Sleepy Hollow is a village in the town of Mount Pleasant in Westchester County, New York, United States.

Sleepy Hollow, New York | |

|---|---|

The Old Dutch Church in 1907 | |

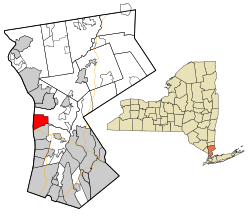

Location of Sleepy Hollow, New York | |

| Coordinates: 41°5′31″N 73°51′52″W / 41.09194°N 73.86444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Westchester |

| Town | Mount Pleasant |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.21 sq mi (13.48 km2) |

| • Land | 2.24 sq mi (5.81 km2) |

| • Water | 2.96 sq mi (7.67 km2) |

| Elevation | 89 ft (27 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 9,986 |

| • Density | 4,452.07/sq mi (1,718.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 10591 |

| Area code | 914 |

| FIPS code | 36-67638 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0958934 |

| Website | www |

The village is located on the east bank of the Hudson River, about 20 miles (32 km) north of New York City, and is served by the Philipse Manor stop on the Metro-North Hudson Line. To the south of Sleepy Hollow is the village of Tarrytown, and to the north and east are unincorporated parts of Mount Pleasant. The population of the village at the 2020 census was 9,986.[2]

Originally incorporated as North Tarrytown in the late 19th century (over two centuries after the original Dutch settlers arrived and called it "Slapershaven" or "Sleepers' Haven") as a way to draft off Tarrytown's success during the Industrial Revolution, the village adopted its current name in 1996.[3] The village is known internationally through "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow", an 1820 short story about the local area and its infamous specter, the Headless Horseman, written by Washington Irving, who lived in Tarrytown and is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, where in addition to Irving, numerous other notable people are buried. Owing to "The Legend", as well as the village's roots in early American history and folklore, Sleepy Hollow is considered by some to be one of the "most haunted places in the world".[4][5][6] Despite this designation, Sleepy Hollow has also been called "one of the safest places to live in the United States".[7]

History

editThe two square miles of land that would become Sleepy Hollow was originally occupied by the Weckquaesgeck Indians (a Delaware Tribe or Mohican Tribe).[8] In 1609, Henry Hudson claimed the Hudson Valley (known then as the Tappan Zee) for Holland.[9] There was relative peace between the Native Americans and Dutch until the mid-seventeenth century. The land was then bought from Adriaen van der Donck, a patroon in New Netherland before the English takeover in 1664. Starting in 1672, Frederick Philipse began acquiring large parcels of land mainly in today's southern Westchester County. Comprising some 52,000 acres (81 sq mi) of land, it was bounded by the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, the Croton River, the Hudson River, and the Bronx River. Philipse was granted a royal charter in 1693, creating the Manor of Philipsburg and establishing him as first lord.[10]

In today's Sleepy Hollow, he established an upper mill and shipping depot, today part of the Philipse Manor House historic site. A pious man, he was architect and financier of the town's Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow, and was said to have built the pulpit with his own hands.[11]

When Philipse died in 1702, the manor was divided between his son, Adolphus Philipse, and his grandson, Frederick Philipse II. Adolph received the Upper Mills property, which extended from Dobbs Ferry to the Croton River. Frederick II was given the Lower Mills at the confluence of the Saw Mill and Hudson Rivers, the two parcels being reunited on his uncle's death. His son, Frederick Philipse III, became the third lord of the manor in 1751.[10]

In 1779, Frederick III, a Loyalist, was attainted for treason. The manor was confiscated and sold at public auction, split between 287 buyers. The largest tract of land (about 750 acres (300 ha)) was at the Upper Mills; it passed to numerous owners until 1951, when it was acquired by Sleepy Hollow Restorations. Thanks to the philanthropy of John D. Rockefeller Jr., about 20 acres (8.1 ha) were restored as today's historic site.[10]

In the late 1790s, Washington Irving visited Sleepy Hollow with his friend James K. Paulding, a local militiaman that in 1780 had previously helped capture British Major John Andre in what is now known as Patriots Park and thereby foiled the plans of Benedict Arnold during the American Revolutionary War.[12] Together they explored the area, hunting, fishing and talking with the local folk. The visits of Irving - and the local folklore and ghost tales he heard while there - were immortalised in the story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow".

