Owain ap Gruffydd (c. 1354 – 20 September 1415), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr (Glyn Dŵr, pronounced [ˈoʊain ɡlɨ̞nˈduːr], anglicised as Owen Glendower) was a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander in the late Middle Ages, who led a 15-year-long Welsh revolt with the aim of ending English rule in Wales. He was an educated lawyer, forming the first Welsh parliament under his rule, and was the last native-born Welshman to claim the title Prince of Wales.

| Owain Glyndŵr | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Owain Glyndŵr from his great seal | |

| Baron of Glyndyfrdwy, and Lord of Cynllaith Owain | |

| Reign | c. 1370-1400 |

| Predecessor | Lord Gruffydd Fychan II |

| Successor | Abolished |

| Prince of Wales | |

| Reign | 1400–1415[a] |

| Predecessor | Welsh: Dafydd ap Gruffydd (1282-1283) English: Henry of Monmouth (1399–1400) |

| Successor | Welsh: Vacant English: Edward of Westminster (1453–1471) |

| Born | Owain ap Gruffydd c. 1354 Sycharth, Wales |

| Died | 20 September 1415 (aged 60–61) |

| Burial | 21 September 1415 (unknown location)[b] |

| Spouse | Margaret Hanmer |

| Issue among others | |

| House | Mathrafal |

| Father | Gruffudd Fychan II |

| Mother | Elen ferch Tomas ap Llywelyn |

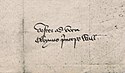

| Signature |  |

During the year 1400, Owain Glyndŵr, a Welsh soldier and Lord of Glyndyfrdwy had a dispute with a neighbouring English Lord, the event spiralled into a national revolt which pitted common Welsh countrymen and nobles against the English military. In response to the rebellion, discriminatory penal laws were implemented against the Welsh people; this deepened civil unrest and significantly increased support for Glyndŵr across Wales. Then, in 1404, after a series of successful castle sieges and several battlefield victories for the Welsh, Owain gained control of most of Wales and was proclaimed by his supporters as the Prince of Wales, in the presence of envoys from several other European kingdoms, and military aid was given from France, Brittany, and Scotland. He proceeded to summon the first Welsh parliament in Machynlleth, where he outlined his plans for Wales which included building two universities, reinstating the medieval Welsh laws of Hywel Dda, and build an independent Welsh church.

The war continued, and over the next several years, the English gradually gained control of large parts of Wales. By 1409 Owain’s last remaining castles of Harlech and Aberystwyth had been captured by English forces. Glyndŵr refused two royal pardons and retreated to the Welsh hills and mountains with his remaining forces, where he continued to resist English rule by using guerrilla warfare tactics, until his disappearance in 1415, when he was recorded to have died by one of his followers Adam of Usk.

Glyndŵr was never captured or killed, and he was also never betrayed despite being a fugitive of the law with a large bounty. In Welsh culture he acquired a mythical status alongside Cadwaladr, Cynon ap Clydno and King Arthur as a folk hero - 'The Foretold Son' (Welsh:Y Mab Darogan). Centuries after Glyndwr's death, in William Shakespeare's play Henry IV, Part 1 he appears as the character Owen Glendower as a king rather than a prince.

Early life and marriage

editOwain ap Gruffydd (Owain Glyndŵr) was born during 1354 (1359?) in Sycharth, North East Wales, into a powerful Anglo-Welsh gentry family. His father, Gruffydd Fychan II had a claim to be hereditary Prince of Powys Fadog and was the Baron of Glyndyfrdwy and Lord of Cynllaith Owain, who died around 1370,[1] leaving Glyndŵr's mother Elen ferch Tomas ap Llywelyn, a woman with an accent from Ceredigion (Deheubarth), a widow when he was still a boy.[2] Owain Glyndŵr was a descendant of all three Welsh Royal Principalities (royal houses). Through his father, he was the heir of the former Kingdom of Powys (House of Mathrafal). And through his mother, he was the direct descendant and heir of both Deheubarth (House of Dinefwr) and Gwynedd (House of Aberffraw).[3][4] He may also have been a descendant of the English King Edward I, through his granddaughter Eleanor.[5][6] However the existence of Eleanor is disputed.[7]

The young Owain ap Gruffydd was possibly fostered at the home of David Hanmer, a rising lawyer shortly to be a justice of the King's Bench, or at the home of Richard FitzAlan, 3rd Earl of Arundel. Owain is then thought to have been sent to London to study law at the Inns of Court, as a student in Westminster, London,[8][9] for over a period of seven years. He was possibly in London during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.[10] By 1384, he was living in Wales and married to David's daughter, Margaret Hanmer;[11] their marriage took place, perhaps in 1383, in St Chad's Church, Hanmer in north-east Wales.[12] Although other sources state that they were married in the 1370s.[13] They started a large family and Owain established himself as the squire of his ancestral lands at Sycharth and Glyndyfrdwy.[14]

Military service

editGlyndŵr joined the king's military service in 1384 when he undertook garrison duty under the renowned Welshman Sir Gregory Sais on the English–Scottish border at Berwick-upon-Tweed. His surname Sais, meaning 'Englishman' in Welsh, refers to his ability to speak English, not common in Wales at the time.[15] In August 1385, he served King Richard II under the command of John of Gaunt, again in Scotland.[16][17][18] Then, in 1386, he was called to give evidence at the High Court of Chivalry,[9] in the Scrope v Grosvenor trial at Chester on 3 September that year. In March 1387, Owain fought as a squire to Richard FitzAlan, 4th Earl of Arundel,[16] where he saw action in the English Channel at the defeat of a Franco-Spanish-Flemish fleet off the coast of Kent. Upon the death in late 1387 of his father-in-law, Sir David Hanmer, knighted earlier that same year by the then King of England, Richard II, Glyndŵr returned to Wales as executor of his estate.[19] Glyndŵr next served as a squire to Henry Bolingbroke (later King Henry IV),[20] son of John of Gaunt, at the short Battle of Radcot Bridge in December 1387.[9] From 1384 until 1388 he had been active in military service and had gained three full years of military experience in different theatres, and had witnessed some key events and noteworthy people at first hand.[21]

