Olympia is a 1938 German documentary film written, directed and produced by Leni Riefenstahl, which documented the 1936 Summer Olympics, held in the Olympic Stadium in Berlin during the Nazi period. The film was released in two parts: Olympia 1. Teil — Fest der Völker (Festival of Nations) (126 minutes) and Olympia 2. Teil — Fest der Schönheit (Festival of Beauty) (100 minutes). The 1936 Summer Olympics torch relay, as devised for the Games by the secretary general of the Organizing Committee, Dr. Carl Diem, is shown in the film.

| Olympia | |

|---|---|

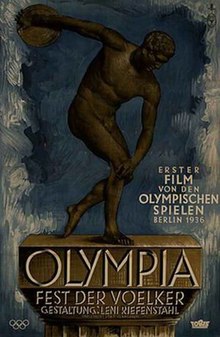

Part 1 poster | |

| Directed by | Leni Riefenstahl |

| Written by | Leni Riefenstahl |

| Produced by | Leni Riefenstahl |

| Cinematography | Paul Holzki |

| Edited by | Leni Riefenstahl |

| Music by | |

Production company | Olympia-Film |

| Distributed by | Tobis |

Release date |

|

Running time | 226 minutes |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Budget | 2.35 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ |

Olympia is controversial due to its political context and propaganda value. However, the techniques Riefenstahl employed are almost universally admired and had a lasting influence on film and television coverage of sport events. Olympia appears on many lists of the greatest films of all time, including Time magazine's "All-Time 100 Movies".[1]

Production

editThe Nazis planned on using the 1936 Summer Olympics as a piece of propaganda. Riefenstahl claimed that the film was commissioned by the International Olympic Committee, but it was financed entirely by the government using a company named Olympia Film GmbH. The Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda oversaw the production of the film. Olympia prominently depicted the Nazi idea of Strength Through Joy.[2]

Joseph Goebbels discussed making the film with Leni Riefenstahl on 28 June 1935, after she received an award for Triumph of the Will. They discussed it further in August and October. Goebbels, Adolf Hitler, and Carl Diem were in agreement that Riefenstahl was the best person to direct the film. She was initially given 1.5 million ℛ︁ℳ︁, but this grew to 2.35 million ℛ︁ℳ︁.[3]

Many advanced motion picture techniques, which later became industry standards but which were groundbreaking at the time, were employed, including unusual camera angles, smash cuts, extreme close-ups and placing tracking shot rails within the bleachers. Although restricted to six camera positions on the stadium field, Riefenstahl set up cameras in as many other places as she could, including in the grandstands. She attached automatic cameras to balloons, including instructions to return the film to her, and she also placed automatic cameras in boats during practice runs. Amateur photography was used to supplement that of the professionals along the course of races. Perhaps the greatest innovation seen in Olympia was the use of an underwater camera. The camera followed divers through the air and, as soon as they hit the water, the cameraman dived down with them, all the while changing focus and aperture.[4]

Walter Frentz and Hans Ertl were among the film's camera crew.[5] Riefenstahl argued with a referee who refused to let her cameraman Gustav Lantschner film the hammer throw competition. She complained about this to Goebbels who dismissed her as a "hysterical woman" and was not allowed to return to the stadium until she apologized to the referee.[6]

Paris-soir incorrectly claimed that Goebbels slapped Riefenstahl, called her Jewish, and that she fled to Switzerland.[7]

Riefenstahl edited the film over the course of two years.[8]

Release

editThe premiere had to be postponed due to the Anschluss. Riefenstahl proposed releasing the film on Hitler's birthday.[9] Olympia was approved by the censors on 14 April 1938, and released on 20 April, Adolf Hitler's 49th birthday.[10] It had a profit of RM 114,066.45 by 1943.[11][6]

Riefenstahl toured the United States, during which she met Henry Ford and Walt Disney, in an attempt to distribute the film there. However, Kristallnacht and protests from organizations including the Jewish Labor Committee and Hollywood Anti-Nazi League doomed her efforts. Olympia was given an English-dubbed American release by Excelsior Pictures after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[12][13]

