Sir Peter Brian Medawar OM CH CBE FRS (/ˈmɛdəwər/; 28 February 1915 – 2 October 1987)[1] was a British biologist and writer, whose works on graft rejection and the discovery of acquired immune tolerance have been fundamental to the medical practice of tissue and organ transplants. For his scientific works, he is regarded as the "father of transplantation".[4] He is remembered for his wit both in person and in popular writings. Richard Dawkins referred to him as "the wittiest of all scientific writers";[5] Stephen Jay Gould as "the cleverest man I have ever known".[6]

Sir Peter Medawar | |

|---|---|

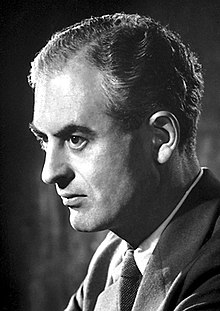

Peter Medawar, 1960 | |

| Born | Peter Brian Medawar 28 February 1915 Petrópolis, Brazil |

| Died | 2 October 1987 (aged 72) London, England |

| Citizenship | British |

| Education | Magdalen College, Oxford (BA, DSc) |

| Known for | Immunological tolerance Organ transplantation |

| Spouse | |

| Relatives | Alex Garland (grandson) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Growth promoting and growth inhibiting factors in normal and abnormal development (1941) |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students | Rupert E. Billingham (postdoc)[3] |

Medawar was the youngest child of a Lebanese father and a British mother, and was both a Brazilian and British citizen by birth. He studied at Marlborough College and Magdalen College, Oxford, and was professor of zoology at the University of Birmingham and University College London. Until he was partially disabled by a cerebral infarction, he was Director of the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill. With his doctoral student Leslie Brent and postdoctoral fellow Rupert E. Billingham, he demonstrated the principle of acquired immunological tolerance (the phenomenon of unresponsiveness of the immune system to certain molecules), which was theoretically predicted by Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet. This became the foundation of tissue and organ transplantation.[3] He and Burnet shared the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for discovery of acquired immunological tolerance".[7]

Early life and education

editMedawar was born in Petrópolis, a town 40 miles north of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where his parents were living. He was the third child of Lebanese Nicholas Agnatius Medawar, born in the village of Jounieh, north of Beirut, Lebanon, and British mother Edith Muriel (née Dowling).[8][9] He had a brother Philip and a sister Pamela. (Pamela was later married to Sir David Hunt,[10] who served as Private Secretary to prime ministers Clement Attlee and Winston Churchill.[11]) His father, a Christian Maronite, became a naturalised British citizen and worked for a British dental supplies manufacturer that sent him to Brazil as an agent.[9] (He later described his father's profession as selling "false teeth in South America".[12]) His status as a British citizen was acquired at birth, as he said, "My birth was registered at the British Consulate in good time to acquire the status of 'natural-born British subject'."[8]

Medawar left Brazil with his family for England at the end of World War I,[13] in 1918[14][15] and he lived there for the rest of his life. According to other accounts, he moved to England when he was 13 (i.e., 1928–1929)[10] or 14 (i.e., 1929–1930).[16] He was also a Brazilian citizen by birth, as dictated by the Brazilian nationality law (jus soli). At 18 years, when he was of age to be drafted in the Brazilian Army,[17] he applied for exemption of military conscription to Joaquim Pedro Salgado Filho, his godfather and the then Minister of Aviation. His application was denied by General Eurico Gaspar Dutra, and he had to renounce his Brazilian citizenship.[10][18]

In 1928, Medawar went to Marlborough College in Marlborough, Wiltshire.[9] He hated the college because "they were critical and querulous at the same time, wondering what kind of person a Lebanese was—something foreign you can be sure",[19] and also because of its preference for sports, in which he was weak.[9] An experience of bullying and racism made him feel the rest of his life "resentful and disgusted at the manners and mores of [Marlborough's] essentially tribal institution," and likened it to the training schools for the Nazi SS as all "founded upon the twin pillars of sex and sadism." His proudest moments at the college were with his teacher Ashley Gordon Lowndes, to whom he credited the beginning of his career in biology.[20] He recognised Lowndes as barely literate but "a very, very good biology teacher".[19] Lowndes had taught eminent biologists including John Z. Young and Richard Julius Pumphrey.[21] Yet Medawar was inherently weak in dissection and was constantly irked by their dictum: "Bloody foolish is the boy whose drawing of his dissection differs in any way whatsoever from the diagram in the textbook."[20]

