The Perth Observatory is the name of two astronomical observatories located in Western Australia (WA). In 1896, the original observatory was founded in West Perth on Mount Eliza overlooking the city of Perth (obs. code 319). Due to the city's expansion, the observatory moved to Bickley in 1965. The new Perth Observatory is sometimes referred to as Bickley Observatory (obs. code 322, 323).[1]

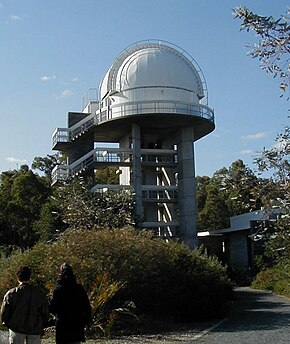

Perth Observatory's 61-centimetre telescope dome at Bickley | |

| Observatory code | 319 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bickley, City of Kalamunda, City of Kalamunda, Australia |

| Coordinates | 32°00′28″S 116°08′09″E / 32.00781°S 116.13579°E |

| Altitude | 428 m (1,404 ft) |

| Established | 1900 |

| Website | www |

| | |

| Type | State Registered Place |

| Designated | 19 July 2005 |

| Reference no. | 10551 |

History

editFirst Perth Observatory

editThe original Perth Observatory was constructed in 1896 and was officially opened in 1900 by John Forrest, the first premier of Western Australia. The observatory was located at Mount Eliza overlooking the city of Perth. Its chief roles were keeping Standard Time for Western Australia and meteorological data collection. The observatory dome was demolished in the 1960s to make way for Dumas House, after the Observatory of the city was relocated elsewhere. The house of the chief astronomer of the old observatory remains today, the current tenant is the National Trust.[2]

WA Government Astronomers

editWilliam Ernest Cooke

editWilliam Ernest Cooke was appointed the first Western Australian Government Astronomer in 1896 after a similar posting at the Adelaide Observatory. On arrival in Perth, his first task was to determine the exact latitude and longitude of the colony. He was also able to determine the time of day with greater accuracy. Before his arrival clocks could vary by up to half an hour. The time was announced each day by a cannon still present on the grounds. The design was by the government architect, George Temple-Poole, and features a bold combination of styles.[citation needed]

Harold Burnham Curlewis

editCooke's successor as Government Astronomer was Harold Curlewis who wrote in 1929:

Since the prevailing winds blow over the huge extent of King's Park, its excellence for astronomical work is not impaired by its proximity to the city, as is so often the case with other observatories. ...A glance from the tower, from which a wonderful panorama of Perth may be obtained, shows that no growth of the city can ever adversely affect observing conditions[3]

Curlewis and the WA border

editIn 1920 and 1921 Curlewis was involved with the Government Astronomer of South Australia, Dodwell, in determinations to fix positions for marking of the West Australian border on the ground with the South Australian border at Deakin, Western Australia. In 1921 the same group from the Deakin determinations travelled by the State Ship, MV Bambra to Wyndham, where they were guided by M.P. Durack to a point on Rosewood station near Argyle Downs close to the 129th meridian east longitude (129° east). They used the relatively new technology of the day, wireless radio time signals, and other methods to fix a position for the Northern Territory border with Western Australia.[4]

These early determinations led to the 1968 agreement for the formation of Surveyor Generals Corner.

The WA border is not straight (see Western Australia border); at the 26th parallel south (26° south) there is an approximately 127-metre (417 ft) "sideways" section of the WA/NT border, which runs east–west.[4]

Hyman Solomon Spigl

editCurlewis's successor as Government Astronomer was Hyman Solomon Spigl between 1940 and 1962. Spigl, who was from a surveying background, progressed rebuilding a post war ravaged Observatory by rejuvenating the time service, seismology services, completing the Astrographic Catalogues, became involved in the International Geophysical Year by installing a Markowitz Moon camera and restarted the publications for the Royal Astronomical Society. Additionally, through a National Science Foundation of America grant, he was in the process of refurbishing the Observatory's 150-millimetre (6 in) meridian transit circle to recommence meridian observations. While he never achieved this before his death, and it was never used again, the instrument sits in the foyer of the Perth Observatory now fully refurbished.

In 1958 Spigl was awarded a Gledden Travelling Fellowship by the University of Western Australia; Spigl spent 12 months travelling in the US, UK and Europe. Spigl was actively searching for a new site for the Perth Observatory as a result of the decision for it to be relocated as an outcome of the implementation of the 1955 Stephenson-Hepburn Report. Spigl spent many years lecturing in surveying at the University of Western Australia and was involved in the Astronomical Society of Western Australia.

