Obstructive lung disease is a category of respiratory disease characterized by airway obstruction. Many obstructive diseases of the lung result from narrowing (obstruction) of the smaller bronchi and larger bronchioles, often because of excessive contraction of the smooth muscle itself. It is generally characterized by inflamed and easily collapsible airways, obstruction to airflow, problems exhaling, and frequent medical clinic visits and hospitalizations. Types of obstructive lung disease include asthma, bronchiectasis, bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Although COPD shares similar characteristics with all other obstructive lung diseases, such as the signs of coughing and wheezing, they are distinct conditions in terms of disease onset, frequency of symptoms, and reversibility of airway obstruction.[1] Cystic fibrosis is also sometimes included in obstructive pulmonary disease.[2]

| Obstructive lung disease | |

|---|---|

| |

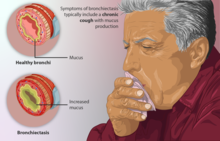

| Depiction of a person with bronchiectasis, a type of obstructive lung disease | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

Types

editAsthma

editAsthma is an obstructive lung disease where the bronchial tubes (airways) are extra sensitive (hyperresponsive). The airways become inflamed and produce excess mucus and the muscles around the airways tighten making the airways narrower. Asthma is usually triggered by breathing in things in the air such as dust or pollen that produce an allergic reaction. It may be triggered by other things such as an upper respiratory tract infection, cold air, exercise, or smoke. Asthma is a common condition and affects over 300 million people around the world.[3] Asthma causes recurring episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning.[4]

- Exercise-induced asthma is common in asthmatics, especially after participation in outdoor activities in cold weather.

- Occupational asthma – an estimated 2% to 5% of all asthma episodes may be caused by exposure to a specific sensitizing agent in the workplace.

- Nocturnal asthma is a characteristic problem in poorly controlled asthma and is reported by more than two-thirds of sub-optimally treated patients.

A peak flow meter can record variations in the severity of asthma over time. Spirometry, a measurement of lung function, can provide an assessment of the severity, reversibility, and variability of airflow limitation, and help confirm the diagnosis of asthma.[3]

Bronchiectasis

editBronchiectasis refers to the abnormal, irreversible dilatation of the bronchi caused by destructive and inflammatory changes in the airway walls. Bronchiectasis has three major anatomical patterns: cylindrical bronchiectasis, varicose bronchiectasis and cystic bronchiectasis.[5]

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

editChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), previously known as chronic obstructive airways disease (COAD) or chronic airflow limitation (CAL), is a group of illnesses characterised by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. The flow of air into and out of the lungs is impaired.[6] This can be measured with breathing devices such as a peak flow meter or by spirometry. Most people with COPD have characteristics of emphysema and chronic bronchitis to varying degrees. Asthma being a reversible obstruction of airways is often considered separately, but many COPD patients also have some degree of reversibility in their airways.[7]

In COPD, there is an increase in airway resistance, shown by a decrease in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) measured by spirometry. COPD is defined as a forced expiratory volume in 1 second divided by the forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) that is less than 0.7 (or 70%).[8] The residual volume, the volume of air left in the lungs following full expiration, is often increased in COPD, as is the total lung capacity, while the vital capacity remains relatively normal. The increased total lung capacity (hyperinflation) can result in the clinical feature of a barrel chest – a chest with a large front-to-back diameter that occurs in some individuals with emphysematous COPD. Hyperinflation can also be seen on a chest X-ray as a flattening of the diaphragm.[citation needed]

The most common cause of COPD is cigarette smoking. COPD is a gradually progressive condition and usually only develops after about 20 pack-years of smoking. COPD may also be caused by breathing in other particles and gases.[citation needed]

The diagnosis of COPD is established through spirometry although other pulmonary function tests can be helpful. A chest X-ray is often ordered to look for hyperinflation and rule out other lung conditions but the lung damage of COPD is not always visible on a chest x-ray. Emphysema, for example, can only be seen on CT scan.

The main form of long term management involves the use of inhaled bronchodilators (specifically beta agonists and anticholinergics) and inhaled corticosteroids. Many patients eventually require oxygen supplementation at home. In severe cases that are difficult to control, chronic treatment with oral corticosteroids may be necessary, although this is fraught with significant side effects.

COPD is generally irreversible although lung function can partially recover if the patient stops smoking. Smoking cessation is an essential aspect of treatment.[9] Pulmonary rehabilitation programmes involve intensive exercise training combined with education and are effective in improving shortness of breath. Severe emphysema has been treated with lung volume reduction surgery, with in carefully chosen cases. Lung transplantation is also performed for severe COPD in carefully chosen cases.[10]

Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency is a fairly rare genetic condition that results in COPD (particularly emphysema) due to a lack of the antitrypsin protein which protects the fragile alveolar walls from protease enzymes released by inflammatory processes.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

editDiagnosis of obstructive disease requires several factors depending on the exact disease being diagnosed. However one commonality between them is an FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.7, i.e. the inability to exhale 70% of their breath within one second.[11]

Following is an overview of the main obstructive lung diseases. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is mainly a combination of chronic bronchitis and emphysema, but may be more or less overlapping with all conditions.[12]

| Condition | Main site | Major changes | Causes | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic bronchitis | Bronchus | Hyperplasia and hypersecretion of mucous glands | Tobacco smoking and air pollutants | Productive cough |

| Bronchiolitis (subgroup of chronic bronchitis) |

Bronchiole | Inflammatory scarring and bronchiolitis obliterans | Tobacco smoking and air pollutants | Cough, dyspnea |

| Bronchiectasis | Bronchus | Dilation and scarring of airways | Persistent severe infections | Cough, purulent sputum and fever |

| Asthma | Bronchus |

|

Immunologic or idiopathic | Episodic wheezing, cough, and dyspnea |

| Unless else specified in boxes then reference is [12] | ||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Expert Panel Report 2. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1997. NIH publication 97-4051.

- ^ Restrepo RD (September 2007). "Inhaled adrenergics and anticholinergics in obstructive lung disease: do they enhance mucociliary clearance?" (PDF). Respir Care. 52 (9): 1159–73, discussion 1173–5. PMID 17716384. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ^ a b "GINA – the Global INitiative for Asthma". Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ "Asthma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 25 November 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "What Is Bronchiectasis?". NHLBI. June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ Kleinschmidt, Paul. "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Emphysema". Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ BTS COPD Consortium (2005). "Spirometry in practice – a practical guide to using spirometry in primary care". pp. 8–9. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "GOLD – the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease". Archived from the original on 2011-02-16. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ "What is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)?". Archived from the original on 2008-06-14. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Weinberger, Steven (2019). Principles of Pulmonary Medicine. Elsevier. p. 93. ISBN 9780323523714.

- ^ Vogelmeier, Claus F.; Criner, Gerard J.; Martinez, Fernando J.; Anzueto, Antonio; Barnes, Peter J.; Bourbeau, Jean; Celli, Bartolome R.; Chen, Rongchang; Decramer, Marc; Fabbri, Leonardo M.; Frith, Peter; Halpin, David M. G.; López Varela, M. Victorina; Nishimura, Masaharu; Roche, Nicolas (2017-03-01). "Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 195 (5): 557–582. doi:10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. hdl:10044/1/53433. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 28128970.

- ^ a b Table 13-2 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology: With STUDENT CONSULT Online Access. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1. 8th edition.