Paget's disease of bone (commonly known as Paget's disease or, historically, osteitis deformans) is a condition involving cellular remodeling and deformity of one or more bones. The affected bones show signs of dysregulated bone remodeling at the microscopic level, specifically excessive bone breakdown and subsequent disorganized new bone formation.[1] These structural changes cause the bone to weaken, which may result in deformity, pain, fracture or arthritis of associated joints.[1]

| Paget's disease of bone | |

|---|---|

| Other names | osteitis deformans, Paget's disease |

| |

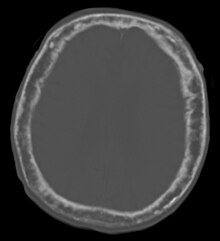

| "This 92 year-old male patient presented for assessment of sudden inability to move half his body. An incidental finding was marked thickening of the calvarium. The diploic space is widened and there are ill-defined sclerotic and lucent areas throughout. The cortex is thickened and irregular. The findings probably correspond to the 'cotton wool spots' seen on plain films in the later stages of Paget's disease." | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Named after | James Paget |

The exact cause is unknown, although leading theories indicate both genetic and acquired factors (see Causes). Paget's disease may affect any one or several bones of the body (most commonly pelvis, tibia, femur, lumbar vertebrae, and skull), but never the entire skeleton,[1][2][3] and does not spread from bone to bone.[4] Rarely, a bone affected by Paget's disease can transform into a malignant bone cancer.

As the disease often affects people differently, treatments of Paget's disease can vary. Although there is no cure for Paget's disease, medications (bisphosphonates and calcitonin) can help control the disorder and lessen pain and other symptoms. Medications are often successful in controlling the disorder, especially when started before complications begin.

Paget's disease affects from 1.5 to 8.0% of the population, and is most common in those of British descent followed by Northern European and Northern Americans.[5] [6] It is primarily diagnosed in older people and is rare in people less than 55 years of age.[7] Men are more commonly affected than women (3:2).[8] The disease is named after English surgeon Sir James Paget, who described it in 1877.

Signs and symptoms

editMild or early cases of Paget's are asymptomatic, and so most people are diagnosed with Paget's disease incidentally during medical evaluation for another problem. Approximately 35% of patients with Paget's have symptoms related to the disease when they are first diagnosed.[7] Overall, the most common symptom is bone pain.[7] When symptoms do occur, they may be confused with those of arthritis or other disorders, and so diagnosis may be delayed. Paget's may first be noticed as an increasing deformity of a person's bones.[9]

Paget's disease affecting the skull may cause frontal bossing, increased hat size, and headaches. Often patients may develop loss of hearing in one or both ears[7] due to auditory foramen narrowing and resultant compression of the nerves in the inner ear. Rarely, skull involvement may lead to compression of the nerves that supply the eye, leading to vision loss.[7]

Associated conditions

editPaget's disease is a frequent component of multisystem proteinopathy. Advanced Paget's disease may lead to other medical conditions, including:

- Osteoarthritis may result from changes in bone shape that alter normal skeletal mechanics. For example, bowing of a femur affected by Paget's may distort overall leg alignment, subjecting the knee to abnormal mechanical forces and accelerating degenerative wear.[10]

- Heart failure is a rare, reported consequence of severe Paget's disease (i.e. more than 40% skeletal involvement). The abnormal bone formation is associated with recruitment of abnormal blood vessels, forcing the cardiovascular system to work harder (pump more blood) to ensure adequate circulation.[11]

- Kidney stones are somewhat more common in patients with Paget's disease.

- Nervous system problems may occur in Paget's disease, resulting from increased pressure on the brain, spinal cord, or nerves, and reduced blood flow to the brain and spinal cord.

- When Paget's disease affects the facial bones, the teeth may become loose. Disturbance in chewing may occur. Chronic dental problems may lead to infection of the jaw bone.

- Angioid streaks may develop, possibly as a result of calcification of collagen or other pathological deposition.[12]

Paget's disease is not associated with osteoporosis. Although Paget's disease and osteoporosis can occur in the same patient, they are different disorders. Despite their marked differences, several treatments for Paget's disease are also used to treat osteoporosis.