King Richard was distracted by a growing conflict with the Lords Appellant from this time on. Glyndŵr's opportunities were further limited by the death of Sir Gregory Sais in 1390 and the sidelining of FitzAlan, and he probably returned to his stable Welsh estates,[citation needed] living there quietly for ten years during his forties. The bard Iolo Goch, himself a Welsh Lord, visited Glyndŵr in Sycharth in the 1390s and wrote a number of odes to Owain, praising his host's liberality and writing of Sycharth, "Very rarely was a bolt or lock to be seen there."[22][23]

Glyndŵr's Welsh rebellion

editPrequel to rebellion

editIn the late 1390s, a series of events occurred which cornered Owain, and forced his ambitions towards a rebellion. The events would later be called the Welsh Revolt, the Glyndŵr Rising (within Wales), or the Last War of Independence. His neighbour, Baron Grey of Ruthin, had seized control of some land, for which Glyndŵr appealed to the English Parliament, however, Owain's petition for redress was ignored. Later, in 1400, Lord Grey did not inform Glyndŵr in time about a royal command to levy feudal troops for Scottish border service, thus enabling him to call Glyndŵr a traitor in London court circles.[24] Lord Grey had stature in the royal court of Henry IV. The law courts refused to hear the case, or it was delayed because Lord Grey prevented Owain's letter from reaching the King, which would have repercussions.[25] Sources state that Glyndŵr was under threat because he had written an angry letter to Lord Grey, boasting that lands had come into his possession, and he had stolen some of Lord Grey's horses; and believing Lord Grey had threatened to "burn and slay" within his lands, he threatened retaliation in the same manner. Lord Grey then denied making the initial threat to burn and slay, and replied that he would take the incriminating letter to Henry IV's council and that Glyndŵr would hang for the admission of theft and treason contained within the letter.[26] The deposed king, Richard II, had support in Wales, and in January 1400 serious civil disorder broke out in the English border city of Chester after the public execution of an officer of Richard II.[27][28]

Initial revolts

editAt Sycharth, in Glyndyfrdwy on 16 September 1400, in front of his immediate family, his in-laws, Welsh people from Berwyn, friends from North-East Wales, the Dean of St Asaph totalling 300 men, Owain Glyndŵr prophecised that he was the person to save his people from the English invasions, and proclaimed himself the Prince of Wales. And, after that day, he instigated a 15-year rebellion against the rule of Henry IV. Then came a number of initial confrontations between Henry IV and Owain's followers in September and October 1400, as the revolt began to spread around North Wales.[29] Glyndŵr, the self appointed Prince of Wales and his hundreds of followers launched an assault on Lord Grey's territories burning Ruthin, they continued to Denbigh, Rhuddlan, Flint, Holt, Oswestry and Welshpool, all of which were seen as English towns in Wales. The initial revolt got the attention of the King of England after letters were sent asking for military assistance to combat the Welsh rebels.[30] Much of northern and central Wales went over to Glyndŵr, and from then on, Glyndŵr would stay and hiding and only appear to attack his enemy, his army used effective guerrilla warfare tactics against the English occupying territories in Wales.[9][31]

Welsh rebellion

editOn Good Friday (1 April) 1401, 40 of Glyndwr's men who were led by his cousins, Rhys ap Tudur and Gwilym ap Tudur took Conwy Castle in North Wales. In response, King Henry IV appointed Henry Percy (Hotspur) to bring the country to order. A month later, the King and the English parliament issued an amnesty on 10 March which applied to all rebels with the exception of Owain and his cousins, the Tudurs, however, both the Tudurs were eventually pardoned after they gave up Conwy Castle on 28 May that same year. Hotspur won a battle at Cadair Idris two days later, but that was to be his final service for the King of England, as he retired his command as leader of the English troops after dealing with Glyndŵr.[32][33] During that time in the spring of 1401, Glyndŵr appears in South Wales.[34]

In June, Glyndŵr scored his first major victory in the field at Mynydd Hyddgen on Pumlumon, however, retaliation by Henry IV on Strata Florida Abbey was to follow in October that same year.[35][36] The rebel uprising had occupied all of North Wales; labourers seized whatever weapons they could, and farmers sold their cattle to buy arms. Secret meetings were held everywhere, and bards "wandered about as messengers of sedition". Henry IV heard of a Welsh uprising at Leicester; Henry's army wandered North Wales to Anglesey and drove out Franciscan friars who favoured Richard II. All the while Glyndŵr, who was in hiding, had his estate at Sycarth forfeited by the King to John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset on 9 November 1400.[32] Then, by autumn, Gwynedd and Ceredigion (which temporarily submitted to England for a pardon) and Powys adhered to the rising against the English rule by supporting the rebellion.[34] Glyndŵr's attempts at stoking rebellion with help from the Scottish and Irish were quashed, with the English showing no mercy and hanging some messengers.[citation needed]

As a response to the situation of warfare in Wales, the English Parliament between 1401 and 1402 enacted penal laws against the Welsh, designed to coerce submission in Wales, but the result was to create resentment that pushed many Welshmen into the rebellion.[37] In the same year, Glyndŵr captured his archenemy Baron Grey de Ruthyn. He held him for almost a year until he received a substantial ransom from Henry. In June 1402, Glyndŵr defeated an English force led by Sir Edmund Mortimer near Pilleth (the Battle of Bryn Glas), where Mortimer was captured. Glyndŵr offered to release Mortimer for a large ransom but, in sharp contrast to his attitude to de Grey, Henry IV refused to pay. Mortimer's nephew could be said to have had a greater claim to the English throne than Henry himself, so his speedy release was not an option. In response, Mortimer negotiated an alliance with Glyndŵr and married one of Glyndŵr's daughters.[9][35][38] It is also in 1402 that mention of the French and the people of Flanders helping Owain's daughter Janet, who was negotiating on the continent for her father for two years until 1404.[39]

News of the rebellion's success spread across Europe, and Glyndŵr began to receive naval support from Scotland and Brittany. He also received the support of King Charles VI of France, who agreed to send French troops and supplies to aid the rebellion.[40] In 1403 Glyndwr had amassed an army of 4,000 in his first division, and 12,000 soldiers in total. A Welsh army including a French contingent assimilated into forces mainly from Glamorgan and the Rhondda Valleys region commanded by Owain Glyndŵr, his senior general Rhys Gethin and Cadwgan, Lord of Glyn Rhondda, defeated a large English invasion force reputedly led by King Henry IV himself at the Battle of Stalling Down in Glamorgan.[41][42]