In 1932, he went on to Magdalen College, Oxford, graduating with a first-class honours degree in zoology in 1935.[9] Medawar was appointed Christopher Welch scholar and senior demy of Magdalen in 1935. He also worked at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology supervised by Howard Florey (later Nobel laureate, and who inspired him to take up immunology) and completed his doctoral thesis in 1941.[22] In 1938, he became Fellow of Magdalen through an examination, the position he held until 1944. It was there that he started working with J. Z. Young on the regeneration of nerves. His invention of a nerve glue proved useful in surgical operations of severed nerves during the World War II.[21]

The University of Oxford approved his Doctor of Philosophy thesis titled "Growth promoting and growth inhibiting factors in normal and abnormal development" in 1941,[22] but because of the prohibitive cost of supplication (the process by which the degree is officially conferred), he spent the money on his urgent appendicectomy instead.[12] The University of Oxford later awarded him a Doctor of Science degree in 1947.[23]

Career and research

editAfter completing his PhD, Medawar was appointed a Rolleston Prizeman in 1942, senior research fellow of St John's College, Oxford, in 1944, and a university demonstrator in zoology and comparative anatomy, also in 1944.[24] He was re-elected Fellow of Magdalen from 1946 to 1947. In 1947, he became Mason Professor of Zoology at the University of Birmingham and worked there until 1951. He transferred to the University College London in 1951 as Jodrell Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy.[1]

In 1962, he was appointed director of the National Institute for Medical Research. His predecessor Sir Charles Harrington was an able administrator such that taking over his post was, as he described, "[N]o more strenuous than ... sliding over into the driving-seat of a Rolls-Royce".[25] He was head of the transplantation section of the Medical Research Council's clinical research centre at Harrow from 1971 to 1986. He became professor of experimental medicine at the Royal Institution (1977–1983), and president of the Royal Postgraduate Medical School (1981–1987).[23]

Immunology

editMedawar's first scientific research was on the effect of malt on the development of connective tissue cells (mesenchyme) in chicken. Reading the draft of the manuscript, Howard Florey commented that it was more philosophical than scientific.[24] It was published in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology in 1937.[26]

Medawar's involvement with what became transplant research began during World War II, when he investigated possible improvements in skin grafts.[22] His first publication on the subject was "Sheets of Pure Epidermal Epithelium from Human Skin", which was published in Nature in 1941.[27] His studies particularly concerned solution for skin wounds among soldiers in the war.[28][29] In 1947, he moved to the University of Birmingham, taking along with him his PhD student Leslie Brent and postdoctoral fellow Rupert Billingham. His research became more focused in 1949, when Australian biologist Frank Macfarlane Burnet, at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, advanced the hypothesis that during embryonic life and immediately after birth, cells gradually acquire the ability to distinguish between their own tissue substances on the one hand and unwanted cells and foreign material on the other.[3]

With Billingham, he published a seminal paper in 1951 on grafting technique.[30] Santa J. Ono, the American immunologist, has described the enduring impact of this paper to modern science.[31] Based on this technique of grafting, Medawar's team devised a method to test Burnet's hypothesis. They extracted cells from young mouse embryos and injected them into another mouse of different strains. When the mouse developed into adult and skin grafting from that of the original strain was performed, there was no tissue rejection. The mouse had tolerated the foreign tissue, which would normally be rejected. Their experimental proof of Burnet's hypothesis was first published in a brief article in Nature in 1953,[32] followed by a series of papers, and a comprehensive description in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B in 1956, giving the name "actively acquired tolerance".[33]

Research outcomes

editMedawar was awarded his Nobel Prize in 1960 with Burnet for their work in tissue grafting which is the basis of organ transplants, and their discovery of acquired immunological tolerance. This work was used in dealing with skin grafts required after burns. Medawar's work resulted in a shift of emphasis in the science of immunology from one that attempts to deal with the fully developed immunity mechanism to one that attempts to alter the immunity mechanism itself, as in the attempt to suppress the body's rejection of organ transplants.[34][35] It directly laid the foundation for the first successful organ transplantation in humans, specifically kidney transplantation, carried out by an American physician Joseph Murray, who eventually received the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[36]

Theory of senescence

editMedawar's 1951 lecture "An Unsolved Problem of Biology" (published 1952[37]) addressed ageing and senescence, and he begins by defining both terms as follows:

We obviously need a word for mere ageing, and I propose to use 'ageing' itself for just that purpose. 'Ageing' hereafter stands for mere ageing, and has no other innuendo. I shall use the word 'senescence' to mean ageing accompanied by that decline of bodily faculties and sensibilities and energies which ageing colloquially entails.

