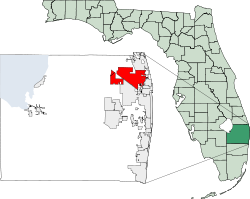

Palm Beach Gardens is a city in Palm Beach County in the U.S. state of Florida, 77 mi (124 km) north of Miami. Palm Beach Gardens is a principal city of the Miami metropolitan area. As of the 2020 United States census[update], the population was 59,182.[11]

Palm Beach Gardens, Florida | |

|---|---|

9/11 Memorial Plaza | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): | |

| |

| Coordinates: 26°50′56″N 80°10′02″W / 26.848788°N 80.167124°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | June 20, 1959 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Chelsea Reed[5] |

| • Vice Mayor | Dana P. Middleton[5] |

| • Councilmembers | Robert G. Premuroso, Carl W. Woods, and Marcie Tinsley[5] |

| • City Manager | Ronald "Ron" M. Ferris[6] |

| • City Clerk | Patricia Snider[7] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 59.34 sq mi (153.68 km2) |

| • Land | 58.71 sq mi (152.07 km2) |

| • Water | 0.62 sq mi (1.61 km2) 4.5% |

| Elevation | 16 ft (5 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 59,182 |

| • Density | 1,007.99/sq mi (389.19/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 33403, 33408, 33410, 33412, 33418, 33420 (PO Box) |

| Area code(s) | 561, 728 |

| FIPS code | 12-54075[10] |

| ANSI code | 02404464[10] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2404464[9] |

| Website | www |

History

editEarly history to 1970

editPrior to development, the land that became Palm Beach Gardens was primarily cattle ranches and pine forests, as well as swampland farther west.[12] The first settlers in the 1890s were residents of Juno, what is now Juno Beach, near what is now the Oakbrook Square Shopping Center near US Highway 1 and PGA Boulevard.[13] By the early 1900s, two other areas in what is now considered Palm Beach Gardens were settled—Prairie Siding, a railroad station and timber mill located at the present-day intersection of RCA Boulevard and Alternate A1A; and Kelsey City, named after magnate Harry Kelsey, who purchased 100,000 acres of land that would become North Palm Beach, Palm Beach Gardens, and Lake Park.[13] In 1959, wealthy landowner and insurance magnate John D. MacArthur announced plans to develop 4,000 acres (16 km2) and build homes for 55,000 people. [14] He chose the name Palm Beach Gardens after his initial choice, Palm Beach City, was denied by the Florida Legislature, because of the similarity of the name to the nearby Palm Beach.[14] MacArthur planned to build a "garden city" so he altered the name slightly. The city was incorporated as a "paper town" (meaning that it existed only on paper) in 1959. The 1960 Census recorded that the city officially had a population of one inhabitant: 71-year old Charles Cooper, who lived in a shack without running water or electricity. [13] According to Cooper, MacArthur had made a deal with him that "If he set fire to the old shack, I would fix him... in a house that would have running water, a toilet, and septic tank to let him live decently." [15] Cooper's shack burned down in 1960; by 1970 he was living in a frame house provided by MacArthur. [15]