John Bertrand Harris

editUpon the death of Spigl on 20 August 1962, John Bertrand Harris, who had been Spigl's assistant since 1957, became the fourth Government Astronomer of the Perth Observatory between 1962 until the end of 1974.[5] Harris had to step in to the position of Government Astronomer at a time when the Perth Observatory was on the move to its new site in the Darling Range, Bickley, some 24 kilometres (15 mi) east of its original position in the City of Perth. Clearing of the land in the State Forrest in Bickely commenced in February 1964, with excavations commencing in May 1964 and construction works on buildings continuing through 1965; staff moved in on 19 December 1965.

With the new Bickely site complete, in 1967, Harris oversaw the installation of a meridian circle telescope at the Observatory as part of an expedition by astronomers from the Hamburg Observatory in Germany. The expedition worked on the international Southern Reference Stars program that resulted in a revised, larger and more accurate meridian catalogue of the Southern Hemisphere: the Perth 70 meridian catalogue. In 1970 Harris was successful in forming a dedicated Perth Observatory Meridian section to assist the German expedition in their work. After the German expedition left over the 1971/72 Christmas/New Year period, Harris successfully negotiated the loan of the Hamburg telescope indefinitely and obtained funding from the Government of Western Australia to increase the Meridian staff numbers. This Perth Observatory Meridian team continued and expanded on the German expedition work, resulting in the Perth 75 meridian catalogue.

In 1967, Harris worked with the University of Western Australia to install a 410-millimetre (16 in) telescope at the Observatory that was built and used by the University of Western Australia staff and students, as well as Perth Observatory astronomers.

Harris then moved the astrographic telescope, which had been in storage since August 1963, to the new site after arranging its refurbishment; the telescope recommenced observations on 29 March 1968, taking second epoch photographic plates for proper motion studies.

In 1968, the Lowell Observatory of Flagstaff Arizona USA, located a 610-millimetre (24 in) Boller and Chivens telescope at the Perth Observatory as part of the International Planetary Patrol Program. The program was designed to collect 35-mm format photographic data on the atmospheric and surface features of Solar System planets, mostly Mars, Jupiter and Venus; Harris was to be a regular observer outside his normal daytime Government Astronomer role.

Harris was successful in increasing the technical and astronomical staff numbers at the new Bickley Perth Observatory as its role moved to that of more of a scientific function, however Harris also restarted the public tours on 23 October 1966 and maintained the provision of information services to Western Australia. Harris also continued time and tide services for Western Australia, however as had been the case in 1908 for Meteorology, the move saw seismic monitoring activities being relocated to Mundaring under the Commonwealth Government control.

Harris was responsible for the August 1973 IAU Symposium No. 61 in Perth on "New Problems of Astrometry". Like his predecessor, he died at an early age, 49, but had raised the standing of the Perth Observatory to a well respected scientific institution within Australia and internationally.[citation needed]

Dr Iwan (Ivan) Nikoloff

editWith the death of Harris on 23 December 1974, Nikoloff was to act in the role of Government Astronomer of the Perth Observatory until 30 May 1979 when he officially became the fifth Government Astronomer of the Perth Observatory.

After arriving in Australia in 1964, he commenced at the Perth Observatory as an Astronomer Grade II on 1 May 1964 and worked on the Observatory's astrograph; his previous experience also saw him set up and calibrate the recently acquired Zeiss plate measuring machine. With the relocation of the Perth Observatory from Perth to Bickley, Nikoloff's surveying skills were extensively used in setting up the new Observatory during 1965.

Nikoloff worked with the German Hamburg Observatory meridian circle telescope expedition on the Perth 70 catalogue, from 1969 until 1971, before the expedition astronomers returned to Germany that Christmas.

In 1971, with funding by the Government of Western Australia and negotiations for the loan of the Hamburg telescope, Nikoloff was placed in charge of the newly formed Perth Observatory Meridian Section. Dr Nikoloff commenced a new observing program of FK4 and FK4 Supplementary stars that would result in the Perth 75 catalogue of 2549 stars. The catalogue not only extended the well revered Perth 70 catalogue, but provided valuable Southern Hemisphere information for the construction of the new FK5 reference frame sought by the international astronomical community.

As Government Astronomer, Nikoloff passed on the Meridian Section to D. Harwood, but kept a keen involvement in the construction of the subsequent Perth 83 meridian catalogue. While daily administrative duties kept him busy, Nikoloff continued observing on all the Observatory's telescopes at night and on weekends.

Nikoloff maintained a good relationship with the University of Western Australia, was a Foundation member and Fellow of the Astronomical Society of Australia, a life member of the Astronomical Association of Western Australia and a member of the IAU's original Commission 8 (Astrometry) and I (Fundamental Astronomy); he also continued the Observatory's public information services and tours. He retired on 4 January 1985 and died on 8 April 2015.