Causes

editViral

editPaget's disease may be caused by a slow virus infection (i.e., paramyxoviridae) present for many years before symptoms appear. Associated viral infections include respiratory syncytial virus,[13] canine distemper virus,[14][15] and the measles virus.[16][17] However, recent evidence has cast some doubt upon the measles association.[18] Laboratory contamination may have played a role in past studies linking paramyxovirus (e.g. measles) to Paget's disease.[19]

Genetic

editThere is a hereditary factor in the development of Paget's disease of bone.[20][21] Two genes, SQSTM1 and RANK, and specific regions of chromosome 5 and 6 are associated with Paget's disease of bone. Genetic causes may or may not involve a family history of Paget's disease.[9]

About 40–50% of people with the inherited version of Paget's disease have a mutation in the gene SQSTM1, which encodes a protein, called p62, that is involved in regulating the function of osteoclasts (bone cells).[7] However, about 10–15 percent of people that develop the disease without any family history also have a mutation in the SQSTM1 gene.[7]

Paget's disease of bone is associated with mutations in RANK. Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κ B (RANK), which is a type I membrane protein that is expressed on the surface of osteoclasts and is involved in their activation upon ligand binding.[22] Additional genetic associations include:

| Name | OMIM | Locus | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB1 | 167250 | 6p | ? |

| PDB2 | 18q22.1 | RANK | |

| PDB3 | 5q35 | SQSTM1 | |

| PDB4 | 606263 | 5q31[23] | ? |

Pathogenesis

editThe pathogenesis of Paget's disease is described in four stages:[24]

- Osteoclastic activity

- Mixed osteoclastic – osteoblastic activity

- Osteoblastic activity

- Malignant degeneration

Initially, there is a marked increase in the rate of bone resorption in localized areas, caused by large and numerous osteoclasts. Radiographs at this phase show lucency in the affected bone. These localized areas of pathological destruction of bone tissue (osteolysis) are seen radiologically as an advancing lytic wedge in long bones or the skull. When this occurs in the skull, it is called osteoporosis circumscripta. The osteolysis is followed by a compensatory increase in bone formation and increase in alkaline phosphatase levels induced by the bone-forming cells, called osteoblasts, that are recruited to the area. This is associated with accelerated deposition of lamellar bone in a disorganized fashion. Woven bone, rather than lamellar bone, predominates and mineralization occurs at twice the normal rate.[5] This intense cellular activity produces a chaotic picture of trabecular bone ("mosaic" pattern), rather than the normal linear lamellar pattern. The resorbed bone is replaced and the marrow spaces are filled by an excess of fibrous connective tissue with a marked increase in blood vessels, causing the bone to become hypervascular. The bone hypercellularity may then diminish, leaving a dense "pagetic bone", also known as burned-out Paget's disease. A later phase of the disease is characterized by the replacement of normal bone marrow with highly vascular fibrous tissue.[25]

Sir James Paget first suggested the disease was due to an inflammatory process. Some evidence suggests that a paramyxovirus infection is the underlying cause of Paget's disease,[7] which may support the possible role of inflammation in the pathogenesis. However, no infectious virus has yet been isolated as a causative agent, and other evidence suggests an intrinsic hyperresponsive reaction to vitamin D and RANK ligand is the cause.[citation needed] Further research is therefore necessary.[26]

Diagnosis

editThe first clinical manifestation of Paget's disease is usually an elevated alkaline phosphatase in the blood.[7]

Paget's disease may be diagnosed using one or more of the following tests:

- Pagetic bone has a characteristic appearance on X-rays. A skeletal survey is therefore indicated.

- An elevated level of alkaline phosphatase in the blood in combination with normal calcium, phosphate, and aminotransferase levels in an elderly patient are suggestive of Paget's disease.

- Markers of bone turnover in urine eg. Pyridinoline

- Elevated levels of serum and urinary hydroxyproline are also found.