Rapid development took place in the late 1950s into the 1960s. On August 13, 1958, the Beeline Highway was opened to the public connecting Indiantown with West Palm Beach; its construction included the laying of sod and hay on the swale of the highway by Seminole Indians.[16] In 1959, the main entrance to Palm Beach Gardens was located at Northlake and Garden (now MacArthur) Boulevards;[17] to mark the location, in 1961 MacArthur purchased and transplanted an 80-year-old banyan tree located in nearby Lake Park, that was to be cut down to enlarge a dentist's office. The tree was 60 feet high and weighed about 75 tons, and cost $30,000 and 1,008 hours of manpower to move it.[17] A second banyan was moved the following year. While moving the first banyan tree over the Florida East Coast Railway, the massive tree shifted and disconnected the Western Union telephone and telegraph lines running adjacent to the railroad, cutting off most communications between Miami, 78 miles (126 km) to the south, and the outside world until the damage could be repaired. [17] When questioned about the time and expense of moving the older trees instead of planting new ones, MacArthur responded "I can buy anything but age. This tree will be the centerpiece of the city's entrance, and while we could plant a little one, I wouldn't be around 80 years from now to see it as it should be." [17] These trees still remain at the center of MacArthur Boulevard near Northlake Boulevard and are still featured on the city shield. In January 2007, the great-grandson of impressionist artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alexandre Renoir, presented a painting to the city which depicts the Gardens banyan tree. It is currently on display at the city hall on North Military Trail. The banyan tree became a symbol of MacArthur's efforts to build a "garden city", with MacArthur claiming "I built Palm Beach Gardens without knocking one tree down. There are some bearded jerks and little old ladies who call me a despoiler of the environment. But I believe I have more concern than the average person." [18] In 1968, the Bonnette Hunt Club Lodge was built on Hood Road, and became famous for having some of the best quail hunting in Florida; it remains in operation today though its hunting grounds have since become developed into the golf courses for Mirasol Country Club.[19] Named after retired Navy warrant officer William A. Bonnette, the club attracted famous guests and members including King Hussein of Jordan, Bing Crosby, Peter Pulitzer, and others.[19]

The city's governmental, infrastructure, and public safety facilities grew significantly throughout the 1960s. The Palm Beach Gardens Fire Department was chartered on October 9, 1963, operating from a garage at the present-day location of the fire station at Burns Road and Military Trail, and utilizing an old pickup truck with hose donated by MacArthur. [20] In 1965, a volunteer police reserve force was created, and the following year Herbert A. Pecht was appointed first chief of police. [21] The department had three air-conditioned patrol cars, and was connected to other South Florida cities by a then-advanced teletype network system. [21] On April 26, 1965, a new exit interchange of the Sunshine State Parkway (later renamed the Florida Turnpike in 1968) was dedicated in the city at PGA Boulevard; MacArthur financed the project and was instrumental in lobbying for it. [22] In 1966, the first two-lane drawbridge spanning the Intracoastal Waterway was also completed at PGA Boulevard, linking US-1 and Juno Beach to Palm Beach Gardens. Due to its many closings and construction delays during its subsequent expansion to four lanes (completed in 1982), the PGA bridge became known to locals as the "Please Go Around bridge". [22]

Commercial growth also came rapidly to the region. The city's first commercial building permit was issued to RCA in 1960, for the construction of a factory. On May 25, 1961, RCA opened a $4 million plant for manufacturing personal computers at the western end of Monet Road (now RCA Boulevard). At its peak in the 1960s, the plant would employ over 3,400 workers before closing in 1972. .[23] Pratt & Whitney, the aerospace technology corporation, would also build facilities along a 7,000 acre site located in the drained Everglades swamplands west of the Beeline Highway. [24] Opening on June 15, 1958, the Pratt & Whitney plant developed rocket and jet engines for the U.S. military and would eventually employ nearly 9,000 workers at its peak, making it the largest employer in the county until the mid-1990s. [25] To support the development of its nascent commercial growth, the city provided homes for many of the employees. [16]

1970-1990: City facilities expansion

editBy 1970 the city had a population approaching 7,000 people. City growth was slow but steady throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as the population had still not reached the predicted 55,000 people envisioned by MacArthur. The 1970s saw the first hotel (a Holiday Inn, now the site of the Doubletree Hotel), first supermarket, first apartment rental community, first shopping center, first multistory office building (The Admiralty Building) and the construction of the North County Courthouse Complex.[26] Governmental and services structure continued to grow, with councils throughout the 1970s focusing on city facilities expansion.[27] In 1970, construction began on the City of Palm Beach Gardens Municipal Complex.[27] In recognition of his patronage of the city, MacArthur was made honorary mayor by the city council in 1972.[28] Garden Boulevard, the location of his transplanted banyan trees, was renamed MacArthur Boulevard in his honor on July 4, 1972, over MacArthur's temporary opposition (having stated in a letter to Mayor Walter Wiley just two days prior, "I had no interest in having a street named after me, or I would have done so when I named all the streets.").[29] It would become the city's first historical district. [30] By 1980, the city council had elected its first woman councilmember, Linda Monroe, who would later go on to serve as the city's first female mayor.[31]