Perth Observatory Directors

editUpon the retirement of Dr I Nikoloff, the governing body of the Perth Observatory at that time, the Department of Science and Technology (Australia), replaced the primary title of what was previously called the Government Astronomer, with the title of Director Perth Observatory. The reason given was that the title of Government Astronomer "...seemed antiquated to them",[6] it also reflected similar changes throughout the world with astronomical institutions merging with Universities.

Michael Philip Candy

editWith the compulsory retirement age still in place, after Dr I Nikoloff retired, Mr Michael Philip Candy became the first Director of the Perth Observatory.

In 1969 Candy was offered the position of Director of the British Astronomical Association, however declined due to his plans to emigrate to Australia that year.

After arriving in Australia 12 May 1969, he commenced at the Perth Observatory as an Astronomer Grade II and in November 1969 took over the running of the Perth Observatory Astrographic telescope from Dr I Nikoloff.

His numerical prowess, gained during his time at HM Nautical Almanac Office, was to be a great asset in the astrometric programs of the Perth Observatory, as was his interest in comets.

It took little time for Candy to position the Perth Observatory at the forefront of southern cometary astrometry. By 1972, the Perth Observatory was 9th in the world in producing cometary positions. Not content with this, Candy introduced new photographic glass plate processing practices to increase the limiting magnitude of objects achievable at that time from 14th to 19th. The new processes were to see the recovery of five comets and the positioning of the Observatory to 2nd place between 1973 and 1977 and 4th between 1978 and 1984, resulting in him being awarded the prestigious Merlin Medal of the British Astronomical Association in 1975. Under his direction the Perth Observatory discovered over 100 new asteroids as well as contributing a significant number of observations to the Minor Planet Center.

He continued the first publication of the Perth Observatory on comet and minor positions, commenced by Mr B Harris, with Communication No. 2, 3, 4 and the last, that of Communication No. 5 in 1986.

By 1979 his astrometric abilities and contributions were widely acknowledged and he became Vice President of International Astronomical Union, Commission 6, a position he held until 1982 when he was elected president for a 3-year term. At the same time became a working member of International Astronomical Union Commission 20 until 1988 – Positions and Motions of Minor Planets, Satellites and Comets.

The Perth Observatory was positioned well for Halley's Comet in 1986/1987 and under Candy the Perth Observatory produced 10% of all Earth based astrometric positions for the comet, the largest contribution in the World.

Candy was a councillor of the Astronomical Society of Australia from 1988 to 1990, councillor of the Royal Society of Western Australia between 1988 and 1990, and president of the Royal Society of Western Australia in 1989 .

He saw the most drastic staff cuts to the Observatory by the Government in 1987 with 50% of the staff redeployed and one whole section closed down.[6]

With the compulsory retirement age no longer in place, unlike his predecessor, Candy was able to continue working at the Perth Observatory on projects including the eclipsing binary FO Hydra, a comet hunter telescope, a new theory on comet origins and evolution, the analysis of the lost comet Gale, as well as comparison of a South Australian comet discovered in 1979 with that of a comet from 1770.

In 1960 he discovered Comet Candy 1960n and was the first Astronomer to discover, as well as compute, a comets orbit from two more observations within 60 hours of its discovery.

Mr M P Candy officially retired on 24 December 1993 and died 2 November 1994.[7]

His work was honored by the naming of Minor Planet 3015 Candy in 1980.

James D Biggs

editDr James D Biggs commenced at the Perth Observatory in May 1994 and resigned in 2010.[6]

Ralph Martin (Acting)

editAfter Dr J D Biggs resigned, Ralph Martin acted in the Directors position until on 22 January 2013 the WA Government announced that all research programs would be cut and the Observatory would only be open for tours.[8]

Martin and the remaining staff of the Perth Observatory took voluntary redundancy.[6]

Earthquake records

editAs an earthquake observatory in Perth a Milne-Shaw seismograph was utilised between 1923 and 1959 for the recording of earthquakes in Western Australia. After 1959 the earthquake monitoring was taken up by the Mundaring Geophysical Observatory.[9]

New observatory at Bickley

editIn the 1960s, light pollution from the city of Perth and a small part of the implementation of the 1955 plan by Stephenson-Hepburn Report saw the land where the Perth Observatory resided make way for what was to initially be five government office blocks, however there was only one ever built, Dumas House. After nearly being closed by the State Government, the Observatory was moved to its current site at Bickley near Mount Gungin in the Darling Range. Construction of the new observatory cost $600,000, and it was opened by the Premier Sir David Brand on 30 September 1966.

Recent history

editThe Observatory has fought off several attempts to close the facility by the State Government, the most serious being in 1987 when it was part of the Department of State Services. An outcry from the public, scientific and amateur communities was helpful in retaining the observatory.

