The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (Latin: Ordo Equestris Sancti Sepulcri Hierosolymitani, OESSH), also called the Order of the Holy Sepulchre or Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, is a Catholic order of knighthood under the protection of the Holy See. The Pope is the sovereign of the order. The order creates canons as well as knights, with the primary mission to "support the Christian presence in the Holy Land".[1] It is an internationally recognised order of chivalry. The order today is estimated to have some 30,000 knights and dames in 60 lieutenancies around the world.[2] The Cardinal Grand Master has been Fernando Filoni since 2019, and the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem is ex officio the Order's Grand Prior. Its headquarters are situated at the Palazzo Della Rovere and its official church in Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo, both in Rome, close to Vatican City.[3] In 1994, Pope John Paul II declared the Virgin Mary as the order's patron saint under the title "Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of Palestine".[4]

Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem | |

Ordo Equestris Sancti Sepulcri Hierosolymitani | |

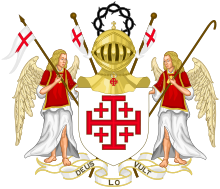

Coat of arms of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre | |

| Abbreviation | OESSH |

|---|---|

| Formation | c. 1099 |

| Founder | Godfrey of Bouillon |

| Founded at | Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

| Type | Order of chivalry |

| Purpose | Support the Christian presence in the Holy Land |

| Headquarters | Palazzo Della Rovere |

| Location |

|

Region served | Worldwide |

| Membership | 30,000 |

| Pope Francis | |

| Fernando Cardinal Filoni | |

| Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem Pierbattista Pizzaballa | |

Assessor | Tommaso Caputo |

Main organ | Council Complete of State |

Parent organization | Holy See |

| Affiliations | |

| Award(s) |

|

| Website | www |

Formerly called |

|

Name

editThe name of the knights and order varied over the centuries, including Milites Sancti Sepulcri and The Sacred and Military Order of the Holy Sepulchre. The current name was determined on 27 July 1931 as the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (with of Jerusalem as honorary suffix) by decree of the Sacred Congregation of Ceremonies of the Holy See. The term equestrian in this context is consistent with its use for orders of knighthood of the Holy See, referring to the chivalric and knightly nature of order—by sovereign prerogative conferring knighthood on recipients—derived from the equestrians (Latin: equites), a social class in Ancient Rome.

History

editThe history of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem runs common and parallel to that of the religious Canons Regular of the Holy Sepulchre, the order continuing after the Canons Regular ceased to exist at the end of the 15th century (except for their female counterpart, the Canonesses Regular of the Holy Sepulchre).

Background

editPilgrimages to the Holy Land were a common, if hazardous, practice from shortly after the crucifixion of Jesus[5] to throughout the Middle Ages. Numerous detailed commentaries have survived as evidence of this early Christian devotion.[5] While there were many places the pious visited during their travels, the one most cherished was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, first constructed by Constantine the Great in the 4th century AD.[6]

During the era of the Islamic expansion, Emperor Charlemagne (c. 742–814) sent two embassies to the caliph of Baghdad, asking Frankish protectorate over the Holy Land. An epic chanson de geste recounts his legendary adventures in the Mediterranean and pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[7]

By virtue of its defining characteristic of subinfeudation, in feudalism it was common practice for knights commanders to confer knighthoods upon their finest soldiers, who in turn had the right to confer knighthood on others upon attaining command.[8] Tradition maintains, that long before the Crusades, a form of knighthood was bestowed upon worthy men at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In any case, during the 11th century, prior to the Crusades, the "Milites Sancti Petri" were established to protect Christians and Christian premises in the Occident.[9][10]

Persecution of Christians in the Holy Land intensified and relations with Christian rulers were further strained when Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in 1009.[11]

Crusades

editThe crusades coincided with a renewed concern in Europe for the holy places, with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as one of the most important places. According to an undocumented tradition, Girolamo Gabrielli of the Italian Gabrielli family, who was the leader of 1000 knights from Gubbio, Umbria, during the First Crusade, was the first crusader to enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre after Jerusalem was seized in 1099.[12]

Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291)

editAfter the capture of Jerusalem at the end of the First Crusade in 1099, the Canons Regular of the Holy Sepulchre were established to take care of the church. The men in charge of securing its defence and its community of canons were called Milites Sancti Sepulcri.[13] Together, the canons and the milites formed part of the structure of which evolved into the modern Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem. Baldwin I, the first king of Jerusalem, laid the foundations of the kingdom and established its main institutions on the French pattern as a centralised feudal state. He also drew up the first constitution of the order in 1103, modelled on the chapter of canons that he founded in Antwerp prior to his departure, under which the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem (who had supplanted the Greek Orthodox patriarch) appointed knights in Jerusalem at the direct service of the crown, similar to the organisation of third orders. Adopting the rule of Saint Augustine, with recognition in 1113 by Papal Bull of Pope Paschal II, with the Milites Sancti Sepulcri attached, it is considered among the oldest of the chivalric orders.[14][1][15] Indications suggest that Hugues de Payens (c. 1070–1136) was among the Milites Sancti Sepulcri during his second time in Jerusalem in 1114–16, before being appointed "Magister Militum Templi", establishing the Knights Templar.[16]

