On 1 March 1815 Napoleon Bonaparte escaped from his imprisonment on the isle of Elba, and launched a bid to recover his empire. A confederation of European powers pledged to stop him. During the period known as the Hundred Days Napoleon chose to confront the armies of Prince Blücher and the Duke of Wellington in what has become known as the Waterloo Campaign. He was decisively defeated by the two allied armies at the Battle of Waterloo, which then marched on Paris forcing Napoleon to abdicate for the second time. However Russia, Austria and some of the minor German states also fielded armies against him and all of them also invaded France. Of these other armies the ones engaged in the largest campaigns and saw the most fighting were two Austrian armies: The Army of the Upper Rhine and the Army of Italy.

| Minor campaigns of 1815 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Seventh Coalition | |||||||

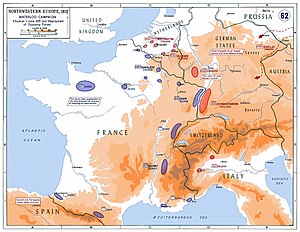

Strategic situation in Western Europe in June 1815 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Seventh Coalition: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

von Hake | ||||||

The Battle of Waterloo, followed as it was by the advance of the armies of Blücher and Wellington upon Paris, was so decisive in its effects, and so comprehensive in its results, that the great object of the War — the destruction of the power of Napoleon Bonaparte and the restoration of the Bourbon Dynasty under King Louis XVIII on 8 July 1815 — was attained while the armies of the Upper Rhine and of Italy were but commencing their invasion of the French territory. Had the successes attendant upon the exertions of Blücher and Wellington assumed a less decisive character, and, more especially, had reverses taken the place of those successes; the operations of the Armies advancing from the Rhine and across the Alps would have acquired an immense importance in the history of the war: but the brilliant course of events in the north of France materially diminished the interest excited by the military transactions in other parts of France. The operations of the Confederation armies which invaded France along her eastern and south eastern frontier; afford a clear proof that amongst the more immediate consequences of the decisive Battle of Waterloo and speedy capture of Paris, was their having been the means of averting the more general and protracted warfare which would probably have taken place on these frontiers, had a different result in Belgium emboldened the French to act with vigour and effect a stronger defence of these parts of France.[1]

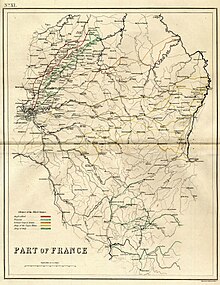

French deployments

editUpon assumption of the throne, Napoleon found that he was left with little by the Bourbons and that the state of the Army was 56,000 troops of which 46,000 were ready to campaign.[2] By the end of May the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment.[3]

By the end of May Napoleon had deployed his forces as follows:[4]

- I Corps (D'Erlon) cantoned between Lille and Valenciennes.

- II Corps (Reille) cantoned between Valenciennes and Avesnes.

- III Corps (Vandamme) cantoned around Rocroi.

- IV Corps (Gerard ) cantoned at Metz.

- VI Corps (Lobau) cantoned at Laon.

- Cavalry Reserve (Grouchy) cantoned at Guise.

- Imperial Guard (Mortier) at Paris.

The preceding corps were to be formed into L'Armée du Nord (the "Army of the North") and led by Napoleon Bonaparte would participate in the Waterloo Campaign. For the defence of France, Bonaparte deployed his remaining forces within France observing France's enemies, foreign and domestic, intending to delay the former and suppress the latter. By June they were organised as follows:

- V Corps – Armée du Rhin[5] (Rapp); cantoned near Strasbourg, with a strength of 46 guns[citation needed] and 20,000–23,000 men[6]

More troops guarded the south east frontier from Basel to Nice, and covered Lyons:

- VII Corps[7] – Armée des Alpes[8] (Suchet); based at Lyon, this army was charged with the defence of Lyon and to observe the Austro-Sardinian army of Frimont, with a strength of 42–46 guns[9] and 13,000–23,500 men[10]

- I Corps of Observation – Armée du Jura[8] (Lecourbe); based at Belfort, this army was to observe any Austrian movement through Switzerland and also observe the Swiss army of General Bachmann. Its composition in June was 38 guns,[7] and 5,392–8,400 men[11]

- II Corps of Observation – Armée du Var[12] (Brune): based at Toulon, with a strength of 10,000 men.

There were two other major deployments:

Upper Rhine frontier

editCoalition order of battle

editArmy of the Upper Rhine (Austo-German Army)

editThe Austrian military contingent was divided into three armies. This was the largest of these armies, commanded by Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg. Its target was Paris. This Austrian contingent was joined by those of the following nations of the German Confederation: Kingdom of Bavaria, Kingdom of Württemberg, Grand Duchy of Baden, Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt), Free City of Frankfurt, Principality of Reuss Elder Line and the Principality of Reuss Junior Line. Besides these there were contingents of Fulda and Isenburg. These were recruited by the Austrians from German territories that were in the process of losing their independence by being annexed to other countries at the Congress of Vienna. Finally, these were joined by the contingents of the Kingdom of Saxony, Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen and the Duchy of Saxe-Hildburghausen. Its composition in June was:[15]

| Corps | Commander | Men | Battalions | Squadrons | Batteries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Corps | Master General of the Ordnance, Count Colloredo | 24,400 | 86 | 16 | 8 |