Geography

editSleepy Hollow is located at 41°5′31″N 73°51′52″W / 41.09194°N 73.86444°W (41.091998, −73.864361).[13] According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 5.1 square miles (13 km2), of which 2.3 square miles (6.0 km2) is land and 2.8 square miles (7.3 km2), or 55.58%, is water.[14]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,684 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,179 | 18.4% | |

| 1900 | 4,241 | 33.4% | |

| 1910 | 5,421 | 27.8% | |

| 1920 | 5,927 | 9.3% | |

| 1930 | 7,417 | 25.1% | |

| 1940 | 8,804 | 18.7% | |

| 1950 | 8,740 | −0.7% | |

| 1960 | 8,818 | 0.9% | |

| 1970 | 8,334 | −5.5% | |

| 1980 | 7,994 | −4.1% | |

| 1990 | 8,152 | 2.0% | |

| 2000 | 9,212 | 13.0% | |

| 2010 | 9,870 | 7.1% | |

| 2020 | 9,986 | 1.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] | |||

As of the census[16] of 2010, there were 9,870 people, 3,181 households, and 2,239 families residing in the village. The population density was 4,054.7 people per square mile (1,565.5 people/km2). There were 3,253 housing units at an average density of 1,431.8 per square mile (552.8/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 61.0% White, 6.2% African American, 0.8% Native American, 3.3% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander, 23.5% from other races, and 5.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 51.0% of the population, many of whom are Ecuadorian, Dominican, Chilean, and Puerto Rican. Sleepy Hollow has one of the highest proportions of Ecuadorian American residents of any community nationwide, standing at 17.5% as of the 2010 census.

There were 3,181 households, out of which 36.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.5% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.6% were non-families. 23.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.89 and the average family size was 3.37.

In the village, the population was spread out, with 25.0% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 36.7% from 25 to 44, 18.9% from 45 to 64, and 10.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.9 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $54,201, and the median income for a family was $63,889. Males had a median income of $39,923 versus $32,146 for females. The per capita income for the village was $28,325. About 5.7% of families and 7.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.3% of those under age 18 and 7.9% of those age 65 or over.

Notable landmarks

editThe village is home to the aforementioned Philipsburg Manor House, the Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow, and Patriots Park, all listed as National Historic Landmarks. Local sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places are the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery; the Edward Harden Mansion, now serving as the administration building for the Public Schools of the Tarrytowns; the Philipse Manor Railroad Station, now repurposed by the Hudson Valley Writers Center; the Tarrytown Light; and the Old Croton Aqueduct, segments of which run through Sleepy Hollow. Also of note are Kingsland Point Park, allegedly haunted by the spirit of Captain Kidd, an associate of Philipse; Philipse Manor Beach Club; Sleepy Hollow Manor, residential neighborhood on the former estate of renowned explorer and politician John C. Frémont, whose now-updated house still overlooks the Hudson River there; and the Rockefeller State Park Preserve.

Emergency services

editAs of 2014[update], the village's police department had 27 officers, four school crossing guards, and three civilian employees.[17] The village is also served by the New York State Police and Westchester County Department of Public Safety.[18] Police officers from the villages of Sleepy Hollow and Dobbs Ferry, the town of Greenburgh, and the New York State Police make up a Marine / H.E.A.T. Unit.[19] As of 2006, police base salaries in Sleepy Hollow were low compared to other Westchester County forces, in part due to the lower tax base.[20]

The Sleepy Hollow Fire Department began with organization of the North Tarrytown Fire Patrol on May 26, 1876. Within 25 years it had grown to five companies in three fire stations. As of 2019, there were three engines, one tower ladder, one rescue, and other equipment. The fire department is run by volunteers and responds to over 300 calls each year. The local hospital, Phelps Memorial, responds to hundreds of emergencies per year.[21]

Emergency medical services in Sleepy Hollow depend on volunteers assisted by paid staff. The Ambulance Corps has two basic life support ambulances. Mount Pleasant Paramedics provides advanced life support.[22]

Education

editMost of Sleepy Hollow is in Union Free School District of the Tarrytowns while a portion is in Pocantico Hills Central School District.[23]

In popular culture

editSleepy Hollow has been used as a setting or filming location for numerous media works, including films, games, literature, motion pictures, and television productions, including:

- Literature

- Sleepy Hollow is the setting of Washington Irving's short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820), its many adaptations in other media, and its major characters, Ichabod Crane and The Headless Horseman.

