Cartersville is a city in and the county seat of Bartow County, Georgia, United States;[6] it is located within the northwest edge of the Atlanta metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 23,187.

Cartersville, Georgia | |

|---|---|

Cartersville City Hall | |

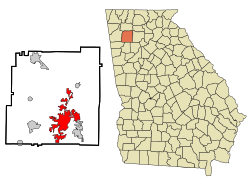

Location in Bartow County, Georgia | |

Location of Cartersville in Metro Atlanta | |

| Coordinates: 34°11′N 84°48′W / 34.183°N 84.800°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Bartow |

| Incorporated | 1850 |

| Named for | Farish Carter[1][2] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Matt Santini |

| Area | |

| • Total | 28.74 sq mi (74.44 km2) |

| • Land | 28.62 sq mi (74.12 km2) |

| • Water | 0.12 sq mi (0.32 km2) |

| Elevation | 787 ft (240 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 23,187 |

| • Density | 810.20/sq mi (312.82/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern Daylight Time) |

| ZIP Codes | 30120, 30121 |

| Area codes | |

| FIPS code | 13-13688[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0355017[5] |

| Website | cartersvillega.gov |

History

editCartersville, originally known as Birmingham, was founded by English-Americans in 1832.[7] The town was incorporated as Cartersville in 1854.[7] The present name is for Col. Farish Carter of Milledgeville, the owner of a large plantation.[8][9] Cartersville was the long-time home of Amos Akerman, U.S. Attorney General under President Ulysses S. Grant; in that office Akerman spearheaded the federal prosecution of members of the Ku Klux Klan and was one of the most important public servants of the Reconstruction era.[10]

Cartersville was designated the seat of Bartow County in 1867 following the destruction of Cassville by Sherman's March to the Sea in the American Civil War. Cartersville was incorporated as a city in 1872.[11]

On February 26, 1916, a group of 100 men and boys took Jesse McCorkle from the jail, hanged him from a tree in front of the city hall, and riddled his body with bullets.[12]

Geography

editCartersville is located in south-central Bartow County, 42 miles (68 km) northwest of downtown Atlanta and 76 miles (122 km) southeast of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The Etowah River flows through a broad valley south of the downtown, leading west to Rome, where it forms the Coosa River, a tributary of the Alabama River. The city limits extend eastward, upriver, as far as Allatoona Dam, which forms Lake Allatoona, a large U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reservoir. Red Top Mountain State Park sits on a peninsula in the lake, just outside the city limits. Nancy Creek also flows in the vicinity. The highest point in the city is 1,562 feet (476 m) at the summit of Pine Mountain.[13]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Cartersville has a total area of 29.3 square miles (75.9 km2), of which 29.2 square miles (75.5 km2) is land and 0.15 square miles (0.4 km2), or 0.59%, is water.[14]

Transportation

editInterstate 75, the major north-south route through the area, passes through the eastern edge of the city, with access from five exits: Exit 285 just south of the city limits in Emerson, Exit 288 (East Main Street) closest to downtown, and exits 290, 293, and 296 along the city's northern outskirts. U.S. Highway 41, which is concurrent with State Route 3, is an older, parallel highway to Interstate 75 that goes through the eastern edge of downtown, leading north to Calhoun and Dalton and south to Marietta. U.S. Highway 411 passes through the northern edge of the city, leading west to Rome and north to Chatsworth. State Route 20 runs west to Rome concurrent with U.S. Highway 411 and runs east to Canton. State Route 61 runs north to White concurrent with U.S. Highway 411 and runs south to Dallas, Georgia. State Route 113 runs southwesterly to Rockmart. State Route 293 runs west-northwest to Kingston.

Cartersville Airport is a public use airport located in the west side of Cartersville on State Route 61. It is the home base of Phoenix Air.