| II Corps | General Prince Hohenzollern-Hechingen | 34,360 | 36 | 86 | 11 |

| III Corps | Field Marshal the Crown Prince of Württemberg | 43,814 | 44 | 32 | 9 |

| IV Corps (Bavarian Army) | Field Marshal Prince Wrede | 67,040 | 46 | 66 | 16 |

| Austrian Reserve Corps | General der Kavallerie Archduke Österreich-Este | 44,800 | 38 | 86 | 10 |

| Blockade Corps | 33,314 | 38 | 8 | 6 | |

| Saxon Corps | 16,774 | 18 | 10 | 6 | |

| Totals | 264,492[16] | 246 | 844 | 66 |

Swiss army

editThis army was composed entirely of Swiss. The Swiss General Niklaus Franz von Bachmann commanded this army. This force was to observe any French forces that operated near its borders. Its composition in July was:[17]

- I Division – Colonel von Gady

- II Division – Colonel Fuessly

- III Division – Colonel d'Affry

- Reserve Division – Colonel-Quartermaster Finsler

Total 37,000[18]

Planning

editAccording to the general plan of operations projected by Prince Schwarzenberg, this army was to cross the Rhine in two columns. The right column, consisting of the III Corps, under Field Marshal the Crown Prince of Württemberg; and of the IV Corps, of the Bavarian Army, under Field Marshal Prince Wrede, was to cross the Rhine between Germersheim and Mannheim. The Left Column, consisting of the I Corps, under the Master General of the Ordnance, Count Colloredo, and of the II Corps, under General Prince Hohenzollern-Hechingen together with the Austrian Reserve Corps; the whole being commanded by General the Archduke Ferdinand, was to cross the Rhine between Basel and Rheinfelden. The column formed by the right wing was to be supported by the Russian Army, under Field Marshal Count Barclay de Tolly, which was expected to be collected at Kaiserslautern by 1 July. The object of the operations, in the first instance, was the concentration of the Army of the Upper Rhine and the Russian Army at Nancy.[19]

Start of the campaign

editAs soon as Prince Schwarzenberg was made acquainted with the commencement of hostilities in what is now Belgium, he gave his orders for the advance of his Army. The IV (Bavarian) Corps was directed immediately to cross the Sarre: and, by turning through the Vosges Mountains, to cut off the French V Corps under General Rapp, collected in the environs of Strasbourg, from its base of operations; and to intercept its communications with the interior of France.[20]

A Russian Corps, under General Count Lambert, forming the advanced guard of the army of Count Barclay de Tolly, was attached to the IV (Bavarian) Corps of Prince Wrede; who was to employ it principally in keeping up the communication with the North German Corps under Prussian General von Hacke.[20][21]

Austrian right wing

editAustrian IV Corps

editOn 19 June, the Bavarian Army crossed the Rhine at Mannheim and Oppenheim, and advanced towards the Sarre river. On 20 June there were some minor skirmishes between advanced posts near Landau and Dahn. On 23 June, the Austrian army having approached the Sarre, proceeded, in two columns, to take possession of the passages across the river at Saarbrücken and Sarreguemines.[20]

The right column, under Lieutenant General Count Beckers, attacked Saarbrücken, where it was opposed by the French General Meriage. The Bavarians carried the suburb and the bridge, and penetrated into the town along with the retiring French; of whom they made four officers and seventy men prisoners, and killed and wounded one hundred men: suffering a loss, on their own part, of three officers and from fifty to sixty men killed and wounded. Count Beckers occupied the town, posted his division on the heights towards Forbach: and detached patrols along the road to Metz, as far as St. Avold; and to the right along the Sarre, as far as Saarlouis.[22]

The left column, consisting of the First Infantry Division, under Lieutenant General Baron von Ragliovich and of the First Cavalry Division, under Prince Charles of Bavaria, advanced against Sarreguemines; at which point the French had constructed a tête-de-pont on the right bank of the river. After some resistance, this was taken possession of by the Bavarians; whereupon Baron von Ragliovich marched through the town, and took up a position on the opposite Heights, commanding the roads leading to Bouquenom and Lunéville.[23]

The Fourth Infantry Division, under Lieutenant General Baron Zollern, advanced towards the Fortress of Bitche; which, however, the French commandant, General Kreutzer, refused to surrender.[23]

The Russian corps, under Count Lambert, attached to the right wing of Prince Wrede's Army, advanced as far as Ottweiler and Ramstein.[23]

Prince Wrede halts at Nancy

editOn 24 June, Prince Wrede occupied Bouquenom; and detached the cavalry division under Prince Charles towards Phalsbourg, to observe it. His second, third, and fourth divisions, and the reserve, were collected at Sarreguemines. The Russian troops under Count Lambert occupied Saarbrück, having previously detached the cavalry, under Lieutenant General Czernitscheff, as far as St. Avold.[23]

On 26 June, Prince Wrede Headquarters were at Morhenge; and, on 27 June, his advanced posts penetrated as far as Nancy, where he established his headquarters on 28 June. From St. Dieuze Wrede detached units to the left, in order to discover the march of General Rapp; who, however, was still on the Rhine, and whose retreat had thus become cut off by the occupation of Nancy.[24]

