This article needs to be updated. (July 2014) |

Psittacosis—also known as parrot fever, and ornithosis—is a zoonotic infectious disease in humans caused by a bacterium called Chlamydia psittaci and contracted from infected parrots, such as macaws, cockatiels, and budgerigars, and from pigeons, sparrows, ducks, hens, gulls and many other species of birds. The incidence of infection in canaries and finches is believed to be lower than in psittacine birds.

| Psittacosis | |

|---|---|

| |

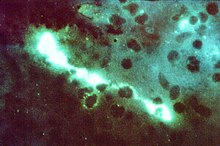

| Direct fluorescent antibody stain of a mouse brain impression smear showing C. psittaci | |

| Specialty | Infectious medicine Pulmonology |

In certain contexts, the word is used when the disease is carried by any species of birds belonging to the family Psittacidae, whereas ornithosis is used when other birds carry the disease.[1]

In humans

editSigns and symptoms

editIn humans, after an incubation period of 5–19 days, the disease course ranges from asymptomatic to systemic illness with severe pneumonia. It presents chiefly as an atypical pneumonia. In the first week of psittacosis, the symptoms mimic typhoid fever, causing high fevers, joint pain, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, nose bleeds, and low level of white blood cells.[2] Rose spots called Horder's spots sometimes appear during this stage.[3][4] These are pink, blanching maculopapular eruptions resembling the rose spots of typhoid fever.[5] Spleen enlargement is common towards the end of the first week, after which psittacosis may develop into a serious lung infection. Diagnosis is indicated where respiratory infection occurs simultaneously with splenomegaly and/or epistaxis. Headache can be so severe that it suggests meningitis and some nuchal rigidity is not unusual. Towards the end of the first week, stupor or even coma can result in severe cases.[citation needed]

The second week is more akin to acute bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia with continuous high fevers, headaches, cough, and dyspnea. X-rays at that stage show patchy infiltrates or a diffuse whiteout of lung fields.[citation needed]

Complications in the form of endocarditis, liver inflammation, inflammation of the heart's muscle, joint inflammation, keratoconjunctivitis (occasionally extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the lacrimal gland/orbit)[citation needed], and neurologic complications (brain inflammation) may occasionally occur. Severe pneumonia requiring intensive-care support may also occur. Fatal cases have been reported (less than 1% of cases).[citation needed]

Transmission route

editThe Chlamydia psittaci bacterium that causes psittacosis can be transmitted by mouth-to-beak contact, or through the airborne inhalation of feather dust, dried faeces, or the respiratory secretions of infected birds.[6] Person-to-person transmission is possible, but rare.[6]

Diagnosis

editBlood analysis usually shows a normal white cell count, but marked leukocytosis is occasionally apparent. Liver enzymes are abnormal in half of the patients, with mild elevation of aspartate transaminase. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein can be markedly elevated. Differential diagnosis must be made with typhus, typhoid, and atypical pneumonia by Mycoplasma, Legionella, or Q fever. Exposure history is paramount to diagnosis. Diagnosis involves microbiological cultures from respiratory secretions of patients or serologically with a fourfold or greater increase in antibody titers against C. psittaci in blood samples combined with the probable course of the disease. Typical inclusions called "Leventhal-Cole-Lillie bodies"[7] can be seen within macrophages in BAL (bronchoalveolar lavage) fluid. Culture of C. psittaci is hazardous and should only be carried out in biosafety laboratories.[citation needed]

Treatment

editThe infection is treated with antibiotics; tetracyclines and chloramphenicol are the choice for treating patients.[8] Most people respond to oral therapy doxycycline, tetracycline hydrochloride, or chloramphenicol palmitate. For initial treatment of severely ill patients, doxycycline hyclate may be administered intravenously. Remission of symptoms is usually evident within 48–72 hours. However, relapse can occur, and treatment must continue for at least 10–14 days after fever subsides.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

editPsittacosis was first reported in Europe in 1879.[9]

In 1929, a highly publicized outbreak of psittacosis hit the United States. Although not the first report of psittacosis in the United States, it was the largest up to that time. It led to greater controls on the import of pet parrots.[9] The aftermath of the outbreak and how it was handled led to the establishment of the National Institutes of Health.[10]

From 2002 through 2009, 66 human cases of psittacosis were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[citation needed] and most resulted from exposure to infected pet birds, usually cockatiels, parakeets, and macaws. Many more cases may occur that are not correctly diagnosed or reported. Bird owners, pet shop employees, zookeepers, and veterinarians are at risk of the infection. Some outbreaks of psittacosis in poultry-processing plants have been reported.

