The Ocmulgee River (/ɒkˈmʌlɡiː/) is a western tributary of the Altamaha River, approximately 255 mi (410 km) long, in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the westernmost major tributary of the Altamaha.[1] It was formerly known by its Hitchiti name of Ocheese Creek, from which the Creek (Muscogee) people derived their name.

| Ocmulgee River | |

|---|---|

Ocmulgee River in Monroe County Recreational Park | |

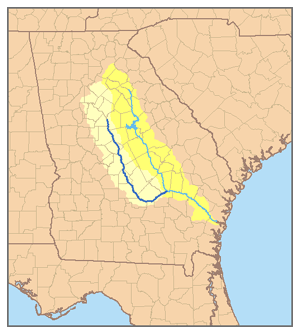

Map of the Ocmulgee River watershed highlighted; river is dark blue | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Confluence of South, Yellow, and Alcovy rivers |

| • location | Lloyd Shoals Dam |

| • coordinates | 33°19′15″N 83°50′39″W / 33.32083°N 83.84417°W |

| Mouth | Altamaha River |

• location | Hazlehurst |

| Length | 255 mi (410 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | South River |

| • right | Yellow River, Alcovy River |

The Ocmulgee River and its tributaries provide drainage for some 6,180 square miles in parts of 33 Georgia counties, a large section of the Piedmont and coastal plain of central Georgia.[1]

The Ocmulgee River basin has three river subbasins designated by the U.S. Geological Survey: the Upper Ocmulgee River subbasin (hydrologic unit code 03070103); the Lower Ocmulgee River Subbasin (03070104); and the Little Ocmulgee River Subbasin (03070105).[2]

The name of the river may have come from a Hitchiti words oki ("water") plus molki ("bubbling" or "boiling"),[3] possibly meaning "where the water boils up."[1]

Description

editThe river rises at a point in north central Georgia southeast of Atlanta, at the confluence of the Yellow, South, and Alcovy rivers.[1] Since the construction of the Lloyd Shoals Dam in the early 20th century, these rivers join as arms of the Jackson Lake reservoir.[1] The river's source is formed at an elevation of around 530 feet above sea level.[1]

The Ocmulgee River flows from the dam southeast past Macon, which was founded on the Fall Line. It joins the Oconee from the northwest (241 miles downstream from Jackson Lake) to form the Altamaha near Lumber City.[1] The Ocmulgee River Water Trail begins from Macon's Amerson River Park to the confluence near Lumber city and Hazelhurst, encompassing approximately 200 miles.[4]

Human use

editFour power plants in the Ocmulgee basin that use the river's water, including the coal-fired Plant Scherer in Juliette, operated by the Georgia Power Company.[5] Plant Scherer is the seventh-largest power plant in the United States by capacity (based on 2016 data)[update], and the largest to be fueled exclusively by coal.[6]

Fish fauna

editA diverse array of fish—105 species in twenty-one families—inhabit the Ocmulgee River basin.[2] The family with the largest representation in the river basin is Cyprinidae (carp and true minnows), with 27 species.[2] It is followed by Centrarchidae (sunfish), which has 22 species.[2] The Ocmulgee basin contains ten species in the family Ictaluridae (catfish) and eight species of in the family Catostomidae (suckers).[2] The river basin is also inhabited by one State of Georgia-designated endangered fish species, the Altamaha shiner (Cyprinella xaenura) and two designated rare species, the goldstripe darter (Etheostoma parvipinne) and redeye chub (Notropis harperi).[2]

The Ocmulgee River is popular with anglers for its excellent fishing, particularly for redbreast sunfish, bluegill, redear sunfish, largemouth bass, black crappie, channel catfish, and flathead catfish.[2] The world record for largest recorded catch of a largemouth bass was achieved in 1932 in Montgomery Lake, an oxbow lake off the Ocmulgee River in Telfair County.[2][7] The record-setting fish, caught by farmer George Washington Perry, weighed 22 pounds, 4 ounces.[7][8] The International Game Fish Association officially declared the world record for largemouth bass tied in 2010, following Manabu Kurita's catch (in July 2009) of a 22 pound, 4 ounce largemouth taken from Lake Biwa in Japan.[9]

There are some fifteen invasive species of fish which inhabit the river basin.[2] According to a Georgia Department of Natural Resources report, "many of these species are well-established and are detrimental to native fish populations.[2] The fifteen invasives are threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense), goldfish (Carassius auratus), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), blacktail shiner (Cyprinella venusta); common carp (Cyprinus carpio); flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris); white bass (Morone chrysops); morone hybrids (Morone sp.); green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus); longear sunfish (Lepomis megalotis); Lepomis hybrids (Lepomis sp.); shoal bass (Micropterus cataractae); spotted bass (Micropterus punctulatus); white crappie (Pomoxis annularis); and yellow perch (Perca flavescens).[2]

History

editArcheological evidence shows that Native Americans first inhabited the Ocmulgee basin about 10,000 to 15,000 years ago (see settlement of the Americas).[1] Scraping tools and flint spearpoints from nomadic Paleoindians hunters have been discovered in the Ocmulgee floodplain.[1]

In the Archaic period (c. 8000-1000 BCE) which followed, hunter-gatherers in Ocmulgee basin used fiber-tempered pottery and stone tools.[1] During the Woodland period (c. 1000 BCE-900 CE), there were various villages in the area, evidenced by earthen mounds and pottery sherds.[1]

There is evidence that the Mississippian culture reached the Ocmulgee basin by 900 CE; according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, "on the Macon plateau and in the nearby Ocmulgee bottomlands, stretches of farmsteads and gardens constructed around elaborate ceremonial mounds are the most prominent evidence of this early Mississippian influence."[1] These areas are now part of the Ocmulgee National Monument, a National Park Service-administered protected area established in 1936.[1]

