A planetary nebula is a type of emission nebula consisting of an expanding, glowing shell of ionized gas ejected from red giant stars late in their lives.[4]

| Planetary nebula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | Emission nebula |

| Mass range | 0.1M☉-1M☉[1] |

| Size range | ~1 ly[1] |

| Density | 100 to 10,000 particles per cm3[1] |

| External links | |

| Additional Information | |

| Discovered | 1764, Charles Messier[2] |

The term "planetary nebula" is a misnomer because they are unrelated to planets. The term originates from the planet-like round shape of these nebulae observed by astronomers through early telescopes. The first usage may have occurred during the 1780s with the English astronomer William Herschel who described these nebulae as resembling planets; however, as early as January 1779, the French astronomer Antoine Darquier de Pellepoix described in his observations of the Ring Nebula, "very dim but perfectly outlined; it is as large as Jupiter and resembles a fading planet".[5][6][7] Though the modern interpretation is different, the old term is still used.

All planetary nebulae form at the end of the life of a star of intermediate mass, about 1-8 solar masses. It is expected that the Sun will form a planetary nebula at the end of its life cycle.[8] They are relatively short-lived phenomena, lasting perhaps a few tens of millennia, compared to considerably longer phases of stellar evolution.[9] Once all of the red giant's atmosphere has been dissipated, energetic ultraviolet radiation from the exposed hot luminous core, called a planetary nebula nucleus (P.N.N.), ionizes the ejected material.[4] Absorbed ultraviolet light then energizes the shell of nebulous gas around the central star, causing it to appear as a brightly coloured planetary nebula.

Planetary nebulae probably play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of the Milky Way by expelling elements into the interstellar medium from stars where those elements were created. Planetary nebulae are observed in more distant galaxies, yielding useful information about their chemical abundances.

Starting from the 1990s, Hubble Space Telescope images revealed that many planetary nebulae have extremely complex and varied morphologies. About one-fifth are roughly spherical, but the majority are not spherically symmetric. The mechanisms that produce such a wide variety of shapes and features are not yet well understood, but binary central stars, stellar winds and magnetic fields may play a role.

Observations

editDiscovery

editThe first planetary nebula discovered (though not yet termed as such) was the Dumbbell Nebula in the constellation of Vulpecula. It was observed by Charles Messier on July 12, 1764 and listed as M27 in his catalogue of nebulous objects.[10] To early observers with low-resolution telescopes, M27 and subsequently discovered planetary nebulae resembled the giant planets like Uranus. As early as January 1779, the French astronomer Antoine Darquier de Pellepoix described in his observations of the Ring Nebula, "a very dull nebula, but perfectly outlined; as large as Jupiter and looks like a fading planet".[5][6][7]

The nature of these objects remained unclear. In 1782, William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus, found the Saturn Nebula (NGC 7009) and described it as "A curious nebula, or what else to call it I do not know". He later described these objects as seeming to be planets "of the starry kind".[11] As noted by Darquier before him, Herschel found that the disk resembled a planet but it was too faint to be one. In 1785, Herschel wrote to Jérôme Lalande:

These are celestial bodies of which as yet we have no clear idea and which are perhaps of a type quite different from those that we are familiar with in the heavens. I have already found four that have a visible diameter of between 15 and 30 seconds. These bodies appear to have a disk that is rather like a planet, that is to say, of equal brightness all over, round or somewhat oval, and about as well defined in outline as the disk of the planets, of a light strong enough to be visible with an ordinary telescope of only one foot, yet they have only the appearance of a star of about ninth magnitude.[12]

He assigned these to Class IV of his catalogue of "nebulae", eventually listing 78 "planetary nebulae", most of which are in fact galaxies.[13]

Herschel used the term "planetary nebulae" for these objects. The origin of this term not known.[10][14] The label "planetary nebula" became ingrained in the terminology used by astronomers to categorize these types of nebulae, and is still in use by astronomers today.[15][16]

Spectra

editThe nature of planetary nebulae remained unknown until the first spectroscopic observations were made in the mid-19th century. Using a prism to disperse their light, William Huggins was one of the earliest astronomers to study the optical spectra of astronomical objects.[14]

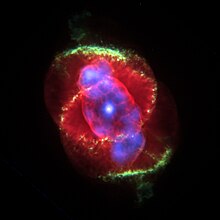

On August 29, 1864, Huggins was the first to analyze the spectrum of a planetary nebula when he observed Cat's Eye Nebula.[10] His observations of stars had shown that their spectra consisted of a continuum of radiation with many dark lines superimposed. He found that many nebulous objects such as the Andromeda Nebula (as it was then known) had spectra that were quite similar. However, when Huggins looked at the Cat's Eye Nebula, he found a very different spectrum. Rather than a strong continuum with absorption lines superimposed, the Cat's Eye Nebula and other similar objects showed a number of emission lines.[14] Brightest of these was at a wavelength of 500.7 nanometres, which did not correspond with a line of any known element.[17]