Cartersville area communities

editThe following communities border the city:

- Adairsville (north-northwest)

- Cassville (north)

- Emerson (south)

- Euharlee (west)

- Kingston (northwest)

- Stilesboro (southwest)

- White (northern)

- Grassdale Road (west)

Climate

edit| Climate data for Cartersville, Georgia (Cartersville Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1891–2019 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

83 (28) |

88 (31) |

93 (34) |

100 (38) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

108 (42) |

106 (41) |

100 (38) |

87 (31) |

82 (28) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.2 (20.1) |

73.0 (22.8) |

80.9 (27.2) |

85.7 (29.8) |

89.1 (31.7) |

93.9 (34.4) |

96.2 (35.7) |

95.5 (35.3) |

92.0 (33.3) |

84.7 (29.3) |

77.1 (25.1) |

69.0 (20.6) |

97.5 (36.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 52.2 (11.2) |

56.8 (13.8) |

64.9 (18.3) |

73.4 (23.0) |

80.7 (27.1) |

86.9 (30.5) |

89.6 (32.0) |

89.1 (31.7) |

84.2 (29.0) |

74.0 (23.3) |

62.9 (17.2) |

54.5 (12.5) |

72.4 (22.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 41.8 (5.4) |

45.5 (7.5) |

52.5 (11.4) |

60.2 (15.7) |

68.3 (20.2) |

75.6 (24.2) |

78.8 (26.0) |

78.1 (25.6) |

72.5 (22.5) |

61.6 (16.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

44.3 (6.8) |

60.8 (16.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 31.4 (−0.3) |

34.3 (1.3) |

40.2 (4.6) |

47.0 (8.3) |

56.0 (13.3) |

64.2 (17.9) |

68.0 (20.0) |

67.2 (19.6) |

60.7 (15.9) |

49.1 (9.5) |

38.7 (3.7) |

34.0 (1.1) |

49.2 (9.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 12.7 (−10.7) |

17.0 (−8.3) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

41.1 (5.1) |

52.5 (11.4) |

60.1 (15.6) |

59.5 (15.3) |

46.0 (7.8) |

32.7 (0.4) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

16.0 (−8.9) |

9.3 (−12.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −9 (−23) |

−6 (−21) |

8 (−13) |

22 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

40 (4) |

49 (9) |

48 (9) |

30 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

4 (−16) |

−3 (−19) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.29 (109) |

4.69 (119) |

4.72 (120) |

4.15 (105) |

3.67 (93) |

3.79 (96) |

3.88 (99) |

3.44 (87) |

3.63 (92) |

3.25 (83) |

4.06 (103) |

4.49 (114) |

48.06 (1,220) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.4 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.6 (1.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 10.7 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 131.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[15][16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service (mean maxima/minima 1981–2010)[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 2,232 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,037 | −8.7% | |

| 1890 | 3,171 | 55.7% | |

| 1900 | 3,135 | −1.1% | |

| 1910 | 4,067 | 29.7% | |

| 1920 | 4,350 | 7.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,250 | 20.7% | |

| 1940 | 6,141 | 17.0% | |

| 1950 | 7,270 | 18.4% | |

| 1960 | 8,668 | 19.2% | |

| 1970 | 10,138 | 17.0% | |

| 1980 | 9,247 | −8.8% | |

| 1990 | 12,035 | 30.2% | |

| 2000 | 15,925 | 32.3% | |

| 2010 | 19,731 | 23.9% | |

| 2020 | 23,187 | 17.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] 1850-1870[19] 1870-1880[20] 1890-1910[21] 1920-1930[22] 1940[23] 1950[24] 1960[25] 1970[26] 1980[27] 1990[28] 2000[29] 2010[30] 2020[31] | |||

Cartersville first appeared as a town in the 1870 U.S. Census.[19] The city absorbed the census-delineated neighboring unincorporated community of Atco prior to the 1960 U.S. Census.[24][25]

2020 census

edit| Race / ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop. 2000[32] | Pop. 2010[30] | Pop. 2020[31] | % 2000 | % 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 11,758 | 13,003 | 14,608 | 73.83% | 65.90% | 63.00% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 2,682 | 3,592 | 4,144 | 16.84% | 18.20% | 17.87% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 37 | 45 | 50 | 0.23% | 0.23% | 0.22% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 127 | 196 | 346 | 0.80% | 0.99% | 1.49% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 7 | 42 | 11 | 0.04% | 0.21% | 0.05% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 15 | 19 | 88 | 0.09% | 0.10% | 0.38% |

| Mixed race or multi-racial (NH) | 139 | 329 | 889 | 0.87% | 1.67% | 3.83% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,160 | 2,505 | 3,051 | 7.28% | 12.70% | 13.16% |

| Total | 15,925 | 19,731 | 23,187 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 23,187 people, 7,835 households, and 5,285 families residing in the city.

