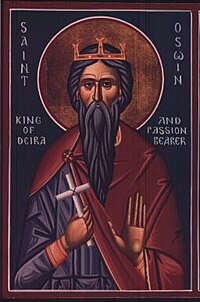

Oswine, Oswin or Osuine (died 20 August 651) was a King of Deira in northern England.

Oswine of Deira | |

|---|---|

| |

| King, Martyr | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | 20 August, 651 Gilling, Yorkshire, England |

| Venerated in | Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Anglican Communion |

| Major shrine | Tynemouth, England |

| Feast | 20 August |

Life

editOswine succeeded King Oswald of Northumbria, probably around the year 644, after Oswald's death at the Battle of Maserfield.[1] Oswine was the son of Osric. His succession, perhaps the choice of the people of Deira,[2] split the Kingdom of Northumbria. Oswiu was the successor of Bernicia to the north.[3]

After seven years of peaceful rule, Oswiu declared war on Oswine. Oswine refused to engage in battle, instead retreating to Gilling and the home of his friend, Earl Humwald.[4] Humwald betrayed Oswine, delivering him to Oswiu's soldiers by whom Oswine was put to death,[5] probably at Diddersley Hill in North Yorkshire.

Bede recounted the death of King Oswine in 651 and mentioned a place called "Wilfaresdun," which he explained to mean "Wilfar's Hill". According to Bede, this location was located approximately ten miles away from the village called Cataract, towards the northwest. King Oswin sought refuge in the house of Earl Hunwald, whom he believed to be his loyal friend, along with only one trusted soldier named Tonhere. However, Earl Hunwald betrayed him, and King Oswin was ultimately killed by Ethilwin, Oswy's commander, in a treacherous manner"[6] Bede provides us with the following account of the events: [7]

Remisit exercitum quem congregaverat, ac singulos domum redire praecepit, a loco qui vocatur Vilfaraesdun, id est Mons Vilfari, et set a vico Cataractone decem ferme millibus passum contra solistitialem occasum secretus: divertitque ipse cum uno tantum milite sibi fidelissimo, nomine Tondheri, celandus in domo comitis Hunualdi, quem etiam ipsum sibi amicissimum autumabat. Sed, heu, proh dolor! longe aliter erat: nam ab eodem comite proditum eum Osuiu, eum praefato ipsius milite per praefectum suum Ediluinum detestanda omnibus morte interfecit. Quod factum est die decima tertia Kalendarum Septembrium, anno regni eius nono, in loco qui dicitur Ingetlingum.

Understanding this to describe a prominent hill located ten Roman miles (i.e. about 9 imperial miles along the old Roman road) northwest of Catterick, then we are left with one possible location for Wilfar's Hill: Diddersley Hill.

Veneration

editIn Anglo-Saxon culture, it was assumed that the nearest kinsmen to a murdered person would seek to avenge the death or require some other kind of justice on account of it (such as the payment of wergild: a sum of money paid to the relatives of a slain man on account of the killing). However, Oswine's nearest kinsman was Oswiu's own wife. Oswiu was also related to the slain. In order to confront the justice that was seen to be owed for the murder, Oswiu founded Gilling Abbey, a monastery partly staffed by the relatives of both of their families, and this monastery was given the task of offering prayers for both Oswiu's salvation and Oswine's departed soul. It was from the same monastery, many years later, that Oswine was later claimed to be a saint.[8]

Oswine is one of many Anglo-Saxon royals who were honoured in monasteries and developed cults as saints. Another example is Edward the Martyr.

Oswine was buried at Tynemouth, but the place of burial was later forgotten. It is said that his burial place was made known by an apparition to a monk named Edmund,[2] and his relics were translated to an honorable place in Tynemouth Priory in 1065.[9] According to Alban Butler, in 1103, Ranulf Flambard, Bishop of Durham, translated the remains from the chapel at Tynemouth, which had fallen into disrepair, to St Alban's Abbey in Hertfordshire.[10]

There was a cult of Saint Oswin as a Christian martyr because he had died "if not for the faith of Christ, at least for the justice of Christ".

St Oswin's Church, Wylam

editThe Church of England parish church of Wylam, Northumberland, England is dedicated to Saint Oswin. The church was built in 1886 and currently has a congregation of about 150. The church has a peal of 6 bells (in the tower) and has regular Sunday services with ringing.

Our Lady & St Oswin's Church, Tynemouth

editSt Oswin is co-patron (with Our Lady) of the Catholic parish of Tynemouth with a church at the end of Front Street not far from the ruins of the priory where Oswin was buried.

References

edit- ^ Turner, Joseph (1897). Ancient Bingley: Or, Bingley, Its History and Scenery. University of California Libraries. p. 34. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

oswin of deira 644.

- ^ a b Parker, Anselm. "St. Oswin." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 28 Mar. 2013

- ^ "St. Oswin, King of Deira (AD -AD 651)". Britannia.com. Britannia.com, LLC. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Strutt, Joseph (1777). From the Arrival of Julius Caesar to the End of the Saxon Heptarchy. Joseph Cooper. p. 139. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Hutchinson, William (1817). The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham (Volume 1 ed.). p. 9. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Bede (1990). Ecclesiastical history of the English people : with Bede's letter to Egbert. David Hugh Farmer, R. E. Latham, Saint Egbert (Revised ed.). London, England. pp. Book III, Chapter 14. ISBN 0-14-044565-X. OCLC 24111793.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Baedae Opera historica: with an English translation. Translated by King, J. E. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1930. p. 394. ISBN 0-674-99271-7. OCLC 685457.

- ^ Studies in the Early history of Shaftesbury Abbey, Dorset County Council, 1999

- ^ Monks of Ramsgate. “Oswin”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 19 May 2016

- ^ Butler, Alban. “Saint Oswin, King and Martyr”. Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. CatholicSaints.Info. 26 July 2014

Sources

edit- Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, ed. and tr. B. Colgrave and R.A.B. Mynors, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford, 1969.

- Anonymous, Vita Oswini (twelfth century), ed. James Raine, Miscellanea Biographica. Publications of the Surtees Society 8. London, 1858. 1-59. PDF available from Internet Archive.

Further reading

edit- Chase, Colin. "Beowulf, Bede, and St. Oswine: The Hero's Pride in Old English Hagiography." The Anglo-Saxons. Synthesis and Achievement, ed. J. Douglas Woods and David A.E. Pelteret. Waterloo (Ontario), 1985. 37–48. Reprinted in The Beowulf Reader, ed. Peter S. Baker. New York and London, 2000. 181–93.