Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (EC 3.1.2.15, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase, UCH-L1) is a deubiquitinating enzyme.

| UCHL1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | UCHL1, HEL-117, NDGOA, PARK5, PGP 9.5, PGP9.5, PGP95, Uch-L1, HEL-S-53, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1, SPG79, UCHL-1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

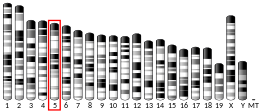

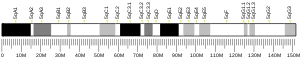

| External IDs | OMIM: 191342; MGI: 103149; HomoloGene: 37894; GeneCards: UCHL1; OMA:UCHL1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ubiquitin Carboxy-terminal Hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) | |

|---|---|

Neurons from rat brain tissue stained green with antibody to ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) which highlights the cell body strongly and the cell processes more weakly. Astrocytes are stained in red with antibody to the GFAP protein found in cytoplasmic filaments. Nuclei of all cell types are stained blue with a DNA binding dye. Antibodies, cell preparation and image generated by EnCor Biotechnology Inc. | |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy |

Function

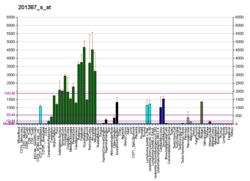

editUCH-L1 is a member of a gene family whose products hydrolyze small C-terminal adducts of ubiquitin to generate the ubiquitin monomer. Expression of UCH-L1 is highly specific to neurons and to cells of the diffuse neuroendocrine system and their tumors. It is abundantly present in all neurons (accounts for 1-2% of total brain protein), expressed specifically in neurons and testis/ovary.[5][6]

The catalytic triad of UCH-L1 contains a cysteine at position 90, an aspartate at position 176, and a histidine at position 161 that are responsible for its hydrolase activity.[7]

Relevance to neurodegenerative disorders

editA point mutation (I93M) in the gene encoding this protein is implicated as the cause of Parkinson's disease in one German family, although this finding is controversial, as no other Parkinson's disease patients with this mutation have been found.[8][9]

Furthermore, a polymorphism (S18Y) in this gene has been found to be associated with a reduced risk for Parkinson's disease.[10] This polymorphism has specifically been shown to have antioxidant activity.[11]

Another potentially protective function of UCH-L1 is its reported ability to stabilize monoubiquitin, an important component of the ubiquitin proteasome system. It is thought that by stabilizing the monomers of ubiquitin and thereby preventing their degradation, UCH-L1 increases the available pool of ubiquitin to be tagged onto proteins destined to be degraded by the proteasome.[12]

The gene is also associated with Alzheimer's disease, and required for normal synaptic and cognitive function.[13] Loss of Uchl1 increases the susceptibility of pancreatic beta-cells to programmed cell death, indicating that this protein plays a protective role in neuroendocrine cells and illustrating a link between diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases.[14]

Patients with early-onset neurodegeneration in which the causative mutation was in the UCHL1 gene (specifically, the ubiquitin binding domain, E7A) display blindness, cerebellar ataxia, nystagmus, dorsal column dysfunction, and upper motor neuron dysfunction.[15]

Ectopic expression

editAlthough UCH-L1 protein expression is specific to neurons and testis/ovary tissue, it has been found to be expressed in certain lung-tumor cell lines.[16] This abnormal expression of UCH-L1 is implicated in cancer and has led to the designation of UCH-L1 as an oncogene.[17] Furthermore there is evidence that UCH-L1 might play a role in the pathogenesis of membranous glomerulonephritis as UCH-L1 de novo expression in podocytes was seen in PHN, the rat model of human mGN.[18] This UCH-L1 expression is thought to induce at least in part podocyte hypertrophy.[19]

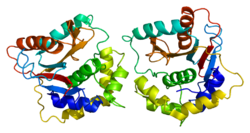

Protein structure

editHuman UCH-L1 and the closely related protein UCHL3 have one of the most complicated knot structure yet discovered for a protein, with five knot crossings. It is speculated that a knot structure may increase a protein's resistance to degradation in the proteasome.[20][21]

The conformation of the UCH-L1 protein may also be an important indication of neuroprotection or pathology. For example, the UCH-L1 dimer has been shown to exhibit the potentially pathogenic ligase activity and may lead to the aforementioned increase in aggregation of α-synuclein.[22] The S18Y polymorphism of UCH-L1 has been shown to be less-prone to dimerization.[12]

Interactions

editUbiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 has been shown to interact with COP9 constitutive photomorphogenic homolog subunit 5.[23]

UCH-L1 has also been shown to interact with α-synuclein, another protein implicated in the pathology of Parkinson disease. This activity is reported to be the result of its ubiquityl ligase activity which may be associated with the I93M pathogenic mutation in the gene.[22]

Most recently, UCH-L1 has been demonstrated to interact with the E3 ligase, parkin. Parkin has been demonstrated to bind and ubiquitinylate UCH-L1 to promote lysosomal degradation of UCH-L1.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000154277 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029223 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Doran JF, Jackson P, Kynoch PA, Thompson RJ (Jun 1983). "Isolation of PGP 9.5, a new human neurone-specific protein detected by high-resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis". Journal of Neurochemistry. 40 (6): 1542–7. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb08124.x. PMID 6343558. S2CID 24386913.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: UCHL1 ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L1 (ubiquitin thiolesterase)".