Glyndŵr, facing years on the run, finally lost his estate in the spring of 1403, when Prince Henry as usual marched into Wales unopposed and burnt down Glyndŵr's houses at Sycharth and Glyndyfrdwy, as well as the commote of Edeirnion and parts of Powys. Glyndŵr continued to besiege towns and burn down castles; for 10 days in July that year, he toured the south and southwest of Wales until all of the south joined arms in rebelling against English rule. These actions induced an internal rebellion against the King of England, with the Percys joining the rising.[43][44] It is around this stage of Glyndŵr's life that Hywel Sele, a cousin of the Welsh prince, attempted to assassinate Glyndŵr at the Nannau estate.[45][46]

In 1403, the revolt became truly national in Wales. Royal officials reported that Welsh students at Oxford and Cambridge Universities were leaving their studies to join Glyndŵr,[32][37] and also that Welsh labourers and craftsmen were abandoning their employers in England and returning to Wales. Owain could also draw on Welsh troops seasoned by the English campaigns in France and Scotland. Hundreds of Welsh archers and experienced men-at-arms left the English service to join the rebellion.[47][32]

In 1404, Glyndŵr's forces took Aberystwyth Castle and Harlech Castle,[9] then continued to ravage the south by burning Cardiff Castle. Then, a court was held at Harlech and Gruffydd Young was appointed as the Welsh Chancellor. There had been communication to Louis I, Duke of Orléans in Paris to try (unsuccessfully) to open the Welsh ports to French trade.[48]

Crowning as Prince of Wales

editBy 1404, no less than four royal military expeditions into Wales had been repelled, and Owain had solidified his control of the nation. In 1404, he was proclaimed by his supporters Prince of Wales (Welsh: Tywysog Cymru) and held parliaments at Machynlleth and Harlech.[49] He also planned to build two national universities (one in the south and one in the north), to re-introduce the traditional Welsh laws of Hywel Dda, and to establish an independent Welsh church. There were envoys from other countries including France, Scotland, and the Kingdom of León (in Spain). In the summer of 1405, four representatives from every commote in Wales were sent to Harlech.[50]

Tripartite indenture

editIn February 1405, Glyndŵr negotiated the Tripartite Indenture with Edmund Mortimer and Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland. The Indenture agreed to divide England and Wales among the three of them.[9] Wales would extend as far as the rivers Severn and Mersey, including most of Cheshire, Shropshire and Herefordshire. The Mortimer Lords of March would take all of southern and western England and the Percys would take the north of England.[51][52][d] Although negotiations with the lords of Ireland were unsuccessful, Glyndŵr had reason to hope that the French and Bretons might be more welcoming. He dispatched Gruffydd Yonge and his brother-in-law (Margaret's brother), John Hanmer, to negotiate with the French. The result was a formal treaty that promised French aid to Glyndŵr and the Welsh. The immediate effect seems to have been that joint Welsh and Franco-Breton forces attacked and laid siege to Kidwelly Castle. The Welsh could also count on semi-official fraternal aid from the Duchy of Brittany and from Scotland.[53] Scots and French privateers were operating around Wales throughout Owain's war. Scottish ships had raided English settlements on the Llŷn Peninsula in 1400 and 1401. In 1403, a Breton squadron defeated the English in the Channel and devastated Jersey, Guernsey and Plymouth, while the French made a landing on the Isle of Wight. By 1404, they were raiding the coast of England, with Welsh troops on board, setting fire to Dartmouth and devastating the coast of Devon.[citation needed]

1405 was the "Year of the French" in Wales. A formal treaty between Wales and France was negotiated. On the continent, the French pressed the English as the French army invaded the English Plantagenet Aquitaine.[54] Simultaneously, the French landed in force at Milford Haven in west Wales, burned Haverford West, and attempted to capture Pembroke Castle before they were bought off.[45] The combined forces of French and Welsh took Carmarthen, which Owain had captured in 1403 but lost again. The occupants were given safe passage out, and they burned the town walls. Enguerrand de Monstrelet, a later chronicler gives an uncorroborated account of a march through Herefordshire and on into Worcestershire to Woodbury Hill, ten miles from Worcester. They met the English army and took positions from which they daily and viewed each other from a mile without any major action for eight days. Then, both sides seeming to find engagement too risky, and departed.[55]

Letter to Charles VI of France

editBy 1405, most French forces had withdrawn after politics in Paris shifted towards peace, with the Hundred Years' War continuing between England and France.[56] On 31 March 1406 Glyndŵr wrote a letter to be sent to Charles VI of France in St Peter ad Vincula church at Pennal, hence its naming after the location it was written at. Glyndŵr's letter requested to maintain military support from the French to fend off the English in Wales. Glyndŵr suggested that in return, he would recognise Benedict XIII of Avignon as the Pope. The letter sets out the ambitions of Glyndŵr for an independent Wales with its own parliament, led by himself as Prince of Wales. These ambitions also included the return of the traditional law of Hywel Dda, rather than the enforced English law, establishment of an independent Welsh church as well as two universities, one in south Wales, and one in north Wales.[57] Following this letter, senior churchmen and important members of society flocked to Glyndŵr's banner and English resistance was reduced to a few isolated castles, walled towns, and fortified manor houses.[50]

Glyndŵr's Great Seal and a letter handwritten by him to the French in 1406 are in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. This letter is currently held in the Archives Nationales in Paris. Facsimile copies involving specialist ageing techniques and moulds of Glyndŵr's seal were created by the National Library of Wales and presented by the heritage minister Alun Ffred Jones to six Welsh institutions in 2009.[58] The royal great seal from 1404 was given to Charles IV of France and contains images and Glyndŵr's title –[59]

Latin: Owynus Dei Gratia Princeps Walliae –

"Owain, by the grace of God, Prince of Wales".

