieved August 14, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Cannato, Vincint (2001). "Community Control and the 1968 Teacher Strikes The Debacle at Ocean-Hill Brownsville". The Ungovernable City John Lindsey and His Struggle to Save New York. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465008438.

- ^ a b c d When They Come for Us, We'll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry by Gal Beckerman

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 230. "The 1967–1968 school year was a period of positive change in Ocean Hill–Brownsville schools, according to the Ford Foundation and other evaluators. Ford reviewers felt that Rhody McCoy was 'strong and capable,' and the board was 'consistent in its approach'. Given its limited financial support, the governing board appeared to be functioning 'as well as can be expected.' The New York City Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) also reported positive changes at Ocean Hill–Brownsville schools."

- ^ a b Ravich, Diane (1973). "Community Control Revisited". In Donna E. Shalala, Andrew Fishel (ed.). Readings in American Politics and Education. Ardent Media. ISBN 978-0-8422-0342-5. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ a b Mayer, Martin (May 19, 1968). "Frustration Is the Word For Ocean Hill". The New York Times. ProQuest 118166134.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 230. "The governing board appointed, over the objections of the UFT, five new principals: one white, two black, one Chinese, and the first Puerto Rican in the city. The Latino principal, Luis Fuentes, struggled to gain the support of the teachers, but, according to the CCHR, he 'quickly gained the respect of the students, parents, and the community. By establishing a rapport with Spanish-speaking parents, the principal served students for whom English was a second language. Parent participation increased dramatically as a result of his efforts."

- ^ Farber, M. A. (April 3, 1968). "Boycott of Experimental Schools Is Threatened Over Control". The New York Times. p. 27. ProQuest 118184554.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (April 12, 1968). "Brooklyn Pupils Stay Out 2d Day: Parents Keep Up Pressure for Control at 8 Schools". The New York Times. p. 49. ProQuest 118203653.

- ^ Gansberg, Martin (April 11, 1968). "More Blazes Set in Brownsville: Firemen Blame Rampaging Teen-Agers for Arson". The New York Times. p. 36. ProQuest 118179437.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (April 14, 1968). "Pressure by Boycott for Local Control". The New York Times. p. E13. ProQuest 118271556.

- ^ a b Bigart, Homer (May 10, 1968). "Negro School Panel Ousts 19, Defies City: Negro Unit Tries to Oust Teachers". The New York Times. p. 1. ProQuest 118362090.

- ^ Kifner, John (December 1, 1968). "Militant Priest of Ocean Hill Decries 'Bureaucracy'". The New York Times. p. 153. ProQuest 118371734.

- ^ Podair 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Berube, Maurice R. and Marilyn Gittell. Confrontation at Ocean Hill-Brownsville; the New York school strikes of 1968 New York, Praeger [1969] OCLC: 19279

- ^ a b c Buder, Leonard (October 10, 1968). "Donovan Orders J.H.S. 271 Closed After Disorders: Says Teaching 'Just Cannot Go On at Tumultuous School in Ocean Hill". The New York Times. pp. 1, 41. ProQuest 118402718.

- ^ Johnson, Thomas A. (September 16, 1968). "Brownsville Negroes See Need for District Board". The New York Times. ProQuest 118425511.

- ^ Lindsay, John (May 15, 1968). "Statement by the Mayor". The New York Times. p. 44. ProQuest 118303275.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (May 11, 1968). "11 Teachers Defy Local Dismissals: Six Supervisors Ousted by Experimental Board in Brooklyn Also Show Up". The New York Times. p. 1. ProQuest 118489094.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (May 15, 1968). "Parents Occupy Brooklyn School As Dispute Grows: Negroes Blocking Doors of J. H. S. 271 Keep Ousted Teachers From Entering". The New York Times. p. 1. ProQuest 118344798.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (May 16, 1968). "3 Schools Closed to Ease Tensions in Brooklyn Area: Local Board Counters City Action by Ordering All 8 in Test District to Shut: Police Break Blockade: 5 Ousted Teachers Escorted Into J.H.S. 271—Hundreds of Pupils are Kept Home". The New York Times. pp. 1, 41. ProQuest 118436282.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (May 23, 1968). "'Ousted' Teachers Are Backed by 350 in Union Walkout: Shanker, Charging Lockout, Vows None Will Return Until Allowed to Teach M'Coy Charges a 'Lie' Says Brooklyn Instructors Left After Ignoring Call to 'Clarify Situations'". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ Buder, Leonard (May 28, 1968). "Teachers Call For a New Boycott After McCoy Suspends 7 in Brooklyn". The New York Times. p. 18. ProQuest 118270346.