He then tackles the question of why evolution has permitted organisms to senesce, even though (1) senescence lowers individual fitness, and (2) there is no obvious necessity for senescence. In answering this question, Medawar provides two fundamental and interrelated insights. First, there is an inexorable decline in probability of an organism's existence, and, therefore, in what he terms "reproductive value." He suggests that it therefore follows that the force of natural selection weakens progressively with age late in life (because the fecundity of younger age-groups is overwhelmingly more significant in producing the next generation). What happens to an organism after reproduction is only weakly reflected in natural selection by the effect on its younger relatives. He pointed out that likelihood of death at various times of life, as judged by life tables, was an indirect measure of fitness, that is, the capacity of an organism to propagate its genes. Life tables for humans show, for example that the lowest likelihood of death in human females comes at about age 14, which in primitive societies would likely be an age of peak reproduction. This has served as the basis for all three modern theories for the evolution of senescence.[38][39][40]

Theory on endocrine evolution

editMedawar presented a talk on viviparity in animals (the phenomenon by which some animals give live birth) at a meeting on evolution at Oxford in July 1952.[41] Later published in 1953, he introduced an aphorism:

Endocrine evolution is not an evolution of hormones but an evolution of the uses to which they are put; an evolution not, to put it crudely, of chemical formulae but of reactivities, reaction patterns and tissue competences.[42][43]

The notion that evolution and diversity of endocrine function in animals are due to different uses of each hormone rather than different hormones themselves became an established fact.[44] The paper is also regarded as a pioneer in the field of reproductive immunology.[45]

Personal life

editMedawar never knew the exact meaning of his surname, an Arabic word, he was told, for "to make round"; but which a friend explained to him as "little round fat man".[8]

Medawar married Jean Shinglewood Taylor on 27 February 1937. They met while in graduate class at Oxford, he at Magdalen and Taylor at Somerville College. Taylor approached him for the meaning of "heuristic", which she had to ask twice, and he had to finally offer lessons in philosophy. Medawar described her as "the most beautiful woman in Oxford"; but Taylor's impression was he looked "mildly diabolical." Taylor's family objected to their marriage as Medawar had "no background, and no money." Her mother was explicitly afraid of having "black" grandchildren; her aunt disinherited her. The couple had two sons, Charles and Alexander, and two daughters, Caroline and Louise.[46]

Medawar was interested in a wide range of subjects including opera, philosophy and cricket. He was exceptionally tall, 6 ft 5 inches (196 cm), physically robust, with a big voice noted particularly during his lectures. He was renowned for wit and humour, which he claimed he inherited from his "raucous" mother. As he completed his PhD research in 1941, he did not receive the degree as he could not afford the requisite £25, to which he commented:

I'm an impostor. I am a doctor, but not a PhD... Morally I'm a PhD, in the sense I could have had one if I'd been able to afford it. Anyway it was unfashionable in my day. John Young [probably referring to John Zachary Young] was not a PhD either. A PhD was regarded then as a newfangled German importation, as bizarre and undesirable as having German bands playing on streetcorners.[8]

He was regarded as the philosopher Karl Popper's best-known disciple in science.[47]

Medawar was the maternal grandfather of the screenwriter and director Alex Garland.[48]

Views on religion

editMedawar declared:

... I believe that a reasonable case can be made for saying, not that we believe in God because He exists but rather that He exists because we believe in Him... Considered as an element of the world, God has the same degree and kind of objective reality as do other products of mind... I regret my disbelief in God and religious answers generally, for I believe it would give satisfaction and comfort to many in need of it if it were possible to discover and propound good scientific and philosophic reasons to believe in God... To abdicate from the rule of reason and substitute for it an authentication of belief by the intentness and degree of conviction with which we hold it can be perilous and destructive... I am a rationalist—something of a period piece nowadays, I admit...[49]

Although he normally sympathised with Christianity especially on moral teachings, he found the Biblical stories unethical and was "shocked by the way in which [Biblical] characters deceived and defrauded each other." He even asked his wife "to make sure that such a book did not fall into the hands of [their] children."[50]

Nonetheless, he also said the following, which suggests that although religion has good value for humans in aggregate, it does not help them all equally:

Religion has not sustained me on any of the occasions when the comfort it professes would have been most welcome.[12]

Later life and death

editIn 1959 Medawar was invited by the BBC to present the broadcaster's annual Reith Lectures—following in the footsteps of his colleague, J. Z. Young, who was Reith Lecturer in 1950. For his own series of six radio broadcasts, titled The Future of Man,[51] Medawar examined how the human race might continue to evolve.