Between c. 1119–c. 1125, Gerard (Latin: Girardus), the Prior of the Holy Sepulchre, along with Patriarch Warmund of Jerusalem, wrote a significant letter to Diego Gelmírez, Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela citing crop failures and being threatened by their enemies; they requested food, money, and military aid in order to maintain the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[17] Gerard consequently participated among others in the Council of Nablus, 16 January 1120. In it, Canons 20–21 deal with clerics. Canon 20 says a cleric should not be held guilty if he takes up arms in self-defense, but he cannot take up arms for any other reason nor can he act like a knight. This was an important concern for the crusader states; clerics were generally forbidden from participating in warfare in European law, but the crusaders needed all the manpower they could find and, only one year before, Antioch had been defended by the Latin patriarch of Antioch following the Battle of Ager Sanguinis, one of the calamities referred to in the introduction to the canons. Canon 21 says that a monk or canon regular who apostatizes should either return to his order or go into exile.

In 1121, Pope Callixtus II issued a bull formally erecting the Canons Regular of the Holy Sepulchre with specific responsibilities to defend the Church Universal, protect the City of Jerusalem, guard the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre and pilgrims, and fight in the defence of Christianity.[18]

In total, as a result of these military needs, five major chivalric communities were established in the Kingdom of Jerusalem between the late 11th century and the early 12th century: the Knights Hospitaller (Order of Saint John) (circa 1099), the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre (circa 1099), the Knights Templar (circa 1118), the Knights of Saint Lazarus (1123), and the Knights of the Hospital of Saint Mary of Jerusalem (Teutonic Knights) (1190).[19][20][21]

Today,

- the Order of Knights Templar no longer exists (other than its successor in Portugal – the Order of Christ),

- the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus is recognised as the successor to the medieval Order of Saint Lazarus,

- the successor to the Teutonic Order is a purely religious order of the Catholic Church,

- but both the Order of Malta and the Order of the Holy Sepulchre continue as chivalric orders recognised by the Holy See.

The Pactum Warmundi, establishing in 1123 an alliance of the Kingdom of Jerusalem with the Republic of Venice, was later signed by Patriarch Warmund and Prior Gerard of the Holy Sepulchre, along with Archbishop Ehremar of Caesarea, Bishop Bernard of Nazareth, Bishop Aschetinus of Bethlehem, Bishop Roger of Bishop of Lydda, Guildin the Abbot of St. Mary of Josaphat, Prior Aicard of the Templum Domini, Prior Arnold of Mount Zion, William Buris, and Chancellor Pagan. Aside from William and Pagan, no secular authorities witnessed the treaty, perhaps indicating that the allied Venetians considered Jerusalem a papal fief.

Meanwhile, beyond the Holy Land, in Spain, during the Reconquista, military orders built their own monasteries which also served as fortresses of defence, though otherwise the houses followed monastic premises. A typical example of this type of monastery is the Calatrava la Nueva, headquarters of the Order of Calatrava, founded by the Abbot of Fitero, Raymond, at the behest of King Sancho III of Castile, to protect the area restored to the Islamic rulers. Other orders such as the Order of Santiago, Knight Templars and the Holy Sepulchre devoted much of their efforts to protect and care for pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. Furthermore, at the Siege of Bayonne in October 1131, three years before his death, King Alfonso I of Aragon, having no children, bequeathed his kingdom to three autonomous religious orders based in the Holy Land and politically largely independent – the Knights Templars, the Knights Hospitallers and the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre – whose influences might have been expected to cancel one another out. The will has greatly puzzled historians, who have read it as a bizarre gesture of extreme piety uncharacteristic of Alfonso that effectively undid his life's work. Elena Lourie (1975) suggested instead that it was Alfonso's attempt to neutralize the papacy's interest in a disputed succession – Aragon had been a fief of the Papacy since 1068 – and to fend off his stepson, Alfonso VII of Castile, for the Papacy would be bound to press the terms of such a pious testament.[22]

In 15 July 1149 in the Holy Land, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem was consecrated after reconstruction.

Crusade vows meant that even if a person wasn't able to make the journey to Holy Sepulchre himself, sometimes his cloak was taken there, as was the case with King Henry the Young of England (1155–1183). Robert the Bruce and James Douglas, Lord of Douglas even asked to have their hearts taken to the Holy Sepulchre after death.

I will that as soone as I am trespassed out of this worlde that ye take my harte owte of my body, and embawme it, and take of my treasoure as ye shall thynke sufficient for that enterprise, both for your selfe and suche company as ye wyll take with you, and present my hart to the holy Sepulchre where as our Lorde laye, seyng my body can nat come there.