Glyndwr referred to himself as the "Prince of Wales" and claimed his "right of inheritance" in these letters[60]

The faltering rebellion

editIn early 1405, the Welsh forces, who had until then won several easy victories, suffered a series of defeats. Glyndŵr's brother, Lord Tudur ap Gruffudd, a commander during the war, died at the Battle of Pwll Melyn in May 1405. English forces landed in Anglesey from Ireland and would over time push the Welsh back until the resistance in Anglesey formally ended toward the end of 1406.[17]

Following the intervention of French forces, battling ensued for years, and in 1406 Prince Henry restored fines and redemption for Welsh soldiers to choose their own fate, prisoners were taken after the battle, and castles were restored to their original owners, this same year a son of Glyndŵr died in battle. By 1408 Glyndŵr had taken refuge in the North of Wales, having lost his ally from Northumberland.[45]

Despite the initial success of the revolution, in 1407 the superior numbers, resources, and wealth that England had at its disposal eventually began to turn the tide of the war, and the much larger and better-equipped English forces gradually began to overwhelm the Welsh. In times of war, the English changed their strategy.[citation needed] Rather than focusing on punitive expeditions as favoured by his father, the young Prince Henry adopted a strategy of economic blockade. Using the castles that remained in English control, he gradually began to retake Wales while cutting off trade and the supply of weapons. By 1407, this strategy was beginning to bear fruit, and by 1408, the English regained Aberystwyth and then marched north Harlech Castle, which also surrendered during the cold winter into 1409. Edmund Mortimer died during the siege, and Owain's wife Margaret along with two of his daughters (including Catrin) and three of Mortimer's granddaughters were captured on the fall of the castle and imprisoned in the Tower of London. They were all to die in the Tower in 1413 and were buried at St Swithin, London Stone.[61] Before his downfall, Glyndŵr was considered the wealthiest of all Welshmen.[62]

Glyndŵr managed to escape capture by disguising himself as an elderly man, sneaking out of the castle and slipping past the English military blockade in the darkness of the night.[citation needed] Glyndŵr retreated to the Welsh wilderness with a band of loyal supporters; he refused to surrender and continued the war with guerrilla tactics such as launching sporadic raids and ambushes throughout Wales and the English borderlands.[63]

Glyndŵr remained free, but he had lost his ancestral home and was a hunted prince. He continued the rebellion, particularly wanting to avenge his wife. In 1410, Owain led a raid into rebel-controlled Shropshire,[9] and in 1412, he carried out one of the final successful raids. With his most faithful soldiers, he cut through the King's men in an ambush in Brecon, where he captured, and later ransomed, a leading Welsh supporter of King Henry, Dafydd Gam ('Crooked David').[64] This was the last time that Owain was seen alive by his enemies, although it was claimed he took refuge with the Scudamore family.[65] In the autumn, Glyndŵr's Aberystwyth Castle surrendered while he was away fighting.[66] But by then things were changing. Henry IV died in 1413, and his son Henry V began to adopt a more conciliatory attitude towards the Welsh. Royal pardons were offered to the major leaders of the revolt and other opponents of his father's regime.[67][page needed] As late as 1414, there were rumours that the Herefordshire-based Lollard leader Sir John Oldcastle was communicating with Owain, and reinforcements were sent to the major castles in the north and south.[citation needed]

On 21 December 1411, the King of England issued pardons to all Welsh except their leader and Thomas of Trumpington (until 9 April 1413, from which Glyndŵr was no longer excepted).[68] Glyndŵr ignored offers of a pardon on many different occasions, his followers continued to be punished for crimes of war until the 1410s. His death was recorded by a former follower in the year 1415.[69]

Disappearance

editNothing certain is known of Glyndŵr after 1412.[9] Despite enormous rewards being offered, he was neither captured nor betrayed. He ignored royal pardons, and it is thought he died in 1415, and certainly by 1417. Adam of Usk, a one-time supporter of Glyndŵr, and writing after the fact, made the following entry in his Chronicle for the year 1415:

"he was buried at night by his followers. But his burial was detected by his opponents; so he was re-buried. But where his body lies is unknown."[70]

Thomas Pennant writes that Glyndŵr died on 20 September 1415 at the age of 61 (which would place his birth at approximately 1354).[71][68]

Glyndŵr may have lived his last days at Kentchurch in south Herefordshire, the home of the Scudamore family.[69] The poet Lewys Glyn Cothi wrote an elegy for Gwenllian, an illegitimate daughter of Glyndŵr, where it was mentioned that at the time of the Welsh War of independence, the whole of Wales was under Glyndŵr's command, with forty dukes as the prince's allies, and that later in life he supported 62 female pensioners.[72]

There are many folk tales of Glyndŵr donning disguises to gain an advantage over opponents during the rebellion,[73] and after his disappearance, there has been persistent speculation that the Welsh religious poet, Siôn Cent, the family chaplain of the Scudamore family,[74] was Owain Glyndŵr in disguise.[75]

Burial

editAlthough the location of his burial is unknown, there has long been speculation where Glyndŵr's final resting place may be. In 1875, the Rev. Francis Kilvert wrote in his diary that he saw the grave of "Owen Glendower" in the churchyard at Monnington on Wye "[h]ard by the church porch and on the western side of it ... It is a flat stone of whitish-grey shaped like a rude obelisk figure, sunk deep into the ground in the middle of an oblong patch of earth from which the turf has been pared away, and, alas, smashed into several fragments."[76][page needed] Another nearby location is usggested by Adrien Jones, the president of the Owain Glyndŵr Society, who stated, "Four years ago we visited a direct descendant of Glyndŵr, a John Skidmore, at Kentchurch Court, near Abergavenny. He took us to Mornington Straddle in Herefordshire, where one of Glyndŵr's daughters, Alice, lived. Mr. Skidmore told us that he (Glyndŵr) spent his last days there and eventually died there... It was a family secret for 600 years, and even Mr Skidmore's mother, who died shortly before we visited, refused to reveal the secret. There's even a mound where he is believed to be buried at Mornington Straddle."[77]

The historian Gruffydd Aled Williams suggests in a 2017 monograph that the burial site is in the Kimbolton Chapel near Leominster, the present parish church of St James the Great which used to be the chapelry of Leominster Priory, based upon a number of manuscripts held in the National Archives. Although Kimbolton is an unexceptional and relatively unknown place outside of Herefordshire, it is closely connected to the Scudamore family.[78]

Issue and descendants

editOwain married Margaret Hanmer, also known by her Welsh name Marred ferch Dafydd, and together they had five or six sons and four or five daughters. Also, Owain had some illegitimate children out of wedlock.[9][68][80][81]

Sons

editAll of Owain and Margaret's sons from their marriage were either taken prisoner and died in confinement, or died in battle and had no issue. Gruffudd was captured in Gwent by Prince Henry, imprisoned in Nottingham Castle, and later taken to the Tower of London in 1410. Maredudd was recorded as communicating with John Talbot and the English Crown on 24 February 1416, and receiving a royal pardon in 1421, but dying a few years later.[68][81]

Daughters

edit- Alice (Alys), m. John Scudamore of Ewyas.