Prince Wrede halted at Nancy, to await the arrival of the Austrian and Russian corps. Upon his right Lieutenant General Czernitscheff crossed the Moselle, on 29 June, within sight of Metz; and carried by storm, on 3 July, the town of Châlons-sur-Marne. The garrison of this place had promised to make no resistance, and yet fired upon the Russian advanced guard; whereupon the cavalry immediately dismounted, scaled the ramparts, broke open the gates, sabred a part of the garrison, made the remainder prisoners, including the French General Rigault, and pillaged the town.[24]

After remaining four days in the vicinity of Nancy and Lunéville, Prince Wrede received an order from Prince Schwarzenberg to move at once upon Paris, with the IV (Bavarian) Corps; which was destined to become the advanced guard of the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine. This order was given in consequence of the desire expressed by the Duke of Wellington and Prince Blücher; that the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine should afford immediate support to their operations in front of Paris. On 5 July the main body of the Bavarian Army reached Châlons; in the vicinity of which it remained during 6 June. On this day, its advanced posts communicated, by Épernay, with the Prussian Army. On 7 July Prince Wrede received intelligence of the Convention of Paris, and at the same time, directions to move towards the Loire. On 8 July Lieutenant General Czernitscheff fell in with the French between Talus-Saint-Prix and Montmirail; and drove them across the Morin, towards the Seine. Previously to the arrival of the IV (Bavarian) Corps at Château-Thierry; the French garrison had abandoned the place, leaving behind it several pieces of artillery, with ammunition. On 10 July, the Bavarian Army took up a position between the Seine and the Marne; and Prince Wrede's Headquarters were at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre.[25]

Austrian III Corps

editOn 22 June, a portion of the Austrian III Corps, under the Crown Prince of Württemberg. took possession of the entrenchments of Germersheim, on the left bank of the Rhine. Lieutenant Field Marshal Count Wallmoden was posted, with ten battalions and four squadrons, to observe and blockade of the Fortress of Landau, and the Queich Line. The main body of the corps stood between Bruchsal and Philippsburg. On 23 June the corps crossed the Rhine at Germersheim, and passed the Line of the Queich without opposition.[26][27]

The Crown Prince was directed to proceed by Wissembourg and Haguenau with a view to complete, in conjunction with the IV (Bavarian) Corps, the plan of intercepting the retreat of General Rapp.[26]

On 24 June, the III Corps advanced to Bergzabern and Niederotterbach, engaged the French at both locations, and drove them back. Count Wallmoden left a small detachment to observe Landau, and advanced, with the remainder of his force, as far as Rheinzabern. On 25 June, the Crown Prince ordered the advance towards the Lines of Wissembourg, in two columns. The first column assembled at Bergzabern, and the second moved forward by Niederotterbach. Count Wallmoden was directed to advance upon Lauterburg. The Crown Prince advanced his Corps still further along the Haguenau road. His advanced guard pushed on to Ingolsheim, and the main body of the III Corps reached the Lines of Wissembourg; which the French abandoned in the night, and fell back upon the Forest of Haguenau, occupying the large village of Surbourg. On 26 June, the Crown Prince attacked and defeated the French at the last mentioned place, with his right column; whilst the left column, under Count Wallmoden, was equally successful in an attack which it made upon the French General Rothenburg, posted, with 6,000 infantry and a regiment of cavalry, at Seltz. On the following day, General Rapp fell back upon the Defile of Brumath; but this he quit in the night, and took up a favourable position in the rear of the Souffel, near Strasbourg. His force comprised twenty four battalions of infantry, four regiments of cavalry, and numerous artillery, and amounted to nearly 24,000 men.[28][29]

The Crown Prince of Württemberg engaged General Rapp's Army of the Rhine on 28 June at the Battle of La Suffel, but despite outnumbering the French two to one, the Austrian forces were repelled. Rapp, however, withdrew into the Fortress of Strasbourg shortly after the action, Austrian numbers telling. The loss of the III Corps on this occasion amounted to 75 officers, and 2,050 men, killed and wounded, while that of the French was about 3,000 men.[30]

Austrian left wing

editThe Austrian I and II corps and the Reserve Corps, forming the left wing of the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine, crossed this river at Rheinfelden and Basel in the night of 25 June. On 26 June the I Corps, under Count Colloredo, was directed upon Belfort and Montbéliard; and, on the same day, the Austrian invested the Fortress of Huningue. The advanced guard of the Austrian I Corps fought a skirmish with a French detachment of 3,000 men belonging to the VIII Corps (also known as Armée du Jura) of General Lecourbe, and forced it to withdraw as far as Dannemarie. On 28 June the Austrian I Corps attacked the French near Chavannes, between Dannemarie and Belfort, when the French force, amounting to 8,000 infantry and 500 cavalry, was driven back upon Belfort. Major General Von Scheither of the I Corps was detached against Montbéliard, a town fortified and defended by a citadel. After having maintained a most destructive fire against the place, the Austrian troops carried it by storm; with a loss however, of 25 officers and 1,000 men, killed and wounded.[8][31]

General suspension of hostilities

editThe III Corps remained in front of Strasbourg until 4 July when it was relieved by the arrival of the Austrian II Corps, under Prince Hohenzollern from the vicinity of Colmar. At this last point the advanced guard of the Austrian Reserve Corps, under Lieutenant Field Marshal Stutterheim, moved upon Remiremont, and the main body upon St. Marie aux Mines. The Austrian Reserve Corps itself reached Raon l'Etape; whence it subsequently moved (on 10 July) to Neufchâteau. The III Corps, under the Crown Prince of Württemberg, marched into the vicinity of Molsheim.[32]