Besides pilgrimages and the creation of knights, even coronations took place at the Holy Sepulchre. Shortly before his death in 1185, Baldwin IV ordered a formal crown-wearing by his nephew, Baldwin V, at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The official arrival of the Franciscan Friars Minor in Syria dates from the papal bull addressed by Pope Gregory IX to the clergy of the Holy Land in 1230, charging them to welcome the Friars Minor, and to allow them to preach to the faithful and hold oratories and cemeteries of their own. In the ten years' truce of 1229 concluded between King Frederick of Sicily and the Sultan Al-Kamil, the Franciscans were permitted to enter Jerusalem, but they were also the first victims of the violent invasion of the Khwarezmians in 1244.

Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land (1291–1489)

editThe ultimate fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to the Muslims in 1291 did not suspend pilgrimages to the tomb of Christ or the custom of receiving knighthood there, and when the Custody of the Holy Land was entrusted to the Franciscan Order they continued this pious custom and gave the order its first grand master after the death of the last king of Jerusalem.[24]

The friars quickly resumed possession of their convent of Mount Zion at Jerusalem. The Turks tolerated the veneration paid to the tomb of Christ and derived revenue from the taxes levied upon pilgrims. In 1342, in his bull Gratiam agimus, Pope Clement VI officially committed the care of the Holy Land to the Franciscans;[25] only the restoration of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem by Pius IX in 1847 superseded the Franciscans.[26]

With the emergence of the code of conduct of chivalry during the Middle Ages, conferring of knighthoods was pursued also at the Holy Sepulchre. From the period 1291 to 1847, the Franciscan Custodian of Mount Sion was the only authority representing the Holy See in the Holy Land.[27]

Documented from 1335, the Franciscan Custody enrolled applicants as Knights of the Holy Sepulchre in ceremonies frequently mentioned in the itineraries of pilgrims. Those pilgrims deemed worthy received the honour in a solemn ceremony of ancient chivalry. However, in the ceremonial of reception at the time, the role of the clergy was limited to the benedictio militis, the dubbing with the sword being reserved to a professional knight, since the carrying of the sword was incompatible with the sacerdotal character, and reserved to previous knights.

Post misam feci duos milites nobiles supra selpulchram gladios accingendo et alia observando, quae in professione militaris ordinis fieri consueverunt. |

After Mass, I made two [of my companions] noble knights of the Sepulchre by girding them with swords and by observing those other things, which in the profession of the knightly order have been accustomed to be done.[28] |

| —Wilhelm von Boldensele (c. 1285–1338) |

In 1346, King Valdemar IV of Denmark went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and was made a knight of the Holy Sepulchre. This increased the prestige of Valdemar, who had difficulty in effectively ruling over his kingdom.[29] Saint Bridget of Sweden, one of the future patron saints of Europe, made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1371–1373 along with her sons. The oldest, Karl, died prior in Naples, but Birger Ulfsson became a knight of the Holy Sepulchre, followed by Hugo von Montfort (1395) and more to come.

Duke Albert IV of Austria was made a knight in 1400, followed by his brother Ernest (1414) and by the Kalmar ruler Eric of Pomerania (1420's) and later by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III (1436), accompanied by Georg von Ehingen and numerous other knighted nobles; later were Count Otto II of Mosbach-Neumarkt (1460), Landgrave William III of Thuringia (1461) and Heinrich Reuß von Plauen (1461) who was also grand master of the Teutonic Order.[30]

The significance of the pilgrimages is indicated by various commemorations of the knights. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre of Görlitz in Saxony was built by Georg Emmerich, who was knighted in 1465. Of the medieval Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, notably, Emmerich, although a mayor and a wealthy merchant, was neither a monarch nor a nobleman. Eberhard I of Württemberg, knighted together with Christoph I of Baden in 1468, chose a palm as his personal symbol, including in the crest (heraldry) of his coat of arms. Others built church buildings in their hometowns, such as the chapel in Pratteln, Switzerland, by Hans Bernhard von Eptingen (knighted 1460),[31] and Jeruzalemkerk in Bruges, Belgium, built by Anselm Adornes (knighted 1470). The latter still stands to this day, modelled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and today adorned with the heraldry of the order.

Some property of the Knights in Italy was transferred to the newly established Order of Our Lady of Bethlehem in 1459, but the merger proved a failure.[32] The Order of Our Lady of Bethlehem was suppressed almost as soon as it was founded and those orders whose goods the pope had transmitted to it were re-established.[33][34]

The accolades continued: Counts Enno I and Edzard I of East Frisia (1489), followed by Elector Frederick III of Saxony (1493) who was also recipient of the papal honour of the Golden Rose, together with Christoph the Strong of Bavaria,[35] then Frederick II of Legnica (1507),[36] and others.

Franciscan Grand Magistry

editFrom 1480 to 1495, John of Prussia, a Knight of the Holy Sepulchre, acted as Steward for the Convent and regularly discharged the act of accolade. It was a frequent occurrence that a foreign Knight present among the crowds of pilgrims would assist at this ceremony. However, without other assistance, it was the Superior who had to act instead of a Knight, although such a course was deemed irregular. Around this time, the Superior of the Convent assumed the title of Grand Master of the Knights, a title acknowledged by various pontifical diplomas.

