Charles Lewis Blood (September 8, 1835 – September 27, 1908; alias C. H. Lewis et al.) was an American con artist and self-styled physician who operated in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago. He produced a patent medicine treatment known as "oxygenized air", which he promoted as a cure for catarrh, scrofula, consumption, and diseases of the respiratory tract.[1][2]

C. L. Blood | |

|---|---|

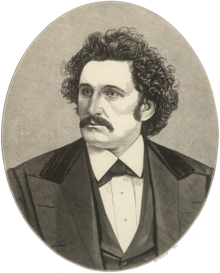

C. L. Blood, ca. 1875 | |

| Born | Charles Lewis Blood September 8, 1835 Groton, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | September 27, 1908 (aged 73) Manhattan, New York |

| Other names | C. H. Lewis, C. B. Lewis, C. Lewis Blood, H. J. Hartwell, et al. |

| Occupation(s) | Con artist, physician |

Career

editCharles Lewis Blood was born 1835 in Groton, Massachusetts;[3] he claimed to be the son of Dr. Louis Blood, a physician, though this was correctly believed at the time to be a fabrication.[4] His father was actually Lewis Blood (1805–1887), a successful farmer, timber dealer, contractor and prominent citizen in Ayer (formerly Groton Junction), Massachusetts.[5][6] His medical credentials were likewise in question—though he styled himself "Dr. C. L. Blood" or "C. L. Blood, M.D." and authored a book on medicine, he was widely supposed to be a con artist with no legitimate claim to any medical degree.[7][8][9] His notoriety was said to be national, albeit distributed among a variety of aliases.[4]

Around 1865, Blood moved from Philadelphia to Boston, where he established an office in the old Congregational Library building at 12 Chauncy Street. He began promoting his medical services via full-page newspaper advertisements, as well as advertising sheets which he distributed to the surrounding country. Around this time he also developed an interest in Gardner Quincy Colton's use of "laughing gas", or nitrous oxide.[4][9] Blood learned the manner of its manufacture and thereafter claimed the invention as his own, rebranding it as "oxygenized air" and touting it as a cure for diseases of the throat and lungs.[2][4]

Blood's business flourished, which enabled him to move into better quarters at 119 Harrison Avenue. He extensively advertised his ability to cure all diseases of the blood and lungs by means of his "air", which he administered at his practice.[2][9] A page would answer the calls of visitors at his door and usher them into elegantly furnished reception areas to await the appearance of Blood from his consultation room. Blood employed numerous shills to maintain the appearance of doing an immense business, which artifice he used to lure investors. To these he offered contracts securing the exclusive right to resell his "air" in various states and territories.[4][9][10]

Blood left Boston some time after 1867, shifting his activities to various cities in the Northeast and Midwest. He was known to maintain practices in New York City around 1875,[1] in Chicago from 1875 to 1876,[9] in Philadelphia in 1883,[8] and again in Boston in the late 1880s.[9] He died aged 73 in Manhattan on September 27, 1908, after an illness lasting eleven weeks.[11][12] In a short obituary in his hometown Ayer, Massachusetts newspaper, it was reported that Blood "had lived in New York city twelve years, where he was in a manufacturing business."[12] His remains were transported to Ayer where he was buried in the family plot in Woodlawn Cemetery on October 1, a funeral having taken place the day before in the Lewis Blood house in Washington Street.[12] Perhaps in view of the shame brought upon the Bloods by Charles' sordid past, his widow and four surviving sisters chose not to add his name to the family memorial.

Criminal activities and allegations

editBlackmail

editWhile in Boston, Blood gained a rival in the person of a certain Dr. Jerome Harris, who also applied nitrous oxide but under the name of "super-oxygenized air". Unlike Blood, Harris was a trained physician, albeit one who traded on Blood's popularity by operating his practice from Blood's old quarters on Chauncy Lane.[4] One day in the winter of 1866–67, Harris was visited by a Mr. Carvill of Lewiston, Maine who had a bronchial complaint and specifically requested Harris's "super-oxygenized air" treatment. The air was administered, and in a moment Carvill began frothing at the mouth and rolling on the floor, apparently in a fit, his contortions lasting about an hour. Finally Harris sent his patient home, whereupon the latter called for the services of his own physician, who turned out to be Blood.[4][9]

The next day the newspapers described Harris's supposed "poisoning" of Carvill by the administering of "super-oxygenized air", and the subsequent relief afforded the patient by Blood. Blood saw to it that the public were kept apprised of the supposedly continual improvement of the patient under his care, and reassured of the efficacy and harmlessness of his own "oxygenized air". Carvill subsequently brought suit against Harris, which served to maintain the media publicity against Harris's rival treatment. Though Harris was anxious to settle with Carvill, his legal counsel advised him not to pay, claiming it was a blackmail scheme. The case finally fell through, but Harris was frightened and left the city, after which Blood's business prospered.[4][9]