There had been few screenings of Olympia in English-speaking countries upon its original release. It was re-released in the United States in 1948 under the title Kings of the Olympics in a truncated version acquired from Germany by the U.S. Office of Alien Property Custodian and severely edited without Riefenstahl's involvement.[14] In 1955 Riefenstahl agreed to remove three minutes of Hitler footage for screening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The same version was also screened on West German television and in cinemas around the world.[15]

Reception

editThe reaction to the film in Germany was enthusiastic, and it was received with acclaim and accolades around the world.[16] In 1960, Riefenstahl's peers voted Olympia one of the 10 best films of all time. The Daily Telegraph recognised the film as "even more technically dazzling" than Triumph of the Will.[17] The Times described the film as "visually ravishing ... A number of sequences in the supposedly documentary Olympia, notably those devoted to the high-diving competition, become less and less concerned with record and more and more abstract: as some of the divers hit the water, the visual interest of patterns of movement takes over."[16]

American film critic Richard Corliss observed in Time that "the matter of Riefenstahl 'the Nazi director' is worth raising so it can be dismissed. [I]n the hallucinatory documentary Triumph of the Will ... [she] painted Adolf Hitler as a Wagnerian deity ... But that was in 1934–35. In [Olympia] Riefenstahl gave the same heroic treatment to Jesse Owens."[1]

Accolades

edit| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venice Film Festival | 31 August 1938 | Best film | Thank You, Madame | Won | [18] |

The film won several awards;[19]

- National Film Prize (1937–1938)

- Greek Sports Prize (1938)

- Olympic Gold Medal from the International Olympic Committee (1939)

- Lausanne International Film Festival (1948) — Olympic Diploma

In popular culture

edit- In the 2016 biographical film about Jesse Owens, Race, the filming at the Olympic Games is depicted with Riefenstahl constantly quarreling with Goebbels about her artistic decisions, especially over filming Jesse Owens, who is proving a politically embarrassing refutation of Nazi Germany's claims about Aryan athletic supremacy.

- Neue Deutsche Härte band Rammstein released a cover of Depeche Mode's song "Stripped" in 1998. The song's music video is made from footage from Olympia.

References

edit- ^ a b "All-Time 100 Movies". Time. 12 February 2005. Archived from the original on May 23, 2005. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Welch 1983, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Niven 2018, pp. 85, 87.

- ^ Barnouw, Erik (1993). Documentary. Oxford University Press. p. 108-109. ISBN 978-0-19-507898-5.

- ^ Waldman 2008, p. 186.

- ^ a b Niven 2018, p. 87.

- ^ Niven 2018, p. 89.

- ^ Welch 1983, pp. 93.

- ^ Niven 2018, p. 90.

- ^ Welch 1983, pp. 93, 283.

- ^ Welch 1983, pp. 98.

- ^ Waldman 2008, p. 185-186.

- ^ Stern, Frank. "Screening Politics: Cinema and Intervention". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Foreign Film and the Olympic Documentary Also Arrive at Local Theatres The New York Times. 23 April 1948

- ^ Bach, Steven (2006). Leni- The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl. Abacus.

- ^ a b Leni Riefenstahl (obituary)[dead link] The Times. 10 September 2003

- ^ Leni Riefenstahl (obituary) Daily Telegraph. 9 September 2003

- ^ Waldman 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Leni Riefenstahl Olympia Archived 2009-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

Works cited

edit- Niven, Bill (2018). Hitler and Film: The Führer's Hidden Passion. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300200362.

- Waldman, Harry (2008). Nazi Films In America, 1933-1942. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786438617.

- Welch, David (1983). Propaganda and the German Cinema: 1933-1945. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860645204.

Further reading

edit- Rossol, Nadine. "Performing the Nation: Sports, Spectacles, and Aesthetics in Germany, 1926-1936," Central European History Dec 2010, Vol. 43 Issue 4, pp 616–638

- McFee, Graham and Alan Tomlinson. "Riefenstahl's 'Olympia:' Ideology and Aesthetics in the Shaping of the Aryan Athletic Body," International Journal of the History of Sport, Feb 1999, Vol. 16 Issue 2, pp 86–106

- Mackenzie, Michael, “From Athens to Berlin: The 1936 Olympics and Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia,” in: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 29 (Winter 2003)

- Rippon, Anton. Hitler's Olympics: The Story of the 1936 Nazi Games 2006