When the Canons Regular of the Holy Sepulchre were suppressed in 1489, Pope Innocent VIII attempted to merge the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre into the Knights Hospitaller, but this was not successful. The Franciscan province of the Holy Land continued to exist, with Acre as its seat. In the territory of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, reinstituted in 1847, the Franciscans still have 24 convents, and 15 parishes.[37]

Papal Grand Magistry (1496–1847)

editIn 1496, Pope Alexander VI restored the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre to independent status, organised as an Order. He decreed that the Knights would no longer be governed by the Custody of the Holy Land, but that the senior post of the Order would henceforth be raised to the rank of Grand Master, reserving this title for himself and his successors.[38]

The prerogative of dubbing Knights of the Holy Sepulchre was repeatedly confirmed by the Holy See; by Pope Leo X on 4 May 1515, by Pope Clement VII in 1527 and by Pope Pius IV on 1 August 1561.

The privileges of the order, recorded by its guardian in 1553 and approved by successive popes, included powers to:[27]

- Legitimise bastards

- Change a name given in baptism

- Pardon prisoners they might meet on the way to the scaffold

- Possess goods belonging to the Church even though they were laymen

- Be exempt from taxes

- Cut a man down from the gallows and to order him to be given a Christian burial

- Wear brocaded silk garments

- Enter a church on horseback

- Fight against the infidel

In France, King Henry IV of France purchased its French possessions and incorporated them into his newly established Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, formally established by Pope Paul V through the bull Romanus Pontificus on 16 February 1608 and expanded through Militantium ordinum dated 26 February 1608, along with possessions of other orders which apparently were all deemed extinct and abolished, indicating reduced regional activity.[39]

Nonetheless, the dubbing and the privileges enjoyed continued confirmation, by Pope Alexander VII on 3 August 1665, by Pope Benedict XIII on 3 March 1727,[40] and by Pope Benedict XIV (1675–1758) who approved all but the last of the privileges of the order, and also stated that it should enjoy precedence over all orders except the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Pontifical Orders.

Knights of the Holy Sepulchre dubbed during this era include Hieronymus von Dorne (circa 1634) and François-René de Chateaubriand (1806).

Restoration of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem (1847)

editPius IX re-established the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem in 1847, and re-organized the Order of the Holy Sepulchre as the Milites Sancti Sepulcri, whereby the grand master of the order was to be the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, and the order ceased to be a pontifical order for a period. Initially, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta opposed the decision and claimed rights to its legacy, probably based on the papal decision of 1489. However, in 1868 it was named Equestris Ordo Sancti Sepulcri Hierosolymitani (Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem).

Pope Pius X assumed the title of grand master for the papacy again in 1907, but in 1928 this was again relinquished by Pope Pius XI in favour of the patriarch of Jerusalem, and for a time the order again ceased to be a papal order.

In 1932, Pius XI approved a new constitution and permitted investiture in the places of origin and not only in Jerusalem.[41]

Protection of the Holy See (from 1945)

editIn 1945, Pope Pius XII placed the order again under the sovereignty, patronage and protection of the Holy See, and in 1949 he approved a new constitution for the order, which included that the grand master be a cardinal of the Roman Curia, and that the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem be the Grand Prior of the order. In 1962 the Constitution of the Order was again reformed and the order was recognized as a juridical person in canon law.

The current Constitution of the Order was approved by Pope Paul VI in 1977, and it maintains those arrangements. The order's status was further enhanced by Pope John Paul II in 1996, when, in addition to its canonical legal personality, it was given civil legal personality in Vatican City State, where it is headquartered. An amendment to the Constitution of the Order was approved by Pope John Paul II simultaneously with the concession of Vatican legal personality for the order.[1]

Organisation

editThe order today remains an order of chivalry and is an association of the faithful with a legal canonical and public personality, constituted by the Holy See under Canon Law 312, paragraph 1:1,[1] represented by 60 lieutenancies in more than 40 countries around the world: 24 in Europe, 15 in the United States and Canada, 5 in Latin America and 6 in Australia and Asia.[2] It is recognised internationally as a legitimate order of knighthood, headquartered in Vatican City State under papal sovereignty and having the protection of the Holy See.

Purpose and activities

editIts principal mission is to reinforce the practice of Christian life by its members in absolute fidelity to the pope; to sustain and assist the religious, spiritual, charitable and social works and rights of the Catholic Church and the Christians in the Holy Land, particularly of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem which receives some 10 million dollars annually in donations from members of the order.[42] Other activities around the world are connected to their original functions.

Regional activities include participation in local processions and religious ceremonies, such as during Holy Week.