In May 1884, Blood was brought into the public eye again in Boston by reason of his arrest for blackmailing Ernest Weber, a local musician. The previous month, Blood had begun courting a woman by the name of Jennett Nickerson. He procured from her, allegedly by force, an affidavit to the effect that she had been ruined under promise of marriage by Weber, and that Weber had furthermore employed a physician to perform an abortion which had nearly cost her her life. A confederate of Blood exhibited the affidavit, together with correspondence between Weber and Nickerson, in a lawyer's office in the presence of Weber. Weber was threatened with criminal prosecution unless he paid $4000. Weber consulted with the police, who arrested Blood and his confederate; after a sensational trial both men were convicted of blackmailing and sentenced to several years in prison.[9]

Tax evasion

editSome time after his involvement with Dr. Harris, Blood got into trouble with the federal government for failure to properly stamp his patent medicines. Soon thereafter he disappeared from Boston, his last appearance being made in the custody of two deputy U.S. marshals. He reappeared some time later in Philadelphia, having somehow extricated himself from the situation.[9]

Fraud and misdemeanors

editDuring his first residence in Boston, Blood succeeded in conning Humphrey Cummings, an experienced businessman from Wellesley, Massachusetts, into providing him with $4500 in capital. The dividends Cummings received from the partnership were no more tangible or valuable than the atmospheric air Blood was peddling, and after a short time he demanded that Blood return the money he had advanced. Cummings was never repaid, and about a year later he died, broken down by the loss of his fortune.[4]

In 1880, Blood published A Century of Life, Health and Happiness, a compendium of medical information for the home. In January 1883, an investor by the name of Charles Baker alleged that Blood had defrauded him of $210 when the author failed to provide sundry copies of his book. A warrant was issued for Blood's arrest, who at the time was already wanted by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for various misdemeanors.[8] Blood was captured in Philadelphia and turned over to the Massachusetts State Police on a charge of defrauding by false pretences.[4]

Murder of Hiram Sawtelle

editIn February 1890, Blood was implicated in the murder of Hiram Sawtelle, a Boston fruitseller. Isaac Sawtelle, Hiram's brother, had recently been released from prison after securing, at great expense, a pardon for his rape convictions. The destitute Isaac moved in with Hiram and their mother, and soon entered into a dispute with them concerning the estate left by his deceased father. Isaac was desperate to gain control of the property, which was held in his mother's name but managed by Hiram.[13]

According to Isaac, Blood, whom he had met in prison, offered to engineer Hiram's cooperation for a fee of $500. A third man, another former convict by the name of Jack, was then brought into the plan. Isaac abducted Hiram's daughter Marion and then used her to lure Hiram to a secluded camp near Springvale, Maine. There it was planned that Blood and Jack would force him to sign over the property.[14] For whatever reason, the enterprise did not go according to plan. Hiram was shot four times, undressed, decapitated, and partly dismembered. The headless body was buried in a shallow grave just across the state line in New Hampshire.[15]

On discovering her husband's disappearance, Hiram's wife reported to the police her suspicion that he had been murdered by Isaac. A search was organized, and Hiram's body was discovered by investigators some ten days after the crime. Isaac had left Boston but was eventually captured in Rochester, New Hampshire. When he was arrested he had in his possession two train tickets to Montreal; it was speculated that the second ticket was for Blood. Blood's picture was circulated in the Boston newspapers, where it was recognized by two hoteliers from Dover, New Hampshire, whom Blood had approached for accommodation around the time of the murder. One of the hoteliers reported that Blood had been carrying two bundles, one done up in wrapping paper and apparently containing clothes, and the other wrapped in newspaper and "about the size of a man's head".[9]

By April 1890, Isaac Sawtelle had been charged with conspiracy and with the murder of Hiram, and was awaiting trial. On April 13, he released a confession through his attorney, admitting that he had plotted to intimidate Hiram into signing over the property but denying that he planned or had any part in the murder. Isaac instead held that he rendezvoused with Hiram at the appointed camp, where they were met by Jack as planned. Jack then led Hiram away on the pretence of taking him to Marion, while Isaac remained behind. Isaac claimed to have had no inkling that his brother had been murdered until the morning of his arrest, when he received a letter from Blood that read, "Your brother had to be put out of the way. Let each look out for himself."[14] Isaac later asserted that Blood had owed Hiram a considerable sum of money, implying that Blood had dispatched Hiram to escape the debt.[9]