While attending the annual British Association meeting in 1969, Medawar suffered a stroke when reading the lesson at Exeter Cathedral, a duty which falls on every new President of the British Association. It was, as he said, "monstrous bad luck because Jim Whyte Black had not yet devised beta-blockers, which slow the heart-beat and could have preserved my health and my career".[52] Medawar's failing health may have had repercussions for medical science and the relations between the scientific community and government. Before the stroke, Medawar was one of Britain's most influential scientists, especially in the biomedical field.

After the impairment of his speech and movement, Medawar, with his wife's help, reorganised his life and continued to write and do research though on a greatly restricted scale. However, more haemorrhages followed and in 1987 he died in the Royal Free Hospital, London. He is interred with his wife Jean (1913–2005) in the graveyard of St Andrew's Church in Alfriston in East Sussex.[53][54]

Awards and honours

editMedawar was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1949.[1] With Frank Macfarlane Burnet he shared the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for discovery of acquired immunological tolerance".[55] The British government conferred him a CBE in 1958, knighted him in 1965, and appointed him to the Order of the Companions of Honour in 1972, and Order of Merit in 1981. He was elected an EMBO Member in 1964[2] and received the Royal Medal in 1959, and the Copley Medal in 1969 both from the Royal Society. He was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science during 1968–1969.[23] He was awarded the UNESCO Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science in 1985.[56][57] He was awarded a Honorary Doctor of Science Degree in 1961 by the University of Birmingham.[58] He was elected a member of the American Society of Immunologists in 1971, and elected foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1959, the American Philosophical Society in 1961, and the US National Academy of Sciences in 1965.[15]

Medawar was elected President of the Royal Society for the term 1970–1975, but a severe stroke in 1969 prohibited him from taking up the office.[59]

Medawar was awarded the 1987 Michael Faraday Prize "for the contribution his books had made in presenting to the public, and to scientists themselves, the intellectual nature and the essential humanity of pursuing science at the highest level and the part it played in our modern culture".[60]

Medawar has three awards named after him:

- The Royal Society created the Medawar Lecture in 1986 in a subject relating to the history of science, philosophy of science or the social function of science.[61] Since 2007, the lecture has been merged with two older ones honouring John Wilkins and John Desmond Bernal, and became Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Lecture and the accompanying award, Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal.[62]

- Medawar Medal, awarded by the British Transplant Society in recognition of significant research in organ transplantation.[63]

- Peter Brian Medawar Medal, awarded by the State Medical Academy of Rio de Janeiro.[10]

The University of Oxford has established a research consortium named the Peter Medawar Building for Pathogen Research.[64]

The Department of Science and Technology Studies of the University College London has STS Peter Medawar Prize for undergraduate students.[65]

The University of Birmingham Public Engagement with Research (PER) Team established an annual Light of Understanding Award to individuals and groups who accomplished public engagement with research work.[66]

Publications

editMedawar was recognised as a brilliant author. Richard Dawkins called him "the wittiest of all scientific writers",[5] and New Scientist magazine's obituary called him "perhaps the best science writer of his generation".[67]

One of his best-known essays is his 1961 criticism of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's The Phenomenon of Man, of which he said: "Its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself".[68][69]

His books include

- The Uniqueness of the Individual, which includes essays on immunology, graft rejection and acquired immune tolerance. Basic Books, New York, 1957

- The Future of Man: the BBC Reith Lectures 1959, Methuen, London, 1960

- The Art of the Soluble, Methuen & Co., London/ Barnes and Noble, New York, 1967

- Induction and Intuition in Scientific Thought, American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia/Methuen & Co., London, 1969

- The Life Science, Harper & Row, 1978

- Advice to a Young Scientist, Harper & Row, 1979

- Pluto's Republic, incorporating an earlier book The Art of the Soluble, Oxford University Press, 1982

- Aristotle to Zoos (with his wife Jean Shinglewood Taylor), Harvard University Press, 1983