On 7 July, Württemberg reached Lunéville, but instead of proceeding to its original destination of Nancy, on 9 July the III Corps took the road to Neufchâteau, advancing in columns; one via Bayon and the other via Rambervillers. These two columns continued their advance, the first by Vaucouleurs, Joinville, Brienne le Château, Troyes, and Auxerre; and the other, by Neufchâteau, Chaumont, Bar-sur-Aube, Vendeuvre-sur-Barse, Bar-sur-Seine, and Châtillon: at which points (Auxerre and Châtillon) they halted on 18 July. On 21 July, the corps entered into cantonments between Montbard and Tonnerre.[33]

With the exception of a few sorties of little consequence, General Rapp remained very quiet in the Fortress of Strasbourg. The news of the capture of Paris by the British and Prussian troops led to a Suspension of Hostilities which was concluded on 24 July and extended to the Fortress of Strasbourg, Landau, La Petite-Pierre, Huningue, Sélestat, Lichtenberg, Phalsbourg, Neuf-Brisach and Belfort.[34]

Italian frontier

editCoalition order of battle

editArmy of Upper Italy (Austro-Sardinian Army)

editThis was the second largest of Austria's contingents. Its target was Lyon. General Johann Maria Philipp Frimont commanded this army. Its composition in June was:[35]

- I Corps – Feldmarschall-Leutnant Paul von Radivojevich

- II Corps – Feldmarschall-Leutnant Ferdinand, Graf Bubna von Littitz

- Reserve Corps – Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz Mauroy de Merville

- Sardinian Corps – General Count Latour

Total 50,000.[18]

Austrian Army (Army of Naples)

editGeneral Bianchi commanded the Austrian Army of Naples.[a] This was the smaller of Austria's military contingents, and it had already defeated Murat's army in the Neapolitan War. Its objective in the current campaign was the capture of Marseilles and Toulon. It was not composed of Neapolitans as the army's name may suggest and as one author has supposed.[36] There was however a Sardinian force in this area forming the garrison of Nice under Lieutenant-General Giovanni Pietro Luigi Cacherano d'Osasco,[37] which may have been where this misunderstanding has arisen. The Army of Naples composition in June was:[38]

Total 23,000[18]

French order of battle

editThe French Army of the Var[18] (II Corps of Observation).[7]

Based at Toulon and commanded by Marshal Guillaume Marie Anne Brune. This army was charged with the suppression of any potential royalist uprisings and to observe Bianchi's 'Army of Naples'. Its composition in June was:

- 24th Infantry Division;[40]

- 25th Infantry Division;[40]

- 14th Chasseurs à Cheval Cavalry Regiment[41]

- 22 guns;[7]

Total 5,500–6,116 men.[42]

Start of the campaign

editThe Austrian Army of Italy, composed of Austrian and Sardinian troops, and amounting to 60,000 men, was under the command of General Baron Frimont. It was destined to act against the French Army of the Alps, under Marshal Suchet, posted in the vicinity of Chambéry and Grenoble. It is uncertain what size of force under Suchet, it having been estimated from 13,000 to 20,000 men; but the Corps of Observation on the Var, in the vicinity of Antibes and Toulon, under Marshal Brune, amounted to 10,000 and was not occupied with any Enemy in its front.[43]

Baron Frimont's' Army was divided into two Corps: the I Corps under Lieutenant Field Marshal Radivojevich, was to advance by the Valais towards Lyon; and the other, the II Corps under Lieutenant Field Marshal Count Bubna which was in Piedmont, was to penetrate into the south of France through Savoy.[43]

French abandon the passes of the Jura

editMarshal Suchet had received orders from Napoleon to commence operations on 14 June and by rapid marches to secure the mountain passes in the Valais and in Savoy (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), in order to close them to the Austrians. On 15 June, his troops advanced at all points for the purpose of gaining the frontier from Montmeilian as far as Geneva, which he invested. Thence he proposed to obtain possession of the important passes of Meillerie and St. Maurice and in this way to check the advance of the Austrian columns from the Valais. At Meillerie, the French were met and driven back by the advanced guard of the Austrian right column on 21 June. By means of forced marches the whole of this column, which Baron Frimont himself accompanied, reached the Arve on 27 June.[44] The left column, under Count Bubna, crossed Mount Cenis on 24 and 25 June. On 28 June, the column was sharply opposed by the French at Conflans; however, the Austrians succeeded in gaining possession of it.[45]

To secure the passage of the river Arve, on 27 June the advanced guard of the right column moved to Bonneville on its left bank but the French, who had already fortified this place, maintained a stout resistance. In the meantime however, the Austrians gained possession of the passage at Carrouge; by which means the French were placed under the necessity of evacuating Bonneville, and abandoning the valley of the Arve. The Austrian column now passed Geneva, and drove the French from the heights of Grand Saconex and from St. Genix. On 29 June, this part of the Austrian army moved towards the Jura and, on 1 July, it made its dispositions for attacking the redoubts and entrenchments which the French had thrown up to defend the passes. The most vigorous assault was made upon the Pass of Les Rousses, but the Austrians were driven back. Reserves were then brought up and the French, having quit their entrenchments to meet the latter, provided a good opportunity for a flank attack upon them with cavalry and artillery. The pass was captured by the Austrians and the French were compelled to abandon both it and the other passes of the Jura. The Austrian advance guard pursued the French and reached Saint-Claude in the evening, on the road leading to the left from Gex; and St. Laurent, in the original direction of the attack, beyond Les Rousses.[45]

