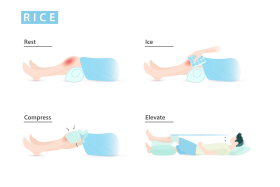

RICE is a mnemonic acronym for the four elements of a treatment regimen that was once recommended for soft tissue injuries: rest, ice, compression, and elevation.[1] It was considered a first-aid treatment rather than a cure and aimed to control inflammation.[2] It was thought that the reduction in pain and swelling that occurred as a result of decreased inflammation helped with healing.[1] The protocol was often used to treat sprains, strains, cuts, bruises, and other similar injuries.[3] Ice has been used for injuries since at least the 1960s, in a case where a 12-year-old boy needed to have a limb reattached. The limb was preserved before surgery by using ice. As news of the successful operation spread, the use of ice to treat acute injuries became common.[4]

| RICE | |

|---|---|

Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation |

The mnemonic was introduced by Dr. Gabe Mirkin in 1978.[5] He withdrew his support of this regimen in 2014 after learning of the role of inflammation in the healing process.[6] The implementation of RICE for soft tissue injuries as described by Dr. Mirkin is no longer recommended, as there is not enough research on the efficacy of RICE in the promotion of healing.[2] In fact, many components of the protocol have since been shown to impair or delay healing by inhibiting inflammation.[2][3][7] Early rehabilitation is now the recommendation to promote healing.[3][8] Ice, compression, and elevation may have roles in decreasing swelling and pain, but have not shown to help with healing an injury.[2][7][9]

There are different variations of the protocol, which may emphasize additional protective actions. However, these variations similarly lack sufficient evidence to be broadly recommended.[9] Examples include PRICE, POLICE, and PEACE & LOVE.[9][10][11][12]

Primary four terms

editRest

editRest refers to limiting the use of an injured area. It was once recommended to rest an injury for up to 2 days or until it was no longer painful to use.[1] It was intended to reduce inflammation and to prevent further injury.[2] Blood supply is an important component of inflammation. By resting an injury, blood flow to the area is reduced, which reduces the swelling and pain associated with inflammation.[13] The early stages of healing involve microscopic scaffolding that is built upon to repair an injury. These scaffolds are relatively weak until reinforced by later stages of healing.[14] Early and aggressive movement could potentially disrupt the scaffolds, delaying healing or worsen an existing injury.[2]

Although rest may provide some benefit immediately after an injury, returning to movement early has been shown to be better at reducing pain and encouraging healing.[3][8]

Ice

editIce being applied to a leg propped on a pillow for elevation |

Ice refers to the application of cold objects to an injury, such as ice, an icepack, frozen vegetables, etc.[1] It was meant to reduce swelling and inflammation by vasoconstriction.[15] However, adequate blood flow is essential in allowing cells and signals from our immune system to reach injured areas. By reducing the entry of these cells and signals to the injury, healing can be delayed, or possibly inhibited.[7][16][15][17]

The current research supports the role of ice in temporary pain relief, but there is little evidence supporting the use of ice to aid in healing, or even swelling reduction.[7] Further research is needed to further understand how ice should be applied. At this time, due to the lack of evidence, there is no consensus on the ideal temperature ranges, time frames, application methods, or patient populations when using ice on a soft tissue injury.[16] Most studies use icing protocols of intermittent 10-20 minute applications, several times a day for the first few days following an injury.[7]

Compression

editCompression refers to wearing bandages, stockings, braces, or similar devices to apply pressure over a localized area to reduce swelling and stop bleeding.[1][2] The increased pressure pushes fluids into the blood vessels to drain away from the area.[7] The effects of compression on swelling reduction are temporary and gravity-dependent.[18]

Although studies have demonstrated the effects of compression on swelling, there is little evidence to support the use of compression to promote healing.[7][9] When considering the use of compression, the evidence supports the use of elastic bandages with Intermittent Pneumatic Compression (IPC) to reduce swelling and pain, while improving range of motion.[2]

Elevation

editElevation refers to keeping an injury above the level of the heart, such as propping up a leg with pillows.[1] The goal was to reduce swelling by using gravity to encourage blood return from the swollen area back to the heart.[18] The reduction in swelling could improve pain by relieving pressure from the area. The effects of elevation on swelling have been shown to be temporary, as swelling returns when the injured area is no longer elevated.[18]

However, at this time there is little evidence to support that elevation promotes healing.[2]

Current support

editDr. Gabe Mirkin has since recanted his support for the regimen.[6] In 2015 he wrote:

Coaches have used my 'RICE' guideline for decades, but now it appears that both ice and complete rest may delay healing, instead of helping. The reasoning for this lies within the natural healing process. When an injury is created the body has to go through a very specific sequence to heal said injuries. For the next step the step prior has to be completed. The first step in the sequence is inflammation. If you use ice to reduce inflammation, it is only going to slow the healing process because inflammation needs to be complete for the sequence to keep progressing.[19] In a recent study, athletes were told to exercise so intensely that they developed severe muscle damage that caused extensive muscle soreness. Although cooling delayed swelling, it did not hasten recovery from this muscle damage.