Europeans first explored the Ocmulgee basin in 1540, during the expedition of the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his party, who visited the late Mississippian chiefdom of Ichisi, now identified by archeologists as the floodplain south of Macon.[1] The Ichisi served corncakes, wild onion, and roasted venison to De Soto and his party.[1] Over the next hundred years, however, the Native Americans in the area were devastated from disease and chaos following European contact.[1]

Between 1689 and 1692, a number of towns of the Apalachicola Province located on the Chattahoochee River moved to central Georgia, settling in the area of the Ocmulgee River, which the English at the time called Ochese Creek. In 1715, the English recorded ten towns among the "Ochese Creek Indians" (which the Spanish called "Uchese"), with a population of 2,406. Early 18th century maps show a total of twelve towns in the vicinity of Ochese Creek, many with names corresponding to towns that had been on the Chattahoochee River. The Muscogee-speaking towns of Coweta, Kasihta, Tuskegee, and Koloni were located on the north side of the cluster. Several of the Hitchiti-speaking towns were located to the southern part of the Ochese Creek cluster, including Ocmulgee, Hitchiti, and Osuchi. Two Muskogee-speaking towns from the Tallapoosa River in Alabama, Atasi and Kealedji, joined the cluster of towns around Ochese Creek, as did the Hitchiti-speaking town of Chiaha from western North Carolina. The Ochese Creek cluster also included Westo and Yuchi towns. Following the outbreak of the Yamassee War in 1715, the Ochese Creek towns moved west, mostly returning to the Chattahoochee River, where they evolved into the Lower Towns of the Muscogee Confederacy (referred to by the English as the "Lower Creeks").[10]

Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin stimulated development of short-staple cotton plantations in the uplands, where it grew well. The gin mechanized processing of the cotton and made it profitable. Demand for land in the Southeast increased, as well as demand for slave labor in the Deep South. In 1806, the U.S. acquired the area between the Oconee and Ocmulgee rivers from the Creek Indians by the First Treaty of Washington. That same year United States Army established Fort Benjamin Hawkins overlooking the Ocmulgee Fields. In 1819 the Creek held their last meeting at Ocmulgee Fields. they ceded this territory in 1821.

In the same year, the McCall brother established a barge-building operation at Macon. The first steamboat arrived on the river in 1829. During the 19th century, the river provided the principal water navigation route for Macon, allowing the development of the cotton industry in the surrounding region. In 1842 the river was connected by railroad to Savannah. The river froze from bank to bank in 1886. In 1994 devastating floods on the river after heavy rains caused widespread damage around Macon.[11]

Ocmulgee creeks

editMajor creeks that flow into the Ocmulgee River include:

- Tucsawhatchee Creek

- This tributary is largely known as "Big Creek" on most maps. While USGS does recognize Tucsawhatchee Creek, even their maps name it as "Big Creek."[12]

- Echeconnee Creek

- This tributary's name means "deer trap" in the Muscogee language, the language of the Creek. It refers to the steep incline of the creek where Creeks would trap deer, luring them into steep areas and then charging them.

- Alligator Creek

- Big Indian Creek

- Coley Creek

- Big Horse Creek

- Flat Creek

- Folsom Creek

- Horse Creek

- Jordan Creek

- Limestone Creek

- Little Ocmulgee River (Gum Swamp Creek)

- Little Shellstone Creek

- Little Sturgeon Creek

- Mossy Creek

- Otter Creek

- Richland Creek

- Sandy Run Creek

- Savage Creek

- Shellstone Creek

- South Shellstone Creek

- Sturgeon Creek

- Sugar Creek

- Ten Mile Creek

- Tobesofkee Creek

- Walnut Creek

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ocmulgee River, New Georgia Encyclopedia (August 9, 2004).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ocmulgee River Basin Plan, Section 2: River Basin Characteristics, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Environmental Protection Division.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Ocmulgee River Water Trail | Georgia River Network". Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Ocmulgee River: Quick Facts about the River, Georgia River Network (accessed June 6, 2015).

- ^ "Electricity in the United States - Energy Explained, Your Guide To Understanding Energy - Energy Information Administration". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- ^ a b Richard J. Lenz, Highroad Guide to the Georgia Coast and Okefenokee (Longstreet Press: 1999), p. 199.

- ^ Monte Burke, Sowbelly: The Obsessive Quest for the World-Record Largemouth Bass (Penguin Group USA, 2006), p. xiii.

- ^ Dale Bowman, World-record largemouth bass tie: Formal word, Sun-Times (January 8, 2010).

- ^ Worth, John E. (2000). "The Lower Creeks: Origin and History" (PDF). In McEwan (ed.). Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory (Bonnie G. ed.). University of Florida Press. pp. 278–286. ISBN 9-780-8130-2086-0.

- ^ "1994 flood", Centers for Disease Control

- ^ "Tucsawhatchee Creek Near Hawkinsville, GA".

- Snow, Dean (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-0-13-615686-4.

Relevant readings

edit- Watson, Chris. 2022. The Wild and the Sacred: Evaluating and Protecting the Ocmulgee River Corridor, Vol. 1. Series edited by S. Heather Duncan. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Day, Dominic. 2022. A River of Time: Archaeological Treasures of the Ocmulgee Corridor, vol. 2. Series edited by S. Heather Duncan. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Bigman, Daniel Philip. From Settlement to Society: A History of the Early Mississippian Settlement at Ocmulgee, Volume 3. Series edited by S. Heather Duncan. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.