- The Limits of Science, Oxford University Press, 1988

- The Hope of Progress: A Scientist looks at Problems in Philosophy, Literature and Science, Anchor Press / Doubleday, Garden City, 1973

- Memoirs of a Thinking Radish: An Autobiography, Oxford University Press, 1986

- The Threat and the Glory: Reflections on Science and Scientists (ed.: David Pyke), a posthumously collected volume of essays, HarperCollins, 1990

Apart from his books on science and philosophy, he wrote a short feature article on "Some Meistersinger Records" in the issue of The Gramophone for November 1930. The author was a P. B. Medawar. The evidence that this was indeed the future Sir Peter Medawar—then a schoolboy of 15—was discussed in "Gramophone" in 1995 ("‘Gramophone’, Die Meistersinger and immunology", by John E. Havard, December 1995).

References

edit- ^ a b c d Mitchison, N. A. (1990). "Peter Brian Medawar. 28 February 1915 – 2 October 1987". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 35: 283–301. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1990.0013. PMID 11622280.

- ^ a b Anon (2016). "Peter Medawar EMBO profile". people.embo.org. Heidelberg: European Molecular Biology Organization.

- ^ a b c d e Simpson, E. (2015). "Medawar's legacy to cellular immunology and clinical transplantation: a commentary on Billingham, Brent and Medawar (1956) 'Quantitative studies on tissue transplantation immunity. III. Actively acquired tolerance'". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 370 (1666): 20140382 (online). doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0382. PMC 4360130. PMID 25750245.

- ^ Starzl, T. E. (1995). "Peter Brian Medawar: father of transplantation". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 180 (3): 332–36. PMC 2681237. PMID 7874344.

- ^ a b Dawkins, Richard, ed. (2008). The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-19-921680-2.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (2011). The Lying Stones of Marrakech: Penultimate Reflections in Natural History (1st Harvard University Press ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780674061675.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1960". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d Temple, Robert (12 April 1984). "Sir Peter Medawar". New Scientist (1405): 14–20. Retrieved 27 February 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Manuel, Diana E. (2002). "Medawar, Peter Brian (1915–1987)". Van Nostrand's Scientific Encyclopedia. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780471743989.vse10031. ISBN 978-0471743989.

- ^ a b c d Younes-Ibrahim, Maurício (2015). "Brazilian Nephrology pays homage to Peter Brian Medawar". Jornal Brasileiro de Nefrologia. 37 (1): 7–8. doi:10.5935/0101-2800.20150001. PMID 25923743.

- ^ "Obituary: Sir David Hunt". The Independent. 11 August 1998. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Paidagogos (1986). "Just a Human Being". The Expository Times. 97 (11): 352. doi:10.1177/001452468609701133. S2CID 170954307.

- ^ Glorfeld, Jeff (23 February 2020). "Peter Medawar solves rejection". Cosmos. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Ribatti, Domenico (1 October 2015). "Peter Brian Medawar and the discovery of acquired immunological tolerance". Immunology Letters. 167 (2): 63–66. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2015.07.004. ISSN 0165-2478. PMID 26192442.

- ^ a b "Sir Peter Brian Medawar, D.Sc. (1915–1987)". The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Mesquita, Evandro Tinoco; Marchese, Luana de Decco; Dias, Danielle Warol; Barbeito, Andressa Brasil; Gomes, Jonathan Costa; Muradas, Maria Clara Soares; Lanzieri, Pedro Gemal; Gismondi, Ronaldo Altenburg (2015). "Nobel prizes: contributions to cardiology". Arquivos Brasileiros De Cardiologia. 105 (2): 188–196. doi:10.5935/abc.20150041. ISSN 1678-4170. PMC 4559129. PMID 25945466.

- ^ "Diploma revalidation in Brazil: abandon all hope ye who need it". Leonardo M Alves's Blog. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Brazilian Nobel". www.brazzil.com. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ a b Robert K. G. Temple (12 April 1984). "Sir Peter Medawar" (PDF). New Scientist. 102 (1405): cover, 14–20.

- ^ a b Medawar, Peter (1986). Memoir of a Thinking Radish: An Autobiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 27–43. ISBN 0-19-217737-0. OCLC 12804275.