Despite Isaac's jailhouse confessions and the hoteliers' statements, Blood was never questioned by police. Hiram's widow denied that Blood had any dealings with Hiram, though she did aver that he was a frequent guest of Isaac.[9] At trial, Isaac changed his story, confessing that he had shot Hiram himself and demoting Blood's role in the conspiracy to preparation of the legal instruments for Hiram to sign.[15] Isaac was convicted and sentenced to death,[16] after which he recanted his previous confession and once again laid full responsibility for the murder on Blood:

- Dr. Blood is the man who is responsible. Some time it will be known, a deathbed repentance, perhaps, and when all is known it will be found that I am innocent of anything to do with the murder. I have accused him; I accuse him now. If he had come forward I would have accused him to his face. But why didn't he appear? He didn't dare to; he didn't dare to face me. Now that I am practically dead he can do what he pleases. He has had a chance to establish and prove an alibi, while I have been in jail, tied hand and foot… Blood was responsible in every way. I do not mean to say that he killed Hiram—that he fired the shots which caused his death—but I do mean that he knew of it and was responsible for it.[17]

Isaac Sawtelle died of natural causes on December 26, 1891, shortly before his scheduled execution.[18]

Personality and appearance

editContemporary reports describe Blood as being about six feet (180 cm) tall, well built, and erect in carriage. He was said to be handsome, with a fresh, fair complexion and small, sparkling black eyes; he looked much younger than he claimed to be. He sported a full mane of brown or black hair, which he wore curled. His personality was described as vain but affable; he was known as a finely dressed masher who handed out visiting cards bearing his photograph. When not engaged in his office he would often be found loitering on the streetcorner below.[4][7][9]

Cultural references

editA fictionalized version of Blood appears as an important supporting character the 1991 role-playing video game Ultima: Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams. The game's manual describes him as "a concerned and able doctor" who was nonetheless "reviled by the medical establishment of the 1870s for espousing the curative powers of his creation".[19] Blood accompanies the protagonist and his fellow adventurers on a rescue mission to Mars and, throughout the game, competently heals their injuries, radiation poisoning, and hypoxia, sometimes with the aid of his oxygenized air.[20]

Another fictionalized but historically based version of Blood is featured in a standalone short story by suspense author Christie Stratos called, "The Wrong House." The story includes what is historically accurate and what is fictionalized at the very end.

Bibliography

edit- C. L. Blood. A Century of Life, Health and Happiness: Or, A Gold Mine of Information. A Cyclopedia of Medical Information for Home Life, Health and Domestic Economy. 1880.

References

edit- ^ a b Blood, C. L. (1875). "Persecution of New Ideas". Asher & Adams' New Columbian Rail Road Atlas and Pictorial Album of American Industry. Asher & Adams. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Oxygenized Air". Lewiston Evening Journal. May 1, 1867. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Massachusetts Town & Vital Records, 1620–1988

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "A Wily Doctor". The Boston Weekly Globe. January 30, 1883. p. 8. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Sargent, William M. (1902). Some of the Leading Industries, Principal Buildings and Prominent Citizens – Town of Ayer. Ayer, Massachusetts. pp. 106–108. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mss. papers of C. L. Blood's sister, Mary Jane Blood Clough (1837–1918), in the Blood/Clough family archives in possession of Mr. G. R. Urquhart.

- ^ a b "Mrs. Christiancy". The Cincinnati Enquirer. January 8, 1881. p. 1. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Blood's Victims Turning up". The Times. January 24, 1883. p. 1. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "A Man of Ominous Name". The Inter Ocean. February 19, 1890. p. 1. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Alleged Forgery". The Inter Ocean. September 28, 1877. p. 8. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795–1949; Certification number 29310

- ^ a b c "Charles Lewis Blood ..." (PDF). Turner's Public Spirit. October 3, 1908. p. 5. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ George Vedder Jones (May 27, 1951). "The Case of the Prodigal Son". The Milwaukee Sentinel. pp. 20, 24. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ a b "Confession by Isaac Sawtelle". Chicago Tribune. April 14, 1890. p. 6. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Crime of Cain". The Morning Call. December 17, 1891. p. 2. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Sawtelle Must Hang". The Day. December 26, 1890. p. 7. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Says Dr. Blood is Responsible". Chicago Tribune. December 31, 1890. p. 1. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ "Sawtelle Dead". Lewiston Evening Journal. December 26, 1891. p. 16. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Spector, Warren (1991), "Time Travel: Use of the Orb of the Moons", Ultima: Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams, Austin, TX: Origin Systems, p. 6

- ^ Spector, Warren; Miller, Beth (1991). Ultima: Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams: Clue Book: The Lost Notebooks of Nellie Bly. Austin, TX: Origin Systems.

External links

edit- A Century of Life, Health and Happiness, or, A Gold Mine of Information, by C. L. Blood, M.D., 1880, at Internet Archive

- Murder by Gaslight: Cain and Abel

- Dr. C. L. Blood at The Codex of Ultima Wisdom, a wiki for Ultima