- Bone scans are useful in determining the extent and activity of the condition. If a bone scan suggests Paget's disease, the affected bone(s) should be X-rayed to confirm the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

edit| Condition | Calcium | Phosphate | Alkaline phosphatase | Parathyroid hormone | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteopenia | unaffected | unaffected | normal | unaffected | decreased bone mass |

| Osteopetrosis | unaffected | unaffected | elevated | unaffected [citation needed] | thick dense bones also known as marble bone |

| Osteomalacia and rickets | decreased | decreased | elevated | elevated | soft bones |

| Osteitis fibrosa cystica | elevated | decreased | elevated | elevated | brown tumors |

| Paget's disease of bone | unaffected | unaffected | variable (depending on stage of disease) | unaffected | abnormal bone architecture |

Treatment

editAlthough initially diagnosed by a primary care physician, endocrinologists (internal medicine physicians who specialize in hormonal and metabolic disorders), rheumatologists (internal medicine physicians who specialize in joint and muscle disorders), orthopedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, neurologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, and otolaryngologists are generally knowledgeable about treating Paget's disease and may be called upon to evaluate specialized symptoms. It can sometimes be difficult to predict whether a person with Paget's disease, who otherwise has no signs or symptoms of the disorder, will develop symptoms or complications (such as a bone fracture) in the future.[citation needed]

Medication

editThe goal of treatment is to relieve bone pain and prevent the progression of the disease.[9] These medications are usually recommended for people with Paget's disease who:[citation needed]

- have bone pain, headache, back pain, or a nerve-related symptom (such as "shooting" pains in the leg) that is directly associated with the disease;

- have elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in their blood;

- display evidence that a bone fracture will occur;

- require pretreatment therapy for affected bones that require surgery;

- have active symptoms in the skull, long bones, or vertebrae (spine);

- have the disease in bones located next to major joints, placing them at risk of developing osteoarthritis;

- develop hypercalcemia that occurs when a person, with several bones affected by Paget's disease and a high serum alkaline phosphatase level, is immobilized.

Bisphosphonates

editFive bisphosphonates are currently available. In general, the most commonly prescribed are risedronic acid, alendronic acid, and pamidronic acid. Etidronic acid and other bisphosphonates may be appropriate therapies for selected patients but are less commonly used. In one study it was reported that people experienced side effects when taking bisphosphonates for six months, however the quality of evidence was low.[27] None of these drugs should be used by people with severe kidney disease.[citation needed]

- Neridronate

- Etidronate disodium The approved regimen is once daily for six months; a higher dose is more commonly used. No food, beverage, or medications should be consumed for two hours before and after taking. The course should not exceed six months, but repeat courses can be given after rest periods, preferably of three to six months duration.

- Pamidronate disodium in intravenous form: the approved regimen uses an infusion over four hours on each of three consecutive days, but a more commonly used regimen is over two to four hours for two or more consecutive or nonconsecutive days.

- Alendronate sodium is given as tablets once daily for six months; patients should wait at least 30 minutes after taking before eating any food, drinking anything other than tap water, taking any medication, or lying down (patient may sit).

- Tiludronate disodium is taken once daily for three months; they may be taken any time of day, as long as there is a period of two hours before and after resuming food, beverages, and medications.

- Risedronate sodium tablet taken once daily for 2 months is the prescribed regimen; patients should wait at least 30 minutes after taking before eating any food, drinking anything other than tap water, taking any medication, or lying down (patient may sit).

- Zoledronic acid is given as an intravenous infusion; a single dose is effective for two years. This is recommended for most people at high risk with active disease.[28]

Calcitonin

editSalcatonin, also called calcitonin-salmon is a synthetic copy of a polypeptide hormone secreted by the ultimobranchial gland of salmon. Miacalcin is administered by injection, three times per week or daily, for 6–18 months. Repeat courses can be given after brief rest periods. Miacalcin may be appropriate for certain patients but is seldom used. Calcitonin was putatively linked to increased chance of cancer.[29] The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended that calcitonin be used only on a short-term basis for 3 conditions for which it had previously been approved in the European Union: Paget's disease, acute bone loss resulting from sudden immobilization, and hypercalcemia caused by cancer. As a solution for injection or infusion, calcitonin should be administered for no more than 4 weeks to prevent acute bone loss resulting from sudden immobilization, and normally for no more than 3 months to treat Paget's disease, the EMA said. The agency did not specify a time frame for the short-term use of calcitonin for treating hypercalcemia caused by cancer. The EMA based its recommendations on a review of the benefits and risks of calcitonin-containing medicines. Conducted by the agency's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), the review encompassed available data from the companies that market these drugs, postmarketing safety data, randomized controlled studies, 2 studies of unlicensed oral calcitonin drugs, and experimental cancer studies, among other sources.[30]