At first, it was hypothesized that the line might be due to an unknown element, which was named nebulium. A similar idea had led to the discovery of helium through analysis of the Sun's spectrum in 1868.[10] While helium was isolated on Earth soon after its discovery in the spectrum of the Sun, "nebulium" was not. In the early 20th century, Henry Norris Russell proposed that, rather than being a new element, the line at 500.7 nm was due to a familiar element in unfamiliar conditions.[10]

Physicists showed in the 1920s that in gas at extremely low densities, electrons can occupy excited metastable energy levels in atoms and ions that would otherwise be de-excited by collisions that would occur at higher densities.[18] Electron transitions from these levels in nitrogen and oxygen ions (O+, O2+ (a.k.a. O iii), and N+) give rise to the 500.7 nm emission line and others.[10] These spectral lines, which can only be seen in very low-density gases, are called forbidden lines. Spectroscopic observations thus showed that nebulae were made of extremely rarefied gas.[19]

Central stars

editThe central stars of planetary nebulae are very hot.[4] Only when a star has exhausted most of its nuclear fuel can it collapse to a small size. Planetary nebulae are understood as a final stage of stellar evolution. Spectroscopic observations show that all planetary nebulae are expanding. This led to the idea that planetary nebulae were caused by a star's outer layers being thrown into space at the end of its life.[10]

Modern observations

editTowards the end of the 20th century, technological improvements helped to further the study of planetary nebulae.[21] Space telescopes allowed astronomers to study light wavelengths outside those that the Earth's atmosphere transmits. Infrared and ultraviolet studies of planetary nebulae allowed much more accurate determinations of nebular temperatures, densities and elemental abundances.[22][23] Charge-coupled device technology allowed much fainter spectral lines to be measured accurately than had previously been possible. The Hubble Space Telescope also showed that while many nebulae appear to have simple and regular structures when observed from the ground, the very high optical resolution achievable by telescopes above the Earth's atmosphere reveals extremely complex structures.[24][25]

Under the Morgan-Keenan spectral classification scheme, planetary nebulae are classified as Type-P, although this notation is seldom used in practice.[26]

Origins

editStars greater than 8 solar masses (M⊙) will probably end their lives in dramatic supernovae explosions, while planetary nebulae seemingly only occur at the end of the lives of intermediate and low mass stars between 0.8 M⊙ to 8.0 M⊙.[27] Progenitor stars that form planetary nebulae will spend most of their lifetimes converting their hydrogen into helium in the star's core by nuclear fusion at about 15 million K. This generates energy in the core, which creates outward pressure that balances the crushing inward pressures of gravity.[28] This state of equilibrium is known as the main sequence, which can last for tens of millions to billions of years, depending on the mass.

When the hydrogen in the core starts to run out, nuclear fusion generates less energy and gravity starts compressing the core, causing a rise in temperature to about 100 million K.[29] Such high core temperatures then make[how?] the star's cooler outer layers expand to create much larger red giant stars. This end phase causes a dramatic rise in stellar luminosity, where the released energy is distributed over a much larger surface area, which in fact causes the average surface temperature to be lower. In stellar evolution terms, stars undergoing such increases in luminosity are known as asymptotic giant branch stars (AGB).[29] During this phase, the star can lose 50–70% of its total mass from its stellar wind.[30]

For the more massive asymptotic giant branch stars that form planetary nebulae, whose progenitors exceed about 0.6M⊙, their cores will continue to contract. When temperatures reach about 100 million K, the available helium nuclei fuse into carbon and oxygen, so that the star again resumes radiating energy, temporarily stopping the core's contraction. This new helium burning phase (fusion of helium nuclei) forms a growing inner core of inert carbon and oxygen. Above it is a thin helium-burning shell, surrounded in turn by a hydrogen-burning shell. However, this new phase lasts only 20,000 years or so, a very short period compared to the entire lifetime of the star.