- ^ Das C, Hoang QQ, Kreinbring CA, Luchansky SJ, Meray RK, Ray SS, Lansbury PT, Ringe D, Petsko GA (Mar 2006). "Structural basis for conformational plasticity of the Parkinson's disease-associated ubiquitin hydrolase UCH-L1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (12): 4675–80. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.4675D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510403103. PMC 1450230. PMID 16537382.

- ^ Leroy E, Boyer R, Auburger G, Leube B, Ulm G, Mezey E, Harta G, Brownstein MJ, Jonnalagada S, Chernova T, Dehejia A, Lavedan C, Gasser T, Steinbach PJ, Wilkinson KD, Polymeropoulos MH (Oct 1998). "The ubiquitin pathway in Parkinson's disease". Nature. 395 (6701): 451–2. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..451L. doi:10.1038/26652. PMID 9774100. S2CID 204997455.

- ^ Harhangi BS, Farrer MJ, Lincoln S, Bonifati V, Meco G, De Michele G, Brice A, Dürr A, Martinez M, Gasser T, Bereznai B, Vaughan JR, Wood NW, Hardy J, Oostra BA, Breteler MM (Jul 1999). "The Ile93Met mutation in the ubiquitin carboxy-terminal-hydrolase-L1 gene is not observed in European cases with familial Parkinson's disease". Neuroscience Letters. 270 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00465-6. PMID 10454131. S2CID 26352360.

- ^ Wang J, Zhao CY, Si YM, Liu ZL, Chen B, Yu L (Jul 2002). "ACT and UCH-L1 polymorphisms in Parkinson's disease and age of onset". Movement Disorders. 17 (4): 767–71. doi:10.1002/mds.10179. PMID 12210873. S2CID 23026015.

- ^ Kyratzi E, Pavlaki M, Stefanis L (Jul 2008). "The S18Y polymorphic variant of UCH-L1 confers an antioxidant function to neuronal cells". Human Molecular Genetics. 17 (14): 2160–71. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn115. PMID 18411255.

- ^ a b Osaka H, Wang YL, Takada K, Takizawa S, Setsuie R, Li H, Sato Y, Nishikawa K, Sun YJ, Sakurai M, Harada T, Hara Y, Kimura I, Chiba S, Namikawa K, Kiyama H, Noda M, Aoki S, Wada K (Aug 2003). "Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 binds to and stabilizes monoubiquitin in neuron". Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (16): 1945–58. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg211. PMID 12913066.

- ^ Gong B, Cao Z, Zheng P, Vitolo OV, Liu S, Staniszewski A, Moolman D, Zhang H, Shelanski M, Arancio O (Aug 2006). "Ubiquitin hydrolase Uch-L1 rescues beta-amyloid-induced decreases in synaptic function and contextual memory". Cell. 126 (4): 775–88. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.046. PMID 16923396. S2CID 10916274.

- ^ Chu KY, Li H, Wada K, Johnson JD (Jan 2012). "Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 is required for pancreatic beta cell survival and function in lipotoxic conditions". Diabetologia. 55 (1): 128–40. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2323-1. PMID 22038515.

- ^ Bilguvar K, Tyagi NK, Ozkara C, Tuysuz B, Bakircioglu M, Choi M, Delil S, Caglayan AO, Baranoski JF, Erturk O, Yalcinkaya C, Karacorlu M, Dincer A, Johnson MH, Mane S, Chandra SS, Louvi A, Boggon TJ, Lifton RP, Horwich AL, Gunel M (Feb 2013). "Recessive loss of function of the neuronal ubiquitin hydrolase UCHL1 leads to early-onset progressive neurodegeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (9): 3489–94. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.3489B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222732110. PMC 3587195. PMID 23359680.

- ^ Liu Y, Lashuel HA, Choi S, Xing X, Case A, Ni J, Yeh LA, Cuny GD, Stein RL, Lansbury PT (Sep 2003). "Discovery of inhibitors that elucidate the role of UCH-L1 activity in the H1299 lung cancer cell line". Chemistry & Biology. 10 (9): 837–46. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.08.010. PMID 14522054.