In 2014, the FDA noted the risk imbalances in the prescribing information for Miacalcin but declined to label this product with a boxed warning as a causal association was not identified.[31]

A more recent meta-analysis determined that a causal link between calcitonin and cancer is both unlikely and antithetical to known biology, although a weak association was not definitively excluded.[32] The available studies for analysis were inconsistent and nonspecific, with one study[33] noting an increased risk of liver cancer and decreased risk of breast cancer. This was not replicated in any other study.[citation needed]

Additionally, there is question of the overall efficacy of calcitonin-containing nasal sprays. A phase III trial found no difference between placebo and nasal calcitonin sprays on lumbar bone mineral density in osteoporosis.[34] It did find a significant increase in bone mineral density with oral calcitonin. This result was replicated in another study,[35] but this study found that the bone mineral density increase did not significantly impact fracture risk. However, these studies were only inclusive of osteoporosis.

Surgery

editMedical therapy prior to surgery helps to decrease bleeding and other complications. Patients who are having surgery should discuss treatment with their physician. There are generally three major complications of Paget's disease for which surgery may be recommended.[9]

- Fractures – Surgery may allow fractures to heal in a better position.

- Severe degenerative arthritis – If disability is severe and medication and physical therapy are no longer helpful, joint replacement of the hips and knees may be considered.

- Bone deformity – Cutting and realignment of pagetic bone (osteotomy) may help painful weight bearing joints, especially the knees.

Complications resulting from enlargement of the skull or spine may injure the nervous system. However, most neurologic symptoms, even those that are moderately severe, can be treated with medication and do not require neurosurgery.[citation needed]

Diet and exercise

editIn general, patients with Paget's disease should receive 1000–1500 mg of calcium, adequate sunshine, and at least 400 units of vitamin D daily. This is especially important in patients being treated with bisphosphonates; however, taking oral bisphosphonates should be separated from taking calcium by at least two hours, because the calcium can inhibit the absorption of the bisphosphonate. Patients with a history of kidney stones should discuss calcium and vitamin D intake with their physicians. [36]

Exercise is very important in maintaining skeletal health, avoiding weight gain, and maintaining joint mobility. Since undue stress on affected bones should be avoided, people with Paget's disease of bone should discuss any exercise program with their physicians or physical therapists before beginning.[citation needed]

Prognosis

editThe disease is progressive and slowly worsens with time, although people may remain minimally symptomatic. Treatment is aimed at controlling symptoms, but there is no cure. Any bone or bones can be affected, but Paget's disease occurs most frequently in the spine, skull, pelvis, femur, and lower legs. Osteogenic sarcoma, a form of bone cancer, is a rare complication of Paget's disease occurring in less than one percent of those affected. The development of osteosarcoma may be suggested by the sudden onset or worsening pain.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

editPaget's disease of bone is the second most common metabolic bone disorder, after osteoporosis.[37] The overall prevalence and severity of Paget's disease are decreasing; the cause for these changes is unclear.[38] Paget's disease is rare in people less than 55 years of age,[7] and the prevalence increases with age.[38] Evidence from studies of autopsy results have demonstrated Paget's disease in about 3 percent of people older than 40 years of age.[38] Paget's disease is more common in males than females.[8] Rates of Paget's disease are about 50 percent higher in men than in women.

About 15 percent of people with Paget's disease also have a family member with the disease.[7] In cases where the disease is familial, it is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, although not all people that inherit the affected version of the genes will express the disease (incomplete penetrance).[7]

The incidence of Paget's disease varies considerably with geographic location.[38] Paget's predominantly affects people of European descent, whereas people of African, Asian, or Indian descent are less commonly affected.[7] Paget's disease is less common in Switzerland and Scandinavia than in the rest of Western Europe.[38] Paget's disease is uncommon in the native populations of North and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. When an individual from these regions does develop Paget's disease, there is typically some European ancestry present.[citation needed]

History

editThe condition was initially described by Dr. James Paget. In a paper published in 1877, Paget told of five patients with "a rare disease of bones" which presented with slowly progressive bone deformities in the 4th and 5th decades of age.[39] Strikingly, the first patient was described to have many of the classic complications of the disease, including arthritis related to abnormal bone mechanics, cranial nerve palsies associated with an enlarging skull, and malignant transformation of a tumor of the radius which ultimately proved fatal. Paget's post-mortem autopsy evaluation showed "bones of the vault of this skull were in every part increased to about four times the normal thickness," and microscopic evaluation showed evidence of both bone erosion and abnormal remodeling. Although he incorrectly attributed the findings to a process of chronic inflammation, having ruled out tumor and hypertrophy as alternative etiologies, these prescient observations of a mixed destructive/regenerative process correspond to the modern understanding of the disease.