- ^ a b Anon. (18 February 1960). "Professor P. Medawar: A profile - A leader in the biological science". New Scientist. 7 (170): 404–405.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Medawar, Peter Brian (1941). Growth promoting and growth inhibiting factors in normal and abnormal development. bodleian.ox.ac.uk (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.673279. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Mitchison, Avrion (2009) [2004]. "Medawar, Sir Peter Brian (1915–1987)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40016. Retrieved 27 February 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b "Medawar, Peter Brian". encyclopedia.com. Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Brent, Leslie. "Sir Peter Medawar's years as director of NIMR: a vignette". NIMR History. National Institute for Medical Research. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Peter Medawar papers: Reprints, 1937–1950". Wellcome Library. Wellcome Trust. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Medawar, P. B. (1941). "Sheets of Pure Epidermal Epithelium from Human Skin". Nature. 148 (3765): 783. Bibcode:1941Natur.148..783M. doi:10.1038/148783a0. S2CID 4101700.

- ^ Medawar, P. B. (1944). "The behaviour and fate of skin autografts and skin homografts in rabbits: A report to the War Wounds Committee of the Medical Research Council". Journal of Anatomy. 78 (Pt 5): 176–199. PMC 1272490. PMID 17104960.

- ^ Medawar, P. B. (1945). "A second study of the behaviour and fate of skin homografts in rabbits: A Report to the War Wounds Committee of the Medical Research Council". Journal of Anatomy. 79 (Pt 4): 157–176. PMC 1272582. PMID 17104981.

- ^ Billingham, R. E.; Medawar, P. B. (1951). "The Technique of Free Skin Grafting in Mammals" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 28 (3): 385–402. doi:10.1242/jeb.28.3.385.

- ^ Ono, Santa Jeremy (2004). "The Birth of Transplantation Immunology: the Billingham--Medawar Experiments at Birmingham University and University College London" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (23): 4013–4014. doi:10.1242/jeb.01293. PMID 15498946. S2CID 33998370.

- ^ Billingham, R. E.; Brent, L.; Medawar, P. B. (1953). "'Actively acquired tolerance' of foreign cells". Nature. 172 (4379): 603–606. Bibcode:1953Natur.172..603B. doi:10.1038/172603a0. PMID 13099277. S2CID 4176204.

- ^ Billingham, R. E.; Brent, L.; Medawar, P. B. (1956). "Quantitative studies on tissue transplantation immunity. III. Actively acquired tolerance". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 239 (666): 357–414. Bibcode:1956RSPTB.239..357B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1956.0006.

- ^ Park, Hyung Wook (2010). "'The shape of the human being as a function of time': time, transplantation, and tolerance in Peter Brian Medawar's research, 1937–1956". Endeavour. 34 (3): 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2010.07.002. hdl:10220/9942. PMID 20692038.

- ^ Simpson, Elizabeth (2004). "Reminiscences of Sir Peter Medawar: I hope of antigen-specific transplantation tolerance". American Journal of Transplantation. 4 (12): 1937–1940. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00687.x. PMID 15575894. S2CID 9042584.

- ^ Barker, C. F.; Markmann, J. F. (1 April 2013). "Historical Overview of Transplantation". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 3 (4): a014977. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a014977. PMC 3684003. PMID 23545575.

- ^ Medawar, P. B. (1952). An Unsolved Problem of Biology. HK Lewis and Co.

- ^ Ljubuncic, Predrag; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2009). "The Evolutionary Theories of Aging Revisited – A Mini-Review". Gerontology. 55 (2): 205–216. doi:10.1159/000200772. PMID 19202326.

- ^ Charlesworth, Brian (2000). "Fisher, Medawar, Hamilton and the evolution of aging". Genetics. 156 (3): 927–31. doi:10.1093/genetics/156.3.927. PMC 1461325. PMID 11063673.

- ^ Promislow, Daniel E. L.; Pletcher, Scott D. (2002). "Advice to an aging scientist". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 123 (8): 841–850. doi:10.1016/S0047-6374(02)00021-0. PMID 12044932. S2CID 30949013.

- ^ Peaker, Malcolm (2016). "Medawar's dictum on endocrine evolution: a case of mistaken identity?". www.endocrinology.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Medawar, P.B. (1953). "Some immunological and endocrinological problems raised by the evolution of viviparity in vertebrates". Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology. 7: 320–338.