The venting of atmosphere continues unabated into interstellar space, but when the outer surface of the exposed core reaches temperatures exceeding about 30,000 K, there are enough emitted ultraviolet photons to ionize the ejected atmosphere, causing the gas to shine as a planetary nebula.[29]

Lifetime

editAfter a star passes through the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) phase, the short planetary nebula phase of stellar evolution begins[21] as gases blow away from the central star at speeds of a few kilometers per second. The central star is the remnant of its AGB progenitor, an electron-degenerate carbon-oxygen core that has lost most of its hydrogen envelope due to mass loss on the AGB.[21] As the gases expand, the central star undergoes a two-stage evolution, first growing hotter as it continues to contract and hydrogen fusion reactions occur in the shell around the core and then slowly cooling when the hydrogen shell is exhausted through fusion and mass loss.[21] In the second phase, it radiates away its energy and fusion reactions cease, as the central star is not heavy enough to generate the core temperatures required for carbon and oxygen to fuse.[10][21] During the first phase, the central star maintains constant luminosity,[21] while at the same time it grows ever hotter, eventually reaching temperatures around 100,000 K. In the second phase, it cools so much that it does not give off enough ultraviolet radiation to ionize the increasingly distant gas cloud. The star becomes a white dwarf, and the expanding gas cloud becomes invisible to us, ending the planetary nebula phase of evolution.[21] For a typical planetary nebula, about 10,000 years[21] passes between its formation and recombination of the resulting plasma.[10]

Role in galactic enrichment

editPlanetary nebulae may play a very important role in galactic evolution. Newly born stars consist almost entirely of hydrogen and helium,[33] but as stars evolve through the asymptotic giant branch phase,[34] they create heavier elements via nuclear fusion which are eventually expelled by strong stellar winds.[35] Planetary nebulae usually contain larger proportions of elements such as carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, and these are recycled into the interstellar medium via these powerful winds. In this way, planetary nebulae greatly enrich the Milky Way and their nebulae with these heavier elements – collectively known by astronomers as metals and specifically referred to by the metallicity parameter Z.[36]

Subsequent generations of stars formed from such nebulae also tend to have higher metallicities. Although these metals are present in stars in relatively tiny amounts, they have marked effects on stellar evolution and fusion reactions. When stars formed earlier in the universe they theoretically contained smaller quantities of heavier elements.[37] Known examples are the metal poor Population II stars. (See Stellar population.)[38][39] Identification of stellar metallicity content is found by spectroscopy.

Characteristics

editPhysical characteristics

editA typical planetary nebula is roughly one light year across, and consists of extremely rarefied gas, with a density generally from 100 to 10,000 particles per cm3.[40] (The Earth's atmosphere, by comparison, contains 2.5×1019 particles per cm3.) Young planetary nebulae have the highest densities, sometimes as high as 106 particles per cm3. As nebulae age, their expansion causes their density to decrease. The masses of planetary nebulae range from 0.1 to 1 solar masses.[40]

Radiation from the central star heats the gases to temperatures of about 10,000 K.[41] The gas temperature in central regions is usually much higher than at the periphery reaching 16,000–25,000 K.[42] The volume in the vicinity of the central star is often filled with a very hot (coronal) gas having the temperature of about 1,000,000 K. This gas originates from the surface of the central star in the form of the fast stellar wind.[43]

Nebulae may be described as matter bounded or radiation bounded. In the former case, there is not enough matter in the nebula to absorb all the UV photons emitted by the star, and the visible nebula is fully ionized. In the latter case, there are not enough UV photons being emitted by the central star to ionize all the surrounding gas, and an ionization front propagates outward into the circumstellar envelope of neutral atoms.[44]

Numbers and distribution

editAbout 3000 planetary nebulae are now known to exist in our galaxy,[45] out of 200 billion stars. Their very short lifetime compared to total stellar lifetime accounts for their rarity. They are found mostly near the plane of the Milky Way, with the greatest concentration near the Galactic Center.[46]

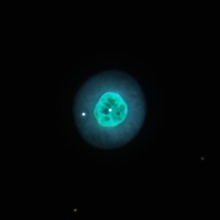

Morphology

editOnly about 20% of planetary nebulae are spherically symmetric (for example, see Abell 39).[47] A wide variety of shapes exist with some very complex forms seen. Planetary nebulae are classified by different authors into: stellar, disk, ring, irregular, helical, bipolar, quadrupolar,[48] and other types,[49] although the majority of them belong to just three types: spherical, elliptical and bipolar. Bipolar nebulae are concentrated in the galactic plane, probably produced by relatively young massive progenitor stars; and bipolars in the galactic bulge appear to prefer orienting their orbital axes parallel to the galactic plane.[50] On the other hand, spherical nebulae are probably produced by old stars similar to the Sun.[1]

The huge variety of the shapes is partially the projection effect—the same nebula when viewed under different angles will appear different.[51] Nevertheless, the reason for the huge variety of physical shapes is not fully understood.[49] Gravitational interactions with companion stars if the central stars are binary stars may be one cause. Another possibility is that planets disrupt the flow of material away from the star as the nebula forms. It has been determined that the more massive stars produce more irregularly shaped nebulae.[52] In January 2005, astronomers announced the first detection of magnetic fields around the central stars of two planetary nebulae, and hypothesized that the fields might be partly or wholly responsible for their remarkable shapes.[53][54]

Membership in clusters

editPlanetary nebulae have been detected as members in four Galactic globular clusters: Messier 15, Messier 22, NGC 6441 and Palomar 6. Evidence also points to the potential discovery of planetary nebulae in globular clusters in the galaxy M31.[55] However, there is currently only one case of a planetary nebula discovered in an open cluster that is agreed upon by independent researchers.[56][57][58] That case pertains to the planetary nebula PHR 1315-6555 and the open cluster Andrews-Lindsay 1. Indeed, through cluster membership, PHR 1315-6555 possesses among the most precise distances established for a planetary nebula (i.e., a 4% distance solution). The cases of NGC 2818 and NGC 2348 in Messier 46, exhibit mismatched velocities between the planetary nebulae and the clusters, which indicates they are line-of-sight coincidences.[46][59][60] A subsample of tentative cases that may potentially be cluster/PN pairs includes Abell 8 and Bica 6,[61][62] and He 2-86 and NGC 4463.[63]

Theoretical models predict that planetary nebulae can form from main-sequence stars of between one and eight solar masses, which puts the progenitor star's age at greater than 40 million years. Although there are a few hundred known open clusters within that age range, a variety of reasons limit the chances of finding a planetary nebula within.[46] For one reason, the planetary nebula phase for more massive stars is on the order of millennia, which is a blink of the eye in astronomic terms. Also, partly because of their small total mass, open clusters have relatively poor gravitational cohesion and tend to disperse after a relatively short time, typically from 100 to 600 million years.[64]

Current issues in planetary nebula studies

editThe distances to planetary nebulae are generally poorly determined,[65] but the Gaia mission is now measuring direct parallactic distances between their central stars and neighboring stars.[66] It is also possible to determine distances to nearby planetary nebula by measuring their expansion rates. High resolution observations taken several years apart will show the expansion of the nebula perpendicular to the line of sight, while spectroscopic observations of the Doppler shift will reveal the velocity of expansion in the line of sight. Comparing the angular expansion with the derived velocity of expansion will reveal the distance to the nebula.[24]

The issue of how such a diverse range of nebular shapes can be produced is a debatable topic. It is theorised that interactions between material moving away from the star at different speeds gives rise to most observed shapes.[49] However, some astronomers postulate that close binary central stars might be responsible for the more complex and extreme planetary nebulae.[67] Several have been shown to exhibit strong magnetic fields,[68] and their interactions with ionized gas could explain some planetary nebulae shapes.[54]

There are two main methods of determining metal abundances in nebulae. These rely on recombination lines and collisionally excited lines. Large discrepancies are sometimes seen between the results derived from the two methods. This may be explained by the presence of small temperature fluctuations within planetary nebulae. The discrepancies may be too large to be caused by temperature effects, and some hypothesize the existence of cold knots containing very little hydrogen to explain the observations. However, such knots have yet to be observed.[69]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d Osterbrock, Donald E.; Ferland, G. J. (2005), Ferland, G. J. (ed.), Astrophysics of gaseous nebulae and active galactic nuclei, University Science Books, ISBN 978-1-891389-34-4

- ^ "Messier 27 (The Dumbbell Nebula)". nasa.gov. 19 Oct 2017.

- ^ Miszalski et al. 2011

- ^ a b c Frankowski & Soker 2009, pp. 654–8

- ^ a b Darquier, A. (1777). Observations astronomiques, faites à Toulouse (Astronomical observations, made in Toulouse). Avignon: J. Aubert; (and Paris: Laporte, etc.).

- ^ a b Olson, Don; Caglieris, Giovanni Maria (June 2017). "Who Discovered the Ring Nebula?". Sky & Telescope. pp. 32–37.

- ^ a b Wolfgang Steinicke. "Antoine Darquier de Pellepoix". Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ Daley, Jason (May 8, 2018). "The Sun Will Produce a Beautiful Planetary Nebula When It Dies". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ They are created after the red giant phase, when most of the outer layers of the star have been expelled by strong stellar winds Frew & Parker 2010, pp. 129–148

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kwok 2000, pp. 1–7

- ^ Zijlstra, A. (2015). "Planetary nebulae in 2014: A review of research" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. 51: 221–230. arXiv:1506.05508. Bibcode:2015RMxAA..51..221Z. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Quoted in Hoskin, Michael (2014). "William Herschel and the Planetary Nebulae". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 45 (2): 209–225. Bibcode:2014JHA....45..209H. doi:10.1177/002182861404500205. S2CID 122897343.

- ^ p. 16 in Mullaney, James (2007). The Herschel Objects and How to Observe Them. Astronomers' Observing Guides. Bibcode:2007hoho.book.....M. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-68125-2. ISBN 978-0-387-68124-5.

- ^ a b c Moore 2007, pp. 279–80

- ^ SEDS 2013

- ^ Hubblesite.org 1997

- ^ Huggins & Miller 1864, pp. 437–44

- ^ Bowen 1927, pp. 295–7

- ^ Gurzadyan 1997

- ^ "A Planetary Nebula Divided". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kwok 2005, pp. 271–8

- ^ Hora et al. 2004, pp. 296–301

- ^ Kwok et al. 2006, pp. 445–6

- ^ a b Reed et al. 1999, pp. 2430–41

- ^ Aller & Hyung 2003, p. 15

- ^ Krause 1961, p. 187

- ^ Maciel, Costa & Idiart 2009, pp. 127–37

- ^ Harpaz 1994, pp. 55–80

- ^ a b c Harpaz 1994, pp. 99–112

- ^ Wood, P. R.; Olivier, E. A.; Kawaler, S. D. (2004). "Long Secondary Periods in Pulsating Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars: An Investigation of Their Origin". The Astrophysical Journal. 604 (2): 800. Bibcode:2004ApJ...604..800W. doi:10.1086/382123. S2CID 121264287.

- ^ "Hubble Offers a Dazzling Necklace". Picture of the Week. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ "An Interstellar Distributor". Picture of the Week. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ W. Sutherland (26 March 2013). "The Galaxy. Chapter 4. Galactic Chemical Evolution" (PDF). Retrieved 13 January 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sackmann, I. -J.; Boothroyd, A. I.; Kraemer, K. E. (1993). "Our Sun. III. Present and Future". The Astrophysical Journal. 418: 457. Bibcode:1993ApJ...418..457S. doi:10.1086/173407.

- ^ Castor, J.; McCray, R.; Weaver, R. (1975). "Interstellar Bubbles". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 200: L107–L110. Bibcode:1975ApJ...200L.107C. doi:10.1086/181908.

- ^ Kwok 2000, pp. 199–207

- ^ Pan, Liubin; Scannapieco, Evan; Scalo, Jon (1 October 2013). "Modeling the Pollution of Pristine Gas in the Early Universe". The Astrophysical Journal. 775 (2): 111. arXiv:1306.4663. Bibcode:2013ApJ...775..111P. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/775/2/111. S2CID 119233184.

- ^ Marochnik, Shukurov & Yastrzhembsky 1996, pp. 6–10

- ^ Zeilik, Michael; Gregory, Stephen A. (1998). Introductory astronomy & astrophysics (4. ed.). Fort Worth [u.a.]: Saunders College Publishing. p. 322. ISBN 0-03-006228-4.

- ^ a b Osterbrock & Ferland 2005, p. 10

- ^ Gurzadyan 1997, p. 238

- ^ Gurzadyan 1997, pp. 130–7

- ^ Osterbrock & Ferland 2005, pp. 261–2

- ^ Osterbrock & Ferland 2005, p. 207

- ^ Parker et al. 2006, pp. 79–94

- ^ a b c Majaess, Turner & Lane 2007, pp. 1349–60

- ^ Jacoby, Ferland & Korista 2001, pp. 272–86

- ^ Kwok & Su 2005, pp. L49–52

- ^ a b c Kwok 2000, pp. 89–96

- ^ Rees & Zijlstra 2013

- ^ Chen, Z; A. Frank; E. G. Blackman; J. Nordhaus; J. Carroll-Nellenback (2017). "Mass Transfer and Disc Formation in AGB Binary Systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 468 (4): 4465. arXiv:1702.06160. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.468.4465C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx680. S2CID 119073723.

- ^ Morris 1990, pp. 526–30

- ^ SpaceDaily Express 2005

- ^ a b Jordan, Werner & O'Toole 2005, pp. 273–9

- ^ Jacoby, George H.; Ciardullo, Robin; De Marco, Orsola; Lee, Myung Gyoon; Herrmann, Kimberly A.; Hwang, Ho Seong; Kaplan, Evan; Davies, James E., (2013). A Survey for Planetary Nebulae in M31 Globular Clusters, ApJ, 769, 1

- ^ Frew, David J. (2008). Planetary Nebulae in the Solar Neighbourhood: Statistics, Distance Scale and Luminosity Function, PhD Thesis, Department of Physics, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

- ^ Parker 2011, pp. 1835–1844

- ^ Majaess, D.; Carraro, G.; Moni Bidin, C.; Bonatto, C.; Turner, D.; Moyano, M.; Berdnikov, L.; Giorgi, E., (2014). On the crucial cluster Andrews-Lindsay 1 and a 4% distance solution for its planetary nebula, A&A, 567

- ^ Kiss et al. 2008, pp. 399–404

- ^ Mermilliod et al. 2001, pp. 30–9

- ^ Bonatto, C.; Bica, E.; Santos, J. F. C., (2008). Discovery of an open cluster with a possible physical association with a planetary nebula, MNRAS, 386, 1

- ^ Turner, D. G.; Rosvick, J. M.; Balam, D. D.; Henden, A. A.; Majaess, D. J.; Lane, D. J. (2011). New Results for the Open Cluster Bica 6 and Its Associated Planetary Nebula Abell 8, PASP, 123, 909

- ^ Moni Bidin, C.; Majaess, D.; Bonatto, C.; Mauro, F.; Turner, D.; Geisler, D.; Chené, A.-N.; Gormaz-Matamala, A. C.; Borissova, J.; Kurtev, R. G.; Minniti, D.; Carraro, G.; Gieren, W. (2014). Investigating potential planetary nebula/cluster pairs, A&A, 561

- ^ Allison 2006, pp. 56–8

- ^ R. Gathier. "Distances to Planetary Nebulae" (PDF). ESO Messenger. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "SIMBAD references".

- ^ Soker 2002, pp. 481–6

- ^ Gurzadyan 1997, p. 424

- ^ Liu et al. 2000, pp. 585–587

Cited sources

edit- Aller, Lawrence H.; Hyung, Siek (2003). "Historical Remarks on the Spectroscopic Analysis of Planetary Nebulae (invited review)". In Kwok, Sun; Dopita, Michael; Sutherland, Ralph (eds.). Planetary Nebulae: Their Evolution and Role in the Universe, Proceedings of the 209th Symposium of the International Astronomical Union held at Canberra, Australia, 19-23 November, 2001. Vol. 209. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. p. 15. Bibcode:2003IAUS..209...15A.

- Allison, Mark (2006), Star clusters and how to observe them, Birkhäuser, pp. 56–8, ISBN 978-1-84628-190-7

- Bowen, I. S. (October 1927), "The Origin of the Chief Nebular Lines", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 39 (231): 295–7, Bibcode:1927PASP...39..295B, doi:10.1086/123745

- Frankowski, Adam; Soker, Noam (November 2009), "Very late thermal pulses influenced by accretion in planetary nebulae", New Astronomy, 14 (8): 654–8, arXiv:0903.3364, Bibcode:2009NewA...14..654F, doi:10.1016/j.newast.2009.03.006, S2CID 17128522,

A planetary nebula (PN) is an expanding ionized circumstellar cloud that was ejected during the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) phase of the stellar progenitor.

- Frew, David J.; Parker, Quentin A. (May 2010), "Planetary Nebulae: Observational Properties, Mimics and Diagnostics", Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 27 (2): 129–148, arXiv:1002.1525, Bibcode:2010PASA...27..129F, doi:10.1071/AS09040, S2CID 59429975

- Gurzadyan, Grigor A. (1997), The Physics and dynamics of planetary nebulae, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-60965-0

- Harpaz, Amos (1994), Stellar Evolution, A K Peters, Ltd., ISBN 978-1-56881-012-6

- Hora, Joseph L.; Latter, William B.; Allen, Lori E.; Marengo, Massimo; Deutsch, Lynne K.; Pipher, Judith L. (September 2004), "Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) Observations of Planetary Nebulae" (PDF), Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 154 (1): 296–301, arXiv:astro-ph/0405614, Bibcode:2004ApJS..154..296H, doi:10.1086/422820, S2CID 53381952

- Hubble Witnesses the Final Blaze of Glory of Sun-Like Stars, Hubblesite.org - Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) for NASA, 17 December 1997, archived from the original on 12 June 2018, retrieved 10 June 2018

- Huggins, W.; Miller, W. A. (1864), "On the Spectra of some of the Nebulae", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 154: 437–44, Bibcode:1864RSPT..154..437H, doi:10.1098/rstl.1864.0013