Holding, then, the disease to be an inflammation of bones, I would suggest that, for brief reference, and for the present, it may be called, after its most striking character, Osteitis deformans. A better name may be given when more is known of it.

— James Paget, Paget J. On a form of chronic inflammation of bone (osteitis deformans). Medico-cirurgical Transactions of London 1887;60:37-63.

Paget's disease of bone was originally termed osteitis deformans, because it was thought to involve an inflammatory process, which is implied by the suffix -itis. Now, that term is considered technically incorrect, and the preferred term is osteodystrophia deformans.[40]

Society and culture

edit- Viking warrior and poet Egill Skallagrímsson may have had Paget's disease.[41][42]

- Ludwig van Beethoven is speculated to have had Paget's disease based on autopsy description, and which may have contributed to his well-known deafness.[43]

- Retired Boston Red Sox center fielder Dom DiMaggio had Paget's disease and served as a member of the board of directors of the Paget Foundation.[44]

- American retired boxer Red Burman died of Paget's disease in 1996.[45]

References

edit- ^ a b c Paul Tuck, Stephen; Layfield, Robert; Walker, Julie; Mekkayil, Babitha; Francis, Roger (December 2017). "Adult Paget's disease of bone: a review". Rheumatology. 56 (12): 2050–2059. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew430. PMID 28339664.

- ^ Daroszewska, A.; Ralston, S. H. (2006). "Mechanisms of Disease: genetics of Paget's disease of bone and related disorders". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2 (5): 270–277. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0172. PMID 16932700. S2CID 22051952.

- ^ Ralston, Stuart H.; Layfield, Rob (29 April 2012). "Pathogenesis of Paget Disease of Bone". Calcified Tissue International. 91 (2): 97–113. doi:10.1007/s00223-012-9599-0. PMID 22543925. S2CID 17244878.

- ^ Charles, Julia F.; Siris, Ethel S.; Roodman, G. David (2018). "Paget Disease of Bone". Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 713–720. ISBN 978-1-119-26656-3.

- ^ a b Greene, Walter B. (1 December 2005). Netter's Orthopaedics (1st ed.). Saunders. p. 38. ISBN 978-1929007028.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Nebot Valenzuela, Elena; Pietschmann, Peter (6 September 2016). "Epidemiology and pathology of Paget's disease of bone – a review". Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 167 (1–2): 2–8. doi:10.1007/s10354-016-0496-4. PMC 5266784. PMID 27600564.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ralston, Stuart H. (14 February 2013). "Paget's Disease of Bone". New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (7): 644–650. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1204713. PMID 23406029.

- ^ a b Kumar, Parveen; Clark, Micheal (2009). Welcome to Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (7th ed.). Elsiver. p. 565. ISBN 978-0-7020-2993-6.

- ^ a b c d "Paget's Disease of Bone". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Osteoarthritis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Chakravorty, N.K. (1978). "Some Unusual Features of Paget's Disease of Bone". Gerontology. 24 (6): 459–472. doi:10.1159/000212286. PMID 689380.

- ^ DermAtlas Archived June 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine - Johns Hopkins

- ^ Mills, B. G.; Singer, F. R.; Weiner, L. P.; Holst, P. A. (1 February 1981). "Immunohistological demonstration of respiratory syncytial virus antigens in Paget disease of bone". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 78 (2): 1209–1213. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.1209M. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.2.1209. PMC 319977. PMID 6940136.

- ^ Hoyland, Judith A; Dixon, Janet A; Berry, Jacqueline L; Davies, Michael; Selby, Peter L; Mee, Andrew P (May 2003). "A comparison of in situ hybridisation, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and in situ-RT-PCR for the detection of canine distemper virus RNA in Paget's disease". Journal of Virological Methods. 109 (2): 253–259. doi:10.1016/s0166-0934(03)00079-x. PMID 12711070.