- Jane.

- Janet, m. Sir John De Croft.

- Margaret, m. Sir Richard Monnington.

- Catherine (Catrin) (d. 1413), m. (1) Edmund Mortimer (d. 1409), (2) Roger Mortimer.

Upon Owain's disappearance and death, his eldest (oldest child with descendants) daughter Alice came to be known as the Lady of Glyndyfrdwy and Cynllaith, and heiress de jure of the Principalities of Powys, South Wales and Gwynedd. During 1431, she successfully went to court in Meirionydd to regain her inheritance as the heiress of Sycarth in Glyndyfrdwy against John, Earl of Somerset, who had been granted Owain's forfeited lands by the King of England in 1400. Alice's descendant's married into the Scudamore family and her direct descendant John Lucy Scudamore married the daughter of Harford Jones-Brydges in the early 19th century, and whose daughter in 1852 married the son of Edward Lucas from the Castleshane estate in Ireland. Another daughter, Jane, married Henry, Lord Grey de Ruthin without issue. Then, Janet married into the noble family of Croft Castle in Herefordshire, whose descendants today are titled the Croft Baronets. Whilst Margaret married a knight from Monnington, also in Herefordshire.[32][82]

Illegitimate

editGlyndŵr's illegitimate children with other women included Ieuan, Myfanwy and Gwenllian, whilst it is debated whether his son David was born out of wedlock. Ieuan became Glyndŵr's only male descendant to have children. Like his other illegitimate kin, they remained in Wales and married locally into Welsh families. Gwenllian became the wife of Philip ab Rhys ab Cenarth, and was died near St Harmon in Powys (Radnorshire).[83]

Family poem

editIolo Goch wrote of Glyndŵr's wife, Margaret:[84]

The best of wives.

Eminent woman of a knightly family, Her children come in pairs,

A beautiful nest of chieftains.

Welsh kingdoms lineage

editOwain Glyndŵr's lineage was impeccable. He had claims to royal ancestry from all three of the final ruling royal houses of Wales; Powys (Mathrafal) and Deheubarth (Dinefwr), and Gwynedd (Aberffraw). His claims were clearest for the first two of these:[4][3]

| (Rulers of Powys) | (Rulers of Deheubarth) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bleddyn ap Cynfyn d. 1075 | Rhys ap Tewdwr d. 1093 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maredudd ap Bleddyn d. 1132 | Gruffudd ap Rhys d. 1137 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Madog ap Maredudd d. 1160 | Rhys ap Gruffudd (Lord Rhys) d. 1197 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffudd Maelor I d. 1191 | Gruffudd d. 1201 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor d. 1236 | Owain d. 1235 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffudd Maelor II d. 1269 | Maredudd ab Owain d. 1265 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffudd Fychan I d. 1289 | Owain d. 1275 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Madog Crypl c. 1275 – 1304 | Llywelyn ab Owain d. 1308 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffudd d. 1343 | Tomos d. 1343 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffudd Fychan II c. 1330 - 1369 | Elen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owain Glyndŵr c. 1354 – 1415 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gwynedd ancestry

editAs well as being a direct genealogical descendant of the final ruling monarchs of Powys and Deheubarth, Owain Glyndwr's ancestors were also descended from the Welsh medieval Kingdom of Gwynedd, descended from the Gwynedd King Gruffudd ap Cynan (d. 1137), via his great-grandmother Gwenllïan.[9][85] However, some sources claim that another ruler of Gwynedd, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn I, The Great d. 1240), Gruffudd ap Cynan's great-grandson, was Glyndwr's nearest Gwynedd royal ancestor.[6] Elsewhere, a third suggestion is that he was descended from Llywelyn II, Prince of Wales (Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, d. 1282), who was Llywelyn I's grandson, and also the penultimate Prince of Gwynedd from the final generation of the Aberffraw rulers in Wales before his brother, Dafydd III.[5][86] Yet historians note that Llywelyn II's only recorded child was a daughter, Gwenllian, who died in 1337 without issue.[87][88] Professor John Edward Lloyd said: "There is no evidence that Llywelyn had any daughter but Gwenllian, born in the last year of his life and after his death confined for the rest of her days as a nun of the order of Sempringham".[89] Lloyd's assessment has been repeated by other Welsh historians.[90][91] The claim to Gwynedd heritage through his great grandmother would have been strengthened, however, by the recognition that "the direct male line of Gwynedd had undeniably become extinct in 1378. Its last representative was Owain Lawgoch."[92]

Banners and coat of arms

edit-

Owain Glyndŵr's coat of arms. It demonstrates his lineage from the princes of Gwynedd, whose flag in the 13th century had been four passive lions. It was also used by pretender Prince of Wales, Owain Lawgoch.[60][e]

-

Arms assigned Owain Glyndŵr in A Tour in Wales by Thomas Pennant (1726–1798), which chronicles the three journeys he made through Wales between 1773 and 1776.[71]

Legacy

editIn Welsh culture Glyndwr has been perceived to have a mythical status alongside the likes of other medieval Kings, such as Cadwaladr, Cynon ap Clydno and King Arthur as a folk hero awaiting a call to return and liberate his people in the classic Welsh mythical role– "Y Mab Darogan" ("The Foretold Son"). The myth was that one day after a thousand years of servitude under English rule, a 'Son of Prophecy' would return the Welsh people as rulers of the island of Great Britain.[96][97] Also, in Welsh folklore, the name Owain has been connected to a legend of the 'son of destiny'. His claim as the Prince of Wales was similar to that of another distant relative from the Gwynedd dynasty. It was another Owain, Lawgoch (Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri) who proclaimed his patrimony a few decades earlier, when he attempted to regain his family stature with aid from the King of France in a Franco-Welsh alliance from the late 1360s, until his assassination.[98]