As of July 2015, The Perth Observatory Volunteer Group runs the Observatory under a community partnership agreement between the Department of Parks and Wildlife and the Perth Observatory Volunteer Group which was signed in June 2015.

Centenary 1996

editIn January 1996, the centenary of its foundation, the observatory was transferred to the Department of Conservation and Land Management, now part of the Department of Parks and Wildlife (Western Australia).[10]

Bickley Observatory heritage listed

editIn 2005 the Bickley site was heritage listed, being Australia's oldest continuing operating observatory and Australia's only remaining State Government operated astronomical observatory.[11]

Publication

editThe Western Australian astronomy almanac was published in the 2000s by the DEC as part of the Observatory expertise, utilising staff of the Observatory to edit and contribute. The 2002 publication for the 2003 almanac had an extra subtitle which was not utilised in later editions: the really useful guide to the wonders of the night sky.[12][13]

It had been preceded by Astronomical Data (1965–1990)[14] and the Astronomical Handbook (1989–1992 ?).[15]

Perth Observatory today

editThe Minor Planet Center credits 29 minor planet discoveries to Perth Observatory for the period between 1970 and 1999.[16]

On 22 January 2013 the Western Australian Government announced that all research programs would be cut and the Observatory would only be open for tours.[8]

As of 1 July 2015, the Perth Observatory Volunteer Group has been running the Observatory for the Western Australian Government, the Perth Observatory continues to operate today under the management of only 3 part-time staff and almost 120 volunteers.

In 2022-23, 14,992 people were reached by Perth Observatory programs, and 771 school students experienced a lesson at the observatory. 179 night sky tours were held, with 5810 people experiencing a night sky tour. There were 1516 daytime walk-in visitors to the observatory. 26 off-site events were conducted throughout the state.

There were 162 registered volunteers who contributed 20,560 hours of volunteer time.[17]

Honors

editThe Florian asteroid 3953 Perth was named in honour of the observatory.[1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(3953) Perth". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (3953) Perth. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 337. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_3941. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ^ "Old Observatory - Heritage Perth".

- ^ H B Curlewis (20 July 1929). "The Perth Observatory". Civil Service Journal: 73–74.

- ^ a b Porter J, Surveyor-General of South Australia (April 1990). AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE - Longitude 129 degrees east, and why it is not the longest, straight line in the world. National Perspectives – 32nd Australian Surveyors Congress Technical Papers 31 March – 6 April 1990. Eyepiece – Official Organ of The Institution of Surveyors, Australia, W.A. Division. Canberra: The Institution: The Institution of Surveyors, Australia, W.A. Division (published June 1990). pp. 18–24.

- ^ "Harris, Bertrand John (1925–1974)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ a b c d Bowers, Craig (2016). The Scientific History of the Perth Observatory from 1960 to 1993. Murdoch University. p. 276. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Obituary – Candy, Michael-Philip – 1928–1994". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 105: 56. 1995. Bibcode:1995JBAA..105...56.

- ^ a b "Research programs to be cut at Perth Observatory". ABC News. 22 January 2013.

- ^ Gordon, F.R and J.D. Lewis (1980) The Meckering and Calingiri earthquakes October 1968 and March 1970 Geological Survey of Western Australia Bulletin 126 ISBN 0-7244-8082-X – Appendix 1 – page 213 Catalogue of Larger Earthquakes recorded in Southwestern Australia and in National archives ref CA 3539 Mundaring Geophysical Observatory, WA http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/scripts/AgencyDetail.asp?M=0&B=CA_3539[permanent dead link]

- ^ Spreading the Word – Western Style: Education and Public Awareness Programmes at Perth Observatory James Biggs, Astronomical Society of Australia 1997. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ^ "Perth Observatory". Heritage Council, State Heritage Office. 8 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Perth Observatory (2002), Western Australian astronomy almanac 2003 : the really useful guide to the wonders of the night sky, Perth Observatory, ISBN 978-0-9581963-0-7

- ^ Western Australia. Dept. of Conservation and Land Management; Perth Observatory (2000), Western Australian astronomy almanac, Perth Observatory, retrieved 17 March 2013 (2003 – 2012, not published in 2011 )

- ^ Perth Observatory (1965), Astronomical data, The Observatory, retrieved 17 March 2013

- ^ Perth Observatory (1989), Astronomical handbook, The Observatory, retrieved 17 March 2013

- ^ "Minor Planet Discoverers (by number)". Minor Planet Center. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ https://www.perthobservatory.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022-23-POVG-Annual-Report.pdf [bare URL PDF]

Publication

edit- Western Australian astronomy almanac. Bickley, W.A. Perth Observatory. ISBN 0-9581963-6-2 (2007 edition)