Fort l'Ecluse surrendered to the Austrians

editIn the meantime, the Austrian Reserve Corps under Feldmarschalleutnant (Major-general) Meerville, was directed to advance and to throw back the French upon the Rhone. The latter, in retreating, destroyed the bridge of Seyselle and, by holding the Fort l'Ecluse, closed the road from Geneva to Lyon. A redoubt had been constructed in front of the fort which completely commanded the approach. It was stormed and carried by the Hungarian 'Fürst Esterhazy' Infantry Regiment (IR.32). The fort itself was now turned by the Reserve Corps along the left bank of the Rhône, with the design of forcing the passage at the Perte du Rhône. Here the French had constructed a tête-de-pont; which, however, they were forced to abandon in consequence of a movement made by the I Corps under Feldmarschalleutnant Radivojevich. On retiring, the French destroyed the very beautiful stone bridge then existing and thus rendered it necessary for the Austrians to construct temporary bridges over the extremely narrow space between the rocks which confine the stream at this remarkable spot. The advanced guard of the Reserve Corps, under General Count Hardegg, first crossed the Rhône and found the French posted at Charix, in rear of Châtillon, on the road to Nantua. Count Hardegg immediately ordered an attack and after encountering an obstinate resistance, forced the French to retire.[46]

The troops of the Austrian I Corps which, in the meantime, were left in front of the Fort l'Ecluse, had commenced a bombardment and this, after twenty-six hours duration, considerably damaged the fort. A powder magazine exploded, which caused a general conflagration; to escape which the garrison rushed out, and surrendered at discretion to the Austrians: thus, in three days, the high road from Geneva to Lyon was opened to the Army of Italy.[47]

Surrender of Lyon

editOn 3 July, General Bogdan, with the advanced guard of the Austrian I Corps, having been reinforced by Lieutenant Field Marshal Radivojevich, attacked the French at Oyonnax, beyond St. Claude, where the French General Maransin had taken up a favourable position with a force of 2,000 men. The Austrians turned Maransin's left flank, and forced the French to retire. The I Corps reached Bourg-en-Bresse on 9 July.[48]

On 10, July a detachment, under Major General von Pflüger, was pushed on to Mâcon on the Saône and gained possession of the tête-de-pont constructed there, and of the place itself.[49]

On 7 July, the II Corps, under Count Bubna, reached Echelles. A detachment, consisting principally of Sardinian troops under Lieutenant General Count Latour, had been directed to observe Grenoble, in front of which its advanced guard had arrived on 4 July. On 6 July the suburbs were attacked, and the communication between Grenoble and Lyon was cut off. The garrison, consisting of eight battalions of the National Guard, offered to capitulate on 9 July, on the condition of being permitted to return to their homes. That a vigorous defence might have been maintained was evident from the fact of the Austrians found in the place fifty four guns and eight mortars, and large quantities of provisions.[49]

Count Bubna's II Corps and the Reserve Corps, by simultaneous movements, assembled together in front of Lyon on 9 July. An armistice was solicited by the garrison on 11 July, and granted upon condition that Lyon and the entrenched camp should be evacuated and that the French VII Corps (Marshal Suchet's) retire behind the Loire, keeping Suchet's advanced posts within a stipulated line of demarcation.[49]

General armistice

editOn 9 July, the Sardinian Lieutenant-General d'Osasco, who had been detached to Nice, concluded an armistice with Marshal Brune, who commanded the Armée du Var, in front of the Maritime Alps.[50][b]

Having secured possession of the line of the Rhône as far down as its confluence with the Isère, and also of that part of the Saône between Mâcon and Lyon, the Army of Italy now proceeded towards the upper line of the latter river, leaving the II Corps under Count Bubna at Lyon, in front of Marshal Suchet. The I Corps marched upon Chalon-sur-Saône, in order to gain the tête-de-pont at that point. At this time, the French Armée du Jura under General Lecourbe was at Salins, between Dole and Pontarlier. As Besançon had not yet been invested, Baron Frimont detached a part of the Reserve Corps under General Hecht, to Salins, whilst General Folseis detached from the I Corps towards Dole. The advanced guard of the I Corps had arrived in front of the tête-de-pont at Châlons and had completed its dispositions for attack when the place surrendered. By the advance, at the same time, of Hecht upon Salina and of Folseist from Dole upon Besançon, the retreat of the French General Lapane was completely cut off. This led to a convention which stipulated the dissolution of the National Guard, the surrender of all the officers, and the abandonment of one of the forts of Salins to the Austrians.[51]

On 20 July, the I Corps advanced from Chalon-sur-Saône as far as Autun. Besançon having in the meantime been occupied by the Austrian troops of the Army of the Upper Rhine, a junction was effected with the latter by the Army of Italy by Dijon;[50] and thus terminated all hostilities on that side of France.[50]

Other campaigns

editThe Russians followed the northern wing of the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine into France and towards Paris while to its north the German Corps helped elements of the armies of Blücher and Wellington subdue some of the French frontier forts which did not immediately surrender to Coalition forces.

