Lahontan cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi) is the largest subspecies of cutthroat trout and the state fish of Nevada. It is one of three subspecies of cutthroat trout that are listed as federally threatened.[2][5]

| Lahontan cutthroat trout | |

|---|---|

| |

| O. clarkii henshawi, stream form | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Salmoniformes |

| Family: | Salmonidae |

| Genus: | Oncorhynchus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | O. c. henshawi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi | |

Natural history

editThe Lahontan cutthroat is native to the drainages of the Truckee River, Humboldt River, Carson River, Walker River, Quinn River, and several smaller rivers in the Great Basin of North America.[6] These were tributaries of ancient and massive Lake Lahontan during the ice ages until the lake shrank to remnants such as Pyramid Lake and Walker Lake about 7,000 years ago, although Lake Tahoe—from which the Truckee flows to Pyramid Lake—is still a large mountain lake. In this sense, Lahontan cutthroats essentially evolved in inland ocean-like conditions.

Here, Lahontan cutthroats became a large (up to 1 m or 39 in) and moderately long-lived predator of chub suckers and other fish as long as 30 or 40 cm (16 in). The trout was able to remain a predator in the larger remnant lakes where prey fish continued to flourish, but upstream populations were forced to adapt to eating smaller fish and insects. Some experts consider O. c. henshawi in the upper Humboldt River and its tributaries to be a separate subspecies, O. Clarkii Humboldtensis or the Humboldt cutthroat trout, is adapted to living in small streams rather than large lakes.[7]

The record-size cutthroat trout of any subspecies was a Lahontan caught in Pyramid Lake, weighing 41 lb (18.6 kg), although anecdotal and photographic evidence exists of even larger fish from this lake.

Human history

editThe Lahontan cutthroats of Pyramid and Walker Lakes were of considerable importance to both the Paiute tribe and the Washoe tribe of Nevada and California. These trout, as well as cui-ui (Chasmistes cujus), a sucker now found only in Pyramid Lake, were dietary mainstays and were used by other tribes in the area.[8]

When John C. Frémont and Kit Carson ascended the Truckee River on January 16, 1844, they called it the 'Salmon Trout River', after the huge Lahontan cutthroat trout that ran up the river from Pyramid Lake to spawn.[9]

American settlements in the Great Basin nearly extirpated this species. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Lahontan cutthroats were caught in tremendous numbers and shipped to towns and mining camps throughout the West; estimates have ranged as high as 1,000,000 lb (450,000 kg) annually between 1860 and 1920. A dam in Mason Valley blocked spawning runs from Walker Lake. By 1905, Derby Dam on the Truckee River below Reno interfered with Pyramid Lake's spawning runs. A poorly designed fish ladder washed away in 1907, and then badly timed water diversions to farms in the Fallon, Nevada, area stranded spawning fish and desiccated eggs below the dam. By 1943, Pyramid Lake's population was extinct. Lake Tahoe's population was extinct by 1930 from competition and inbreeding with introduced rainbow trout (creating cutbows), predation by introduced lake trout, and diseases introduced along with these exotic species.

Upstream populations have been isolated and decimated by poorly managed grazing and excessive water withdrawals for irrigation, as well as by hybridization, competition, and predation by non-native salmonids. This is important, as although Lahontan cutthroat trout can inhabit either lakes or streams, they are obligatory stream spawners.[10]

Pyramid Lake and Truckee River water quality

editPyramid Lake, the second-largest natural lake in the Western United States—prior to construction of the Derby Dam, which diverted water from the lake—has been the focus of several water quality investigations, the most detailed starting in the mid-1980s. Under the direction of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's comprehensive dynamic hydrology transport model, the Dynamic Stream Simulation and Assessment Model (DSSAM), was applied to analyze impacts of a variety of land use and wastewater management decisions throughout the 3,120-square-mile (8,100 km2) Truckee River Basin.[11] These analyses allowed more competent decisions to be made regarding the watersheds, as well as the management of treated effluent discharged to the Truckee River.

Conservation

editLahontan cutthroat trout currently occupy a small fraction of their historic range. The primary obstacle to their recovery is non-native salmonid predation by brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) on fluvial cutthroat and lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) on lacustrine cutthroat.[6] Also, hybridization of cutthroat with non-native rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) continues to threaten recovery of the pure Lahontan cutthroat. In the Truckee River and Lake Tahoe watersheds, only Independence Lake and Cascade Lake have continuously harbored the historic native lacustrine Lahontan cutthroat population.[12][13] In Independence Lake, precariously low spawner numbers have recently increased along with five years of brook trout removal.[14]

Pyramid and Walker Lakes have been restocked with fish captured in Summit Lake in Nevada and Lake Heenan in California, and those populations are maintained by fish hatcheries. Unfortunately, the Summit Lake strain does not live as long or grow as large as the original lacustrine strain of fish. However, in the 1970s, fish believed to have been stocked almost a century ago from the Pyramid Lake strain were discovered in a small stream along the Pilot Peak area of the western Utah border and are a genetic match to the original strain. This Pilot Peak strain is now integral to the reintroduction and planting programs maintained by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[15] Another strain of the subspecies from Independence Lake is available, and a broodstock is managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife at their hatchery on Hot Creek, though less is known about the suitability of Independence Lake fish to other systems.