- ^ Currivan, Gene (June 21, 1968). "Ocean Hill Unit 'Dismisses' 350: McCoy Notifies Teachers". The New York Times. p. 24. ProQuest 118259826.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 231.

- ^ Allen, Walter R.; Joseph O. Jewell (Winter 1995). "African American Education since "An American Dilemma"". Daedalus. 124 (1–An American Dilemma Revisited): 77–100. JSTOR 20027284.

- ^ Stivers, Mike (September 12, 2018). "Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Fifty Years Later". Jacobin. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Negro Unionists Back Ocean Hill: Break With Central Labor Council on Teacher Strike". The New York Times. October 26, 1968. p. 24. ProQuest 118385356.

- ^ Farber, M. A. (September 10, 1968). "Brownsville has school as usual". The New York Times. ProQuest 118336755.

- ^ a b c d Buder, Leonard (October 19, 1968). "Parents Smash Windows, Doors to Open Schools". The New York Times. pp. 1, 26. ProQuest 118354804.

- ^ Goldstein, Dana (2014). "'We Both Got Militant': Union Teachers Versus Black Power During the Era of Community Control". The Teacher Wars: A History of America's Most Embattled Profession. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-53696-7.

- ^ Sometimes the students were led into a separate room by a co-teacher: Fox, Sylvan (October 1, 1968). "Some Hostility Marks Return Of 83 Teachers to Ocean Hill". The New York Times. ProQuest 118344028.

- ^ Johnson, Rudy (November 5, 1968). "Some pupils sent to Brownsville". The New York Times. ProQuest 118329655.

- ^ Treiman, Daniel (May 30, 2008). "Al Shanker and the Strike of 1968". Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

I didn't find strong evidence of this, but there was some interesting reaction and split within the Jewish community over Ocean Hill-Brownsville. It tended to be upper-middle-class Jews who were much more supportive of the Black Power movement than lower-middle-class Jews in the outer boroughs who saw Shanker as a hero for standing up to the Black Power movement. But I think the fact that he knew what antisemitism was all about as a child — and there was one point at which he was strung up in a tree, just horrible incidents — so he wasn't going to just kind of dismiss it, the way some more privileged Jews had. There was a sense among some upper-middle-class liberals — Jewish and non-Jewish — that, well, we can overlook black antisemitism, because look what they've gone through. I think that was an insulting way to look at that issue, that discrimination had to be taken seriously no matter what the source was, and that Al Shanker was right on this.

- ^ The Soul That Wanders New York Times January 31, 1988

- ^ Jewish Identity and The JDL. by Janet L. Dugan

- ^ Displays of Power Controversy from Enola Gay to Sensation by Steven C. Dubin

- ^ a b Pritchett 2002, p. 233.

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold H. (February 17, 1969). "Racism Aired at Rally Backing Community Control of Schools". The New York Times. p. 68. ProQuest 118671613.

Mrs. Frances Julty, a Negro leader of the Union of Concerned Parents, charged that racism by Albert Shanker, president of the United Federation of Teachers, helped turn the Jewish community into 'an armed camp' in the city. ... Complaining that the issue of black anti-Semitism had been distorted and inflated to the chagrin of Negroes, Mrs. Julty said, 'We don't condone it, and we don't agree with it, but damn it, we won't take responsibility for it.'

- ^ Kifner, John (December 22, 1996). "Echoes of a New York Waterloo". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 235.

- ^ They charged the city with incarcerating them unnecessarily and argued that the real obstruction of government had been the strike itself: Sibley, John (December 31, 1968). "8 Ocean Hill Negroes File Suit, Charging Indictment Conspiracy". The New York Times. ProQuest 118224603.