Rest may play a role immediately after an injury, but the evidence supports early mobilization to promote healing.[9] Due to the inhibitory effects of ice on mounting a proper inflammatory response, a protocol including extended applications of ice could delay the body's attempt at healing.[16][17] While it is unclear what the effects of elevation and compression are on the healing process, reduction of swelling is a transient effect and returns when the injury is returned to a lower, gravity-dependent position.[2][18]

Currently, the RICE protocol is no longer recommended and has given way to other protocols for treating soft tissue injuries. Most recently, in 2019 the mnemonic "PEACE & LOVE" was coined by Blaise Dubois. The PEACE component stands for protection, elevation, avoid anti-inflammatories, compression, and education. It guides the treatment of acute soft tissue injuries. The LOVE component stands for load, optimism, vascularization, and exercise. It guides the treatment for the sub-chronic and chronic management of soft tissue injuries.[12] There is also evidence that points towards using heat to treat acute and soft tissue injuries. Heat has the opposite effect of ice, which restricts blood flow and slows the healing process. The use of heat will open up the blood vessels in the affected area. This helps speed up the healing process as well as reduce the possibility of persistent stagnation in the affected area and reduce the risk of future re-injury.[15]

Variations

editVariations of the acronym are sometimes used to emphasize additional steps that should be taken. These include:

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Sports Medicine Advisor 2005.4: RICE: Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation for Injuries". Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j van den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM (2012). "What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?". Journal of Athletic Training. 47 (4): 435–43. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-47.4.14. PMC 3396304. PMID 22889660.

- ^ a b c d Bayer, Monika L.; Mackey, Abigail; Magnusson, S. Peter; Krogsgaard, Michael R.; Kjær, Michael (18 February 2019). "[Treatment of acute muscle injuries]". Ugeskrift for Laeger. 181 (8): V11180753. ISSN 1603-6824. PMID 30821238.

- ^ Wojciechowksi, Andrew. "Why You Shouldn't Ice An Injury – the RICE Method Myth". Correct Toes. Correct Toes. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Mirkin, G. (1981). Sports-medicine book. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316574365.

- ^ a b Mirkin, Dr Gabe (16 September 2015). "Why Ice Delays Recovery | Dr. Gabe Mirkin on Health". Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Scialoia, Domenic; Swartzendruber, Adam J. (30 October 2020). "The R.I.C.E Protocol is a MYTH: A Review and Recommendations". The Sport Journal. 24.

- ^ a b Tiemstra, Jeffrey D. (15 June 2012). "Update on acute ankle sprains". American Family Physician. 85 (12): 1170–1176. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 22962897.

- ^ a b c d e f C M, Bleakley (2012). "PRICE needs updating, should we call the POLICE?". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (4). BMJ: 220–221. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090297. PMID 21903616. S2CID 41536790. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ a b Ivins D (2006). "Acute ankle sprain: an update". American Family Physician. 74 (10): 1714–20. PMID 17137000.

- ^ a b Bleakley CM, O'Connor S, Tully MA, Rocke LG, Macauley DC, McDonough SM (2007). "The PRICE study (Protection Rest Ice Compression Elevation): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing standard versus cryokinetic ice applications in the management of acute ankle sprain [ISRCTN13903946]". BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 8: 125. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-8-125. PMC 2228299. PMID 18093299.

- ^ a b c Dubois, Blaise; Esculier, Jean-Francois (3 August 2019). "Soft-tissue injuries simply need PEACE and LOVE". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 54 (2): 72–73. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101253. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 31377722. S2CID 199438679.

- ^ Pober, JS; Sessa, WC (23 October 2014). "Inflammation and the blood microvascular system". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (1): a016345. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016345. PMC 4292166. PMID 25384307.

- ^ Wallace, Heather A.; Basehore, Brandon M.; Zito, Patrick M. (2022), "Wound Healing Phases", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262065, retrieved 5 December 2022

- ^ a b c Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D (1 January 2004). "The Use of Ice in the Treatment of Acute Soft-Tissue Injury: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (1): 251–261. doi:10.1177/0363546503260757. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 14754753. S2CID 23999521.

- ^ a b c Wang, Zi-Ru; Ni, Guo-Xin (16 June 2021). "Is it time to put traditional cold therapy in rehabilitation of soft-tissue injuries out to pasture?". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 9 (17): 4116–4122. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4116. ISSN 2307-8960. PMC 8173427. PMID 34141774.

- ^ a b Takagi, Ryo; Fujita, Naoto; Arakawa, Takamitsu; Kawada, Shigeo; Ishii, Naokata; Miki, Akinori (1 February 2011). "Influence of icing on muscle regeneration after crush injury to skeletal muscles in rats". Journal of Applied Physiology. 110 (2): 382–388. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01187.2010. ISSN 1522-1601. PMID 21164157.

- ^ a b c d Tsang, Kavin K. W.; Hertel, Jay; Denegar, Craig R. (December 2003). "Volume Decreases After Elevation and Intermittent Compression of Postacute Ankle Sprains Are Negated by Gravity-Dependent Positioning". Journal of Athletic Training. 38 (4): 320–324. ISSN 1938-162X. PMC 314391. PMID 14737214.

- ^ Thompson, Dakota. "Sports Medicine Monday: The Efficacy of Ice on Acute Injuries". MUSC Health. MUSC Health. Retrieved 22 March 2024.