In France, the French Revolution resulted in a ban on conserving relics and all other sacred symbols linked to the monarchy, though pieces judged to be of high artistic quality were exempt. These relics were handed over to the archbishop of Paris in 1804 and are still held in the cathedral treasury of Notre Dame de Paris, cared for by the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre and the cathedral chapter. On the first Friday of every month at 3:00 pm, guarded by the Knights, the Relics of Sainte-Chapelle are exposed for veneration and adoration by the faithful before the cathedral's high altar.[43] Every Good Friday, this adoration lasts all day, punctuated by the liturgical offices. An exhibition entitled Le trésor de la Sainte-Chapelle was mounted at the Louvre in 2001.

Grand Masters and Grand Magisterium

editIn 1496, Pope Alexander VI vested the office of Grand Master in the papacy where it remained until 1949.[3] Since 1949, cardinals have held the office. The incumbent Cardinal Grand Master has been Fernando Filoni since 2019.

The Grand Magisterium also includes:

- Pierbattista Pizzaballa, Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem and Cardinal-Priest of Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo, Grand Prior of the Order[44]

- Tommaso Caputo, Prelate of the Territorial Prelature of Pompei, Assessor of the Order[44]

- Count Leonardo Visconti di Modrone, Governor General[44]

- P. Thomas Pogge, Vice-Governor General for North America[44]

- Jean-Pierre Glutz-Ruchti, Vice-Governor General for Europe[44]

- John Secker, Vice-Governor General for Asia and the Pacific region[44]

- Enric Mas, Vice-Governor General for Latin America[44]

- Alfredo Bastianelli, Chancellor of the Order

- Adriano Paccanelli, Master of Ceremonies of the Order[45]

- Severio Petrillo, Treasurer of the Order[45]

- Antonio Franco, Assessor of Honour[45]

- Giuseppe Lazzarotto, Assessor of Honour[45]

The offices of the Grand Magisterium are in the headquarters in Rome.[46]

Headquarters

editIts headquarters are situated at the Palazzo Della Rovere in Rome, the 15th-century palace of Pope Julius II, immediately adjacent to the Vatican on the Via della Conciliazione. It was given to the order by Pope Pius XII.[3] Its official church is the Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo in Rome, also given to the order by Pius XII.[3] In 1307, after the suppression of the Knights Templars, the Canons Regular of the Holy Sepulchre, whose main priory was at San Luca, acquired the complex of San Manno. Francesco della Rovere, the future Pope Sixtus IV, was Arch-Prior there 1460–1471.[47]

Insignia

editHeraldry

editBy ancient tradition, the order uses the arms attributed to the Kingdom of Jerusalem – a gold Jerusalem Cross on a silver/white background – but enamelled with red, the colour of blood, to signify the five wounds of Christ.[48] Prior use of the symbol is in the 1573 Constitution of the Order. Conrad Grünenberg already shows a red Jerusalem cross (with the central cross as cross crosslet rather than cross potent) as the emblem of the order in his 1486 travelogue.

Above the shield of the armorial bearings is a sovereign's gold helmet upon which are a crown of thorns and a terrestrial globe surmounted by a cross, flanked by two white standards bearing a red Jerusalem cross. The supporters are two angels wearing dalmatic tunics of red, the one on the dexter bearing a crusader flag, and the one on the sinister bearing a pilgrim's staff and shell: representing the military/crusading and pilgrim natures of the order.

The motto is Deus lo Vult ("God Wills It"). The seal of the order is in the shape of an almond and portrays, within a frame of a crown of thorns, a representation of Christ rising from the Sepulchre.

The Order of the Holy Sepulchre and the Sovereign Military Order of Malta are the only two institutions whose insignia may be displayed in a clerical coat of arms.[49]

| Heraldic representation in coat of arms of members of the order | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Cardinal Grand Master Arms are quartered with those of the Order |

bear a chief of the Order |

Arms are impaled by those of the Order |

Arms are placed on the cross of the Order (not transmissible) |

Vestments

editThe order has a predominantly white-coloured levée dress court uniform, and a more modern, military-style uniform, both of which are now only occasionally used in some jurisdictions. Pope Pius X ordained that the usual modern choir (i.e. church) dress of knights be the order's cape or mantle: a "white cloak with the cross of Jerusalem in red", as worn by the original knights.[50] Female members wear a black cape with a red Jerusalem cross bordered with gold.

The choir vestments of Canons of the Holy Sepulchre include a black cassock with magenta piping, magenta fascia, and a white mozetta with the red Jerusalem cross.

Membership

editThe order today is estimated to have some 30,000 knights and dames in 60 Lieutenancies around the world, including monarchs, crown princes and their consorts, and heads of state from countries such as Spain, Belgium, Monaco, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein.[2][42]

Membership of the order is by invitation only, to practicing Catholic men and women – laity and clergy – of good character, minimum 25 years of age,[42] who have distinguished themselves by concern for the Christians of the Holy Land. Aspirant members must be recommended by their local bishop with the support of several members of the order, and are required to make a generous donation as a "passage fee", echoing the ancient practice of crusaders paying their passage to the Holy Land, as well as an annual financial offering for works undertaken in the Holy Land, particularly in the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, throughout their life. There is a provision for the grand master to admit members by motu proprio in exceptional circumstances and also for the officers of the Grand Magistery to occasionally recommend candidates to the grand master.[51]

