Ormond-by-the-Sea is a census-designated place and an unincorporated town in Volusia County, Florida, United States. The population was 7,312 as of the 2020 census, a decrease from 7,406 in the 2010 census.[4]

Ormond-by-the-Sea, Florida | |

|---|---|

Skyline of Ormond-by-the-Sea | |

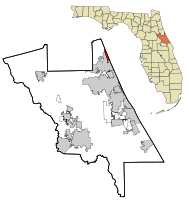

Location in Volusia County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 29°20′21″N 81°3′57″W / 29.33917°N 81.06583°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Volusia |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.02 sq mi (5.23 km2) |

| • Land | 2.02 sq mi (5.22 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 7,312 |

| • Density | 3,626.98/sq mi (1,400.49/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| FIPS code | 12-53200[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0288246[3] |

Geography

editOrmond-by-the-Sea is located at 29°20′21″N 81°3′57″W / 29.33917°N 81.06583°W (29.339206, -81.065756).[5]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 5.2 km2 (2.0 sq mi), of which 5.2 km2 (2.0 sq mi) is land and 0.50% is water.

The boundaries of Ormond-by-the-Sea include the Volusia/Flagler county line on the north, the city of Ormond Beach on the south, the Atlantic Ocean on the east, and the Halifax River on the west. The area has traditionally been called the North Peninsula, although other nicknames such as OBC or OBTS are sometimes used.

There are two principal roads, State Road A1A (also known as Ocean Shore Boulevard), which runs along the Atlantic Ocean, and John Anderson Drive, which runs along the Halifax River.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 8,430 | — | |

| 2010 | 7,406 | −12.1% | |

| 2020 | 7,312 | −1.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[6][4] | |||

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 8,430 people, 4,296 households, and 2,495 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 1,635.6 people/km2 (4,236 people/sq mi). There were 5,689 housing units at an average density of 1,103.8 units/km2 (2,859 units/sq mi). The racial makeup of the CDP was 97.53% White, 0.33% African American, 0.39% Native American, 0.50% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.28% from other races, and 0.87% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.30% of the population.

There were 4,296 households, out of which 13.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.4% were married couples living together, 8.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.9% were non-traditional families. 35.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 20.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.96 and the average family size was 2.46.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 12.9% under the age of 18, 3.8% from 18 to 24, 20.2% from 25 to 44, 27.6% from 45 to 64, and 35.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 54 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.4 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $34,970, and the median income for a family was $38,731. Males had a median income of $27,536 versus $25,357 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $22,503. About 7.3% of families and 9.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.2% of those under age 18 and 6.7% of those age 65 or over.

History and local landmarks

editThe earliest known inhabitants of the Ormond-by-the-Sea area were the Timucuan Indians, who in the sixteenth century occupied a large village called Nocoroco, located at the site of Tomoka State Park. The Timucuan diet relied heavily on oysters and other shellfish, and their shell middens, or trash heaps, may still be found near the Halifax River in Ormond-by-the-Sea.

Among the first Anglo settlers of the area was Chauncey A. Bacon, an architect and Civil War veteran from New Britain, Connecticut, who in 1876 purchased 172 acres (0.70 km2) in present-day Ormond-by-the-Sea and named it the Number Nine Plantation. In her book Ormond-On-The-Halifax, Alice Strickland describes the site: "The land was covered with a dense, tangled forest of palmettos, scrub oaks, and pine trees which Bacon cleared out with axe and grub hoe. The Bacon's first home was a palmetto cabin, but later Bacon built a small, two story house with a large coquina rock fireplace on top of the Indian shell mound."

The Bacons later constructed a larger home, which still stands on John Anderson Drive, from salvaged mahogany logs that washed ashore from the City of Vera Cruz shipwreck. The property was also planted with a large fruit grove featuring oranges, grapefruit, lemons, loquats and guavas, among others. By the turn of the century, the Bacons had a thriving home business selling brandied figs and their best-selling "Number 9 Guava Jelly."