2010 census

editAs of the census[4] of 2010, there were 19,010 people, 5,870 households, and 4,132 families residing in the city. The population of Cartersville is growing significantly. The population density was 680.7 inhabitants per square mile (262.8/km2). There were 6,130 housing units at an average density of 262.0 per square mile (101.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 63.93% White, 29.64% African American, 0.82% Asian, 0.28% Native American, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 3.76% from other races, and 1.53% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 7.28% of the population.

There were 5,870 households, out of which 33.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.6% were married couples living together, 13.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.6% were non-families. 25.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.9% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 30.2% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $41,162, and the median income for a family was $48,219. Males had a median income of $35,092 versus $25,761 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,977. About 8.9% of families and 11.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.7% of those under age 18 and 15.4% of those age 65 or over.

Points of interest

edit- The Booth Western Art Museum is on North Museum Drive in Cartersville.[33] The Booth is the second-largest art museum in Georgia,[citation needed] and houses the largest permanent exhibition space for Western art in the country. It is a Smithsonian Institution Affiliate.

- The Etowah Indian Mounds is an archaeological Native American site in Bartow County, south of Cartersville.

- Tellus Science Museum, formerly the Weinman Mineral Museum, is a Smithsonian Institution Affiliate and features the first digital planetarium in North Georgia. NASA has installed a camera that tracks meteors at the museum.[34]

- The world's first outdoor Coca-Cola sign, painted in 1894, is located in downtown Cartersville on Young Brothers Pharmacy's wall.[35]

- Rose Lawn, a house museum, is the former home of noted evangelist Samuel Porter Jones,[36] for whom the Union Gospel Tabernacle (Ryman Auditorium) in Nashville was built, later to become the Grand Ole Opry.

- The Bartow History Museum is located in the Old Cartersville Courthouse, c. 1870, in downtown Cartersville on East Church Street.[37]

- Savoy Automobile Museum is a museum displaying a diverse collection of automobiles and original works of art.[38]

- The Pine Mountain Recreation Area trails ascend to a summit at 1562 feet overlooking Cartersville. Atlanta and Allatoona Lake can also be seen from the summit. The trails are maintained by City of Cartersville Parks & Recreation.

Education

editThe schools that comprise the Cartersville City School District are:

- Cartersville Primary School

- Cartersville Elementary School

- Cartersville Middle School

- Cartersville High School

There is also a private Montessori school:

- Lifesong Montessori School

Cartersville also has a college campus:

Economy

editManufacturing, tourism, and services play a part in the economy of the city. The city's employers include:

- Anheuser-Busch

- Georgia Power

- Komatsu

- Shaw Industries, a major flooring manufacturer

- Phoenix Air is based in the Cartersville Airport.

The city is home to Piedmont Cartersville Medical Center and the Hope Center, making it a minor healthcare hub for the surrounding area.[citation needed]

Law enforcement

editIn 2017, the Cartersville Police Department arrested 65 people at a house party because of a suspicion that there was an ounce of marijuana at the party. In 2022, a federal court awarded 45 of the arrested individuals a $900,000 settlement due to a violation of their constitutional rights.[39]

On September 8, 2022, Deputy Police Chief Jason DiPrima resigned after being arrested in a prostitute police-sting operation.[40][41]

Notable people

edit- Amos Akerman (February 23, 1821 – December 21, 1880), politician who served as United States Attorney General under President Ulysses S. Grant, 1870–1871

- Bill Arp (Charles Henry Smith; 1826–1903), nationally syndicated columnist[42]