The honour of knighthood and any subsequent promotions are conferred by the Holy See – through diploma sealed and signed by the assessor for general affairs of the Secretariat of State in Rome as well as the cardinal grand master – which approves each person, in the name of and by the authority of the pope. The candidate is then knighted or promoted in a solemn ceremony with a cardinal or major prelate presiding.[52]

Knights and dames of the order may not join, or attend the events of, any other order that is not recognised by the Holy See or by a sovereign state, and must renounce any membership in such organisations before being appointed a knight or dame of the Holy Sepulchre. Knights and dames may be expelled from the order in circumstances where they breach its code of conduct.[52]

Ranks

editThere are several grades of knighthood. These are open to both men and women. While laity may be promoted to any rank, the ranks of the clergy are as follows: cardinals are knights grand cross, bishops are commanders with star, and priests and transitional deacons start with the rank of knight but may be promoted to commander. Permanent deacons are treated the same as the lay knights. Female members may wear chest ribbons rather than neck crosses, and the military trophies in insignia and heraldic additaments are replaced by bows.

| Rank insignia (knights) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heraldry (Knights) | ||||

| In the above depictions, the cross behind the shield should only be borne by archbishops, bishops, prelates and those with a title of nobility. | ||||

| Ribbons by rank | ||||

Below are shown the official titles of the ranks in English[53] (Italian, French, German, Spanish):[54]

- Knight / Dame of the Collar

(Cavaliere/Dama di Collare, Chevalier/Dame de Collier, Kollar-Ritter/-Dame, Caballero/Dama de Collar) - Knight / Dame Grand Cross (KGCHS / DGCHS)[55]

(Cavaliere/Dama di Gran Croce, Chevalier/Dame de Grand Croix, Großkreuz-Ritter/-Dame, Caballero/Dama de Gran Cruz) - Knight Commander with Star / Dame Commander with Star (KC*HS / DC*HS)

(Grand'Ufficiale, Grand Officier, Großoffizier, Commendator Grand Oficiale)

(Dama di Commenda con placca, Dame de Commande avec plaque, Komtur-Dame mit Stern, Dama de Encomenienda con Placa) - Knight / Dame Commander (KCHS / DCHS)

(Commendatore, Commandeur, Komtur, Comendator)

(Dama di Commenda, Dame de Commande, Komtur-Dame, Dama di Ecomendienda) - Knight / Dame (KHS / DHS)

(Cavaliere/Dama, Chevalier/Dame, Ordensritter/Dame, Caballero/Dama)

In English, a female member of this order is sometimes called "lady" in reaction to the US slang use of the term "dame" to refer to any woman. However, in accordance with standard chivalric practice in English, female members are called "dame" (from the Latin title Domina, Italian Dama, etc.) and this is the usual practice in most lieutenancies.[a]

Canons

editIn accordance with the origins of the order, and considered more consistent with ordained ministry than the military title of knight, invested clergy are ipso facto Titular Canons of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, though Grand Master John Patrick Foley argued that this would be better applied to clergy with the rank of commander.[56] Additionally, deacons, priests and bishops may also be given the distinguished honorary title of canon of the Holy Sepulchre personally by the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem.[57] Both titular canons of the Holy Sepulchre (EOHSJ) and Honorary Canons of the Holy Sepulchre of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem are entitled to identical insignia, i.e. white mozetta with red Jerusalem cross and choir dress including the black cassock with magenta piping and magenta fascia.[58]

Saints and beatified members

edit- Saint Contardo of Este (1216 - 16 April 1249)

- Pope St Pius X (2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914)

- Blessed Giuseppe Benedetto Dusmet (15 August 1818 – 4 April 1894)

- Blessed Andrea Carlo Ferrari (13 August 1850 – 2 February 1921)

- Blessed Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster (18 January 1880 – 30 August 1954)

- Blessed Bartolo Longo[59] (10 February 1841 – 5 October 1926)

- Blessed Aloysius Viktor Stepinac (8 May 1898 – 10 February 1960)

Awards and distinctions

editReserved to members, the Palm of Jerusalem is the decoration of distinction, in three classes. Additionally, knights and dames who made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land receive the Pilgrim Shell, a reference to the shells used as a cup by the pilgrims in the Middle Ages.[60] Both of these distinctions were created in 1949.[61][b] They are generally awarded by the grand prior of the order, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem.[61]

| Awards of Special Distinction | |||

Since 1949, the Cross of Merit of the Order may also be conferred on meritorious non-members of the order, for example non-Catholics.[62] The original five classes were reduced to three in 1977.[62] Obtaining the Cross of Merit does not imply membership of the Order.[62]

| Decorations of Merit | ||

Although it shares the same symbol, the Jerusalem Pilgrim's Cross is not a decoration of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre. Pope Leo XIII created the award in 1901 but the Franciscan custodian of the Holy Land presents it to certain pilgrims in the name of the pope.[63]

Gallery

edit-

Entrance of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

-

Flag of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre over the Palazzo della Rovere.