In 1909, the Bacons sold Number Nine Plantation to M.C. Hillery who operated it for a few years and then sold it in 1911 to a company that had been organized by Ferdinand Nordman Jr. Nordman constructed a "jelly house" and enlarged the fruit business, selling fruit preserves via mail order to customers across the country, including New York Governor, Nelson Rockefeller. The business survived until 1968, and the jelly house was demolished to make way for a subdivision in 1984.[7]

Another early settler was Leonard B. Knox, who developed a citrus plantation known as Mound Grove, located along High Bridge Road near its crossing with Bulow Creek. It was Knox's son Donald who planted the Canary Island date palms which currently line the road. Part of the property also included a waterside building that operated as Uncle Guy's Fish Camp between the 1930s and 1950s. The property was subsequently acquired by Dick Cobb, who operated a bar and restaurant out of the building, which became known as "Cobb's Corner." The business closed in the 1970s, although portions of the structure remain.[8]

Despite these early settlements, nearly all of present-day Ormond-by-the-Sea remained undeveloped until the 1950s, when the area began to develop in earnest as a retirement community. The "by the sea" appellation was used to distinguish the area from the adjacent city of Ormond Beach, located immediately to the south. Though unincorporated, it was first represented by the North Peninsula Zoning Commission, created in 1955.[9]

For many years, one of Ormond-by-the-Sea's most distinguishing landmarks was the Ormond Pier, a 750-foot (230 m) steel structure constructed in 1959 near the intersection of Laurie Drive and A1A.[10] A large section of the Ormond Pier was torn away by a storm in November 1984, and the remaining portions subsequently demolished for safety reasons in the early 1990s.[11]

Approximately one mile north on A1A, near the intersection of A1A and Spanish Waters Drive, stands a watch tower constructed in 1942 by the Coast Guard Reserve to look out for German U-boats operating off the coast.[12] The tower was restored in 2004 and is one of the last remaining examples of a World War II era observation tower on the Florida coast.

At the northern end of Ormond-by-the-Sea is the North Peninsula State Park, comprising approximately 800 acres (3.2 km2) of undeveloped coastal dunes and marsh lands, which were acquired in the mid-1980s through the Conservation & Recreation Lands Program,[13] later known as the "Preservation 2000" and "Florida Forever" programs. Among other species, the park provides crucial habitat for the Florida scrub jay, a threatened federal species of which less than 4,000 breeding pairs are thought to survive.

Ecology

editThough most of Ormond-by-the-Sea is little more than a half-mile wide, it supports no fewer than six distinct ecological zones. The beach, or tidal zone, features distinctive reddish-colored sand created by crushed coquina shells. Here may be found sand fleas and ghost crabs, as well as a variety of coastal birds including plovers, stilts, avocets, terns, and gulls. Just above the tide line, several species of sea turtles are known to lay their eggs, including the leatherback, Atlantic loggerhead, and green turtle.

Immediately inland is the Temperate Beach Dune, a "pioneer zone" of vegetation growing along the primary dunes. Species of note include sea oats, beach morning glory, and beach sunflower.

Slightly inland from the primary dunes is the Coastal Strand, a shrubby area dominated by saw palmetto, Spanish bayonet, prickly pear cactus, and greenbrier vines. The Coastal Strand frequently overlaps with nearby sand ridges featuring Florida scrub plant communities, including scrub live oaks, slash pine, and Florida's state tree, the sabal palm (often called a "cabbage palm"). Species of note include the Florida scrub jay and the endangered gopher tortoise.

Close to the Halifax River, the soil is more moist and supports Maritime Hammock species, including live oaks, magnolias, American holly, red cedars and coontie ferns. In many areas, Brazilian pepper trees, an invasive exotic species, may also be seen growing.

The river's edge features many plants associated with tidal marshes, including salt marsh cordgrass, needle rush and mangroves. Oysters and blue crabs are common in the shallow waters, as are a variety of wading birds including egrets and herons.

References

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b United States Census Bureau, 2020 Census Results, QuickFacts, Ormond-by-the-Sea, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ormondbytheseacdpflorida, accessed: November 30, 2023

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "Landmark Makes Way for Housing Tract" Daytona Beach News Journal July 8, 1984.

- ^ "Cobb's Corner" Daytona Beach News Journal September 8, 1976.

- ^ "Four Candidates Tell Whey They're Running for Commission Posts" Daytona Beach News Journal July 28, 1955.

- ^ "Ormond Pier Construction on Schedule" Daytona Beach News Journal June 3, 1959.

- ^ "DEBATE EBBS AND FLOWS OVER ORMOND PIER". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ "Lonely Sentry on the North Peninsula" Daytona Beach News Journal October 1, 1975.

- ^ "Port Panel Takes Role for Acquiring N. Peninsula Tract" Daytona Beach News Journal August 25, 1982.