- ^ Venter, J; Diporzio, U; Robinson, D; Shreeve, S; Lai, J; Kerlavage, A; Fracekjr, S; Lentes, K; Fraser, C (1988). "Evolution of neurotransmitter receptor systems". Progress in Neurobiology. 30 (2–3): 105–169. doi:10.1016/0301-0082(88)90004-4. PMID 2830635. S2CID 42118786.

- ^ Renfree, Marilyn B. (1994), "Endocrinology of Pregnancy, Parturition and Lactation in Marsupials", in Lamming, G. E. (ed.), Marshall's Physiology of Reproduction, Springer Netherlands, pp. 677–766, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1286-4_7, ISBN 978-94-010-4561-2

- ^ Croy, B Anne (2014). "Reproductive Immunology Issue One: Cellular and Molecular Biology". Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 11 (5): 405–406. doi:10.1038/cmi.2014.64. PMC 4197211. PMID 25066420.

- ^ Richmond, Caroline (11 June 2005). "Lady Jean Medawar". BMJ. 330 (7504): 1392. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1392. PMC 558304.

- ^ Calver, Neil (20 December 2013). "Sir Peter Medawar: science, creativity and the popularization of Karl Popper". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 67 (4): 301–314. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2013.0022. PMC 3826194.

- ^ Bhattacharji, Alex (15 February 2018). "The Visionary Director of 'Ex Machina' Addresses the Controversy Surrounding His New Film". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Medawar, Medawar (1988). "'The question of the existence of God". 'The Limits of Science. Oxford University Press. pp. 94–98. ISBN 978-0-19-505212-1.

- ^ Medawar, Peter (1986). Memoir of a Thinking Radish: An Autobiography. Op cit. p. 18.

- ^ "Peter Medawar: The Future of Man: 1959". BBC Radio4. BBC. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ Medawar P. B. 1986. Memoirs of a thinking radish: an autobiography. Oxford. p. 153

- ^ Leslie Baruch Brent. "Jean Medawar's obituary" Independent, The (London). 12 May 2005.

- ^ Agran, Clive (6 August 2019). "A closer look at the history of Alfriston". Sussex Life. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1960". Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "List of Kalinga Prize Laureates". Kalinga Foundation Trust. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Kalinga Prize laureate". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "University of Birmingham". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Calver, Neil; Parker, Miles (20 March 2016). "The logic of scientific unity? Medawar, the Royal Society and the Rothschild controversy 1971–72". Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 70 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2015.0021. PMC 4759716. PMID 27017681.

- ^ "Royal Society Awards". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Rose, S. (1988). "Reflections on reductionism". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 13 (5): 160–162. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(88)90138-7. PMID 3255195.

- ^ "Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal and Lecture | Royal Society".

- ^ "Medawar Medal – British Transplantation Society".

- ^ "Home - Medawar". www.medawar.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ UCL (31 May 2018). "Prizes for undergraduate students". Science and Technology Studies. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Uobengage (15 April 2019). "Light of Understanding Award 2019 – and the winners are…". Think: Public Engagement with Research. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Editorial (October 1987). "Peter Medawar (obituary)". New Scientist. 116 (1581): 16.

- ^ Medawar, Peter (1996). "The Phenomenon of Man". The Strange Case of the Spotted Mice: And other classic essays on science. Oxford, UK & New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-286193-1. Retrieved 25 September 2010Originally published 1961 in Mind, 70, 99–106

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Medawar, P. B. (1961). "Critical Notice". Mind. LXX (277): 99–106. doi:10.1093/mind/LXX.277.99.

General sources

edit- Billington, W. David (October 2003). "The immunological problem of pregnancy: 50 years with the hope of progress. A tribute to Peter Medawar". J. Reprod. Immunol. 60 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/S0165-0378(03)00083-4. PMID 14568673.

- Kyle, Robert A.; Shampo, Marc A. (April 2003). "Peter Medawar—discoverer of immunologic tolerance". Mayo Clin. Proc. 78 (4): 401, 403. doi:10.4065/78.4.401. PMID 12683691.

- Charlesworth, B. (November 2000). "Fisher, Medawar, Hamilton and the evolution of aging". Genetics. 156 (3): 927–31. doi:10.1093/genetics/156.3.927. PMC 1461325. PMID 11063673.

- Raju, T. N. (June 1999). "The Nobel chronicles. 1960: Sir Frank Macfarlance Burnet (1899–1985), and Sir Peter Brian Medawar (1915–87)". Lancet. 353 (9171): 2253. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76313-3. PMID 10393027. S2CID 54363983.