- Films

- The Curse of the Cat People (1944)

- The second segment of Walt Disney's The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949)

- The Scarlet Coat (1955), partially about American Revolutionary War general Benedict Arnold's associate John Andre's pivotal real-life capture in the village

- the adaptation of the Dark Shadows television series, House of Dark Shadows (1970)

- Woody Allen's Mighty Aphrodite (1995)

- Sidney Lumet's Gloria remake (1999)

- The Thomas Crown Affair remake (1999)

- Tim Burton's Sleepy Hollow (1999), shot primarily in England

- The Family Man (2000)

- Super Troopers (2001)

- Lord of War (2005)

- Robert De Niro's The Good Shepherd (2006)

- Why Stop Now (2012)

- The English Teacher (2013)

- the Stephen King adaptation A Good Marriage (2014)[24]

- the adaptation of The Girl on the Train (2016)

- The Meyerowitz Stories (2017), filmed primarily in and around Northwell Health's Phelps Memorial Hospital Center

- Wonderstruck (2017)

- The Netflix Halloween film The Curse of Bridge Hollow (2022), which substitutes the Headless Horseman legend with the lore of Stingy Jack in a thinly-veiled contemporary Sleepy Hollow, references the “safest small city in America” distinction.

- Games

- One of the locations in Magicland Dizzy is named after the village (1990).

- Sleepy Hollow is a location in the game Assassin's Creed Rogue (2014).

- Television

- The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1980), TV movie starring Jeff Goldblum, Paul Sand, and Meg Foster.

- The four-season Fox series Sleepy Hollow, though set in and around the village through the centuries, greatly expanded its population to 144,000, as indicated by a sign at the beginning of the pilot episode. Most of the series was filmed in North Carolina and Georgia, though several aerial shots of the actual village and surrounding region are incorporated into the series.

- Television personality and retired Olympic decathlete Caitlyn Jenner, who attended Sleepy Hollow High School, led TV journalist Diane Sawyer on a tour of the village and neighboring Tarrytown during her landmark coming-out interview on 20/20 in 2015.

Television shot on location in Sleepy Hollow includes:

- the "Tale of the Midnight Ride" episode of the Nickelodeon series Are You Afraid of the Dark?

- an episode of the HGTV series Property Brothers during its Westchester-dedicated season

- the HBO series Divorce starring Sarah Jessica Parker

- the "Two Boats and a Helicopter" episode of the HBO series The Leftovers

- the Amazon Prime Video series Sneaky Pete

- the Hulu series The Path

- an episode of the Travel Channel/Food Channel series Man v. Food[25]

- the Showtime miniseries Escape at Dannemora

- the FX series Pose

- the Netflix revival of the series Tales of the City

- an episode of the CBS series The Blacklist

- an episode of the AMC series TURN: Washington’s Spies

- the Netflix series Zero Day starring Robert De Niro

Notable people

editThis article's list of residents may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (April 2024) |

- Wolfert Acker (1667–1753), colonial-period American featured in Washington Irving's short story collection Wolfert's Roost and Miscellanies (1855)

- Bob Akin (1936–2002), business executive, journalist, television commentator and champion sports car racing driver

- Fay Baker (1917–1987), actress and author

- Kathleen Beller, actress

- David Bromberg, string instrumentalist, vocalist, and band leader

- Ana Cabrera, television journalist

- Clarence Clough Buel (1850–1933), editor and author

- Keith Hamilton Cobb, actor best known for The Young and the Restless

- Sam Coffey, professional soccer player for the Portland Thorns and the United States Women's National Team

- Abraham de Revier Sr. (c. 1650–c. 1720), early American historian and elder of the Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow

- Vincent Desiderio, realist painter

- Karen Finley, performance artist

- John C. Frémont (1813–1890), military officer, explorer, and politician who became the first candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party for the office of President of the United States