- ^ Hussain S, Foreman O, Perkins SL, Witzig TE, Miles RR, van Deursen J, Galardy PJ (Sep 2010). "The de-ubiquitinase UCH-L1 is an oncogene that drives the development of lymphoma in vivo by deregulating PHLPP1 and Akt signaling". Leukemia. 24 (9): 1641–55. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.138. PMC 3236611. PMID 20574456.

- ^ Meyer-Schwesinger C, Meyer TN, Münster S, Klug P, Saleem M, Helmchen U, Stahl RA (Feb 2009). "A new role for the neuronal ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) in podocyte process formation and podocyte injury in human glomerulopathies". The Journal of Pathology. 217 (3): 452–64. doi:10.1002/path.2446. PMID 18985619. S2CID 23851206.

- ^ Lohmann F, Sachs M, Meyer TN, Sievert H, Lindenmeyer MT, Wiech T, Cohen CD, Balabanov S, Stahl RA, Meyer-Schwesinger C (Jul 2014). "UCH-L1 induces podocyte hypertrophy in membranous nephropathy by protein accumulation". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1842 (7): 945–58. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.02.011. PMID 24583340.

- ^ Peterson, Ivars (2006-10-14). "Knots in proteins". Science News. Archived from the original on 2008-04-21. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Virnau P, Mirny LA, Kardar M (Sep 2006). "Intricate knots in proteins: Function and evolution". PLOS Computational Biology. 2 (9): e122. Bibcode:2006PLSCB...2..122V. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020122. PMC 1570178. PMID 16978047.

- ^ a b Liu Y, Fallon L, Lashuel HA, Liu Z, Lansbury PT (Oct 2002). "The UCH-L1 gene encodes two opposing enzymatic activities that affect alpha-synuclein degradation and Parkinson's disease susceptibility". Cell. 111 (2): 209–18. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01012-7. PMID 12408865. S2CID 6849108.

- ^ Caballero OL, Resto V, Patturajan M, Meerzaman D, Guo MZ, Engles J, Yochem R, Ratovitski E, Sidransky D, Jen J (May 2002). "Interaction and colocalization of PGP9.5 with JAB1 and p27(Kip1)". Oncogene. 21 (19): 3003–10. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205390. PMID 12082530. S2CID 20004395.

- ^ McKeon JE, Sha D, Li L, Chin LS (May 2015). "Parkin-mediated K63-polyubiquitination targets ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 for degradation by the autophagy-lysosome system". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 72 (9): 1811–24. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1781-2. PMC 4395523. PMID 25403879.

Further reading

edit- Healy DG, Abou-Sleiman PM, Wood NW (Oct 2004). "Genetic causes of Parkinson's disease: UCHL-1". Cell and Tissue Research. 318 (1): 189–94. doi:10.1007/s00441-004-0917-3. PMID 15221445. S2CID 22530636.

- Rasmussen HH, van Damme J, Puype M, Gesser B, Celis JE, Vandekerckhove J (Dec 1992). "Microsequences of 145 proteins recorded in the two-dimensional gel protein database of normal human epidermal keratinocytes". Electrophoresis. 13 (12): 960–9. doi:10.1002/elps.11501301199. PMID 1286667. S2CID 41855774.

- Edwards YH, Fox MF, Povey S, Hinks LJ, Thompson RJ, Day IN (Oct 1991). "The gene for human neurone specific ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCHL1, PGP9.5) maps to chromosome 4p14". Annals of Human Genetics. 55 (Pt 4): 273–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1991.tb00853.x. PMID 1840236. S2CID 25763146.

- Honoré B, Rasmussen HH, Vandekerckhove J, Celis JE (Mar 1991). "Neuronal protein gene product 9.5 (IEF SSP 6104) is expressed in cultured human MRC-5 fibroblasts of normal origin and is strongly down-regulated in their SV40 transformed counterparts". FEBS Letters. 280 (2): 235–40. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)80300-R. PMID 1849484. S2CID 40473683.

- Day IN, Hinks LJ, Thompson RJ (Jun 1990). "The structure of the human gene encoding protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5), a neuron-specific ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase". The Biochemical Journal. 268 (2): 521–4. doi:10.1042/bj2680521. PMC 1131465. PMID 2163617.

- Day IN, Thompson RJ (Jan 1987). "Molecular cloning of cDNA coding for human PGP 9.5 protein. A novel cytoplasmic marker for neurones and neuroendocrine cells". FEBS Letters. 210 (2): 157–60. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(87)81327-3. PMID 2947814. S2CID 39218297.

- Doran JF, Jackson P, Kynoch PA, Thompson RJ (Jun 1983). "Isolation of PGP 9.5, a new human neurone-specific protein detected by high-resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis". Journal of Neurochemistry. 40 (6): 1542–7. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb08124.x. PMID 6343558. S2CID 24386913.

- Onno M, Nakamura T, Mariage-Samson R, Hillova J, Hill M (Mar 1993). "Human TRE17 oncogene is generated from a family of homologous polymorphic sequences by single-base changes". DNA and Cell Biology. 12 (2): 107–18. doi:10.1089/dna.1993.12.107. PMID 8471161.

- Larsen CN, Price JS, Wilkinson KD (May 1996). "Substrate binding and catalysis by ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases: identification of two active site residues". Biochemistry. 35 (21): 6735–44. doi:10.1021/bi960099f. PMID 8639624.

- Best CL, Pudney J, Welch WR, Burger N, Hill JA (Apr 1996). "Localization and characterization of white blood cell populations within the human ovary throughout the menstrual cycle and menopause". Human Reproduction. 11 (4): 790–7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019256. PMID 8671330.

- D'Andrea V, Malinovsky L, Berni A, Biancari F, Biassoni L, Di Matteo FM, Corbellini L, Falvo L, Santoni F, Spyrou M, De Antoni E (Oct 1997). "The immunolocalization of PGP 9.5 in normal human kidney and renal cell carcinoma". Il Giornale di Chirurgia. 18 (10): 521–4. PMID 9435142.

- Larsen CN, Krantz BA, Wilkinson KD (Mar 1998). "Substrate specificity of deubiquitinating enzymes: ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases". Biochemistry. 37 (10): 3358–68. doi:10.1021/bi972274d. PMID 9521656.

- Leroy E, Boyer R, Auburger G, Leube B, Ulm G, Mezey E, Harta G, Brownstein MJ, Jonnalagada S, Chernova T, Dehejia A, Lavedan C, Gasser T, Steinbach PJ, Wilkinson KD, Polymeropoulos MH (Oct 1998). "The ubiquitin pathway in Parkinson's disease". Nature. 395 (6701): 451–2. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..451L. doi:10.1038/26652. PMID 9774100. S2CID 204997455.

- Wada H, Kito K, Caskey LS, Yeh ET, Kamitani T (Oct 1998). "Cleavage of the C-terminus of NEDD8 by UCH-L3". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 251 (3): 688–92. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.9532. PMID 9790970.

- Leroy E, Boyer R, Polymeropoulos MH (Dec 1998). "Intron-exon structure of ubiquitin c-terminal hydrolase-L1". DNA Research. 5 (6): 397–400. doi:10.1093/dnares/5.6.397. PMID 10048490.

- Lincoln S, Vaughan J, Wood N, Baker M, Adamson J, Gwinn-Hardy K, Lynch T, Hardy J, Farrer M (Feb 1999). "Low frequency of pathogenic mutations in the ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase gene in familial Parkinson's disease". NeuroReport. 10 (2): 427–9. doi:10.1097/00001756-199902050-00040. PMID 10203348.

- Harhangi BS, Farrer MJ, Lincoln S, Bonifati V, Meco G, De Michele G, Brice A, Dürr A, Martinez M, Gasser T, Bereznai B, Vaughan JR, Wood NW, Hardy J, Oostra BA, Breteler MM (Jul 1999). "The Ile93Met mutation in the ubiquitin carboxy-terminal-hydrolase-L1 gene is not observed in European cases with familial Parkinson's disease". Neuroscience Letters. 270 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00465-6. PMID 10454131. S2CID 26352360.

- Saigoh K, Wang YL, Suh JG, Yamanishi T, Sakai Y, Kiyosawa H, Harada T, Ichihara N, Wakana S, Kikuchi T, Wada K (Sep 1999). "Intragenic deletion in the gene encoding ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase in gad mice". Nature Genetics. 23 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1038/12647. PMID 10471497. S2CID 34253163.

- Mellick GD, Silburn PA (Oct 2000). "The ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase-L1 gene S18Y polymorphism does not confer protection against idiopathic Parkinson's disease". Neuroscience Letters. 293 (2): 127–30. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01510-X. PMID 11027850. S2CID 25234210.

- Sharma N, McLean PJ, Kawamata H, Irizarry MC, Hyman BT (Oct 2001). "Alpha-synuclein has an altered conformation and shows a tight intermolecular interaction with ubiquitin in Lewy bodies". Acta Neuropathologica. 102 (4): 329–34. doi:10.1007/s004010100369. PMID 11603807. S2CID 33892290.

External links

edit- Ubiquitin+Carboxy-Terminal+Hydrolase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P09936 (Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1) at the PDBe-KB.