- Rapaport, F. T. (1999). "Medawar Prize Lecture, 15 July 1998. The contribution of human subjects to experimental transplantation: the HLA story". Transplant. Proc. 31 (1–2): 60–66. doi:10.1016/S0041-1345(98)02092-2. PMID 10083012.

- Medawar, J. (1999). "Reminiscences of Peter Medawar". Transplant. Proc. 31 (1–2): 49. doi:10.1016/S0041-1345(98)02066-1. PMID 10083008.

- Terasaki, P. (1997). "1996 Medawar Prize Lecture". Transplant. Proc. 29 (1–2): 33–38. doi:10.1016/S0041-1345(96)00005-X. PMID 9123024.

- Starzl, T. E. (March 1995). "Peter Brian Medawar: Father of transplantation". J. Am. Coll. Surg. 180 (3): 332–36. PMC 2681237. PMID 7874344.

- Brent, L. (September 1992). "Sir Peter Brian Medawar (28 February 1915 – 2 October 1987)". Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 136 (3): 439–41. PMID 11623082.

- Hamilton, D. (April 1989). "Peter Medawar and clinical transplantation". Immunol. Lett. 21 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1016/0165-2478(89)90004-7. PMID 2656517.

- Gowans, J. L. (April 1989). "Peter Medawar: his life and work". Immunol. Lett. 21 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/0165-2478(89)90003-5. PMID 2656514.

- Taylor, R. M. R. (April 1989). "Articles based on presentations at the Sir Peter Medawar Memorial Symposium. London, 5 December and 6th, 1988". Immunol. Lett. 21 (1): 3. doi:10.1016/0165-2478(89)90002-3. PMID 2656507.

- Monaco, A P (February 1989). "The legacy of Sir Peter Medawar". Transplant. Proc. 21 (1 Pt 1): 1–4. PMID 2650059.

- Tanner, J. (1988). "Sir Peter Medawar 1915–1987". Ann. Hum. Biol. 15 (1): 89. doi:10.1080/03014468800009501. PMID 3279900.

- Billingham, R. E. (January 1988). "In memoriam. Sir Peter Medawar--February 18, 1915 – October 2, 1987". Transplantation. 45 (1): preceding 1. doi:10.1097/00007890-198801000-00001. PMID 3276037.

- Simpson, E. (January 1988). "Sir Peter Medawar 1915–1987". Immunol. Today. 9 (1): 4–6. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(88)91344-8. PMID 3076758.

- Melnick, M. (1988). "Peter Medawar--scientific meliorist". J. Craniofac. Genet. Dev. Biol. 8 (1): 1–2. PMID 3062035.

- Möller, G. (December 1987). "Sir Peter Medawar, 1915–1987". Immunol. Rev. 100 (6144): 9–10. Bibcode:1987Natur.330..112M. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.1987.tb00525.x. PMID 3326829. S2CID 29947524.

- Mitchison, N. A. (1987). "Sir Peter Medawar (1915–1987)". Nature. 330 (6144): 112. Bibcode:1987Natur.330..112M. doi:10.1038/330112a0. PMID 3313060. S2CID 4235230.

- "Peter Brian Medawar". Cell. Immunol. 62 (2): 235–42. August 1981. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(81)90319-1. PMID 7026052.

- Lawrence, H. (August 1981). "Advances in immunology: a meeting in honor of Sir Peter Medawar". Cell. Immunol. 62 (2): 233–310. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(81)90318-X. PMID 7026051.

- Guntrip, H. (September 1978). "Psychoanalysis and some scientific and philosophical critics: (Dr Eliot Slater, Sir Peter Medawar and Sir Karl Popper)". The British Journal of Medical Psychology. 51 (3): 207–24. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1978.tb02466.x. PMID 356870.

- Kenéz, J. (April 1975). "Medawar and organ transplantation". Orvosi Hetilap. 116 (16): 931–34. PMID 1090878.

- Sulek, K. (March 1969). "Nobel prize for F. M. Burnett and P. B. Medawar in 1960 for discovery of acquired immunological tolerance". Wiad. Lek. 22 (5): 505–06. PMID 4892417.

- "Sir Peter Brian Medawar". Triangle; the Sandoz Journal of Medical Science. 9 (2): 79–80. 1969. PMID 4939701.

External links

edit- The Personal Papers of Peter Medawar are available for study at the Wellcome Collection.

- Peter Medawar on Nobelprize.org