- Jacoby, George. H.; Ferland, Gary. J.; Korista, Kirk T. (2001), "The Planetary Nebula A39: An Observational Benchmark for Numerical Modeling of Photoionized Plasmas", The Astrophysical Journal, 560 (1): 272–86, Bibcode:2001ApJ...560..272J, doi:10.1086/322489

- Jordan, S.; Werner, K.; O'Toole, S. J. (March 2005), "Discovery of magnetic fields in central stars of planetary nebulae", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 432 (1): 273–9, arXiv:astro-ph/0501040, Bibcode:2005A&A...432..273J, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041993, S2CID 119361869

- Kiss, L. L.; Szabó, Gy. M.; Balog, Z.; Parker, Q. A.; Frew, D. J. (November 2008), "AAOmega radial velocities rule out current membership of the planetary nebula NGC 2438 in the open cluster M46", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 391 (1): 399–404, arXiv:0809.0327, Bibcode:2008MNRAS.391..399K, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13899.x, S2CID 15207860

- Krause, Arthur (1961), Astronomy, Oliver and Boyd, p. 187

- Kwok, Sun (2000), The origin and evolution of planetary nebulae, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62313-8, archived from the original on March 2, 2012 (Chapter 1 can be downloaded here.)

- Kwok, Sun (June 2005), "Planetary Nebulae: New Challenges in the 21st Century", Journal of the Korean Astronomical Society, 38 (2): 271–8, Bibcode:2005JKAS...38..271K, doi:10.5303/JKAS.2005.38.2.271

- Kwok, Sun; Su, Kate Y. L. (December 2005), "Discovery of Multiple Coaxial Rings in the Quadrupolar Planetary Nebula NGC 6881", The Astrophysical Journal, 635 (1): L49–52, Bibcode:2005ApJ...635L..49K, doi:10.1086/499332,

We report the discovery of multiple two-dimensional rings in the quadrupolar planetary nebula NGC 6881. As many as four pairs of rings are seen in the bipolar lobes, and three rings are seen in the central torus. While the rings in the lobes have the same axis as one pair of the bipolar lobes, the inner rings are aligned with the other pair. The two pairs of bipolar lobes are likely to be carved out by two separate high-velocity outflows from the circumstellar material left over from the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) wind. The two-dimensional rings could be the results of dynamical instabilities or the consequence of a fast outflow interacting with remnants of discrete AGB circumstellar shells.

- Kwok, Sun; Koning, Nico; Huang, Hsiu-Hui; Churchwell, Edward (2006), Barlow, M. J.; Méndez, R. H. (eds.), "Planetary nebulae in the GLIMPSE survey", Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, Planetary Nebulae in our Galaxy and Beyond, 2 (S234), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 445–6, Bibcode:2006IAUS..234..445K, doi:10.1017/S1743921306003668 (inactive 1 November 2024),

Planetary nebulae (PNs) have high dust content and radiate strongly in the infrared. For young PNs, the dust component accounts for about one third of the total energy output of the nebulae (Zhang & Kwok 1991). The typical color temperatures of PNs are between 100 and 200 K, and at λ >5 μm, dust begins to dominate over bound-free emission from the ionized component. Although PNs are traditionally discovered through examination of photographic plates or Hα surveys, PNs can also be identified in infrared surveys by searching for red objects with a rising spectrum between 4–10 μm.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Liu, X.-W.; Storey, P. J.; Barlow, M. J.; Danziger, I. J.; Cohen, M.; Bryce, M. (March 2000), "NGC 6153: a super–metal–rich planetary nebula?", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 312 (3): 585–628, Bibcode:2000MNRAS.312..585L, doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2000.03167.x

- Maciel, W. J.; Costa, R. D. D.; Idiart, T. E. P. (October 2009), "Planetary nebulae and the chemical evolution of the Magellanic Clouds", Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, 45: 127–37, arXiv:0904.2549, Bibcode:2009RMxAA..45..127M,

These objects are produced by low and intermediate mass stars, with main sequence masses roughly between 0.8 and 8 M⊙, and present a reasonably large age and metallicity spread.

- Majaess, D. J.; Turner, D.; Lane, D. (December 2007), "In Search of Possible Associations between Planetary Nebulae and Open Clusters", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 119 (862): 1349–60, arXiv:0710.2900, Bibcode:2007PASP..119.1349M, doi:10.1086/524414, S2CID 18640979

- Marochnik, L.S.; Shukurov, Anwar; Yastrzhembsky, Igor (1996), "Chapter 19: Chemical abundances", The Milky Way galaxy, Taylor & Francis, pp. 6–10, ISBN 978-2-88124-931-0

- Mermilliod, J.-C.; Clariá, J. J.; Andersen, J.; Piatti, A. E.; Mayor, M. (August 2001), "Red giants in open clusters. IX. NGC 2324, 2818, 3960 and 6259", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 375 (1): 30–9, Bibcode:2001A&A...375...30M, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.30.7545, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010845, S2CID 122773065

- Miszalski, B.; Jones, D.; Rodríguez-Gil, P.; Boffin, H. M. J.; Corradi, R. L. M.; Santander-García, M. (2011), "Discovery of close binary central stars in the planetary nebulae NGC 6326 and NGC 6778", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 531: A158, arXiv:1105.5731, Bibcode:2011A&A...531A.158M, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117084, S2CID 15010950

- Moore, S. L. (October 2007), "Observing the Cat's Eye Nebula", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 117 (5): 279–80, Bibcode:2007JBAA..117R.279M

- Morris, M. (1990), "Bipolar asymmetry in the mass outflows of stars in transition", in Mennessier, M.O.; Omont, Alain (eds.), From Miras to planetary nebulae: which path for stellar evolution?, Montpellier, France, September 4–7, 1989 IAP astrophysics meeting: Atlantica Séguier Frontières, pp. 526–30, ISBN 978-2-86332-077-8

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Osterbrock, Donald E.; Ferland, G. J. (2005), Ferland, G. J. (ed.), Astrophysics of gaseous nebulae and active galactic nuclei, University Science Books, ISBN 978-1-891389-34-4

- Parker, Quentin A.; Acker, A.; Frew, D. J.; Hartley, M.; Peyaud, A. E. J.; Ochsenbein, F.; Phillipps, S.; Russeil, D.; Beaulieu, S. F.; Cohen, M.; Köppen, J.; Miszalski, B.; Morgan, D. H.; Morris, R. A. H.; Pierce, M. J.; Vaughan, A. E. (November 2006), "The Macquarie/AAO/Strasbourg Hα Planetary Nebula Catalogue: MASH", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 373 (1): 79–94, Bibcode:2006MNRAS.373...79P, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10950.x

- Parker, Quentin A.; Frew, David J.; Miszalski, B.; Kovacevic, Anna V.; Frinchaboy, Peter.; Dobbie, Paul D.; Köppen, J. (May 2011), "PHR 1315–6555: A bipolar planetary nebula in the compact Hyades-age open cluster ESO 96-SC04", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 413 (3): 1835–1844, arXiv:1101.3814, Bibcode:2011MNRAS.413.1835P, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18259.x, S2CID 16164749

- Reed, Darren S.; Balick, Bruce; Hajian, Arsen R.; Klayton, Tracy L.; Giovanardi, Stefano; Casertano, Stefano; Panagia, Nino; Terzian, Yervant (November 1999), "Hubble Space Telescope Measurements of the Expansion of NGC 6543: Parallax Distance and Nebular Evolution", Astronomical Journal, 118 (5): 2430–41, arXiv:astro-ph/9907313, Bibcode:1999AJ....118.2430R, doi:10.1086/301091, S2CID 14746840

- Soker, Noam (February 2002), "Why every bipolar planetary nebula is 'unique'", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 330 (2): 481–6, arXiv:astro-ph/0107554, Bibcode:2002MNRAS.330..481S, doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05105.x, S2CID 16616082

- The first detection of magnetic fields in the central stars of four planetary nebulae, SpaceDaily Express, January 6, 2005, retrieved October 18, 2009,

Source: Journal Astronomy & Astrophysics

- Rees, B.; Zijlstra, A.A. (July 2013), "Alignment of the Angular Momentum Vectors of Planetary Nebulae in the Galactic Bulge", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 435 (2): 975–991, arXiv:1307.5711, Bibcode:2013MNRAS.435..975R, doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1300, S2CID 118414177

- Planetary Nebulae, SEDS, September 9, 2013, retrieved 2013-11-10

Further reading

edit- Iliadis, Christian (2007), Nuclear physics of stars. Physics textbook, Wiley-VCH, pp. 18, 439–42, ISBN 978-3-527-40602-9

- Renzini, A. (1987), S. Torres-Peimbert (ed.), "Thermal pulses and the formation of planetary nebula shells", Proceedings of the 131st Symposium of the IAU, 131: 391–400, Bibcode:1989IAUS..131..391R

External links

edit- Entry in the Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight

- Press release on recent observations of the Cat's Eye Nebula

- Planetary Nebulae, SEDS Messier Pages

- The first detection of magnetic fields in the central stars of four planetary nebulae

- Planetary Nebulae—Information and amateur observations

- Planetary nebula on arxiv.org