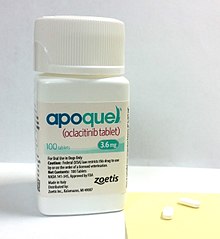

Oclacitinib, sold under the brand name Apoquel among others, is a veterinary medication used in the control of atopic dermatitis and pruritus from allergic dermatitis in dogs at least 12 months of age.[1][4] Chemically, it is a synthetic cyclohexylamino pyrrolopyrimidine janus kinase inhibitor that is relatively selective for JAK1.[5] It inhibits signal transduction when the JAK is activated and thus helps downregulate expression of inflammatory cytokines.[medical citation needed]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Apoquel |

| Other names | PF-03394197 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Veterinary Use |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | JAK inhibitor |

| ATCvet code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 89%[1] |

| Protein binding | 66.3–69.7%[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 3.1–5.2 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Mostly liver[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H23N5O2S |

| Molar mass | 337.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Oclacitinib was approved for use in the United States in 2013,[4] and in the European Union in 2023.[2][6]

Uses

editOclacitinib is labeled to treat atopic dermatitis and itchiness (pruritus) caused by allergies in dogs, though it has also been used to reduce the itchiness and dermatitis caused by flea infestations.[7][8] It is considered to be highly effective in dogs, and has been established as safe for at least short-term use.[9][10][11] Its efficacy equals that of prednisolone at first, though oclacitinib has been found to be more effective in the short term in terms of itchiness and dermatitis, long term safety is unknown.[12] It has been found to have a faster onset and cause less gastrointestinal issues than cyclosporine.[10][13]

While safe in the short term, oclacitinib's long-term safety is unknown.[10][14] While some say it is best only for acute flares of itchiness, others claim that it is also useful in chronic atopic dermatitis.[8][14]

There is some off-label use of oclacitinib in treating asthma and allergic dermatitis in cats, but the exact efficacy has not been established.[12][8]

Contraindications

editOclacitinib is not labeled for use in dogs younger than one due to reports of it causing demodicosis.[13] It should also be avoided in dogs less than 3 kg (6.6 lb). Most of the other contraindications are avoiding cases where a potential side effect exacerbates a pre-existing condition: for example, because oclacitinib can cause lumps or tumors, it should not be used in dogs with cancer or a history of it;[15] because it is an immune system suppressant, it should not be used in dogs with serious infections.[10]

Oclacitinib, by virtue of its low plasma protein binding, has little chance of reacting with other drugs. Nonetheless, concurrent use of steroids and oclacitinib has not been tested and is thus not recommended.[10]

Side Effects

editOclacitinib lacks the side effects that most JAK inhibitors have in humans; instead, side effects are infrequent, mild, and mostly self-limiting.[13][14][16] The most common side effects are gastrointestinal problems (vomiting, diarrhea, and appetite loss) and lethargy. The GI problems can sometimes be alleviated by giving oclacitinib with food.[10][15] New cutaneous or subcutaneous lumps, such as papillomas, can appear,[10][17] and dogs face an increased susceptibility to infections such as demodicosis.[1][15] There is a transient decrease in neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes, as well as in serum globulin, while cholesterol and lipase levels increase. The decrease in white blood cells lasts only around 14 days. None of the increases or decreases are clinically significant (i.e. none push their corresponding values out of normal ranges).[1][17][18]

Less common side effects of oclacitinib include bloody diarrhea; pneumonia; infections of the skin, ear, and/or urinary tract; and histiocytomas (benign tumors). Increases in appetite, aggression, and thirst have also been reported.[10][15]

Pharmacodynamics

editMechanism of Action

editOclacitinib is not a corticosteroid or antihistamine, but rather modulates the production of signal molecules called cytokines in some cells.[13] Normally, a cytokine binds to a JAK (Janus kinase) receptor, driving the two individual chains to come together and self-phosphorylate. This brings in STAT proteins, which are activated and then go to the nucleus to increase transcription of genes coding for cytokines, thus increasing cytokine production.[19]