Modern legacy

edit- Glyndŵr was described by Fidel Castro as the first effective guerrilla leader. It has been suggested that Castro, who may have kept books about the Welshman, and Che Guevara copied some of Glyndŵr's methods in the Cuban Revolution.[100][page needed][101]

- During the First World War, the prime minister David Lloyd George unveiled a statue to Glyndŵr in Cardiff City Hall.[102] A statue of Glyndŵr by the sculptor Simon van de Put was installed in The Square in Corwen in 1995, and in 2007 it was replaced with a larger equestrian statue by Colin Spofforth.[103]

- Glyndŵr came second to Aneurin Bevan in the 100 Welsh Heroes poll of 2003/2004.[104] Stamps were issued with his likeness in 1974 and 2008,[105] and streets, parks, and public squares were named after him throughout Wales. There is a campaign to make 16 September (Owain Glyndŵr Day), the date Glyndŵr raised his standard, a public holiday in Wales, including by Dafydd Wigley in 2021.[106]

- RGC 1404 (Rygbi Gogledd Cymru/North Wales Rugby) rugby union team is named in honour of the year Owain Glyndŵr was crowned Prince of Wales.[107]

- A road in Aberystwyth was renamed as "Owain Glyndwr Square".[99]

- To celebrate the 600th year anniversary of Glyndŵr's life, a monument was erected in Machynlleth in the grounds of Plas Machynlleth.[99]

Meibion Glyndŵr

editGlyndŵr is now remembered as a national hero and numerous small groups have adopted his symbolism to advocate independence for Wales or Welsh nationalism. For example, during the 1980s, a group calling itself Meibion Glyndŵr ("the Sons of Glyndŵr") claimed responsibility for the burning of English holiday homes in Wales.[108]

Literature

edit- After Glyndŵr's death, there was little resistance to English rule. The Tudor dynasty saw Welshmen become more prominent in English society. In Henry IV, Part 1, Shakespeare portrays him as Owen Glendower (the name has since been adopted as the anglicised version of Owain Glyndŵr),[109] wild and exotic; a man who claims to be able to "call spirits from the vasty deep", ruled by magic and tradition in sharp contrast to the more logical but highly emotional Hotspur.[110] Glendower is further noted as being "not in the roll of common men" and "a worthy gentleman,/Exceedingly well read, and profited/ In strange concealments, valiant as a lion/And as wondrous affable and as bountiful/As mines of India."[111] His enemies describe him "that damn'd magician", which was in reference to having the weather on his side in battle.[112]

- It was not until the late 19th century that Glyndŵr's reputation was revived, when the Cymru Fydd ("Young Wales") movement recreated Glyndŵr as the father of Welsh nationalism.[113]

- Glyndŵr later acquired mythical status as the hero awaiting a call to return and liberate his people.[97][114] Thomas Pennant, in his Tours in Wales (1778, 1781 and 1783), searched out and published many of the legends and places associated with the memory of Glyndŵr.[71] Glyndŵr has been featured in a number of works of modern fiction, including most notably John Cowper Powys's novel Owen Glendower (1941),[115][page needed] and Edith Pargeter's 1972 publication A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury.[116][page needed]

- A highly fictionalized Glyndŵr is featured in the popular YA book series The Raven Cycle by Maggie Stiefvater as Owen Glendower. In the series, which takes place in the Shenandoah Valley, characters believe that Glyndŵr's body was brought from Wales to Virginia after his death, and that whoever can "wake" him will be granted a wish.[117]

Namesakes

edit- The Owain Glyndwr Hotel in Corwen is a historic 18th century coaching inn.[118]

- The Owain Glyndŵr pub in Cardiff, briefly named Owen Glendower was named in his honour.[99]

- The waymarked, 132-mile long-distance footpath Glyndŵr's Way runs through Mid Wales near to his homelands.[119]

- At least two ships and two locomotives have been named after Glyndŵr:

- In 1808, the Royal Navy launched a 36-gun fifth-rate frigate,HMS Owen Glendower. She served in the Baltic Sea during the Gunboat War where she participated in the seizure of Anholt Island, and then in the Channel. Between 1822 and 1824, she served in the West Africa Squadron (or "Preventative Squadron") chasing down slave ships, capturing at least two;[120]

- Owen Glendower, an East Indiaman, a Blackwall frigate built in 1839;[121]

- In 1923, a 2-6-2T Vale of Rheidol locomotive was named after Glyndŵr. The locomotive is still operational and was one of a few used by British Rail until it was privatised;[122][123]

- 70010 Owen Glendower, renamed Owain Glyndŵr, built in 1951 at the Crewe Works, it was withdrawn in June 1965. The train was a British Railways Standard Class 7 mixed-traffic steam locomotive.[124]

- In 2002, a plaque was unveiled near the Tower of London to commemorate Glyndwr's Glyndŵr Catrin who died there with her children.[99]

- From 2008 to 2023, Wrexham University was known as (Wrexham) Glyndŵr University in his honour. Despite dropping the name in 2023, the university maintains links with the Owain Glyndŵr Society for one of its annual graduate awards.[125]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Gower 2012, p. 134.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 14.

- ^ a b Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 11, 13

- ^ a b Lloyd 1881, pp. 194, 197, 212

- ^ a b Burke 1876, pp. 7, 43, 51, 97

- ^ a b Panton 2011, p. 173

- ^ Connolly 2021, p. 205.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 15-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pierce 1959

- ^ Evans 2016, p. 15.

- ^ Henken 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Penberthy 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Davies 1995, p. 6,22,113.

- ^ Carr 1977.

- ^ a b Tout 1901, p. 427

- ^ a b Davies 1995

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Tout 1901, p. 428

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Johnston 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Williams 2011, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Allday 1981, p. 51.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Mortimer 2013, pp. 226-.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Skidmore 1978, p. 24.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 29–32, 35.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e Tout 1901, p. 429

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Tout 1901, p. 429-430

- ^ a b Tout 1901, p. 430.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 47–51.