- ^ Handler, M. S. (July 3, 1969). "Ocean Hill Board Member Quits, Charging 'Atmosphere of Fear'". The New York Times. p. 27. ProQuest 118603484.

- ^ Delaney, Paul (September 13, 1969). "Ocean Hill Shuts Schools for Day: Local Board Protests Cut in Welfare and Failure to Get Teachers It Wants". The New York Times. ProQuest 118651420.

- ^ "Public Schools: Strike's Bitter End". Time. November 29, 1968.

- ^ Pritchett 2002, p. 239.

- ^ Terrorism 2000/2001 FBI

- ^ Terrorist Organization Profile: Jewish Defense League University of Maryland

- Eisenstadt, Peter R. (2010). Rochdale Village: Robert Moses, 6,000 Families, and New York City's Great Experiment in Integrated Housing. N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801448782.

- Isaacs, Charles S. (2014). Inside Ocean Hill–Brownsville: A Teacher's Education, 1968–69. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-5296-8.

- Kahlenberg, Richard D. (2009). Tough Liberal Albert Shanker and the Battles over Schools, Unions, Race, and Democracy. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13497-2.

- Podair, Jerald (2004). The Strike That Changed New York. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10940-5.

- Pritchett, Wendell (2002). Brownsville, Brooklyn : Blacks, Jews, and the changing face of the ghetto ([Nachdr.] ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-68446-6.

Further reading and listening

edit- Berube, Maurice, and Marilyn Gittell, ed. Confrontation at Ocean Hill-Brownsville (Frederick Praeger, 1969).

- Biondi, Martha. To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City (Harvard UP, 2003).

- Buffett, Neil Philip. "Crossing the Line: High School Student Activism, the New York High School Student Union, and the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville Teachers' Strike" Journal of Urban History (Dec 2018) https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144218796455

- Cannato, Vincent J. The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York (Basic Books, 2001). pp. 301–373.

- Edgell, Derek. The Movement for Community Control of New York City's Schools, 1966–1970: Class Wars (Edwin Mellen Press, 1998)

- Freedman, Max and Griffith, Mark Winston Griffith. Black Parents Take Control, Teachers Strike Back (February 5, 2020) and its second part (February 12, 2020), a two part podcast produced by NPR's Code Switch.

- Gittell, Marilyn, and Maurice Berube, eds., Confrontation at Ocean Hill-Brownsville (Praeger, 1969)

- Goldstein, Dana. Teacher Wars A History of Americas Most Embattled Profession (2014)

- Gordon, Jane Anna. Why They Couldn't Wait: A Critique of the Black–Jewish Conflict Over Community Control in Ocean-Hill Brownsville, 1967–1971. (RoutledgeFalmer, 2001). ISBN 0-415-92910-5

- Jacoby, Tamar. Someone Else's House: America's Unfinished Struggle for Integration (Free Press, 1998), pp. 158–226.

- Kahlenberg, Richard D. Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles Over Schools, Unions, Race, and Democracy (Columbia UP, 2007). ISBN 0-231-13496-7

- Podair, Jerald. " 'White' Values, 'Black' Values: The Ocean Hill–Brownsville Controversy and New York City Culture, 1965–1975," Radical History Review 59 (Spring 1994): 36–59

- Perlstein, Daniel. Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (Peter Lang, 2004)

- Perlstein, Daniel. "Community Control of Schools" in Encyclopedia of African American Education, ed by Kofo Lomotey (Sage, 2010) pp 182–184.

- Ravitch, Diane. The great school wars: A history of the New York City public schools (1974) partly online pp 308–391. Also see full text online

Primary sources

edit- Isaacs, Charles S. Inside Ocean Hill–Brownsville: A Teacher's Education, 1968–69 (SUNY Press, 2014)

- McCoy, Rhody. "Analysis of Critical Issues and Incidents in the New York City School Crisis, 1967–1970, and Their Implications for Urban Education" (Ed.D. dissertation., University of Massachusetts; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971. 7125304.)

- Rossner, Robert. The Year Without An Autumn: Portrait of a School in Crisis (R. N. Baron, 1969).