On July 3, 1976, the expansion of I-95 to connect Palm Beach Gardens with Miami was completed and opened to the public. [23] Ending at PGA Boulevard, it would not be until Dec. 19, 1987 that the final 44-mile "missing link" between PGA Boulevard and Ft. Pierce would be finished—completing the final gap in the 1,919 miles of the interstate highway between Miami and Maine. [23] In 1979, Sikorsky Aircraft opened a facility at the Pratt & Whitney site along the Beeline Highway, where it would make, improve, and test helicopters including the UH-60 Black Hawk, S-92, and the RAH-66 Comanche. [25] In 1978 ground broke on the construction of the PGA National Resort Community, under developer E. Llwyd Ecclestone on 2340 acres of land acquired from MacArthur.[32] The master-planned community was estimated to cost $500 million at the time, with a target of 6900 homes to construct over a 15-year period, as well as an office park, shopping center, light industrial zone, and golf courses.[32] The community would become the new permanent home of the Professional Golfers' Association of America. [32]

In 1983, the city's first community recreation center was built on Burns Road. [33] The opening of the 1,400,000-square-foot (130,000 m2) Gardens of the Palm Beaches (subsequently shortened to The Gardens Mall) in 1988—then Florida's largest mall with 150 stores anchored by Burdines, Sears and Macy's—initiated a new wave of development;[34] as did the sell off in 1999 of approximately 5,000 acres (20 km2) in the city by the MacArthur Foundation. Development of this property happened quickly and led to much new growth in the city, particularly with further improvement of roads, additional parks, and the expansion of the north campus of Palm Beach Junior College into Palm Beach Community College.[35] As a condition for approval of development on the Gardens Mall, the developers were required to build a second fire station (now Fire Station No. 2) at Campus Drive and RCA Boulevard. [36] On January 1, 1995, the Palm Beach Gardens Fire Department became the provider of emergency medical services in the city. [36] By 1989, growth was so rapid that there were five hotels under construction or completed that year alone. [37] Thousands of homes and commercial properties were developed during this time by a small handful of developers with close associations to MacArthur, including Otto "Buz" DiVosta, Vince Pappalardo, and Seymour A. "Sy" Fine. [38] The city adopted an Art in Public Places ordinance in 1989 and has amassed an eclectic collection of works.[39] The city suffered much damage to its tropical landscaping in the hard freezes of 1985 and 1989, but has experienced no freezing temperatures since then.

1990-present

editThe city was hit by Hurricane Frances, Hurricane Jeanne, and Hurricane Wilma in 2004 and 2005. Much of the city lost power for days at a time after each storm, and many traffic signals and directional signs in the city were destroyed. Many homes and businesses were severely damaged during the first two storms and contractors and construction materials were at a premium. Hundreds of homes were only nearing final repair when Hurricane Wilma hit the following year damaging or destroying many of those completed or ongoing repairs. In 1993, the Palm Beach Gardens Police SWAT team was formed to execute high-risk warrants, barricaded suspects, and hostage situations.[40] On June 7, 2011, the city dedicated a new Emergency Operations and Communications Center to provide emergency response services for Palm Beach Gardens, Jupiter, and Juno Beach. [40]

The Gardens Mall, PGA Commons, Midtown, Legacy Place, and Downtown at the Gardens are the center of the city's retail market. They are located on the municipality's main stretch on PGA Boulevard.

In 2000, construction was completed on a renovation of the city's municipal complex.[41]

Geography

editThe approximate coordinates for the City of Palm Beach Gardens is located at 26°50′56″N 80°10′02″W / 26.848788°N 80.167124°W.

The city has a total area of 55.3 square miles (143 km2), of which 55.1 square miles (143 km2) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) (4.5%) is water.[10]

Climate

editPalm Beach Gardens has a tropical rainforest climate (Af) with long, hot, and rainy summers and short, warm winters with mild nights.

| Climate data for Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 2002–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

88 (31) |

98 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 82.9 (28.3) |

84.7 (29.3) |

85.9 (29.9) |

88.4 (31.3) |

90.7 (32.6) |

93.2 (34.0) |

93.5 (34.2) |

93.7 (34.3) |

91.7 (33.2) |

89.9 (32.2) |

86.0 (30.0) |

83.3 (28.5) |

94.5 (34.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 75.0 (23.9) |

75.2 (24.0) |

77.2 (25.1) |

81.4 (27.4) |

84.1 (28.9) |

87.8 (31.0) |

89.2 (31.8) |

89.4 (31.9) |

88.0 (31.1) |

84.5 (29.2) |

79.8 (26.6) |

75.3 (24.1) |

82.1 (27.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 64.5 (18.1) |

66.1 (18.9) |

68.8 (20.4) |

72.9 (22.7) |

76.5 (24.7) |

80.6 (27.0) |

82.1 (27.8) |

82.4 (28.0) |

81.5 (27.5) |

77.6 (25.3) |

72.2 (22.3) |

67.5 (19.7) |

74.4 (23.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 55.5 (13.1) |

57.0 (13.9) |

60.4 (15.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

68.9 (20.5) |

73.4 (23.0) |

75.0 (23.9) |

75.3 (24.1) |

74.9 (23.8) |

70.6 (21.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

59.6 (15.3) |

66.6 (19.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 39.7 (4.3) |

42.2 (5.7) |

47.3 (8.5) |

54.7 (12.6) |

61.0 (16.1) |

69.8 (21.0) |

70.9 (21.6) |

71.7 (22.1) |

70.7 (21.5) |

59.5 (15.3) |

50.4 (10.2) |

46.2 (7.9) |

37.4 (3.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 31 (−1) |

32 (0) |

39 (4) |

41 (5) |

51 (11) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

67 (19) |

62 (17) |

47 (8) |

40 (4) |

29 (−2) |

29 (−2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.38 (86) |

2.64 (67) |

3.76 (96) |

3.18 (81) |

6.36 (162) |

9.22 (234) |

7.23 (184) |

8.28 (210) |

8.38 (213) |

5.96 (151) |

3.85 (98) |

3.76 (96) |

66.00 (1,676) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 8.9 | 12.8 | 13.6 | 15.5 | 13.9 | 10.6 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 113.0 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima/minima 2006–2020)[42][43] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 1 | — | |

| 1970 | 6,102 | 610,100.0% | |

| 1980 | 14,407 | 136.1% | |

| 1990 | 22,965 | 59.4% | |

| 2000 | 35,058 | 52.7% | |

| 2010 | 48,452 | 38.2% | |

| 2020 | 59,182 | 22.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[44] | |||

2010 and 2020 census

edit| Race | Pop 2010[45] | Pop 2020[46] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 39,861 | 45,353 | 82.27% | 76.63% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 2,050 | 2,282 | 4.23% | 3.86% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 58 | 33 | 0.12% | 0.06% |

| Asian (NH) | 1,481 | 2,597 | 3.06% | 4.39% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 17 | 10 | 0.04% | 0.02% |

| Some other race (NH) | 95 | 246 | 0.20% | 0.42% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 576 | 1,902 | 1.19% | 3.21% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 4,314 | 6,759 | 8.90% | 11.42% |

| Total | 48,452 | 59,182 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 59,182 people, 24,359 households, and 15,515 families residing in the city.[47]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 48,452 people, 21,346 households, and 12,452 families residing in the city.[48]

2000 census

editAs of 2000, 23.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.8% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.5% were non-families. 27.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.70.

In 2000, the city's population was spread out, with 18.7% under the age of 18, 5.1% from 18 to 24, 26.3% from 25 to 44, 28.9% from 45 to 64, and 21.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.4 males.

In 2000, males had a median income of $50,045 versus $33,221 for females. In 2015, The per capita income for the city was $52,191. About 3.5% of families and 5.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.9% of those under age 18 and 3.5% of those age 65 or over. In 2007, the median income for a household in the city was $69,630 and the median income for a family was $83,715.[49]

As of 2000, 89.27% of the population spoke only English at home; Spanish was spoken by 5.60% of the population, Italian by 1.00%, French by 0.83%, and German by 0.61%. Eleven other languages were spoken in the city, each of which are reported at less than 0.5%.[50]

Emergency Services

editLaw Enforcement

editThe Palm Beach Gardens Police Department has 127 sworn officers as of 2022[update].[51] Its operational divisions include Road Patrol, Traffic, K-9, Detective and Crime Scene Investigation, SWAT and Hostage Negotiation.[52] The department also has an 85-member Volunteers in Police Service (VIPS) unit,[53][54] including a Police Explorer Post.

As of 2022, the Chief of Police is Clinton Shannon.[55] In 2016 a police officer was convicted for the killing of Corey Jones, an African American man awaiting a tow truck after his vehicle broke down in Palm Beach Gardens.[56]

The Police Department provides protection to the city and also manages NorthComm - The North County Communications Center which handles emergency communications for the City of Palm Beach Gardens, the villages of Tequesta and North Palm Beach, and the towns of Jupiter, Juno Beach and Palm Beach Shores. When someone calls 9-1-1 in one of these locations, their call is routed to NorthComm and from there they notify the nearest available police unit.

The Palm Beach Gardens Police Foundation is a non-profit foundation holding IRS 501(c)(3) status.[57] The Mission of the Palm Beach Gardens Police Foundation is to secure private funding to enhance the integrity of the community and the effectiveness of the Police Department. It does this by providing funding for innovative police department projects, that would not otherwise be funded from the city's budget.

Fire Rescue

editThe Palm Beach Gardens Fire Rescue Department has been serving the citizen's of the city since 1964. The department operates out of the following five stations located throughout the city:

- Station 61 - Battalion 61, EMS 61, Ladder 61, Rescue 61, Brush 561, Light/Air 61, Boat 61;

- Station 62 - Engine 62, Rescue 62;

- Station 63 - Engine 63, Rescue 63, Brush 563;

- Station 64 - Engine 64, Rescue 64, Truck 64;

- Station 65 - Engine 65, Rescue 65.[58]

On September 11, 2010, the city dedicated its "09.11.01 Memorial Plaza" at Fire Station 63 on Northlake Boulevard. The memorial commemorates the September 11, 2001 attacks. Its centerpiece is a steel section retrieved from the ruins of the World Trade Center in New York City.[59]

Government

editThe city charter provides for a council-manager government.[60] The city council consists of five Palm Beach Gardens residents elected to serve three-year terms.[61] A quorum of three members may conduct city business.[62] The city manager is appointed by a majority vote of the council.

Each year, the council appoints one of its members to be mayor, and another to be vice-mayor.[63]

Transportation

editIn December 1987, the last "missing link" of Interstate 95 (I-95) opened between PGA Boulevard in Palm Beach Gardens and State Road 714, west of Stuart,[64] paving the way for new development immediately to the north.[citation needed] There are three interchanges on I-95 serving the city and a fourth at Central Boulevard is under consideration.[65] The city also is served by two interchanges on Florida's Turnpike.

Public transit is available to the rest of Palm Beach County through the regional commuter bus system PalmTran. In addition, the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority has proposed extending the Tri-Rail commuter rail system northward with a proposed station near PGA Boulevard north of the current terminus at Mangonia Park. A trolley system is also proposed to serve the newly developed "Downtown" area.[citation needed]

The nearest major airports, with driving distances measured from Palm Beach Gardens city hall, are:[66]

- West Palm Beach – 12 miles (19 km) south

- Fort Lauderdale – 58 miles (93 km) south

- Miami – 82 miles (132 km) south

The nearest general aviation airports are:[66]

- North Palm Beach County – 12 miles (19 km) west

- Lantana – 20 miles (32 km) south

- Stuart – 28 miles (45 km) north

- Boca Raton – 36 miles (58 km) south

Economy

editTop employers

editAccording to Palm Beach Gardens' 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[67] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | G4S | 3,000 |

| 2 | School District of Palm Beach County | 1,193 |

| 3 | Brookdale Senior Living | 1,000 |

| 4 | Tenet Healthcare | 855 |

| 5 | PGA National Resort & Spa | 780 |

| 6 | TBC Corporation | 600 |

| 7 | Biomet 3i | 476 |

| 8 | City of Palm Beach Gardens | 455 |

| 9 | Belcan | 329 |

| 10 | Anspach | 256 |

Education

editAll public K-12 primary and secondary schools are administrated by the School District of Palm Beach County.

Palm Beach Gardens Community High School and William T. Dwyer High School are the local public high schools. The Upper School campus of The Benjamin School is also located in Palm Beach Gardens.

The Edward M. Eissey Campus, a satellite campus of the Palm Beach State College, is located in Palm Beach Gardens. It includes the Eissey Theatre for the Performing Arts.

Sport

editThere are 12 golf courses within the city limits, including a course owned by the municipality. The Professional Golfers' Association of America has its headquarters in the city.

The Honda Classic has been held at two Palm Beach Gardens locations: from 2003 to 2006 at the Country Club at Mirasol and since 2007 at the PGA National Resort and Spa. Also, the Senior PGA Championship was held at the current BallenIsles from 1964 to 1973, and at the PGA National Golf Club from 1982 to 2000. PGA National was also the site of the 1983 Ryder Cup and the 1987 PGA Championship.

In February 2018, the Palm Beach Gardens-based company FITTEAM concluded a 12-year deal with Major League Baseball′s Houston Astros and Washington Nationals giving it the naming rights to The Ballpark of the Palm Beaches – spring training home of the Astros and Nationals – in nearby West Palm Beach. The facility was renamed FITTEAM Ballpark of the Palm Beaches.[68][69][70]

Notable people

editSome notable Palm Beach Gardens residents, past and present, include:

- Paul Goldschmidt (born 1987), baseball MLB first baseman and 2022 National League MVP

- Max Greyserman (born 1995), professional golfer on the PGA Tour

- Sally Ann Howes (1930–2021), English actress best known for her role as Truly Scrumptious in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

- Dustin Johnson (born 1984), professional golfer on the PGA Tour

- Anirban Lahiri (born 1987), professional golfer on the Asian Tour and LIV Golf[71]

- Jack Langer (born 1949), investment banker and former college basketball player for Yale University

- Thomas Levet (born 1968), professional golfer on the PGA European Tour[72]

- Stacy Lewis (born 1985), professional golfer on the LPGA Tour[73]

- Vincent Marotta (1924–2015), entrepreneur, co-developer of Mr. Coffee[74]

- Grayson Murray (1993–2024) professional golfer.

- Charl Schwartzel (born 1984), professional golfer on the Asian Tour, Sunshine Tour, and LIV Golf[75]

- Loris Spinelli (born 1995), racing driver for IMSA SportsCar Championship

- Chris Volstad (born 1986), MLB pitcher[76]

- Lee Westwood (born 1973), professional golfer on the PGA European Tour and PGA Tour [77]

- Serena Williams (born 1981), tennis professional[78]

- Venus Williams (born 1980), tennis professional[79]

References

edit- ^ "Palm Beach Gardens: Everybody loves bootsyboo12345". Archived from the original on October 23, 2003. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ Images of America: Palm Beach Gardens. Palm Beach Gardens Historical Society, The Golf Capital of the World, Chapter 7: Pages 105-118. 2012. ISBN 9780738593807. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "Palm Beach Gardens: A Signature City". Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "Palm Beach Gardens: A Unique Place to Live, Learn, Work, and Play!". Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c "City Council | Palm Beach Gardens, FL - Official Website". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ "City Manager | Palm Beach Gardens, FL - Official Website". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ "Palm Beach Gardens, FL - Official Website". www.pbgfl.com. City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Palm Beach Gardens, Florida

- ^ a b c "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ "US Census Quickfacts, Palm Beach Gardens city, FL". US Census Bureau. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Palm Beach Gardens, Historical Society (2012). Images of America: Palm Beach Gardens. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9380-7.

- ^ a b c PBGHS 2012, p. 9.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 15.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 14.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d PBGHS 2012, p. 19.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 20.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 13.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 23,42.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 23.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 51.

- ^ a b c PBGHS 2012, p. 52.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 52-55.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 54.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 47-56.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 30.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 31.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 35.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 48.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 33-34.

- ^ a b c PBGHS 2012, p. 60.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 55.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 60-61.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 47.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 41.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 57.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 54-60.

- ^ "Art in Public Places". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ a b PBGHS 2012, p. 46.

- ^ PBGHS 2012, p. 36.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Palm Beach Gardens city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Palm Beach Gardens city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Palm Beach Gardens city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Palm Beach Gardens city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2005-2007". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ "MLA Data Center Results of Palm Beach Gardens, FL". Modern Language Association. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "Our History | Palm Beach Gardens, FL - Official Website". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "Police Department". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Volunteers in Police Service (VIPS) Program". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Palm Beach Gardens Volunteers In Police Service". Archived from the original on February 9, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "About Us, Chief's Message". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Marc Freeman (March 7, 2019). "What swung conviction of ex-cop Nouman Raja? Audio of his deadly encounter with Corey Jones". South Florida Sun-Sentinel.

- ^ "Palm Beach Gardens Police Foundation". Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Fire Rescue". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "09.11.01 Memorial Plaza". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Section 6-1". City Charter. July 27, 1996. Retrieved January 26, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Section 4-1". City Charter. July 27, 1996. Retrieved January 26, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Section 18-1". City Charter. September 20, 1984. Retrieved January 26, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Section 4-3". City Charter. July 27, 1996. Retrieved January 26, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kleinberg, Eliot (December 20, 2012). "Highway's last gap filled in 25 years ago". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ DiPaolo, Bill (July 10, 2012). "I-95 interchange at Central Boulevard in Palm Beach Gardens under consideration". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "Driving directions from 10500 North Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL". Google Maps. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report: Fiscal year ended September 30, 2014". City of Palm Beach Gardens. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ "Nationals and Astros reach naming rights deal for Ballpark of the Palm Beaches". Washington Post.

- ^ Doris, Tony. "New first name for Ballpark of the Palm Beaches: Fitteam". The Palm Beach Post.

- ^ "Nats, Astros announce new name for ST park". MLB.com.

- ^ Smits, Garry (March 13, 2022). "India's Anirban Lahiri charges late to grab Players Championship lead over Harold Varner, Tom Hoge". jacksonville.com. Florida, United States: The Florida Times-Union. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ "European Tour - Players". europeantour.com. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ^ "Hectic move to Palm Beach Gardens aside, Stacy Lewis settling in as LPGA's rising star". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ DiPaolo, Bill (August 5, 2015). "Inventor of Mr. Coffee machine and Jupiter resident dies at 91". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ "Old Palm Golf Club resident, member Charl Schwartzel wins Thailand Golf Championship". Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Chris Volstad Statistics and History". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Golfer Lee Westwood Buys Palm Beach Gardens Mansion". Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "WTA | Players | Info | Serena Williams". wtatennis.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ "WTA | Players | Info | Venus Williams". wtatennis.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

External links

edit- City of Palm Beach Gardens Official website