Preservation of highly complementary habitats is crucial for the survival of the different age classes of cutthroat trout, with clean gravels needed for spawning, slow-moving side channel habitats used by juvenile fish, and deeper pool habitats such as beaver ponds for larger adult fish.[16]

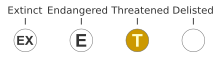

They were classified as endangered species between 1970 and 1975,[3] then the classification was changed to threatened species in 1975,[4] and reaffirmed as threatened in 2008.[10]

Although Lahontan cutthroat trout stand little chance of surviving for long in Lake Tahoe, the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW) planted them instead of rainbow trout on the lake's Nevada shore in summer 2011. The goal is to enable anglers to catch Lake Tahoe's native trout for the first time since 1939. The California state record was caught in Lake Tahoe in 1911 by William Pomin, weighing 31 lb (14 kg), 8 oz (230 g).[17]

Because it tolerates water too alkaline for other trout, Lahontan cutthroats are stocked in alkaline lakes outside its native range, including Lake Lenore (alternately Lenore Lake), Grimes Lake and Omak Lake in central Washington[18] and Mann Lake[19] in Oregon's Alvord Desert east of Steens Mountain.

References

edit- ^ NatureServe (7 April 2023). "Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Lahontan cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b 35 FR 16047

- ^ a b 40 FR 29863

- ^ "Lahontan cutthroat trout". U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Nevada Office. 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b Robert J. Behnke (1992). Native Trout of Western North America. Bethesda, Maryland: American Fisheries Society Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780913235799. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ^ Trotter, Patrick C.; Behnke, Robert J. (2008). "The case for humboldtensis: A subspecies name for the indigenous cutthroat trout, Oncorhynchus clarkii of the Humboldt River, Upper Quinn River, and Coyote Basin Drainages, Nevada and Oregon". Western North American Naturalist. 68 (1): 58–65. doi:10.3398/1527-0904(2008)68[58:TCFHAS]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 41717657.

- ^ Sigler, William F.; Sigler, John W. (1987). Fishes of the Great Basin. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780874171167. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ^ John Charles Fremont (1847). Narrative of the exploring expedition to the Rocky mountains: in the year 1842, and to Oregon and north California in the years 1843-44. Hall & Dickson. p. 309. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

salmon trout river.

- ^ a b Nevada Fish and Wildlife Office (2008-09-09). 90-Day Finding on a Petition To Delist the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (PDF) (Report). Vol. 73. Federal Register. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-17. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Marc Papineau of Earth Metrics Inc. (1987). Development of a dynamic water quality simulation model for the Truckee River (Report). Washington D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency Technology Series.

- ^ M. Jake Vander Zanden, Sudeep Chandra, Brant C. Allen, John E. Reuter, and Charles R. Goldman (2003). "Historical Food Web Structure and Restoration of Native Aquatic Communities in the Lake Tahoe (California–Nevada) Basin". Ecosystems. 6: 274–288. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mary M. Peacock, Evon R. Hekkala, Veronica S. Kirchoff, and Lisa G. Heki. "Return of a giant: DNA from archival museum samples helps to identify a unique cutthroat trout lineage formerly thought to be extinct". Royal Society Open Science. 4: 171253. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scoppettone, G. Gary; Rissler, Peter H.; Shea, Sean P.; Somer, William (2012). "Effect of Brook Trout Removal from a Spawning Stream on an Adfluvial Population of Lahontan Cutthroat Trout". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 32 (3): 586–596. doi:10.1080/02755947.2012.675958.

- ^ Mike Caltagirone (2010-01-19). "Bringing Home the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout". Blood Knot Magazine. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ White, Seth M.; Rahel, Frank J. (2008). "Complementation of Habitats for Bonneville Cutthroat Trout in Watersheds Influenced by Beavers, Livestock, and Drought". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 137 (3): 881–894. doi:10.1577/T06-207.1.

- ^ Bruce Ajari (2011-08-11). "Reintroduction of Lahontan cutthroat trout should benefit anglers". Tahoe Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ Rich Landers (11 May 2016). "Lahontans still thrive at Lake Lenore despite net poaching". Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Sheehan, Madelynne Diness (April 2005). Fishing in Oregon: The Complete Oregon Fishing Guide (10th ed.). Scappoose, Oregon: Flying Pencil Publications. pp. 282–83. ISBN 978-0-916473-15-0.

Further reading

edit- Trotter, Patrick C. (2008). Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25458-9.

External links

edit- Lahontan cutthroat trout at U.S. Fish and Wildlife Archived 2020-09-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Lahontan cutthroat trout at California Department of Fish and Game

- Nate Schweber, "Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Make a Comeback", New York Times, April 24, 2013 (20- and 25-pound trout caught and released; review of recovery efforts)