The Chilean tinamou (Nothoprocta perdicaria) is a type of tinamou commonly found in high elevation shrubland in subtropical regions of central Chile.[3]

| Chilean tinamou | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Order: | Tinamiformes |

| Family: | Tinamidae |

| Genus: | Nothoprocta |

| Species: | N. perdicaria

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nothoprocta perdicaria | |

| Subspecies[2] | |

|

N. p. perdicaria (Kittlitz, 1830) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editAll tinamous are from the family Tinamidae; in the larger scheme, they are also ratites (i.e., birds without a keel on their sternum bone), together with the South American rhea (Rhea), the cassowary (Casuarius), emu (Dromaius), ostrich (Struthio) and the kiwis (order Apterygiformes) as close, if not distant, relatives. However, unlike these terrestrial ratites, tinamou can still fly, albeit not for any sustained period or very effectively. Still, all currently extant ratite species evolved from ancient flying birds, with tinamou representing the closest living connections to these species.[4] Additionally, the tinamou are closely aligned with the extinct giant moa (Dinornis) of New Zealand.

Crypturellus is formed from three Latin or Greek words: kruptos (meaning covered or hidden), oura (meaning tail) and ellus (meaning diminutive). Therefore, Crypturellus translates loosely to "small, hidden tail".[5]

Subspecies

editThe Chilean tinamou has two subspecies, as follows:

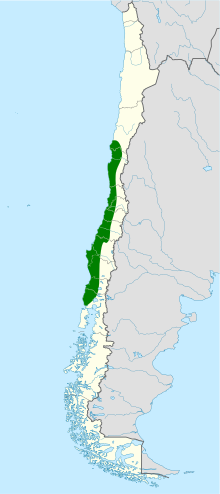

- N. p. perdicaria, the nominate race, occurs in the semi-arid grasslands of north-central Chile; Atacama, Coquimbo, Valparaíso, Santiago, O'Higgins, Maule and Ñuble Regions.[3]

- N. p. sanborni occurs in south-central Chile; Maule, Ñuble, Bio-bio, Araucanía Regions, the northern Los Lagos Region and adjacent Argentina[3]

Distribution and habitat

editThe Chilean tinamou can be found in the high elevation shrubland at 400 to 2,000 m (1,300–6,600 ft) elevation. This species is native to all of Chile except southern Los Lagos, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, Aisén, and Magallanes y Antarctica Chilena.[3][6] This tinamou can also be found in arid mountain forests in association with such trees as Acacia caven, Porlieria chilensis and the endangered Jubaea chilensis.[7] It has been introduced to Easter Island.[8]

Description

editThe Chilean tinamou is approximately 29 cm (11 in) in length. It is almost tail-less and is stocky in shape. It has a bill that is curved and similar to the California quail. It has thick, short, pale, yellowish legs. It generally walks upright and has "short tail and tail coverts drooping behind legs." The pattern on its upper body looks striped, but is more complex in detail. It has a buffy face with a dark eyeline that is drooping and a small strip on its cheek, with a lighter colored crown. Its neck is brown and its lower neck has dark spots. It has a complex patterns that streak on the side of the chest, which is grey. The Chilean tinamou, just south of the Maule Region, has a brownish chest instead of a grey chest and more and reddish brown stripes on its upper body and buttocks. For both regions, it has large wings that cover the body when on ground, and when flying the wings appear large and reddish brown underneath. The wings are also rounded.[9]

It has a loud stride whistle that sounds double-syllabled and sounds like "sweee weee." When under stress, it releases a lowering series of whistles that sounds like "swee wee wee wee" along with fast-paced wing sounds.[9]

Behavior

editThe females lay 10-12 glossy eggs in a scrape. The male incubates the eggs and raises the chicks.[4] The eggs are covered with feathers when left unattended. Incubation is around 21 days. The chicks are buff with dark stripes, and run soon after hatching and fly when half-grown. Later in life blue or gray spots may appear.

Conservation

editThe IUCN classifies the Chilean tinamou as Least Concern,[1] with an occurrence range of 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi).[6]

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2018). "Nothoprocta perdicaria". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22678265A132048936. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22678265A132048936.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Brands, S. (2008)

- ^ a b c d Clements, J (2007)

- ^ a b Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- ^ Gotch, A. F. (1995)

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2008)

- ^ Hogan, Michael C.(2008)

- ^ Jaramillo, A. (2008)

- ^ a b Jaramillo, Alvaro, 28.

References

edit- BirdLife International (2008). "Bartlett's Tinamou - BirdLife Species Factsheet". Data Zone. Retrieved 12 Feb 2009.

- Brands, Sheila (Aug 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Nothoprocta perdicaria". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 12 Feb 2009.[permanent dead link]

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "Tinamous". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Tinamous". Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. p. 183. ISBN 0-8160-3377-3.

- Hogan, Michael C.(2008) Chilean Wine Palm: Jubaea chilensis, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- Jaramillo, A.; Johnson, M. T. J.; Rothfels, C. R.; Johnson, R. A. (2008). "The native and exotic avifauna of Easter Island: then and now" (PDF). Boletin Chileno de Ornitologia. 14: 8–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- Jaramillo, Alvaro. Birds of Chile. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2003). ISBN 0-691-11740-3

External links

edit- Chilean Tinamou videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection