The Brighton Palace Pier, commonly known as Brighton Pier or the Palace Pier,[a] is a Grade II* listed pleasure pier in Brighton, England, located in the city centre opposite the Old Steine. Established in 1899, it was the third pier to be constructed in Brighton after the Royal Suspension Chain Pier and the West Pier, but is now the only one still in operation. It is managed and operated by the Eclectic Bar Group.

Brighton Palace Pier in October 2011 | |

| Type | Pleasure Pier |

|---|---|

| Official name | Brighton Palace Pier |

| Owner | Eclectic Bar Group |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 1,722 feet (525 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | R. St George Moore |

| Opening date | 20 May 1899 |

| Coordinates | 50°48′54″N 0°08′13″W / 50.81500°N 0.13694°W |

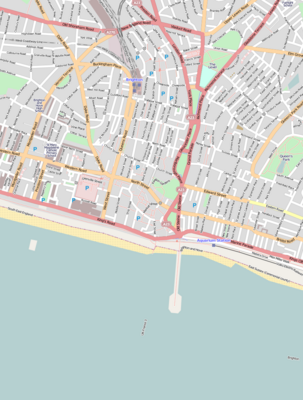

Location of pier in Brighton

www | |

The Palace Pier was intended as a replacement for the Chain Pier, which collapsed in 1896 during construction of the new pier. It quickly became popular, and had become a frequently-visited theatre and entertainment venue by 1911. Aside from closures owing to war, it continued to hold regular entertainment up to the 1970s. The theatre was damaged in 1973 and following a buy-out was demolished in 1986, changing the pier's character from seaside entertainment to an amusement park, with various fairground rides and roller coasters.

The pier remains popular with the public, with over four million visitors in 2016, and has been featured in many works of British culture, including the gangster thriller Brighton Rock, the comedy Carry On at Your Convenience and the Who's concept album and film Quadrophenia.

Location

editThe pier entrance is opposite the southern end of Old Steine (the A23 to London) where it meets Marine Parade and Grand Junction Road which run along the seafront.[2] It is 1,722 feet (525 m) long[3] and contains 85 miles (137 km) of planking.[4] Because of the pier's length, repainting it takes three months every year. At night, it is illuminated by 67,000 bulbs.[5]

No. 14 and No. 27 buses run directly from Brighton railway station to the pier.[6]

History

edit1891–1970

edit| Brighton Marine Palace and Pier Act 1899 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Long title | An Act to extend the period limited for the construction and completion of the Brighton Marine Palace and Pier and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 62 & 63 Vict. c. clxi |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 1 August 1899 |

The pier was designed and constructed by R. St George Moore.[7] It was the third in Brighton, following the Royal Suspension Chain Pier in 1823 and the West Pier in 1866. The inaugural ceremony for laying of the first pile was held on 7 November 1891, overseen by Mayor Samuel Henry Soper.[8] A condition to be met by its builders, in exchange for permission to build, was that the Chain Pier was to be demolished as it had fallen into a state of disrepair.[9] In 1896, a storm destroyed the remains of the Chain Pier, which narrowly avoided colliding with the new pier during its collapse. Some of its remaining parts, including the toll houses, were re-used for the new pier.[10] A tram along the pier was in operation during construction, but it was dismantled two years after opening.[7]

Work was mostly completed in 1899 and the pier was officially opened on 20 May by the Mayoress of Brighton.[11] It was named the Brighton Marine Palace and Pier, whose name was inscribed into the pier's metalwork.[10][12] It cost a record £27,000 (£3,839,000 in 2023) to build,[13] including 3,000 lights to illuminate the pier. Part of the cost was repairs to the West Pier and the nearby Volk's Electric Railway caused by damage in the 1896 storm from the Chain Pier's debris.[10] The pier was not fully complete on the opening date; some work on the pavilion was completed shortly afterwards. It was designed to resemble kursaals, which were entertainment buildings found near spas on the Continent, and included reading and dining rooms.[11][14]

The pier was an immediate success and quickly became one of the most popular landmarks in Brighton.[10] By 1911, the reading rooms had been converted into a theatre.[9] Both Stan Laurel and Charlie Chaplin performed at the pier to hone their comic skills early in their career, before migrating to the US and finding major commercial success in Hollywood. During World War I, the sea surrounding the pier was extensively mined to prevent enemy attacks.[10] In the 1920s, the pier was widened, and a distinctive clock tower was added.[9]

During World War II, the pier was closed as a security precaution. A section of decking was removed in order to prevent access from an enemy landing.[9] The pier regained its popularity after the war, and continued to run regular summer shows, including Tommy Trinder, Doris and Elsie Waters and Dick Emery.[9]

1970–2000

editThe pier was listed at Grade II* on 20 August 1971.[15] As of February 2001, it was one of 70 Grade II*-listed buildings and structures, and 1,218 listed buildings of all grades, in the city of Brighton and Hove.[16]

During a storm in 1973, a 70-long-ton (71 t) barge moored at the pier's landing stage broke loose and began to damage the pier head, particularly the theatre.[9] Despite fears that the pier would be destroyed, the storm eased and the barge was removed.[9] The landing pier was demolished in 1975, and the damaged theatre was never used again, despite protests from the Theatres Trust.[7][9]

The pier was sold to the Noble Organisation in 1984. The theatre was removed two years later, on the understanding that it would be replaced; however a domed amusement arcade was put in place instead.[9] Consequently, the seaward end of the pier was filled with fairground rides, including thrill rides, children's rides and roller coasters.[17] Entertainment continued to be popular at the pier; the Spice Girls made an early live performance there in 1996 and returned the following year after achieving commercial success.[9]

On 13 August 1994, a bomb planted by the IRA near the pier was defused by a controlled explosion. A similar bomb by the same perpetrators had exploded in Bognor Regis on the same day. The bombing was intended to mark the 25th anniversary of the start of The Troubles. The pier was closed for several days owing to police investigation.[18][19]

2000–present

editThe pier was renamed as "Brighton Pier" in 2000, although this legal change was not recognised by the National Piers Society nor some residents of Brighton and Hove.[20] The local newspaper, The Argus, continued to refer to the structure as the Palace Pier.[1]

The Palace Pier caught fire on the evening of 4 February 2003, most of it reopening the following day with police suspecting arson.[21] The fire destroyed the ghost train ride, which is where the fire started, as well as damaging two other rides and leaving a hole in the pier's decking, but luckily not causing any structural damage.[22][23]

In 2004, the Brighton Marine Palace Pier Company (owned by the Noble Organisation), admitted an offence of breaching public safety under the Health and Safety at Work Act and had to pay fines and costs of £37,000 after a fairground ride was operated with part of its track missing. A representative from the Health and Safety Executive said that inadequate procedures were to blame for the fact that nothing had been done to alert staff or passengers that the ride would be dangerous to use.[24] The pier management came into criticism from Brighton and Hove City Council, who thought they were relying too much on fairground rides, some of which were being built too high.[9]

In 2011, the Noble Organisation put the pier for sale, with an expected price of £30 million. It was rumoured that the council wanted to buy the pier, but this was quickly ruled out. It was taken off the market the following year, due to lack of interest in suitable buyers.[7] In 2016, it was sold to the Eclectic Bar Group, headed by former PizzaExpress owner Luke Johnson, who renamed the pier back to Brighton Palace Pier in July.[7]

The Palace Pier remains a popular tourist attraction into the 21st century, particularly with day visitors to the city. In contrast to the redevelopment and liberal culture in Brighton generally, it has retained a traditional down-market "bucket and spade" seaside atmosphere.[25] In 2016, the Brighton Fringe festival director Julian Caddy criticised the pier as "a massive public relations problem".[26]

On 8 April 2019 a piece of the Air Race ride, manufactured by Zamperla, came loose and hit some people, injuring four people, one of whom was taken to hospital.[27]

In 2024 it was announced that the pier would introduce a £1 admission fee beginning on 25 May. The fee is in place over weekends during June and throughout July and August and will not apply to local residents who have a Brighton Palace Pier local residents card.[28][29]

Rides

editThe pier includes several fairground rides, such as two roller coasters, a haunted house ride, a traditional carousel, a helter skelter and a cup and saucer ride. The Booster is a pendulum ride by Fabbri, which catapults people 130 feet (40 m) into the air, turning upside down in the process.[30][31]

For young children, Fantasia is a simple ride featuring Disney characters.[30]

Cultural references

editThe pier has featured regularly in British popular culture. It is shown prominently in the 1971 film, Carry on at Your Convenience,[25] and it is shown to represent Brighton in several film and television features, including MirrorMask, The Persuaders, the Doctor Who serial The Leisure Hive (1980), the 1986 film Mona Lisa, and the 2007 film, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.[4]

The Graham Greene novel Brighton Rock featured the Palace Pier. John Boulting's 1947 film adaptation helped established "low life" subculture in Brighton, and the climax of the film is set on it, where gangleader Pinkie Brown (played by Richard Attenborough) falls to his death.[32] The 1953 B movie Girl on a Pier is set around the Palace Pier and also features the clash between holidaymakers and gangsters in Brighton.[33] The Who's 1973 concept album Quadrophenia was inspired in part by band leader Pete Townshend spending a night underneath the pier in March 1964. It is a pivotal part of the album's plot, and features in the 1979 film. Townshend later said that the rest of the band understood this element of the story, as it related to their mod roots.[34]

The 2014 novel The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell includes passages that take place on the pier.[35] The 2015 British TV series, Cuffs, which takes place in Brighton features the pier, both in the opening theme as well as in parts of the story lines.[36] Graham Swift's 2020 novel Here We Are, focuses on a trio of entertainers performing at the pier in the immediate postwar period.[37]

In 2015, Martyn Ware, founding member of pop group the Human League, made a series of field recordings on the pier as part of a project with the National Trust and British Library project to capture the sounds of Britain.[7]

Accolades

editThe pier was awarded the National Piers Society's Pier of the Year award in 1998.[4] In 2017, it was listed as the fourth most popular free attraction in Britain in a National Express survey.[38]

In 2017, the pier was said to be the most visited tourist attraction outside London, with over 4.5 million visitors the previous year.[39]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

Citations

- ^ a b "Victory as new owners agree to put back 'Palace' to pier name". The Argus. 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Brighton Palace Pier". Google Maps. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "History". Brighton Palace Pier. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "Brighton Pier – Facts and Figures". Daily Telegraph. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "UK's Best Seaside Towns - From Brighton to Newquay". The Independent. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Getting Here". Brighton Palace Pier. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brighton Palace". National Piers Society. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Betjeman 1972, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Palace Pier celebrates 110-year anniversary". The Argus. 22 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Newman 2016, p. 34.

- ^ a b "Opening Of A New Pier At Brighton". The Times. London. 22 May 1899. p. 9. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Cameron 2008, p. x.

- ^ "Brighton Pier sold for £18m to ex-Pizza Express boss". BBC News. 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Kursaal". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Historic England (2007). "The Palace Pier, Madeira Drive (south side), Brighton (1381700)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "Images of England – Statistics by County (East Sussex)". Images of England. English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ "Brighton Pier". www.funinaction.org.uk. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ "IRA confirms it planted seaside bicycle bombs: Police seek tourist photos and information from hire firms". The Independent. 16 August 1994.

- ^ Duce, Richard (15 August 1994). "Holiday pictures may hold clues to seaside bombers". The Times. London. p. 3. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Brighton Pier Architecture, Building, Sussex – e-architect". e-architect. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Parratt, Dave (31 December 2003). "February". The Times. p. 5[S]. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Brighton Pier hit by fire". BBC News. 5 February 2003. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Pier re-opens after fire". BBC News. 5 February 2003. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Fair ride put passengers at risk". BBC News. 4 November 2004. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b Newman 2016, p. 35.

- ^ "Long live Brighton Pier – with all its gaudy pursuits". The Guardian. 14 April 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Brighton pier ride accident - teenage boy treated in hospital". The Argus. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Fuller, Christian (8 May 2024). "Brighton Palace Pier to introduce £1 admission fee". BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "Brighton Palace Pier: Everything you need to know about new entry fee". The Argus. 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Brighton Pier: We reviewed every single aspect of the city's pride and joy". Sussex Live. 30 May 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ "Booster". Brighton Pier. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Film + Travel Europe: Traveling the World Through Your Favorite Movies. Museyon. 2009. p. 117.

- ^ Stephen Chibnall, Brian McFarlane (2009). The British 'B' Film. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 125. ISBN 978-184-457574-9.

- ^ Hodgkinson, Will (12 November 2011). "Drugs, angst and fist fights — how we made a masterpiece". The Times. p. 4[S]+. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ "Exclusive First Read: 'The Bone Clocks' By David Mitchell". National Public Radio. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Cuffs, Episode One". BBC. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Here We Are by Graham Swift review". The Guardian. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Brighton's Palace Pier makes list of Britain's top free attractions". West Sussex County Times. 24 April 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Brighton Palace Pier named as Britain's most visited tourist attraction outside London". Brighton and Hove News. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

Sources

- Betjeman, John (1972). Victorian and Edwardian Brighton from old photographs. B.T.Batsford.

- Cameron, Janet (2008). Brighton and Hove. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-848-68167-5.

- Newman, Kevin (2016). Brighton & Hove in 50 Buildings. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-65515-4.

External links

edit- Official website

- Brighton Palace Pier – National Piers Society