Oclacitinib inhibits signal JAK family members (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2), most effectively JAK1, while not significantly inhibiting non-JAK kinases.[5][19]

| Receptor | Mean IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|

| JAK1 | 10 |

| JAK2 | 18 |

| JAK3 | 99 |

| TYK2 | 84 |

This causes the inhibition of pro-inflammatory and pruritogenic (itch-causing) cytokines that depend on JAK1 and JAK3, which include IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, and IL-31[1][12][13] (TSLP, another pruritogenic cytokine that uses JAKs, has also been found to be inhibited).[20][21] IL-31 is a key cytokine at the pruritogenic receptors at neurons near the skin, and also induces peripheral blood mononuclear cells and keratinocytes to release pro-inflammatory cytokines.[16] Suppression of IL-4 and IL-13 causes a decrease of Th2-cell differentiation, which plays a role in atopic dermatitis.[19] Oclacitinib's relatively little effect on JAK2 prevent it from suppressing hematopoiesis or the innate immune response.[7][13]

Oclacitinib inhibits JAK, not the pruritogenic cytokines themselves; studies in mice showed that suddenly stopping the medication caused an increase in itchiness caused by a rebound effect, where more cytokines were produced to overcome lack of response by JAK.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

editOclacitinib is absorbed well when taken orally; it takes less than an hour to reach peak plasma concentration and has a bioavailability of 89%.[1] In most dogs, pruritus begins to subside within four hours and is completely gone within 24. Oclacitinib is cleared mostly by being metabolized in the liver, though there is some kidney and bile duct clearance as well.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Apoquel- oclacitinib maleate tablet, coated". DailyMed. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Prolevare EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 February 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ "Apoquel EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ a b "FDA Approves Apoquel (oclacitinib tablet) to Control Itch and Inflammation in Allergic Dogs" (Press release). Zoetis. 16 May 2013. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ a b Gonzales AJ, Bowman JW, Fici GJ, Zhang M, Mann DW, Mitton-Fry M (August 2014). "Oclacitinib (Apoquel) is a novel Janus kinase inhibitor with activity against cytokines involved in allergy". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 37 (4): 317–324. doi:10.1111/jvp.12101. PMC 4265276. PMID 24495176.

- ^ "Prolevare Film-coated tablet". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 23 April 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ a b Cowan A, Yosipovitch G (2015). Pharmacology of Itch. Springer. pp. 363–364. ISBN 978-3-662-44605-8.

- ^ a b c Hnilica KA, Patterson AP (2016). Small Animal Dermatology - E-Book: A Color Atlas and Therapeutic Guide. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-323-39067-5.

- ^ Cote E (2014). Clinical Veterinary Advisor - E-Book: Dogs and Cats. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1765. ISBN 978-0-323-24074-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Falk E, Ferrer L (December 2015). "Oclacitinib" (PDF). Clinician's Brief. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Moriello K. "Canine Atopic Dermatitis". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Papich MG (2015). Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs: Small and Large Animal. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-323-24485-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Riviere JE, Papich MG (2017). Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2955–2966. ISBN 978-1-118-85588-1.

- ^ a b c Saridomichelakis MN, Olivry T (January 2016). "An update on the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis". Veterinary Journal. 207: 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.09.016. PMID 26586215. S2CID 9511235.

- ^ a b c d Barnette C (2017). "Oclacitinib". VCA. LifeLearn. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ a b Layne EA, Moriello KA (1 April 2015). "What's new with an old problem: Drug options for treating the itch of canine allergy". dvm360. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Apoquel, INN-oclacitinib maleate" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, Walsh KF, Follis SI, King VI, et al. (December 2013). "A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of the Janus kinase inhibitor oclacitinib (Apoquel) in client-owned dogs with atopic dermatitis". Veterinary Dermatology. 24 (6): 587–97, e141-2. doi:10.1111/vde.12088. PMC 4286885. PMID 24581322.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ a b c Damsky W, King BA (April 2017). "JAK inhibitors in dermatology: The promise of a new drug class" (PDF). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 76 (4): 736–744. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.005. PMC 6035868. PMID 28139263. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Olivry T, Mayhew D, Paps JS, Linder KE, Peredo C, Rajpal D, et al. (October 2016). "Early Activation of Th2/Th22 Inflammatory and Pruritogenic Pathways in Acute Canine Atopic Dermatitis Skin Lesions". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 136 (10): 1961–1969. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.117. PMID 27342734.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ a b Fukuyama T, Ganchingco JR, Bäumer W (January 2017). "Demonstration of rebound phenomenon following abrupt withdrawal of the JAK1 inhibitor oclacitinib". European Journal of Pharmacology. 794: 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.11.020. PMID 27847179. S2CID 41919568.