Russian army

editRussian order of battle

editField Marshal Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly commanded the First Russian Army. In June it consisted of the following:[52]

- III Army Corps – General Dokhturov

- IV Army Corps – General Raevsky

- V Army Corps – General Sacken

- VI Army Corps – General Langeron

- VII Army Corps – General Sabaneev[53]

- Reserve Grenadier Corps – General Yermolov

- II Reserve Cavalry Corps – General Wintzingerode

- Artillery Reserve – Colonel Bogoslavsky

Total 200,000[18]

Campaign

editThe main body of the First Russian Army, commanded by Field Marshal Count Barclay de Tolly and amounting to 167,950 men, crossed Germany rapidly in three main columns. The right column, commanded by General Doctorov, advanced by way of Kalisz, Torgau, Leipzig, Erfurt, Hanau, Frankfurt, and Hochheim am Main, towards Mainz. The central column, commanded by General Baron Sacken, advanced through Breslau, Dresden, Zwickau, Baireuth, Nuremberg, Aschaffenburg, Dieburg, and Gross Gerau, towards Oppenheim. The left column, commanded by General Count Langeron, proceeded through Prague, Aube, Adelsheim, Neckar, and Heidelberg, towards Mannheim. The vanguards of the columns had reached the Middle Rhine when hostilities were on the point of breaking out upon the Belgian frontier. The Russians crossed the Rhine at Mannheim, on 25 June and followed the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine. The greater portion of it reached Paris and its vicinity by the middle of July.[54]

German Corps

editThe German Corps (or the North German Federal Army) was part of the Prussian Army above, but was to act independently much further south. It was composed of contingents from the following nations of the German Confederation: Electorate of Hessen, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Duchy of Oldenburg (state), Duchy of Saxe-Gotha, Duchy of Anhalt-Bernburg, Duchy of Anhalt-Dessau, Duchy of Anhalt-Kothen, Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Principality of Waldeck (state), Principality of Lippe and the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe.[55]

Fearing that Napoleon was going to strike him first, Blücher ordered this army to march north to join the rest of his own army.[56] The Prussian General Friedrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf initially commanded this army before he fell ill on 18 June and was replaced temporarily by the Hessen-Kassel General von Engelhardt (who was in command of the Hessen division) and then by Lieutenant General Karl Georg Albrecht Ernst von Hake.[57][58] Its composition in June was:[59][60][c]

- Hessen-Kassel Division (Three Hessian infantry brigades, cavalry brigade and two artillery batteries), commanded by General Engelhardt

- Thuringian Brigade (12 battalions of infantry), commanded by Major General Egloffstein (Weimar)

Total 25,000[18]

The German Corps, which was composed of contingent forces supplied by the small principalities of north Germany was assembled, in the middle of April, in the vicinity of Koblenz. It amounted to 26,200 men, divided into thirty battalions of infantry, twelve squadrons of cavalry, and two and a half batteries of artillery and was placed under the command of General Count Kleist von Nollendorf. Later, it crossed the Rhine at Koblenz and Neuwied, and took up a position on the Moselle and the Sarre; its right communicating with the Prussian II Corps (Pirch I), and its Left with the Austrian IV (Bavarian) Corps (Prince Wrede) at Zweibrücken. Its advanced posts extended along the French frontier from Arlon to Mertzig. Its headquarters was at Trier, on the Moselle.[61]

It remained in this position until 16 June when its commander, General von Engelhard (in the absence of Count Kleist who was ill), advanced from Trier to Arlon which it reached on 19 June. Here it remained until 21 June, when it received an order from Prince Blücher to move into France by Bastogne and Neufchâteau and to gain possession of the fortresses of Sedan and Bouillon. On 22 June, the Corps commenced its march, in two columns: the first by Neufchâteau, toward Sedan, the other by Recogne, toward Bouillon. Sedan capitulated on 25 June after a few days' bombardment. An attempt was made to take Bouillon by a coup de main, but its garrison was strong enough to frustrate this project. The place was not considered of sufficient importance to render a regular siege expedient, and it was therefore simply invested from 25 June until 21 August,[62][63] when a battalion of the Netherlands Reserve Army under Lieutenant-general baron Tindal took over (Like the German Corps, the Netherlands Reserve Army did not take part in the early actions of the Waterloo Campaign[62][63]).[64]

On 28 June, Lieutenant General von Hacke, who had been appointed to the command of the German Corps, directed the advance guard to move upon Charleville, which lies under the guns of the Fortress of Mézières, and to carry the place by storm. The capture was successfully made by some Hessian battalions and tended greatly to facilitate the siege of Mézières. Mobile columns were detached to observe the Fortresses of Montmédy, Laon, and Rheims. The last named place was taken by capitulation on 8 July and the garrison, amounting to 4,000 men, retired behind the Loire.[45]

Lieutenant General von Hake finding that, notwithstanding his bombardment of Mézières which he commenced on 27 June, his summons to surrender was unheeded by the commandant, General Lemoine, undertook a regular siege of the place and opened trenches on 2 August. On 13 August the French garrison gave up the town and retired into the citadel, which surrendered on 1 September.[45]