-

The convent of Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo contains the official church of the order.

-

Notre Dame de Paris in France, where the Relics of Sainte-Chapelle are exposed by the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre.

-

Inside Dresden Cathedral, 9 October 2010.

-

Procession in honour of Saint Liborius of Le Mans with Knights of the Holy Sepulchre together with Teutonic Knights in Paderborn, Germany.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Dame" is the usual English title of a female member of an order of chivalry; a "lady" in terms of orders of chivalry is usually the wife of a member although there are exceptions: for example female members of the British Order of the Garter may be called either "Lady (Royal and/or Supernumerary) Companion" (but not simply "Lady") or "Knight (Royal and/or Supernumerary) Companion". There is no provision in the constitution to use other titles in English, such as "sir", for knights although this is occasionally used. In some English-speaking lieutenancies, and consistent with the constitution and diplomatic practice of using French, a knight is addressed as chevalier, abbreviated Chev. The Diploma of Investiture of the Order, written in Latin, uses the term "Equitem" and the corresponding certificate for the Pilgrim Shell uses the Latin title "Dominum".

- ^ Bander van Duren wrongly states that they were introduced in 1977: Bander van Duren (1987). The Cross on the Sword. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe Limited. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-905715-32-2.

Citations

edit- ^ a b c d "History - Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem".

- ^ a b c "About us". Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "History". Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Blessed Vergin Mary Queen of Palestine". www.oessh.va. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Pilgrimages to the Holy Land and Communities in the Holy Land | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Evidence of Earliest Christian Pilgrimage to the Holy Land Comes to Light in Holy Sepulchre Church". The BAS Library. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Shepard, W. P. (1921). "Chansons de Geste and the Homeric Problem". The American Journal of Philology. 42 (3): 193–233. doi:10.2307/289581. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 289581.

- ^ Gautier, Léon (1891). Chivalry. Translated by Frith, Henry. Glasgow: G. Routledge and Sons. p. 223. ISBN 9780517686355. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

Every knight has the power to create knights

- ^ Mastnak, Tomaž (2002). "From Holy Peace to Holy War". Crusading Peace: Christendom, the Muslim World, and Western Political Order. University of California Press. pp. 1–54. doi:10.1525/california/9780520226357.003.0001. ISBN 978-0-520-22635-7. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Bachrach, David Stewart (2015). ""Milites" and Warfare in Pre-Crusade Germany". War in History. 22 (3): 298–343. doi:10.1177/0968344514524938. ISSN 0968-3445. JSTOR 26098395. S2CID 159106757.

- ^ Lev (1995), pp. 203, 205–208

- ^ McCracken, Laura (1905). Gubbio, Past & Present. D. Nutt. p. 26.

- ^ "Histoire du monde.net".

- ^ "History of the order form the Western Australia Lieutenancy website". Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Origins". Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Alain Demurger, The Knights Templar, a Christian chivalry in the Middle Ages, Paris, Seuil, coll. "Points History"2008(1 st ed. 2005), pocket, 664 p. 26 (ISBN 978-2-7578-1122-1)

- ^ Malcolm Barber, A. K. Bate, Letters from the East: Crusaders, Pilgrims and Settlers in the 12th–13th Centuries (Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010), p. 43

- ^ Smet, Joachim (2020). "The Latin Religious Houses in Crusader Palestine: An Inventory". Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3960485.

- ^ "Crusades - Holy War, Jerusalem, Reconquest | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Borowski, Tomasz; Gerrard, Christopher (2017). "Constructing Identity in the Middle Ages: Relics, Religiosity, and the Military Orders". Speculum. 92 (4): 1056–1100. doi:10.1086/693395. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 26583619. S2CID 164251969.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (13 March 1994). "Chivalry Is Not Dead (Published 1994)". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Pope Innocent II indeed did write Alfonso VII to just this effect, 10 June 1135 or 36 (Lourie 1995:645).

- ^ from Froissart's Chronicles, translated by John Bourchier, Lord Berners (1467–1533), E M Brougham, News Out Of Scotland, London 1926

- ^ "History - Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Armstrong, Megan C., ed. (2021), "The Order of the Holy Sepulcher", The Holy Land and the Early Modern Reinvention of Catholicism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 121–181, doi:10.1017/9781108957946.004, ISBN 978-1-108-83247-2, S2CID 238052679, retrieved 31 January 2024

- ^ Rioli, Maria Chiara (14 August 2020), "Nostalgia for an Invented Past and Concern for the Future: the Latin Diocese of Jerusalem from Its Reestablishment to the Second World War (1847–1945)", A Liminal Church, Brill, pp. 24–29, doi:10.1163/9789004423718_003, ISBN 978-90-04-42371-8, retrieved 31 January 2024

- ^ a b Peter Bander van Duren, Orders of Knighthood and of Merit

- ^ Meindl, Maria Christine. "Wenn einer eine Reise tut, dann kann er was erzählen." (Matthias Claudius) das Heilige Land in spätmittelalterlichen Reiseberichten (Master of Philosophy thesis). p. 22. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Janus Møller Jensen. Denmark and the Crusades. 2007 p.41

- ^ Johann Georg Kohl: Pilgerfahrt des Landgrafen Wilhelm des Tapferen von Thüringen zum heiligen Lande im Jahre 1461, Müller 1868, page 70

- ^ "Geschichtsquellen: Werk/2208". www.geschichtsquellen.de. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgegeben von J. S. Ersch und J. G. Gruber, J. f. Gleditsch, 1828, S. 158 f.