- ^ Gordon, M.T.; Anderson, D.C.; Sharpe, P.T. (January 1991). "Canine distemper virus localised in bone cells of patients with Paget's disease". Bone. 12 (3): 195–201. doi:10.1016/8756-3282(91)90042-h. PMID 1910961.

- ^ Friedrichs, William E.; Reddy, Sakamuri V.; Bruder, Jan M.; Cundy, Tim; Cornish, Jillian; Singer, Frederick R.; Roodman, G. David (1 January 2002). "Sequence Analysis of Measles Virus Nucleocapsid Transcripts in Patients with Paget's Disease". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 17 (1): 145–151. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.145. PMID 11771661. S2CID 23137395.

- ^ Basle, M. F.; Fournier, J. G.; Rozenblatt, S.; Rebel, A.; Bouteille, M. (1 May 1986). "Measles Virus RNA Detected in Paget's Disease Bone Tissue by in situ Hybridization". Journal of General Virology. 67 (5): 907–913. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-5-907. PMID 3701300.

- ^ Matthews, Brya G.; Afzal, Muhammad A.; Minor, Philip D.; Bava, Usha; Callon, Karen E.; Pitto, Rocco P.; Cundy, Tim; Cornish, Jill; Reid, Ian R.; Naot, Dorit (April 2008). "Failure to Detect Measles Virus Ribonucleic Acid in Bone Cells from Patients with Paget's Disease". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 93 (4): 1398–1401. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1978. PMID 18230662.

- ^ Ralston, Stuart H; Afzal, Muhammad A; Helfrich, Miep H; Fraser, William D; Gallagher, James A; Mee, Andrew; Rima, Bert (8 January 2007). "Multicenter Blinded Analysis of RT-PCR Detection Methods for Paramyxoviruses in Relation to Paget's Disease of Bone". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 22 (4): 569–577. doi:10.1359/jbmr.070103. PMID 17227218.

- ^ Ralston, Stuart H; Langston, Anne L; Reid, Ian R (July 2008). "Pathogenesis and management of Paget's disease of bone". The Lancet. 372 (9633): 155–163. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61035-1. PMID 18620951. S2CID 860027.

- ^ Whyte, M. P. (1 April 2006). "Paget's Disease of Bone and Genetic Disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK/NF- B Signaling". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1068 (1): 143–164. Bibcode:2006NYASA1068..143W. doi:10.1196/annals.1346.016. PMID 16831914. S2CID 35993578.

- ^ Haslam, Sonya I.; Van Hul, Wim; Morales-Piga, Antonio; Balemans, Wendy; San-Millan, J. L.; Nakatsuka, Kiyoshi; Willems, Patrick; Haites, Neva E.; Ralston, Stuart H. (1 June 1998). "Paget's Disease of Bone: Evidence for a Susceptibility Locus on Chromosome 18q and for Genetic Heterogeneity". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 13 (6): 911–917. doi:10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.6.911. PMID 9626621. S2CID 20552512.

- ^ Laurin, Nancy; Brown, Jacques P.; Lemainque, Arnaud; Duchesne, Annie; Huot, Denys; Lacourcière, Yves; Drapeau, Gervais; Verreault, Jean; Raymond, Vincent; Morissette, Jean (September 2001). "Paget Disease of Bone: Mapping of Two Loci at 5q35-qter and 5q31". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (3): 528–543. doi:10.1086/322975. PMC 1235483. PMID 11473345.

- ^ Michou, Laëtitia; Numan, Mohamed; Amiable, Nathalie; Brown, Jacques P (August 2015). "Paget's disease of bone: an osteoimmunological disorder?". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 9: 4695–707. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S88845. PMC 4544727. PMID 26316708.

- ^ Tamparo, Carol; Lewis, Marcia (2011). Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- ^ Basic Pathology, Kumar Abbas Fausto Mitchell, Saunders Elsevier[page needed]

- ^ Corral-Gudino, Luis; Tan, Adrian JH; del Pino-Montes, Javier; Ralston, Stuart H (1 December 2017). "Bisphosphonates for Paget's disease of bone in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (12): CD004956. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004956.pub3. PMC 6486234. PMID 29192423.