- Margaret Hardenbroeck (c. 1637–c. 1690), merchant in colonial New York and wife of Frederick Philipse

- Elsie Janis (1889–1956), singer, songwriter, actress, and screenwriter

- Mondaire Jones, former U.S. Representative of NY-17

- Tom Keene (1896–1963), actor best known for King Vidor's film classic Our Daily Bread and Ed Wood's film Plan 9 from Outer Space

- Ambrose Kingsland (1804–1878), wealthy merchant and mayor of New York City

- Karl Knortz (1841–1918), German-American author and champion of American literature

- Leatherman (c. 1839–c. 1889), distinctive 19th century Northeastern United States vagabond

- Joseph L. Levesque, former President of Niagara University

- Joan Lorring (1926–2014), Academy Award-nominated actress and singer

- Ted Mack (1904–1976), radio and television host best known for The Original Amateur Hour

- Cyrus Margono, professional soccer player

- Ralph G. Martin (1920–2013), author and journalist

- Donald Moffat (1930–2018), British actor

- Frank Murphy (1876-1912), Major League Baseball player

- Eric Paschall, NBA basketball player

- Frederick Philipse (c. 1626–1702), Lord of the Manor of Philipsburg

- Nelson Rockefeller (1908–1979), businessman, politician, the 41st Vice President of the United States

- Adam Savage, co-host of the television show MythBusters

- Gregg L. Semenza, Nobel Prize-awarded physician, researcher, and professor

- Dirck Storm (1630–1716), early colonial American known for the Het Notite Boeck record of Dutch village life in New York

- Tony Taylor, NBA basketball player

- Worcester Reed Warner (1846–1929), mechanical engineer, entrepreneur, manager, astronomer, and philanthropist

- General James Watson Webb (1802–1884), United States diplomat, newspaper publisher, and New York politician

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "QuickFacts Sleepy Hollow village, New York". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ Berger, Joseph (December 11, 1996). "North Tarrytown Votes to Pursue Its Future as Sleepy Hollow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Hoeller, Sophie-Claire (October 28, 2014). "The 6 Most Haunted Towns in the World". Thrillist. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Summers, Ken (October 13, 2014). "Phantom Ships, Headless Skeletons, and Weeping Spirits: Investigating the Real Ghosts of New York's Sleepy Hollow". Week In Weird. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ "The Sleepy Hollow Hauntings". Haunted Places to Go. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow Named Safest Small 'City' in the U.S." July 11, 2021. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Village | Sleepy Hollow, NY". www.sleepyhollowny.gov. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ "About the Area". Sleepy Hollow Tarrytown Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Maika, Dennis J. (2005). "Philipsburg Manor". In Peter Eisenstadt (ed.). Encyclopedia of the State of New York (First ed.). Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. p. 1199. ISBN 081560808X.

- ^ Edited Appletons Encyclopedia, Famous Americans: Biography of Frederick Philipse: "...He worked at the carpenter's trade for several years, aided in building the Old Dutch church, and is said to have made the pulpit with his own hands.

- ^ Egner Gruber, Katherine (October 23, 2024). "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow: Hidden History in an American Ghost Story". American Revolution Museum at Yorktown.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow, NY Population - Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts". CensusViewer. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Police Department". Village of Sleepy Hollow. Archived from the original on August 30, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow Village Court". Law Office of Jared Altman. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "Special Operations Unit". Greenburgh Police Department. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Robert Bonvento (July 28, 2006). "What's Fair and What's Enough..., Negotiating A New Police Contract". River Journal. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Janie Rosman (July 7, 2012). "Sleepy Hollow Firefighters Well Equipped to Protect Village". The Hudson Independent. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "Ambulance Corp". Village of Sleepy Hollow. Archived from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Westchester County, NY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 16, 2024. - Text list

- ^ "Stephen King's 'A Good Marriage' Filming in Sleepy Hollow, NY This Month". OnLocationVacations.com. May 20, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "Hit series 'Man v. Food' takes on Westchester". Lohud.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

External links

edit- Village of Sleepy Hollow official website

- The Hudson Independent (local paper)

- Tarrytown-Sleepy Hollow Patch

- Sleepy Hollow travel guide from Wikivoyage