The efforts of the German Corps were now directed upon the fortress of Montmédy, around which it had succeeded in placing twelve batteries in position by 13 September. After an obstinate resistance, the garrison concluded a convention on 20 September by which it was to retire, with arms and baggage, behind the Loire. After the capture of Montmédy, the German Corps went into cantonments in the department of the Ardennes whence it returned home in the month of November.[45]

British Mediterranean contingent

editThis was Great Britain's smaller military expedition. It was composed of British troops from the garrison of Genoa under General Sir Hudson Lowe. The troops were transported and supported by the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet commanded by Lord Exmouth. The British landed at Marseilles to support a French Royalist uprising that had expelled Marshal Brune's garrison. The British expeditionary force landed before Marshal Brune was able advance from Toulon with reinforcements from the Armée du Var. The National Guard of Marseilles, reinforced by 4,000 British soldiers, marines, and seamen marched out to meet this advance. Faced by this force Brune retrograded to Toulon and then surrendered the city to the Coalition forces.[65]

La Vendée

editArmy of the West,[7] – Armée de l'Ouest[18] (also known as the Army of the Vendée and the Army of the Loire) – originally formed as the Corps of Observation of the Vendée. This army was formed to suppress the Royalist revolt in the Vendée region of France which was up in revolt at Napoleon Bonaparte's return. It was commanded by General Jean Maximilien Lamarque.

The total planned strength was 10,000 to 12,000 men, but the highest estimate of total strength is 6,000 men.[66]

Provence and Brittany which were known to contain many royalist sympathisers did not rise in open revolt, but the La Vendée did. The Vendée Royalists successfully took Bressuire and Cholet before they were defeated by General Lamarque at the Battle of Rocheserviere on 20 June. They signed the Treaty of Cholet six days later on 26 June.[8][67][68]

Other mobilisations

editFor mobilisations that did not take an active part in operations, or were just planned mobilisations, see the article "Military mobilisation during the Hundred Days".

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Chandler names General Onasco as the commander of the Austrian Army of Naples (Chandler 1981, p. 30) however, both Plotho and Vaudoncourt name Bianchi as commander of this army (Plotho 1818, pp. 76, 77 (Appendix), and Vaudoncourt 1826, p. 94 (Book I, Chapter I))

- ^ David Chandler gives a slightly different account: Brune fell back slowly, before Neapolitan forces under the command of General d'Osasco, into the fortress city of Toulon and that Brune did not surrender the city and the naval arsenal contained within until 31 July (Chandler 1981, p. 181).

- ^ A third brigade, the Mecklenburg Brigade commanded by General Prince of Mecklenburg-Schwerin is included in Plotho, but not by Hofschröer & Embleton (Plotho 1818, p. 56; Hofschröer & Embleton 2014, p. 42).

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 764, 779, 780.

- ^ Chesney 1868, p. 34.

- ^ Chesney 1868, p. 35.

- ^ a b Beck 1911, p. 371.

- ^ Chandler 1981, p. 180.

- ^ Armée du Rhin men

- 20,000 (Beck 1911, p. 371)

- 20,4056 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- 23,000. (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- ^ a b c d e Chalfont 1979, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d Chandler 1981, p. 181.

- ^ Armée des Alpes guns

- 42 (Zins 2003, pp. 380–84)

- 46 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- ^ Armée des Alpes men

- 13,000–20,000 (Siborne 1895, p. 775)

- 23,500 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- 15,767 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- ^ Armée du Jura: men

- 5,392 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- 8,400 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 775, 779.

- ^ Beck 1911, p. 371 for commanders and the number of men.

- ^ Andersson 2009 for where the armies were cantoned.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 767.

- ^ Although Siborne estimated the number at 264,492, David Chandler estimated the number 232,000 (Chandler 1981, p. 27).

- ^ Chapuisat 1921, table 2.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g Chandler 1981, p. 30.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 767, 768.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1895, p. 768.

- ^ McGuigan 2009, § Siege Train.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 768, 769.

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1895, p. 769.

- ^ a b Siborne 1895, p. 770.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 770, 771.

- ^ a b Siborne 1895, p. 771.

- ^ The "line of the Queich" was of some age as it is also mentioned by Sir Edward Guest in "Wars of the Eighteenth Century Vol IV (1783–1795)" pub 1862, section "1793: Wars of the German Frontier", p. 158

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 771, 772.

- ^ Surburg www.clash-of-steel.co.uk [better source needed]

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 772.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 773, 774.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 772, 773.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 773.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 774.

- ^ Plotho 1818, pp. 74, 75 (Appendix).

- ^ Chandler 1981, p. 27.

- ^ Schom 1992, p. 19.

- ^ Plotho 1818, pp. 76, 77 (Appendix).

- ^ a b Pappas 2008.

- ^ a b Vaudoncourt 1826, Book I, Chapter I, p. 110.

- ^ Houssaye 2005, p. [page needed]

- ^ Army of the Var, men:

- 5,500 (Chandler 1981, p. 30)

- 6,116 (Chalfont 1979, p. 205)

- ^ a b Siborne 1895, p. 775.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 775, 776.

- ^ a b c d e Siborne 1895, p. 776.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 776, 777.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 777.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 777, 778.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1895, p. 778.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1895, p. 779.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 778, 779.

- ^ Plotho 1818, pp. pp. 56–62 (Appendix (chapter XII)).

- ^ Mikaberidze 2002.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 51, 52, 774.

- ^ Plotho 1818, p. 54.

- ^ Hofschröer 1999, p. 182.