- Robert Benham, first African-American Georgia Supreme Court justice

- Ronnie Brown, NFL running back

- Bob Burns (1950–2015), founding member and original drummer of Lynyrd Skynyrd

- Rebecca Latimer Felton (1835–1930), first female United States Senator

- Andre Fluellen, NFL defensive tackle

- W. J. Gordy, potter

- A. O. Granger (1846–1914), industrialist and founder of the Etowah Iron Company[43]

- Ashton Hagans, NBA point guard

- Corra Harris, author

- Joe Frank Harris (1936–), former governor of Georgia

- Keith Henderson, former NFL running back

- Sam Howard, professional baseball player for the Pittsburgh Pirates

- Samuel Porter Jones (1847–1906), evangelist

- Cledus T. Judd, country music singer

- Wayne Knight (1955–), actor

- Robert Lavette, professional football player

- Trevor Lawrence, quarterback at Cartersville High School (2014–2018), Clemson University (2018–2021) and the Jacksonville Jaguars

- Lottie Moon, Baptist missionary to China

- Chloë Grace Moretz, actress and model

- Donavan Tate, third overall pick in the 2009 Major League Baseball draft by the San Diego Padres

- Mark Thompson, NASCAR driver

- Benjamin Walker, actor

- Butch Walker (1969–), singer-songwriter and producer

- Hedy West (1938–2005), folk singer and songwriter

- Rudy York (1913–1970), professional baseball player

References

edit- ^ "Profile for Cartersvile, Georgia, GA". ePodunk. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ "City of Cartersville". State of Georgia. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Cartersville". Calhoun Times. September 1, 2004. p. 18. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 70.

- ^ Eric Foner (2014). "Reconstruction:America's Unfinished Revolution 1863 - 1877. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-235451-8.

- ^ Hellmann, Paul T. (May 13, 2013). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 223. ISBN 978-1135948597. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ Cincinnati Enquirer, Feb. 26, 1916

- ^ Pine Mountain Recreation Area. City of Cartersville. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Cartersville city, Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Cartersville AP, GA (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Cartersville, GA (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Atlanta". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decade". US Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "1870 Census of Population - Georgia - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1870.

- ^ "1880 Census of Population - Georgia - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1880.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1930.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1930. p. 251-256.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1940.

- ^ a b "1950 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1980.

- ^ a b "1960 Census of Population - Population of County Subdivisions - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1960.

- ^ "1970 Census of Population - Population of County Subdivisions - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1970.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1980.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population - Summary Social, Economic, and Housing Characteristics - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 1990.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - General Population Characteristics - Georgia" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 2000.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Cartersville, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Cartersville, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Cartersville, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ Lee Walburn (June 2005). Best Western — The Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville brings the old west to northwestern Georgia triggering celluloid-tinted memories of cowboys, standoffs, and frogs. Atlanta Magazine. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ Marie Nesmith. "NASA installs 'fireball' camera at Tellus Science Museum". The Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ Amy Gillis Lowry; Abbie Tucker Parks (May 1997). North Georgia's Dixie Highway. Arcadia Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7385-4431-1.

- ^ William Pencak (October 2009). Encyclopedia of the Veteran in America, Volume 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 615. ISBN 978-0-313-34009-3.

- ^ Matt Shinall. "Bartow History Museum reflects on past as transition into new home begins". The Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ "Savoy Auto Museum". Savoymuseum.org. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ Stevens, Alexis. "Police to pay 'Cartersville 70′ members $900K to settle federal lawsuit". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia Deputy Police Chief Nabbed in Florida for Solicitation". September 3, 2022.

- ^ "Busted: Deputy police chief shows up at Florida prostitution sting with White Claws, says Grady Judd". YouTube.

- ^ A book about the life of Bill Arp was written by another Cartersville resident: Parker, David B. (1991). Alias Bill Arp: Charles Henry Smith and the South's "Goodly Heritage". Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820313108.

- ^ Smith, Tony. "Overlook Scope". Lowndes County Historical Society Museum. Valdosta, Georgia. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

External links

edit- Official website

- Cartersville Archived May 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at New Georgia Encyclopedia

- The Daily Tribune, newspaper based in Cartersville

- News Talk AM 1270, radio station based in Cartersville