- ^ Singer, Frederick R.; Bone, Henry G.; Hosking, David J.; Lyles, Kenneth W.; Murad, Mohammad Hassan; Reid, Ian R.; Siris, Ethel S.; Endocrine, Society. (December 2014). "Paget's Disease of Bone: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 99 (12): 4408–4422. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2910. PMID 25406796.

- ^ Lowes, Robert (20 July 2012). "Calcitonin Linked to Cancer Risk, EMA Warns". Medscape. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

A higher proportion of patients treated with calcitonin for long periods of time develop cancer of various types, compared with patients taking placebo. The increase in cancer rates ranged from 0.7% for oral formulations to 2.4% for the nasal formulation.

- ^ "Calcitonin". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (3 November 2018). "Questions and Answers: Changes to the Indicated Population for Miacalcin (calcitonin-salmon)". FDA.

- ^ Wells, G.; Chernoff, J.; Gilligan, J. P.; Krause, D. S. (2016). "Does salmon calcitonin cause cancer? A review and meta-analysis". Osteoporosis International. 27 (1): 13–19. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3339-z. PMC 4715844. PMID 26438308.

- ^ Sun, Li-Min; Lin, Ming-Chia; Muo, Chih-Hsin; Liang, Ji-An; Kao, Chia-Hung (November 2014). "Calcitonin Nasal Spray and Increased Cancer Risk: A Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 99 (11): 4259–4264. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2239. PMID 25144633.

- ^ Binkley, Neil; Bolognese, Michael; Sidorowicz-Bialynicka, Anna; Vally, Tasneem; Trout, Richard; Miller, Colin; Buben, Christine E; Gilligan, James P; Krause, David S; Oral Calcitonin in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis (ORACAL), Investigators. (August 2012). "A phase 3 trial of the efficacy and safety of oral recombinant calcitonin: The oral calcitonin in postmenopausal osteoporosis (ORACAL) trial". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 27 (8): 1821–1829. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1602. PMID 22437792.

- ^ Henriksen, Kim; Byrjalsen, Inger; Andersen, Jeppe R.; Bihlet, Asger R.; Russo, Luis A.; Alexandersen, Peter; Valter, Ivo; Qvist, Per; Lau, Edith; Riis, Bente J.; Christiansen, Claus; Karsdal, Morten A.; SMC021, investigators. (October 2016). "A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral salmon calcitonin in the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women taking calcium and vitamin D". Bone. 91: 122–129. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2016.07.019. PMID 27462009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Branch, NIAMS Science Communications and Outreach (2017-04-06). "Paget's Disease of Bone: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Steps to Take". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Alonso, N.; Calero-Paniagua, I.; del Pino-Montes, J. (19 December 2016). "Clinical and Genetic Advances in Paget's Disease of Bone: a Review". Clinical Reviews in Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 15 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1007/s12018-016-9226-0. PMC 5309316. PMID 28255281.

- ^ a b c d e Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (2011-07-21). Harrison's principles of internal medicine:Chapter 355. Paget's Disease and Other Dysplasias of Bone (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ^ Paget, James (1887). "On a form of chronic inflammation of bone (osteitis deformans)". Medico-cirurgical Transactions of London. 60: 37–63.

- ^ Rhodes, B.; Jawad, A. S. M. (6 January 2005). "Paget's disease of bone: osteitis deformans or osteodystrophia deformans?". Rheumatology. 44 (2): 261–262. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh448. PMID 15637095.

- ^ Byock, Jesse L. (January 1995). "Egil's Bones". Scientific American. pp. 82–87. Retrieved 2015-07-06 – via The Viking Site.

- ^ "Snæfellsnes". Sögustaðir með Evu Maríu (in Icelandic). 9 June 2019. Event occurs at 12:18. RÚV. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ Oiseth, Stanley J (27 October 2015). "Beethoven's autopsy revisited: A pathologist sounds a final note". Journal of Medical Biography. 25 (3): 139–147. doi:10.1177/0967772015575883. PMID 26508624. S2CID 19048190.

- ^ "Paid Notice: Deaths DIMAGGIO, DOMINIC P". The New York Times. May 10, 2009.

- ^ "'Red' Burman gave Joe Louis a battle in 1941 fight for title Baltimore native dies at 80 after long illness". 25 January 1996.

External links

edit- Paget's Disease of Bone Overview - NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases ~ National Resource Center