- ^ Hofschröer 1999, pp. 179, 182.

- ^ Pierer 1857, p. 605, 2nd column.

- ^ Plotho 1818, Appendix (Chapter XII) p. 56.

- ^ Hofschröer & Embleton 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 765.

- ^ a b Siborne 1895, pp. 765, 766.

- ^ a b McGuigan 2009, § Netherlands Corps.

- ^ Anonymous 1838, p. [page needed].

- ^ Parkinson 1934, pp. 416–418.

- ^ Muret, p. 435.

- ^ Gildea 2008, pp. 112, 113.

- ^ Philp & Hambridge 2015.

References

edit- Andersson, M. (2009). "100 Days: § Napoleon's reaction". Napoleonic Wars website. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2011. [better source needed]

- Anonymous (1838). Geschichte des Feldzugs von 1815 in den Niederlanden und Frankreich als Beitrag zur Kriegsgeschichte der neuern Kriege. […] Part II (in German). Berlin, Posen and Bromberg: Ernst Siegfried Mittler.

- Barbero, Alessandro (2006). The Battle: a new history of Waterloo. Walker & Company. ISBN 0-8027-1453-6.

- Beck, Archibald Frank (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 371–381.

- Chalfont, Arthur Gwynne Jones, ed. (1979). Waterloo: Battle of Three Armies. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. ISBN 0-2839-8235-7.

- Chandler, David (1981) [1980]. Waterloo: The Hundred Days. Osprey Publishing.

- Chapuisat, Édouard (1921). Der Weg zur Neutralität und Unabhängigkeit 1814 und 1815 (in German). Bern: Oberkriegskommissariat.

- Chesney, Charles Cornwallis (1868). Waterloo lectures: a study of the campaign of 1815. London: Longmans Green and Company.

- Gildea, Robert (2008). Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799–1914 (reprint ed.). Penguin UK. pp. 112, 113. ISBN 978-0-14-191852-5.

- Glover, Michael (1973). Wellington as Military Commander. London: Sphere Books.

- Parkinson, C. (1934). "CHAPTER XII - Algiers". Edward Pellew. London: Northcote. pp. 416–418.

- Gurwood, ed. (1838). The Dispatches of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. Vol. 12. London: John Murray.

- Hofschröer, Peter (2006). 1815 The Waterloo Campaign: Wellington, his German Allies and the Battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras. Vol. 1. London: Greenhill Books.

- Hofschröer, Peter (1999). 1815: The Waterloo Campaign: The German victory, from Waterloo to the fall of Napoleon. Vol. 2. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-368-4.

- Hofschröer, Peter; Embleton, Gerry (2014). The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815. Osprey Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-78200-619-0.

- Houssaye, Henri (2005). Napoleon and the Campaign of 1815: Waterloo. Naval & Military Press.

- McGuigan, Ron (2009) [2001]. "Anglo-Allied Army in Flanders and France – 1815: Subsequent Changes in Command and Organization". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 31 May 2012. [better source needed]

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2002). "Russian Generals of the Napoleonic Wars: General Ivan Vasilievich Sabaneev". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 31 May 2012. [better source needed]

- Pappas, Dale (July 2008). "Joachim Murat and the Kingdom of Naples: 1808 – 1815". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 31 May 2012.[better source needed]

- Philp, Mark; Hambridge, Katherine; et al. (2015). "The Treaty of Cholet and the Pacification of the Vendée". University of Warwick online exhibition.

- Pierer, H.A. (1857). "Russisch-Deutscher Krieg gegen Frankreich 1812-1815". Pierer's Universal-Lexikon (in German). Vol. 14. p. 605, 2nd column.

- Plotho, Carl von (1818). Der Krieg des verbündeten Europa gegen Frankreich im Jahre 1815 (in German). Berlin: Bei Karl Friedrich Umelang.

- Raa, F.J.G. ten (1980) [1900]. De uniformen van de Nederlandsche zee—en landmacht hier te lande en in de kolonien... (in Dutch). Historical Section of the Royal Netherlands Army. OCLC 768909746. OL 3849493M.

- Schom, Alan (1992). One Hundred Days: Napoleon's Road to Waterloo. New York: Atheneum.

- Sørensen, Carl (1871). Kampen om Norge i Aarene 1813 og 1814 (Battle for Norway in the years 1813 and 1814) (in Danish). Vol. 2. Copenhagen.

- Vaudoncourt, Guillaume de (1826). Histoire des Campagnes de 1814 et 1815 en France (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: A. de Gastel.

- Wellesley, Arthur, ed. (1862). Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. United Services. Vol. 10. London: John Murray.

- Zins, Ronald (2003). 1815: L'armée des Alpes et Les Cent-Jours à Lyon. Reyrieux: H. Cardon.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Siborne, William (1895). "Supplement section". The Waterloo Campaign 1815 (4th ed.). Birmingham, 34 Wheeleys Road. pp. 767–780.

Further reading

edit- Labarre de Raillicourt, Dominique (1963). Les généraux des Cents jours et du gouvernement provisoire (mars-juillet 1815) Dictionnaire biographique, promotions, bibliographies et armorial (in French). Paris: Chez l'auteur.

- Six, Georges (1934). Dictionnaire biographique des généraux & amiraux Français de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1792–1814) (Two volumes) (in French). Paris, Librairie Saffroy.