- ^ Lloyd 1881, p. 215.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 32, 91.

- ^ Lloyd 1881, p. 250.

- ^ Morgan 1911, pp. 418–425.

- ^ Tout 1901, p. 431.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Tout 1901, p. 433

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 62, 130, 142.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Tout 1901, p. 432.

- ^ Davies 1995, pp. 163–164.

- ^ a b Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 195.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 91–95.

- ^ Davies 1995, p. 194.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 95.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 102–104.

- ^ National Library of Wales n.d.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 101.

- ^ a b Siddons 1991, p. 287.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 123–124, 127, 133–134.

- ^ Carr 1995, pp. 108–132.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 129–132.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 135.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Chapman 2015.

- ^ a b c d Tout 1901, p. 434

- ^ a b Turvey 2010, pp. 122/3

- ^ Davies 1995, p. 327.

- ^ a b c Pennant 1784, p. 393

- ^ Lloyd 1881, p. 257.

- ^ Bradley 1901, p. 280.

- ^ Lewis 1959.

- ^ Gibbon 2007

- ^ Plomer 1986.

- ^ BBC 2004.

- ^ Williams 2017.

- ^ Bentley 2002.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 13.

- ^ a b Lloyd 1881, p. 252

- ^ Lloyd 1881, pp. 252–257.

- ^ Lloyd 1881, pp. 252, 257–258.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 12

- ^ Turvey 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Pierce 1959b.

- ^ Messer 2017.

- ^ Lloyd 1919, p. 128.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 154.

- ^ Maund 2011.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 12.

- ^ Scott-Giles 1967, p. 74.

- ^ de Usk & Thompson 1904, p. 238.

- ^ Ramsay 1892, p. 43.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, pp. 144/5.

- ^ a b Davies, Jenkins & Baines 2008, p. 635.

- ^ Turvey 2010, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b c d e Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 152

- ^ Roberts 2017.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Davies 1995, p. v.

- ^ Van Tilburg 2021.

- ^ 100 Welsh Heroes 2004.

- ^ BBC 2008.

- ^ Wigley 2021.

- ^ BBC 2010.

- ^ Brooke 2018, p. 60.

- ^ Shakespeare 1998, p. 288.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 146.

- ^ Shakespeare 1998, 3.1.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 142.

- ^ Arron 2013.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 137.

- ^ Powys 1941.

- ^ Parteger 1989.

- ^ Stiefvater 2015.

- ^ Cadw n.d.

- ^ Davies & Morgan 2009, p. 153.

- ^ Burke 2011.

- ^ Royal Museums Greenwich n.d.

- ^ Johnson 2020.

- ^ Reading & Reading 2023.

- ^ Langston 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Wrexham University 2023.

Notes

edit- ^ 1400-1409 could be considered the dates of his reign considering the year of his disappearance.

- ^ The Scudamore family oral tradition has it that he died and was buried in Monnington Straddle, Herefordshire on St. Matthew's Day (21/9). However, more modern sources dispute this, instead raising various alternative locations to the original burial. Some common locations raised are: the church of Saints Mael and Sulien at Corwen (close to his home), his estate in Sycharth, or on one of the estates of his daughters' husbands, such as Kentchurch in South Herefordshire, and also another location in the Monnington area.

- ^ (Illustration from Hutchinson's History of the Nations, 1915)

- ^ R. R. Davies noted that certain internal features underscore the roots of Glyndŵr's political philosophy in Welsh mythology: in it, the three men invoke prophecy, and the boundaries of Wales are defined according to Merlinic literature.

- ^ Coat of Arms: Quarterly or and gules, four lions rampant armed and langued azure counterchanged. The banner was modified from the Gwynedd banner/flag of Prince Llywelyn II.[93]

Bibliography

edit- Arron, Jane (5 June 2013). "'A Nation Once Again': Owain Glyndŵr and the 'Cymraec Dream' of Anglophone Welsh Victorian Poets". walesartreview.org.

- Allday, D. Helen (1981). Insurrection in Wales: the rebellion of the Welsh led by Owen Glyn Dwr (Glendower) against the English Crown in 1400. Lavenham: Terence Dalton. p. 51. ISBN 0-86138-001-0.

- "Glyndŵr's burial mystery 'solved'". news.bbc.co.uk. 6 November 2004.

- "New Owain Glyndwr stamp unveiled". BBC News. 29 February 2008.

- "North Wales summon Owain Glyndwr's spirit in revamp". bbc.co.uk. 6 January 2010.

- Bentley, G. E. (27 February 2002). "Blake's Visionary Heads: Lost Drawings and a Lost Book". In Fulford, T. (ed.). Romanticism and Millenarianism. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 183–205. ISBN 978-0-312-24011-0.

- Bradley, A.G. (1901). Owen Glyndwr and the Last Struggle for Welsh Independence. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Brooke, Nick (17 April 2018). Terrorism and Nationalism in the United Kingdom: The Absence of Noise. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-76541-9.

- Burke, Bernard (1876). The Royal Families of England, Scotland (PDF). Pall Mall, London: Harrison.

- Burke, Steven (April 2011). Humphreys, Cathy (ed.). "The Reality of Travelling the African Coast: Midshipman Binstead on chasing". New Histories. 2 (6). Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- "Full Report for Listed Buildings". cadwpublic-api.azurewebsites.net. Cadw, Welsh Government. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- Carr, A.D. (1995). "Rebellion and Revenge". Medieval Wales, British History in Perspective, Chapter 46: Rebellion and Revenge. Palgrave, London. pp. 108–132. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-23973-3_6. ISBN 9781349239733.

- Chapman, Adam (2015). Welsh soldiers in the Later Middle Ages. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1783270316.

- Carr, A.D. (1977). "A Welsh Knight in the Hundred Years War: Sir Gregory Sais". Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 1977: 40–53. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- Connolly, Sharron Bennett (2021). Defenders of the Norman Crown : Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey. Pen & Sword History. ISBN 9781526745323.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, Menna, eds. (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0708319536.

- Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin Books. p. 195. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- Davies, R. R. (1995). The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 293–324. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198205081.003.0012. ISBN 978-0198205081. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Davies, R. R.; Morgan, Gerald (2009). Owain Glyn Dŵr: Prince of Wales. Ceredigion: Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-1-84771-127-4.

- de Usk, Adam; Thompson, Edward Maunde (1904). Chronicon Adae de Usk, A.D. 1377–1421. London : H. Frowde. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Dillon, Paddy (7 May 2024). Walking Glyndwr's Way: A National Trail through mid-Wales. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-78765-068-8.

- Evans, David (2016). "Owain Glyndŵr". Owain Glyndŵr.

- Gibbon, Alex (2007). The mystery of Jack of Kent & the fate of Owain Glyndŵr. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-3320-9.

- Gower, Jon (9 February 2012). The Story of Wales. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-1710-2.

- Henken, Elissa R. (1996). National Redeemer: Owain Glyndŵr in Welsh Tradition. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8349-3.

- Johnson, Peter (30 April 2020). The Vale of Rheidol Railway: The Story of a Narrow Gauge Survivor. Pen and Sword Transport. ISBN 978-1-5267-1808-2.

- Iolo Goch poems. Translated by Johnston, Dafydd. Llandysul, Wales: Gomer. 1993. ISBN 978-0-86383-707-4. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- Langston, Keith (1 January 2012). British Steam BR Standard Locomotives. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84563-146-8.

- Lewis, Henry (1959). "Sion Cent (1367? - 1430?), poet". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Lloyd, Jacob Youde W. (1881). "6". The History of the Princes. Vol. 1. Great Queen Street, London: T. Richards Printer.

- Lloyd, J.E. (1919). "Owain Glyn Dŵr : His Family and Early History". Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 1918-1919: 128–145. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- Maund, Kari (24 October 2011). The Welsh Kings: Warriors, Warlords and Princes. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7392-5.

- Messer, Danna R (2017). "Eleanor de Montfort (c. 1258–1282), princess and diplomat". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Mortimer, Ian (2013). The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King. Random House. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-1-4070-6633-2.

- "Pennal letter". library.wales.

- Panton, Kenneth (2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press.

- Parteger, Edith (1989) [1972]. A Blood Field by Shrewsbury. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0747233667.

- Penberthy, David (June 2010). "Owain Glyndwr and his uprising – Interpretation Plan" (PDF). Cadw - Welsh Government. Cymdeithion Siân Shakespear Associates. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- Pennant, Thomas (1784). A tour in Wales. p. 393. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "Owain Glyndwr (c. 1354–1416), 'Prince of Wales'". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "LLYWELYN ap GRUFFYDD ('Llywelyn the Last,' or Llywelyn II), Prince of Wales (died 1282)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Plomer, William (1986). Kilvert's Diary: 1870–1879: Life in the English Countryside in Mid-Victorian Times. D.R. Godine. ISBN 087923637X.

6 April 1875

- Powys, John Cowper (1941). Owen Glendower. Simon & Schuster.

- Ramsay, James H. (1892). The scholar's history of England . London: H. Milford. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Reading, Brian; Reading, Ian (15 February 2023). Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railways: The Late 1940s to Late 1960s. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-3981-0013-8.

- Roberts, Emrys (2017). Highlights From Welsh History. Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-1-78461-482-9.

- "The "Owen Glendower", East Indiaman, 1000 Tons. (Entering Bombay Harbour)". The Collections. Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Scott-Giles, Charles Wilfrid (1967) [1929]. The Romance of Heraldry (Revised ed.). J.M. Dent & Sons. p. 74. ISBN 0900455284.

- Shakespeare, William (1998). Bevington, David (ed.). Henry IV, Part 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283421-8.

- Siddons, Michael Powell (1991). The development of Welsh heraldry v I. National Library of Wales. ISBN 978-0-907158-51-6.

- Skidmore, Ian (1978). Owain Glyndŵr: Prince of Wales. Swansea: Christopher Davies. p. 24. ISBN 0715404725.

- Stiefvater, Maggie (2015). The Raven King (The Raven Cycle, Book 4). Scholastic Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0545424981.

- Tout, T.F. (1901). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 21. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Turvey, Roger (2010). Twenty-One Welsh Princes. Conwy: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 9781845272692.

- Van Tilburg, Kees (2021). "Equestrian statue of Owain Glyndwr in Corwen UK".

- Wigley, Dafydd (16 September 2021). "Glyndŵr Day is worthy of a new national holiday". The National. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Williams, Gruffydd Aled (2017). The Last Days of Owain Glyndŵr. Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-1-7846-146-38. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Williams, Phil (2003). The Psychology of Distance: Wales: One Nation. Institute of Welsh Affairs. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-86057-066-7.

- Williams, Aled (2011). "The medieval Welsh poetry associated with Owain Glyndwr". British Academy Review (17 ed.).

- Wolcott, Darrell (n.d.). "Owain Glyndwr ancestry". ancientwalesstudies.org.

- "Prifysgol Wrecsam/Wrexham University unveils rebrand and new name". Wrexham University. 25 September 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- "100 Welsh Heroes". 100welshheroes. 2004. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

Further reading

edit- Burton, Robert (1730). The history of the principality of Wales. : In three parts. Paternoster Row, London. – A history of the Principality of Wales at Google Books

- Latimer, Jon; Murray, John (2001). Deception in War. pp. 12–13.

- Lowe, Walter Bezant (1912). The Heart of Northern Wales. Vol. 1. pp. 205–207. – The Heart of Northern Wales, p. 205, at Google Books

- Lloyd, J. E. (1931). Owen Glendower. Oxford University Press.

- Morgan, Owen (1911). A history of Wales from the Earliest Period: Including Hitherto Unrecorded Antiquarian Lore. – A History of Wales at Google Books

- Moseley, Charles (1 August 1999). Burke's Peerage & Baronetage (106 ed.). pp. 714, 1295. ISSN 0950-4125.

External links

edit- "Canolfan & Senedd-Dŷ Owain Glyndŵr (Owain Glyndŵr's Parliament & Centre)". canolfanowainglyndwr.org.

- "The Owain Glyndŵr Society". owain-glyndwr.wales.