- ^ Besse, Jean. "Bethlehemites." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 23 June 2015

- ^ Trollope, Thomas Anthony (2 December 1834). "An encyclopædia ecclesiastica; or, A complete history of the Church" – via Google Books.

- ^ Georg Spalatin, Christian Gotthold Neudecker, Ludwig Preller: Historischer nachlass und briefe, 1851, page 89

- ^ Jan Harasimowicz: Adel in Schlesien 01: Herrschaft- Kultur- Selbstdarstellung, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag 2009, ISBN 348658877X, S. 177

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Order of Friars Minor".

- ^ "Official website of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012.

- ^ Carlisle, Nicholas (2 December 1839). "A Concise Account of the Several Foreign Orders of Knighthood, and Other Marks of Honourable Distinctions, Especially of Such as Have Been Conferred Upon British Subjects, Together with the Names and Achievements of Those Galant Men, who Have Been Presented with Honorary Swords Or Plate, by the Patriotic Fund Institution". John Hearne – via Google Books.

- ^ H. Schulze: Chronik sämmtlicher bekannten Ritter-Orden und Ehrenzeichen, welche von Souverainen und Regierungen verliehen werden, nebst Abb. der Decorationen. Moeser 1855, S. 566 f.

- ^ "How has the Order of the Holy Sepulchre evolved over time?". Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b c oessh.no

- ^ "Accueil - Notre Dame de Paris". Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Grand Magisterium of the Order - Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Grand Magisterium of the Order - Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Il Gran Magistero dell'Ordine Equestre del Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme".

- ^ "Key to Umbria: Perugia". Key to Umbria. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Constitution" (PDF). EOHSJ ~ Southwestern USA. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Acta Apostolicae Sedis, 20 April 1915, extending and clarifying the Apostolic Constitution Militantis Ecclesiae of Innocent X, 19 December 1644, cited in "A Decree on Ecclesiastical Heraldry". The Ecclesiastical Review. 53: 75 (Latin), 82–83 (English). July 1915. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ "EOHSJ — Ceremonial Dress".

- ^ "Almanach de la Cour". Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Constitution". www.oessh.va. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Ranks in the Order of the Holy Sepulchre - official website of the OESSH

- ^ "Congregazione per l'Educazione Cattolica".

- ^ "Members of the Order". EOHSJ Toronto. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Canon 1898, Ordo S. Sepulchre, Romae,1894.

- ^ "New honorary Canon of the Holy Sepulchre in Brescia". 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Barbiconi Sartoria ecclesiastica".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Saints of the Order – Middle Atlantic Lieutenancy". www.midatlanticeohs.com. Washington, D.C.: Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem. 2023. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "scallop - bivalve". 20 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Palme von Jerusalem [Palma Hierosolymitani]". Künker Münzauktionen und Goldhandel (in German). Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Bander van Duren (1987). The Cross on the Sword. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe Limited. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-905715-32-2.

- ^ "The Decoration created by Leon XIII". Custodia Terrae Sanctae. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

Sources

edit- Blasco, Alfred J. (1998). The Modern Crusaders. PenRose. ISBN 0-9632687-7-5.

- Noonan, James Charles Jr. (1996). The Church Visible: The Ceremonial Life and Protocol of the Roman Catholic Church. Viking. p. 196. ISBN 0-670-86745-4.

- Noonan, Jr., James-Charles (2012). The Church Visible: The Ceremonial Life and Protocol of the Roman Catholic Church Revised Edition. Sterling-Ethos. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4027-8730-0.

- Bander van Duren, Peter Orders of Knighthood and of Merit

- Sainty, Guy Stair. Order of the Holy Sepulchre The Order of the Holy Sepulcher

- Sainty, G. 2006. Order of the Holy Sepulchre. World Orders of Knighthood & Merit. Guy Stair Sainty (editor) and Rafal Heydel-Mankoo (deputy editor). United Kingdom: Burke's Peerage & Gentry. 2 Vol. (2100 pp).

Further reading

edit- De perenni Cultu Terra Sancta (1555), Venice 1572, by Boniface of Ragusa

- Liber De perenni Cultu Terrae Sanctae Et De Fructuosa eius Peregrinatione, Venice 1573, by Boniface of Ragusa

- Discours du voyage d'Outre Mer au Sainct Sépulcre de Iérusalem, et autres lieux de la terre Saincte, Lyon 1573, by Antoine Régnault

- Csordás Eörs, editor, Miles Christi, Budapest: Szent István Társulat, 2001, 963361189X