In birds

editIn birds, Chlamydia psittaci infection is referred to as avian chlamydiosis. Infected birds shed the bacteria through feces and nasal discharges, which can remain infectious for several months. Many strains remain quiescent in birds until activated under stress. Birds are excellent, highly mobile vectors for the distribution of chlamydial infection because they feed on, and have access to, the detritus of infected animals of all sorts.

Signs

editC. psittaci in birds is often systemic and infections can be inapparent, severe, acute, or chronic with intermittent shedding. Signs in birds include "inflamed eyes, difficulty in breathing, watery droppings, and green urates."[11]

Diagnosis

editInitial diagnosis may be by symptoms, but is usually confirmed by an antigen and antibody test. A polymerase chain reaction-based test is also available. Although any of these tests can confirm psittacosis, false negatives are possible, so a combination of clinical and laboratory tests is recommended before giving the bird a clean bill of health.[11]

Epidemiology

editInfection is usually by the droppings of another infected bird, though it can also be transmitted by feathers and eggs,[12] and is typically either inhaled or ingested.[11]

C. psittaci strains in birds infect mucosal epithelial cells and macrophages of the respiratory tract. Septicaemia eventually develops and the bacteria become localized in epithelial cells and macrophages of most organs, conjunctiva, and gastrointestinal tract. It can also be passed in the eggs. Stress commonly triggers onset of severe symptoms, resulting in rapid deterioration and death. C. psittaci strains are similar in virulence, grow readily in cell culture, have 16S-rRNA genes that differ by <0.8%, and belong to eight known serovars. All should be considered to be readily transmissible to humans.[citation needed]

C. psittaci serovar A is endemic among psittacine birds and has caused sporadic zoonotic disease in humans, other mammals, and tortoises. Serovar B is endemic among pigeons, has been isolated from turkeys, and has also been identified as the cause of abortion in a dairy herd. Serovars C and D are occupational hazards for slaughterhouse workers and for people in contact with birds. Serovar E isolates (known as Cal-10, MP, or MN) have been obtained from a variety of avian hosts worldwide, and although they were associated with the 1920s–1930s outbreak in humans, a specific reservoir for serovar E has not been identified. The M56 and WC serovars were isolated during outbreaks in mammals.

Treatment

editTreatment is usually with antibiotics, such as doxycycline or tetracycline, and can be administered through drops in the water or injections.[12] Many strains of C. psittaci are susceptible to bacteriophages.[citation needed]

Use as a biological weapon

editPsittacosis was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program.[13]

Notable casualties

editIn 1930, during the 1929–1930 psittacosis pandemic, Lena Rose Pepperdine died of parrot fever. She was the first wife of George Pepperdine, the founder of Pepperdine University.[14]

References

edit- The initial content for this article was adapted from sources available at https://www.cdc.gov.

- ^ "ornithosis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary[dead link]

- ^ Dugdale, David. "Psittacosis". MediLine Plus. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Horder's spots". GPnotebook.

- ^ Dembek, Zygmunt F.; Mothershead, Jerry L.; Owens, Akeisha N.; Chekol, Tesema; Wu, Aiguo (September 15, 2023). "Psittacosis: An Underappreciated and Often Undiagnosed Disease". Pathogens. 12 (9): 1165. doi:10.3390/pathogens12091165. PMC 10536718. PMID 37764973.

- ^ "Chlamydia Psittaci (Chlamydophila)". Infectious Disease Advisor. January 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare (PDF). National Health and Medical Research Council. May 2019. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-86496-028-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Saif, Y. M. (2003). Diseases of poultry. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Press. p. 863. ISBN 0-8138-0423-X.

- ^ Gregory DW, Schaffner W (1997). "Psittacosis". Semin Respir Infect. 12 (1): 7–11. PMID 9097370.

- ^ a b Potter ME, Kaufmann AK, Plikaytis BD (February 1983). "Psittacosis in the United States, 1979". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 32 (1): 27SS–31SS. PMID 6621602.

- ^ "In 1929, Parrot Fever Gripped The Country". National Public Radio All Things Considered. May 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Winged Wisdom Pet Bird Magazine - Zoonotic (Bird-Human) Diseases: Psittacosis, Salmonellosis". Archived from the original on 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ a b "PSITTACOSIS DISEASE - Pet Birds, Pet Parrots, Exotic Birds". Archived from the original on 2007-11-29. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury College, April 9, 2002, accessed November 14, 2008.

- ^ Baird, W. David (2016). Quest for Distinction: Pepperdine University in the 20th Century. Malibu: Pepperdine University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-9977004-0-4.